An examination of Black Sox salary histories

This article was written by Bob Hoie

This article was published in SABR Deadball Era newsletter articles

Editor’s note: In the Spring 2012 issue of “Base Ball: A Journal of the Early Game,” noted Black Sox expert Bob Hoie used player salary data to put to rout the long-held notion that the 1919 Chicago White Sox were underpaid. As it turns out, the Sox had the second-highest player payroll in the major leagues that season. Click here to download his article, “1919 Baseball Salaries and the Mythically Underpaid Chicago White Sox” (use password “McFarland” to open PDF). The February 2013 and May 2013 issues of the SABR Deadball Era Committee’s “The Inside Game” newsletter featured Hoie’s informative analysis and commentary upon the salary history of Shoeless Joe Jackson and the other seven Black Sox players. His analysis is presented below.

SHOELESS JOE JACKSON

Joe Jackson started his major-league career inauspiciously, playing a mere five games for the Philadelphia Athletics in both the 1908 and 1909 season, batting a combined .150 (6-for-40.) In 1910, the A’s optioned him to New Orleans of the Class A Southern Association and then made Jackson pat of a late-July trade that sent him and Morrie Rath to Cleveland in exchange for Bris Lord. Jackson remained in New Orleans until the close of the SA season before making his Naps debut on September 16, 1910.

Joe Jackson started his major-league career inauspiciously, playing a mere five games for the Philadelphia Athletics in both the 1908 and 1909 season, batting a combined .150 (6-for-40.) In 1910, the A’s optioned him to New Orleans of the Class A Southern Association and then made Jackson pat of a late-July trade that sent him and Morrie Rath to Cleveland in exchange for Bris Lord. Jackson remained in New Orleans until the close of the SA season before making his Naps debut on September 16, 1910.

Jackson began his Cleveland tenure in sterling fashion. He batted .387 in 20 late-1910 season games and then joined American League batting leaders, hitting .408 in 1911 and .395 in 1912. On the morning of August 17, 1913, Jackson’s batting average for the season was .396, giving him a .400 average (rounded up from .3995006) for his first 430 games with Cleveland. No player – before or since – has ever gotten off to such a prolific start. From there, Joe tailed off slightly, batting .324 for the remainder of the season, which left him with a 1913 BA of .373. For the third straight year, Joe Jackson was named as an outfielder on the “All America” team selected by Baseball Magazine.

During Jackson’s first three seasons, it could be said that he was the equal of the best players in the game: Ty Cobb, Eddie Collins, Tris Speaker, Home Run Baker, et al. But he lagged behind them in the salary department. In 1913, Cobb’s salary was $12,000. Speaker made $7,500, Collins $6,000, and Baker $4,500. Jackson was low man at $4,000. In 1914, the others took advantage of the looming conflict with the upstart Federal League to boost their incomes. Cobb and Speaker signed two-year contracts for a handsome $15,000/season, while Collins and Baker inked three-year deals with Philadelphia that called for $8,333 and $6,667 per season, respectively. The illiterate Jackson did not fare as well. He “signed” a three-year pact with Cleveland that paid only $5,333/season. But in retrospect, the salary numbers are not that inequitable. For although he was only 26-years old, Joe Jackson’s best years were already behind him.

- Related link: 1919 American League salaries and team payrolls, by Jacob Pomrenke

In 1911, the introduction of the cork-centered baseball had inflated American League batting averages. From 1910, AL scoring increased a run per game, from 3.64 to 4.60 in 1911, while the collective league batting average jumped from .243 to .275. By 1914, however, pitchers had adapted, and AL batting and scoring norms reverted to 1910 levels: 3.65 runs/.248 BA. During the 1914 season, Joe Jackson was sidelined for nearly a month by an ankle injury, but he still finished fourth in league batting standings with a .338 BA and was once again named to Baseball Magazine’s All America team. This put him in fairly exclusive company, as only Cobb, Collins, and Walter Johnson shared the distinction of being named to the team for each of the 1911-1912-1913-1914 seasons.

Despite the honor, the 1914 season signaled the arrival of a decline in Jackson’s performance. Offensive stats were down across the board in the American League for 1914, with batting averages dropping eight points and OPS down 19 points from the previous season. The drop-off in the Jackson numbers was more dramatic. His 1914 BA was 35 percentage points under his 1913 figure, while his OPS was down a whopping 149 points. By comparison, the decline of his peers was less eye-catching. Cobb dropped 22 (BA) and 23 (OPS), while Speaker was down 25 and 48, and Baker down 18 and 84.

But it was not just Jackson’s hitting that deteriorated. His fielding was also past its prime. After averaging 30 assists per year during the 1911-1912-1913 seasons, Jackson’s assist totals dropped into the mid-teens for the rest of his career. And while his throwing arm remained strong, it was increasingly described as erratic. The metrics which consider fielding reveal an even steeper decline. From 1913 to 1914 and adjusting for differences in the amount of games played, Pete Palmer’s BFW for Jackson drops 40 percent, Bill James’ Win Shares goes down 34 percent, and the Baseball-Reference version of WAR for Jackson declines 38 percent.

It appears plain, therefore, that Joe Jackson no longer belonged in the game’s highest echelon after the 1913 season. From 1914 through 1919, he essentially became another Bobby Veach. That is hardly an aspersion, as Veach was a fine player. But he was not a great one.

Jackson started the 1915 season about the same way he finished 1914. On July 7, he was injured when a wagon swiped his automobile. No bones were broken but Jackson suffered an elbow injury that kept him out of the lineup for three weeks. For reasons that are not clear, Joe signed a two-year contract extension covering the 1917-1918 seasons on August 7, 1915. The new deal provided for a $6,000/season salary for those two years.

Four days later, Cleveland dealt Jackson to the Chicago White Sox for $31,500 and three players. There, he joined Eddie Collins, an erstwhile A’s teammate who had followed a far more lucrative path to Chicago. In the midst of the 1914 season, the hardnosed, Ivy League-educated Collins had played the Federal League card, inducing Philadelphia to replace the three-year $8,333/season deal that he had signed before the season with a five-year pact calling for $11,500 per season. Importantly, the new Collins contract also contained a provision that specified that Collins “shall not be transferred to any other club without his consent.”

At the end of the 1914 season, AL President Ban Johnson brokered a deal that sent Collins to the White Sox in exchange for $50,000. The parties were then informed that the requisite Collins consent came with a price tag. For agreeing to the transfer, Collins was given a $10,000 bonus for signing yet another contract for his baseball services, his third of the year. This latest pact boosted the Collins salary to $15,000/season for the next five years.

In the meantime, Jackson hit only .271 in 45 games for the 1915 White Sox. His performance was such a disappointment that just prior to the American League winter meeting, rumors swirled that the Sox wanted to trade Jackson to the Yankees for Fritz Maisel. Nothing came of such talk, and it may have been no more than a ploy designed to get Joe’s attention. If so, it succeeded.

In 1916, Joe Jackson returned to earlier form, batting .341 and collecting 200 base-hits for the first time in four seasons. In recognition of his fine campaign, Jackson was again selected to the Baseball Magazine All America team — the fifth and final time that he would be accorded that honor. The 1917 season, however, was a struggle. Going into September, Jackson was batting just .276. A .444 surge the rest of the way elevated his final 1917 batting average to .301, the lowest of his career.

Joe again rebounded in the early 1918 season. He was batting .364 when he left the club on May 13 to work and play baseball for the Harlan and Hollingsworth Shipbuilding Company of Wilmington, Delaware. He was registered by the company as a “necessary employee,” the designation required to exempt him from the World War I draft. A month later, pitcher Lefty Williams and backup catcher Byrd Lynn, Jackson’s best friends on the White Sox, joined him at the Harlan shipyard.

After the November 1918 Armistice, Jackson returned to his home in Savannah. The contract extension that he had signed in August 1915 had finally expired and now, for the first time in 3 1/2 years, Jackson had to negotiate a new contract. He could not have picked a worse time. In 1918, the Chicago White Sox had pulled in only $128,396.74 in revenues, leaving a sizable $51,672.12 deficit for the year. Jackson’s last full season in 1917, moreover, had yielded the poorest stats of his career. Nor had Jackson’s abandonment of the club early in 1918 endeared him to club owner Comiskey, a vocal backer of the war effort who, like many others, deemed men who had avoided military service by taking a defense plant job to be “slackers.” Comiskey also held Jackson responsible for the defection of his pals Williams and Lynn.

Thus, the best wage that Jackson could get from the White Sox for the 140-game 1919 season was a $1,000/month stipend (or $5,250 for the likely 5 1/4-month long season). But a five-line contract addendum provided that if Jackson were a Chicago team member in good standing at the close of the season, he would receive an additional $750. Thus, the Jackson contract offered the prospect of a $6,000 salary for 1919.

While his 1919 salary ended up being the same as that his August 1915 contract extension had provided for the 1917 and 1918 seasons, Jackson would now be getting the highest pay rate of his career: $1,143 per month (given the shortened 1919 playing schedule). The Sox also apparently agreed to a longstanding Jackson contract sweetener. The club would foot the bill for wife Katie Jackson’s attendance at spring training and cover her travel expenses on those occasions when she joined Joe on the road during the regular season. All in all, given the circumstances and the uncertainties of the oncoming season, Jackson had not made that bad of a deal for himself.

In 1919, Joe Jackson hit .351, with 52 extra base hits and 96 RBIs for a pennant-winning White Sox club. In February 1920, he signed a new three-year contract that called for an annual $8,000 salary. In comparison, Bobby Veach had batted .355, with 65 extra base hits and 103 RBIs in 1919. Jackson (7) had hit more homers than Veach (3) that season, but Veach had led the entire AL in hits, and posted offensive numbers superior to those of Jackson in virtually every other category except OPS and slugging, where Jackson’s stats were slightly higher. For his reward, Veach received a $1,000 raise, boosting his 1920 salary to $6,000 (or $2,000/season under Jackson).

Over a broader period, the Jackson and Veach offensive numbers also appear comparable. During the 1914 to 1919 time span, for example, Veach had posted seven “black type” numbers in total, leading the American League in hits once, doubles twice, triples once, and RBIs three times. During the same period, Jackson had been a league leader only twice, in triples and total bases for 1916. For his entire career, Jackson posted black type numbers ten times: hits (1912, 1913), doubles (1913), triples (1912, 1916, 1920), OBP (1911), slugging (1913), OPS (1913), and total bases (1916).

In 1920, Jackson had a superb season, batting .382, with a league leading 20 doubles, while posting personal bests in home runs (12) and RBIs (121). But 1920 was the only occasion in which Jackson topped the century mark in runs batted in. Veach did it six times. On the other side of the action, the two men were not equals. By any objective measurement, Veach was a better defensive player than Joe Jackson.

Over time, perceptions often change. Nowadays, Bobby Veach is a mostly-forgotten figure from the Deadball era while Shoeless Joe Jackson has become immortal – the tragic central character of Black Sox melodrama. But analysis of their respective salaries and those of contemporaries like Ty Cobb and Eddie Collins is instructive. It is, of course, easy to say that Joe Jackson should have made more money during his major-league playing career. But the notion that he was cruelly underpaid cannot withstand scrutiny of historical evidence and circumstance.

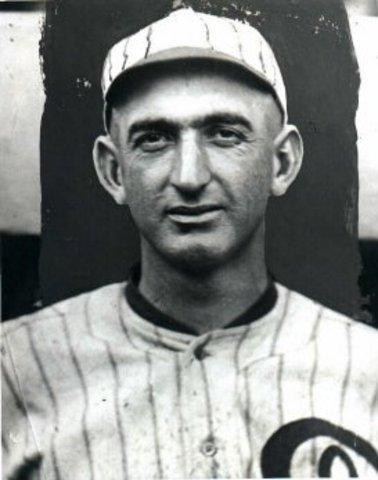

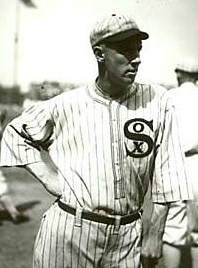

BUCK WEAVER

Buck Weaver was the third baseman on all-time All Star teams selected by Billy Evans in 1930 and Ty Cobb in 1946. But Weaver only played 427 games at third and the metrics (BFW, Win Shares, WAR) rate him not much better than an average player, and a less-than-average defensive third baseman. The metrics place him well below such contemporaries as Larry Gardner, Heinie Zimmerman, and even the New York Yankees version of Home Run Baker. And Heinie Groh is light years ahead of Weaver. Buck was never named to Baseball Magazine’s transcendent “All America” team, as that honor was always bestowed on others during Weaver’s playing career: Groh four times, Zimmerman and Baker twice each, and Gardner once. Weaver did, however, make the magazine’s American League team in 1917 and 1919. Otherwise, Baseball Magazine selected Gardner (1912-1916-1920), Baker (1913-1914-1918), or Fritz Maisel (1915) as the American League’s premier third sacker.

Buck Weaver was the third baseman on all-time All Star teams selected by Billy Evans in 1930 and Ty Cobb in 1946. But Weaver only played 427 games at third and the metrics (BFW, Win Shares, WAR) rate him not much better than an average player, and a less-than-average defensive third baseman. The metrics place him well below such contemporaries as Larry Gardner, Heinie Zimmerman, and even the New York Yankees version of Home Run Baker. And Heinie Groh is light years ahead of Weaver. Buck was never named to Baseball Magazine’s transcendent “All America” team, as that honor was always bestowed on others during Weaver’s playing career: Groh four times, Zimmerman and Baker twice each, and Gardner once. Weaver did, however, make the magazine’s American League team in 1917 and 1919. Otherwise, Baseball Magazine selected Gardner (1912-1916-1920), Baker (1913-1914-1918), or Fritz Maisel (1915) as the American League’s premier third sacker.

During Weaver’s years as a third baseman, only Baker received a higher salary than Buck – and Baker should not count. Home Run Baker may have been the greatest salary negotiator of all time, an accomplishment achieved largely through the use of mirrors. After signing a three-year contract with the Philadelphia A’s for $6,667 per year in 1914, Baker held out the entire 1915 season, demanding more money. At the end of the season, the A’s sold Baker to the Yankees for a reported $25,000. The Yankees then gave Baker a new three-year contract that paid $9,167 per season.

In his final four seasons with Philadelphia, Baker had been a Deadball Era force, averaging over 100 runs scored, over 110 RBIs, and batting in the mid-.330s. But in his first three seasons as a Yankee, Bakers offensive numbers shrank dramatically. He averaged less than 60 runs scored, a little over 60 RBIs, and hit about .280. Still, the Yankees expressed their intention to re-sign him for the 1919 season.

Magnanimously, Baker responded: “My probable return is prompted by my deep desire of duty to the owners of the New York American League Club who have expended a great deal of money for my release from the Athletics, who have not yet received due return for the investment because of tough luck in the matter of injuries to myself and other players and the bad conditions surrounding baseball in the seasons of 1917 and 1918. The consideration of money has never entered into my calculations. I feel I owe the game of baseball a great deal, for it has done me a great deal of good physically, morally and financially. It is because of my sense of duty and devotion to the game that I felt it almost obligatory on my part to return.”

As the New York Yankees had lost $46,651 in 1918 alone, and $136,994 over the 1915-1918 seasons, one might have expected Baker to announce that he was going to play for New York pro bono. Instead, Baker allowed himself to accept a $1,000 signing bonus for inking a $2,000/month contract that worked out to $11,583 over a 140-game season. Notwithstanding being on the back side of his career, Home Run Baker had managed to become the fourth highest paid player in major leagues baseball, his salary trailing only that of Ty Cobb, Eddie Collins, and Tris Speaker.

While not in Baker’s peerless class as a salary negotiator, Buck Weaver had done well for himself. He had been drafted by the White Sox from York of the Class B Tri-State League after the 1910 season, and optioned to San Francisco of the Pacific Coast League for 1911. Recalled by the Sox for the 1912 season, Weaver signed a contract for $1,800. He hit only .224, but played brilliantly at shortstop, earning a raise to $2,400. In 1913, Buck raised his batting average to .272 and continued to excel defensively.

In 1914, Weaver signed for $4,000 but his BA dropped to .246 and his defense began to decline. The following year, he signed a three-year deal at the same $4,000 per season and improved his average to .268. His defensive play, however, remained average, at best. In 1916, the Sox moved Weaver to third base and began searching for a new shortstop (first candidate Zeb Terry did not pan out). While Weaver’s BA fell to .227, the metrics suggest that he was better than average defensively during his first year as a third baseman. In 1918, Buck signed for $6,000 and hit .300, a deceptive figure as he drew few walks and had no power, generating an OPS of just .675.

In 1919, he signed a three-year contract that paid $7,250 per season. In the first year of that pact, Buck batted .296 and his power picked up. His defense, while brilliant in the eyes of many contemporary observers, was no better than average based on the numbers. In 1920, Weaver tried to renegotiate his contract, but when that failed, he went on to post career-best numbers in runs scored (102), BA (.331), slugging (.420), and OPS (.785) in his final major league season.

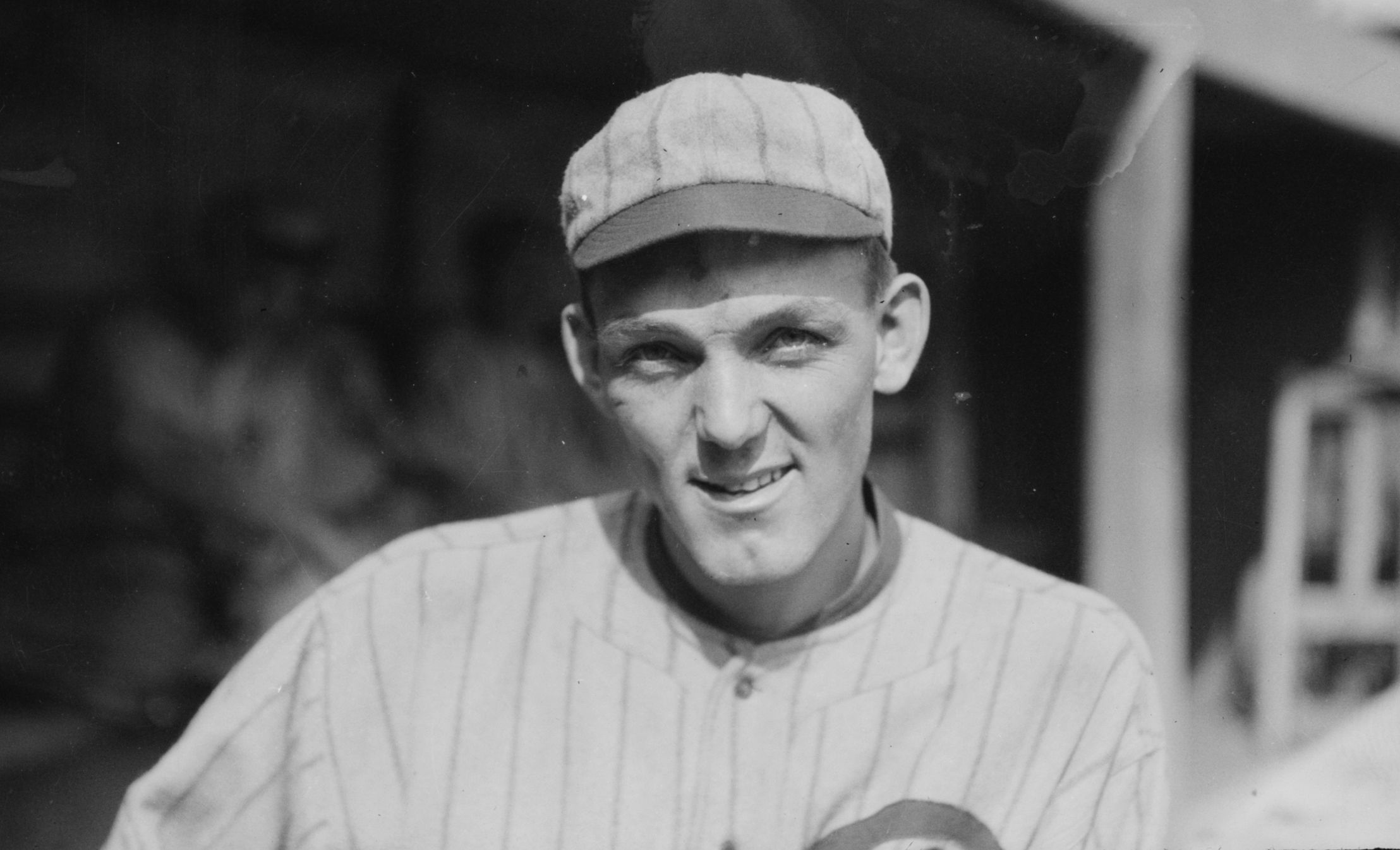

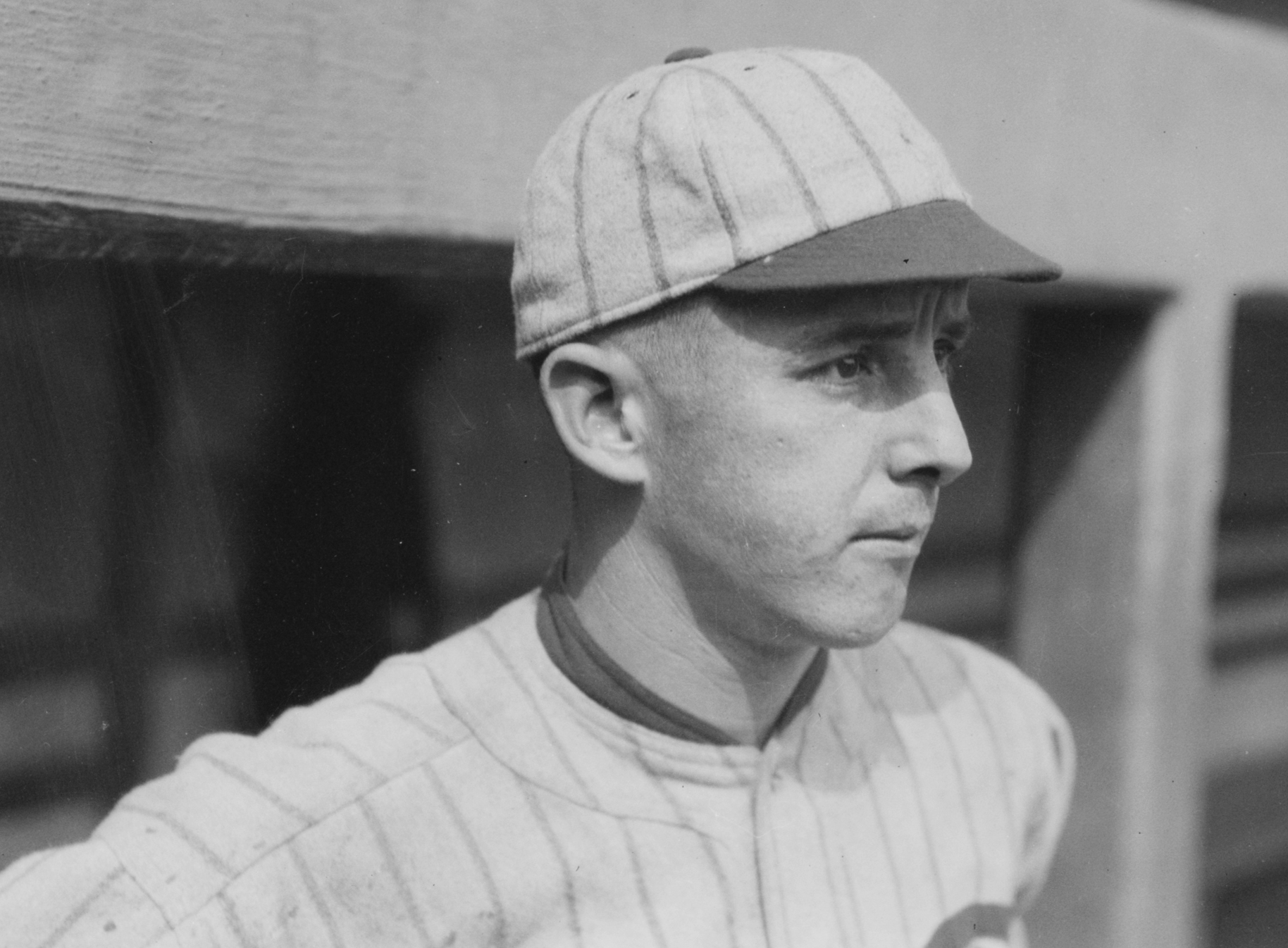

EDDIE CICOTTE

Eddie Cicotte was an anomaly. Has any other pitcher had a win sequence of 15-28-12-29 or ERA progressions of 2.04-3.02-1.75, followed by 1.53-2.77-1.82-3.26? On July 12, 1912, Cicotte came to White Sox on waivers after he had started the season 1-3, with a 5.67 ERA, for the Boston Red Sox. In his fifth full season in the majors, Cicotte had signed a $3,600 contract that year and had been a reliable middle of the rotation starter for the Red Sox.

Eddie Cicotte was an anomaly. Has any other pitcher had a win sequence of 15-28-12-29 or ERA progressions of 2.04-3.02-1.75, followed by 1.53-2.77-1.82-3.26? On July 12, 1912, Cicotte came to White Sox on waivers after he had started the season 1-3, with a 5.67 ERA, for the Boston Red Sox. In his fifth full season in the majors, Cicotte had signed a $3,600 contract that year and had been a reliable middle of the rotation starter for the Red Sox.

Once he started pitching for Chicago, Cicotte continued his losing ways, dropping his first four decisions as his combined record fell to 1-7. From there, Eddie turned it around, going 9-3 for the rest of the season to finish 10-10. For 1913, he signed another $3,600 contract and had his best season to date, going 18-11, with a 1.58 ERA. The following season, Cicotte signed for $4,250. (This amount may actually be $4,750. There is a discrepancy on the Cicotte transaction card, and given his record and the salary inflation provided by the arrival of the Federal League, I suspect that he signed for the higher figure.) After going 11-14 in 1914, Eddie signed a three-year deal that paid $5,000 per season.

In 1915, Cicotte posted a 13-12 record. He was clearly outperformed by fellow Sox hurlers Jim Scott (24-11), Red Faber (24-12), and Joe Benz (15-11). Like Cicotte, Scott was at the start of a three-year contract, but one that paid only $4,000 per season, the salary level at which he would remain for the rest of his White Sox (and major league) career. Benz had signed a three-year contract that paid $6,500 annually, while Faber had signed a one-year $6,000 pact for the 1916 season. This made Cicotte the third highest-paid pitcher on the 1916 Sox staff (with Scott fourth) regardless of win/loss record. But Cicotte earned his keep that season, going 15-7, with a sparkling 1.78 ERA, and pitching better than Benz or Faber. Faber dropped back to $4,000 in 1917 and then enlisted in the Navy. Cicotte, meanwhile, had a breakout season as a 33-year old in 1917. He went an unexpectedly great 28-12, with a 1.53 ERA, leading the AL in both wins and earned run average.

For 1918, Cicotte’s base salary remained at $5,000, but he also received a $2,000 signing bonus (which the Cicotte transaction card inaccurately labels an advance). In addition, Cicotte and the Sox had an off-contract performance-based bonus agreement. The amount of the potential bonus is not disclosed on the transaction card, but is a moot point. Cicotte did not have to worry about collecting any bonus checks as he went 12-19 and lead the AL in losses.

In 1919, Eddie’s base salary continued at $5,000. He went a superb 29-7, for which he belatedly received a $3,000 bonus (which I believe was a carryover from his 1918 off-contract agreement). He then signed for $10,000 in 1920 and posted a 21-10 mark.

In sum, the 1918-1919 Cicotte contracts and bonus payments gave him a two-year income of $15,000. The only major-league pitcher to make more money during this period was Walter Johnson at $19,000. (Grover Alexander spent most of 1918 in the US Army). Including 1920, Cicotte salaries and bonuses aggregated to $25,000, again second only to Johnson’s $31,000.

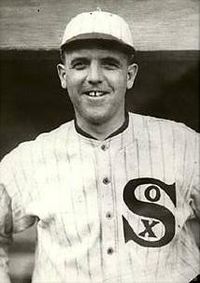

HAPPY FELSCH

Happy Felsch was acquired by the White Sox in early August 1914. His 1915 contract called for a $2,100 salary but Felsch was something of a disappointment, playing regularly in center field but batting only .248. In 1916, he got a raise to $2,700 and had a very good season, batting .307 (ninth in the AL), with seven home runs (tied for third). This performance earned Happy a three-year $3,700 per season contract with the Sox. He repaid the club with a great season, hitting .308 (fifth in the league), with 102 RBIs (tied for second) and six homers (tied for fourth). In addition, he was brilliant in the outfield. As a result, Felsch joined Ty Cobb and Tris Speaker as an outfielder on the Baseball Magazine “All America” team.

Happy Felsch was acquired by the White Sox in early August 1914. His 1915 contract called for a $2,100 salary but Felsch was something of a disappointment, playing regularly in center field but batting only .248. In 1916, he got a raise to $2,700 and had a very good season, batting .307 (ninth in the AL), with seven home runs (tied for third). This performance earned Happy a three-year $3,700 per season contract with the Sox. He repaid the club with a great season, hitting .308 (fifth in the league), with 102 RBIs (tied for second) and six homers (tied for fourth). In addition, he was brilliant in the outfield. As a result, Felsch joined Ty Cobb and Tris Speaker as an outfielder on the Baseball Magazine “All America” team.

The 1918 season was a disaster for Happy Felsch. On May 9, his BA stood at .262 after 15 games, with only three extra-base hits and five RBIs. He then left the club to visit a brother who had been seriously injured in an Army training exercise in Texas. Felsch returned to the Sox ten days later and promptly went on a batting tear, hitting .348 over his next 15 games and raising his season BA to .311. Then, the bottom began to fall out. In his final ten June games, Felsch managed only four singles in 38 at-bats, with one RBI, shrinking his BA to .252. After picking up his pay check on July 1, 1918, he left the club for his home in Milwaukee, taking a job with a local gas company and playing ball for the Milwaukee Koscioskos of the Lake Shore League. Playing Sundays and holidays, Happy hit .488 in 11 games.

Felsch never publicly explained why he left the Sox, but a December 31, 1918 column by Sam P. Hall, sports editor for the Chicago Herald Examiner, intimated that Felsch had been miffed by club failure to pay him a promised $1,100 bonus in 1917. Hall also mentioned rumors that Felsch had been angry about having his pay docked for the time that he had spent visiting his brother. The following day, Sox owner Charles A. Comiskey informed a Milwaukee Journal reporter that Felsch had been paid by the Sox for the ten days that he had been away in May 1918.

As for the bonus claim, Comiskey stated that Felsch had been “promised an additional amount if he would refrain from drinking, and although he violated this agreement, and so admitted himself, nevertheless he received the additional amount.” Comiskey then added that when Felsch left the club on July 1, “the only reason, as he is supposed to have said, was due to some trouble he had with Eddie Collins. After he left, he [Felsch] conferred with a club official and gave no reason for leaving, but promised to return and gave his word to that effect, but his word did not hold.”

On January 23, 1919, Felsch declared that he would not attempt to break his three-year contract with the White Sox. Then, for some reason perhaps having to do with his jumping the club and being placed on the suspended list, Felsch signed a new a new one-year pact on January 29, for $714.50 per month. As aggregate payment under this pact totaled $3,751.12, Happy thereby got himself a $1.12 raise. For the season, Felsch hit just .275, suggesting, at first glance, that his career was in decline from 1917. His BA was 33 points lower than his 1917 mark, but in 17 fewer games, he had hit twice as many doubles, more triples and home runs, and his OPS was nine points higher. In late February 1920, Felsch signed a $7,000 contract for the upcoming season and enjoyed his most productive year. He posted career-highs in virtually every offensive category, including homers (14, fourth in the AL), RBIs (115, sixth), and batting average (.338, ninth) in his final major league season.

CHICK GANDIL

Chick Gandil broke into the majors with the White Sox in 1910, but hit only .193. Sent back to the minors, he hit over .300 in a little more than one season with Montreal of the International League before he was acquired by the Washington Senators on May 26, 1912. Gandil signed a $500 per month contract with the club and hit .305, with 81 RBIs in 117 games, exceptional for the Deadball Era. In 1913, he got a raise to $3,600 ($600 per month) and responded by batting .318. This earned Chick a three-year contract at $4,000 per season for 1914-1915-1916. In the first year of the pact, Gandil’s average dropped to .259. But he was back up to .291 the following year.

Chick Gandil broke into the majors with the White Sox in 1910, but hit only .193. Sent back to the minors, he hit over .300 in a little more than one season with Montreal of the International League before he was acquired by the Washington Senators on May 26, 1912. Gandil signed a $500 per month contract with the club and hit .305, with 81 RBIs in 117 games, exceptional for the Deadball Era. In 1913, he got a raise to $3,600 ($600 per month) and responded by batting .318. This earned Chick a three-year contract at $4,000 per season for 1914-1915-1916. In the first year of the pact, Gandil’s average dropped to .259. But he was back up to .291 the following year.

The Senators, however, wanted to make first base available for Joe Judge, who had hit .415 in 12 late-season games for the club. So in 1916, Gandil was sold to Cleveland for $7,500. Gandil batted .259 for the Indians and then, again supplanted by another prospect (Louie Guisto, a 22-year old first baseman acquired from Portland who proved a bust), sold to the White Sox for $3,500.

By then, Gandil’s three-year contract had expired. For the 1917 season, Gandil and Chicago agreed to a new $4,000 pact. Chick hit .273, but with only 16 extra-base hits in 149 games, soft numbers for a rugged 6-foot-1 1/2-inch first baseman who doubled as a boiler man in the off-season. Yet at a banquet held in Boston to honor the pennant-winning Sox, Buck Weaver cited Gandil and Eddie Cicotte as the reasons why the Sox had prevailed.

In 1918, Gandil signed another $4,000 contract (his fifth in a row at that figure) and hit . 271. Over the ensuing winter, there were rumors that Gandil wanted to remain on the West Coast and hopefully manage a PCL team. But that seems doubtful, as Chick quickly re-signed with the Sox at $666.67 per month which, given the reduced 140-game schedule set for the 1919 season, effectively dropped his stipend to $3,500, his lowest wage since 1912.

After the 1919 season, Gandil told a reporter that he wanted to play on the West Coast if he could get his release from Sox owner Comiskey. Gandil claimed that he had been a candidate to manage Seattle but felt that rumors of a World Series fix killed his chances. As he informed vacationing Chicago sportswriter Harry Niely in January 1921, Gandil had been sent a $4,000 contract for the 1920 season by Comiskey. Gandil demanded $6,000. Comiskey countered at $5,000. But Gandil held his ground. Thereafter, Sox club secretary Harry Grabiner wrote that contract negotiations were off.

On April 24, 1920, Comiskey sent Chick a letter notifying him that he had been placed on the club’s suspended list. As it turned out, Chick Gandil’s career in Organized Baseball was now over. Two months later in an interview with sportswriter Harry Grayson, Gandil said, “I have always been an underpaid ballplayer, never got the big money but always gave my all.” In 1919, the only first basemen in the American League making more money than Chick Gandil were George Sisler, Stuffy McInnis, and Wally Pipp, and it would be difficult, if not impossible, to make the case that Chick was their superior.

LEFTY WILLIAMS

Lefty Williams had pitched briefly for the Detroit Tigers in 1913-1914, going a combined 1-4 before being sent to the Pacific Coast League. In 1915, Williams went 33-12 with Salt Lake City, leading the league in wins and strikeouts. Acquired by the Chicago White Sox, Williams signed a $3,000 contract and then went 13-7. Given a raise to $3,300 for 1917, he posted a 17-8 mark for the pennant-winning Sox, but took a cut to $3,000 for the 1918 campaign. At first appearance, this appears to make no sense. But Williams’ 1917 log was misleading. His ERA was the worst on the staff, and when possible Chicago starters for the World Series were discussed, Lefty’s name was scarcely mentioned. His 30-15 combined record for his first two seasons was likewise deceptive. His cumulative ERA was 3.28, or about 30% above the Sox staff average, and he had been the beneficiary of exceptional run support – nearly a half-run more than the Sox hurlers as a whole had received. In 1918, Williams was 6-4 when he and backup catcher Byrd Lynn jumped the club, taking a job and playing for the Harlan & Hollingsworth, the Delaware shipyard that would become his off-season place of employment for the next two years.

Lefty Williams had pitched briefly for the Detroit Tigers in 1913-1914, going a combined 1-4 before being sent to the Pacific Coast League. In 1915, Williams went 33-12 with Salt Lake City, leading the league in wins and strikeouts. Acquired by the Chicago White Sox, Williams signed a $3,000 contract and then went 13-7. Given a raise to $3,300 for 1917, he posted a 17-8 mark for the pennant-winning Sox, but took a cut to $3,000 for the 1918 campaign. At first appearance, this appears to make no sense. But Williams’ 1917 log was misleading. His ERA was the worst on the staff, and when possible Chicago starters for the World Series were discussed, Lefty’s name was scarcely mentioned. His 30-15 combined record for his first two seasons was likewise deceptive. His cumulative ERA was 3.28, or about 30% above the Sox staff average, and he had been the beneficiary of exceptional run support – nearly a half-run more than the Sox hurlers as a whole had received. In 1918, Williams was 6-4 when he and backup catcher Byrd Lynn jumped the club, taking a job and playing for the Harlan & Hollingsworth, the Delaware shipyard that would become his off-season place of employment for the next two years.

While Comiskey had made noises about never letting a defense plant jumper play for his team, Williams made a threat of his own, informing Chicago manager Kid Gleason that he would not rejoin the Sox until the club paid him the $183.16 that Williams claimed to be owed for the first 11 days of June 1918. (Williams’ claim was later considered and rejected by the National Commission.)

Eventually, Lefty re-signed with the Sox for $500 per month on January 29, 1919. This was the same pay rate as 1918, but covered only a 140-game schedule, reducing Williams’ actual 1919 pay to $2,625. The pact, however, contained a $375 bonus clause that would raise Lefty’s total salary back to the $3,000 level if he won 15 games. The parties also entered an off-contract agreement whereby Lefty would receive an additional $500 bonus if he became a 20-game winner. Thus, Williams’ 23-11 mark yielded a career-high $3,500 in 1919. Williams had pitched well that season, with his 2.64 ERA being nearly a half-run under the staff norm, but his run support remained the highest on the club.

On March 1, 1920, the soon-to-be 27-year-old Williams signed for $6,000, with an off-contract agreement calling for a $500 bonus if he won 15 games and an additional $1,000 for winning 20. Lefty earned both, going 22-14. He was suspended by Comiskey in late September before he could collect the full $7,500, but the $6,933.33 that Williams was paid was near double his previous earnings best.

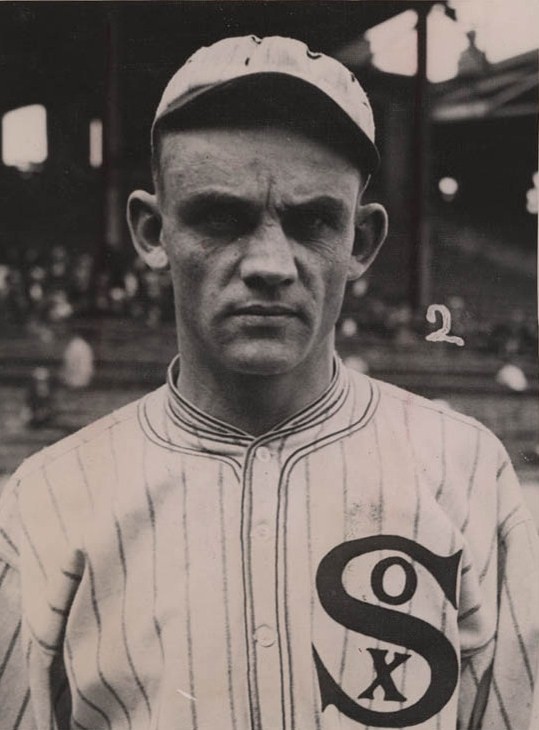

SWEDE RISBERG

Swede Risberg was only 22 years old when the White Sox acquired him from Vernon of the Pacific Coast League in 1917. But by that time, Risberg had already played five seasons in the minors. Swede immediately became the Sox starting shortstop, but hit only .203 and was benched for the 1917 World Series, with Buck Weaver assuming the position and Fred McMullin assigned to third. Risberg had a great arm but was considered a somewhat erratic fielder, and the metrics suggest that his defense was terrible in 1917. In 1918, he signed for $2,500, raised his batting average to .256, and improved his defense – although it was still below average.

Swede Risberg was only 22 years old when the White Sox acquired him from Vernon of the Pacific Coast League in 1917. But by that time, Risberg had already played five seasons in the minors. Swede immediately became the Sox starting shortstop, but hit only .203 and was benched for the 1917 World Series, with Buck Weaver assuming the position and Fred McMullin assigned to third. Risberg had a great arm but was considered a somewhat erratic fielder, and the metrics suggest that his defense was terrible in 1917. In 1918, he signed for $2,500, raised his batting average to .256, and improved his defense – although it was still below average.

In 1919, Swede signed a two-year contract for $3,250 per season. He again hit .256 but his great defense in the latter part of the season impressed Chicago sports reporters. (From a review of 1919 box scores, there was a 33-game stretch late in the season where Risberg’s range factor went up a play a game, and his errors dropped significantly. But the Risberg range factor during that time was not off the charts.)

Like Weaver, Risberg tried to hold out in the middle of a multi-year contract but he eventually reported to spring camp in 1920. For the regular season, Swede hit .266 and drove in 65 runs, which placed him third in RBIs on the Sox behind Joe Jackson and Happy Felsch, all while batting in the seventh spot for the entire season.

Longtime Yankees executive Ed Barrow selected personal all-time all star squads in 1929, 1939, and 1950. Barrow also selected an all-time best team. In 1939, Barrow selected the 1938 New York Yankees as his all-time best team. In 1929 and 1950, however, he opted for the 1919 Chicago White Sox. But here is the ultimate head scratcher, courtesy of an article entitled “Ed Barrow, Yankee President, Picks All Time Baseball Team.” In a February 19, 1939 interview with sportswriter Jimmy Powers of the Chicago Tribune-New York Daily News syndicate, Barrow declared that, “I hold no grudges. That’s why Risberg is my second choice at short [behind Honus Wagner], Black Sox scandal or not.”

FRED McMULLIN

Fred McMullin was purchased from Los Angeles of the PCL by the White Sox in 1916. He signed for $500 per month, or $3,000 per season — which was unusually high for a rookie. McMullin hit .256 as a utility man, a post that he would fill his entire Sox career, as he never played more than 70 games in a season. In 1917, he took a cut to $2,750 and hit .237. Fred signed for the same in 1918 and hit .277. In 1919, he agreed to $500/month, which was facially a raise but, with the scheduled reduced to 140 games, actually lower pay. He hit a career-high .294 and then signed for $3,600 in 1920, and proceeded to bat a career-low .197.

Fred McMullin was purchased from Los Angeles of the PCL by the White Sox in 1916. He signed for $500 per month, or $3,000 per season — which was unusually high for a rookie. McMullin hit .256 as a utility man, a post that he would fill his entire Sox career, as he never played more than 70 games in a season. In 1917, he took a cut to $2,750 and hit .237. Fred signed for the same in 1918 and hit .277. In 1919, he agreed to $500/month, which was facially a raise but, with the scheduled reduced to 140 games, actually lower pay. He hit a career-high .294 and then signed for $3,600 in 1920, and proceeded to bat a career-low .197.

McMullin was a very capable defensive third baseman, and handled that position for the Sox throughout the 1917 World Series. Because there was little drop off when Fred McMullin was in the lineup, he was one of baseball’s higher paid utility men.

BOB HOIE, a retired urban planner for Los Angeles County, is a long-recognized expert on West Coast baseball and the Black Sox Scandal. He was the Bob Davids Award winner for meritorious service to SABR and the game in 1987.