The Guide to Spalding: San Diego, 1900–15

This article was written by Mark Souder

This article was published in The National Pastime: Pacific Ghosts (San Diego, 2019)

Albert Spalding lived an extraordinary life as one of baseball’s most important figures. This article focuses on his San Diego years, during which he helped develop San Diego into the city it is today, as well as key connections in his early life that set up his grand finale.

Albert Spalding lived an extraordinary life as one of baseball’s most important figures. This article focuses on his San Diego years, during which he helped develop San Diego into the city it is today, as well as key connections in his early life that set up his grand finale.

The Rockford Files

Rockford, Illinois, is an industrial city on the Rock River, 80 miles northwest of Chicago. Nineteenth-century baseball fans know it as the home of the Rockford Forest Citys of the National Association, which had a one-year life in that organization. Albert Spalding was born in Byron, 13 miles southwest of Rockford along the Rock River, on September 2, 1850. His father died when Albert was only 8 years old. Albert had already been sent to Rockford to live with his aunt. After his father’s death, the rest of his family followed.1

Rockford established the most important connections for Spalding in business, baseball, and his personal life:

1. Albert Spalding learned to play baseball in Rockford. Spalding biographer Peter Levine notes that Spalding considered baseball “the only bright skies for me in those dark days of utter loneliness” as a child in Rockford.2 By age 15, he was playing for the local Pioneers team. His fame burst out in Chicago and nationally when his pitching for the Forest Citys led to the only defeat of the National club of Washington during their groundbreaking 1867 Western Tour.

2. Ross Barnes, one of the great overlooked legends of nineteenth-century baseball, was a boyhood neighbor and close friend of Albert’s. He was his baseball teammate in Rockford, Boston, and Chicago. While in Boston he joined with Louis Mahn to manufacture baseballs, which soon became part of the early Spalding sports empire.

3. His mother, Harriett Spalding, provided all the $800 capital to establish his brother Walter Spalding and Albert’s first sporting goods store at 118 Randolph Street in Chicago in 1876.

4. His brother-in-law William Thayer Brown of Rockford, son of a local banker, provided the capital to enabled the Spaldings to purchase their first bat factory in Hastings, Michigan. He was married to Albert’s sister Mary.3

5. Elizabeth “Lizzie” Churchill (Mayer) Spalding of Rockford, who was Albert’s first true love. They were engaged in Rockford, broke it off, both married another, had an affair that included a child, and, after the death of both of their spouses, were married in 1900. Lizzie is why Albert moved to San Diego. After breaking up with Spalding in Rockford, Elizabeth married George Mayer and settled in Fort Wayne, Indiana. She taught at the Fort Wayne Conservatory of Music. She had moved to San Diego to become director of the Isis Conservatory of Music at Lomaland in 1897.4

6. William D. Page was Elizabeth’s uncle. He became Spalding’s business representative. In 1909, he and his family moved to Point Loma from Fort Wayne, where William had been the founder of the Fort Wayne News, the postmaster in Fort Wayne, and a leader in the local Republican Party. He managed Spalding’s California Senate campaign. Along with his brother Charles, they were part of the group that formed the San Diego Securities Company in 1911, which developed the Loma Portal community.

7. Charles T. Page, William’s brother and another uncle of Lizzie’s from Rockford.

Page played on the Forest City team prior to its professionalization with Spalding and Barnes. Spalding, Barnes, and Page ate together, played together and sometimes slept in the same bed during those Rockford baseball days. Spalding often stayed at the Page home, and William and Charles referred to Spalding’s mother as “Mother Spalding.”5 Page became a successful businessman in Rockford, Chicago, and Atlanta. While in Chicago, Page purchased a block of the Cubs stock, supported by Spalding.6

Boston and Chicago

Spalding spent five years in Boston from 1871 through 1875. He and fellow Rockford native Barnes joined Harry and George Wright to make the Boston Red Stockings the dominant baseball team in America during the life of the National Association. Boston provided Spalding with the connections he needed to dominate early baseball equipment sales. He purchased the sporting goods operations of Wright & Ditson, Peck & Snyder in New York, and Al Reach in Philadelphia, as well as the patent for the Mahn baseball in Boston.

Two other important parts of Spalding’s life also had origins in Boston. Spalding married Sarah Josephine Keith, who was from a respected Boston-area family. And in the winter of 1874, Harry Wright sent Spalding to England to arrange a baseball tour there. Wright, a former star cricket player, wanted to show the Brits how to play American baseball. The Red Stockings and theAthletics of Philadelphia traveled to Liverpool, where they played the first game between American professional baseball teams outside of the United States.7 The impression of this first world tour and its purpose helped change Spalding’s worldview from provincial to international.

When the National League organized in 1876, William Hulbert lured Spalding back to Chicago with the promise of $2,000 and 25 percent of the Chicago White Stockings’ gate receipts. Spalding had also received, in 1876 with the help of Hulbert, the contract to exclusively produce the “official League book.” He also produced a supplemental publication, Spalding’s Official Baseball Guide.8 In 1887 the Sporting News claimed that his Michigan plants were producing a million baseball bats a year. Separate factories also produced equipment for other sports.9 In Chicago, Albert Spalding became a very wealthy man, baseball’s first millionaire. San Diego benefited from this great wealth.

Spalding left Chicago for Theosophical reasons. His marriage in 1899 to the widowed Elizabeth Churchill Mayer, his long-time love, at Point Loma, California, signaled that he was heading west. Lizzie Spalding was an important participant in the American Theosophical movement.

Theosophy

The word theosophy derives from theos and sophia, the Greek words for God and wisdom. Its speculative thoughts can derive from mystical insights or from an analysis of comparative religions. Many variations of such groups arose throughout the world that were frowned upon by the Catholic and Protestant churches.10

The Theosophical Society was created by Madame Blavatsky, a Russian who wanted “to make an experimental comparison between spiritualism and the magic of the ancients.” The original objectives, somewhat watered down later, were “to oppose the materialism of science and every form of dogmatic theology, especially the Christian.” The final goal was to promote “a Brotherhood of Humanity.”11

In 1884, Madame Blavatsky’s reputation was damaged by charges that she had instructed some employees in the use of trickery to simulate psychic phenomena. It led to splits and struggles for control of the movement, both in the U.S. and internationally.12 Capitalizing upon the dissent, and ultimately gaining control of the American part of the movement, was Katherine Tingley.13 Once her authority was established in 1896, she proclaimed her vision of a “white city” that “would serve as the headquarters of the Theosophical Society and a place where the theosophical way of life could be realized,” in the words of Emmett Greenwalt, author of California Utopia: Point Loma: 1897–1942.14

Needing a dramatic story to flip the Society from its New York City roots to a small city in southern California, she told of a meeting in New York with the famed explorer and politician John C. Fremont, who died in 1890. Tingley describes the revelation that came from Fremont:

I told him this story, this fairy story, that in the golden land, far away, by the blue Pacific, I thought as a child that I could fashion a city and bring the people of all countries together and have the youth taught how to live, and how to become true and strong and noble, and forceful royal warriors for humanity. “But,” I said, “all that has passed; it is a closed book, and I question if it will ever be realized.” He said: “There are some parts of your story that attract me very much. It is your description of this place where you are going to build your city. Have you ever been to California?” “No,” I answered. “Well,” he said, “the city you have described is a place that I know exists.” And he then told of Point Loma. He was the first to name the place to me.”15

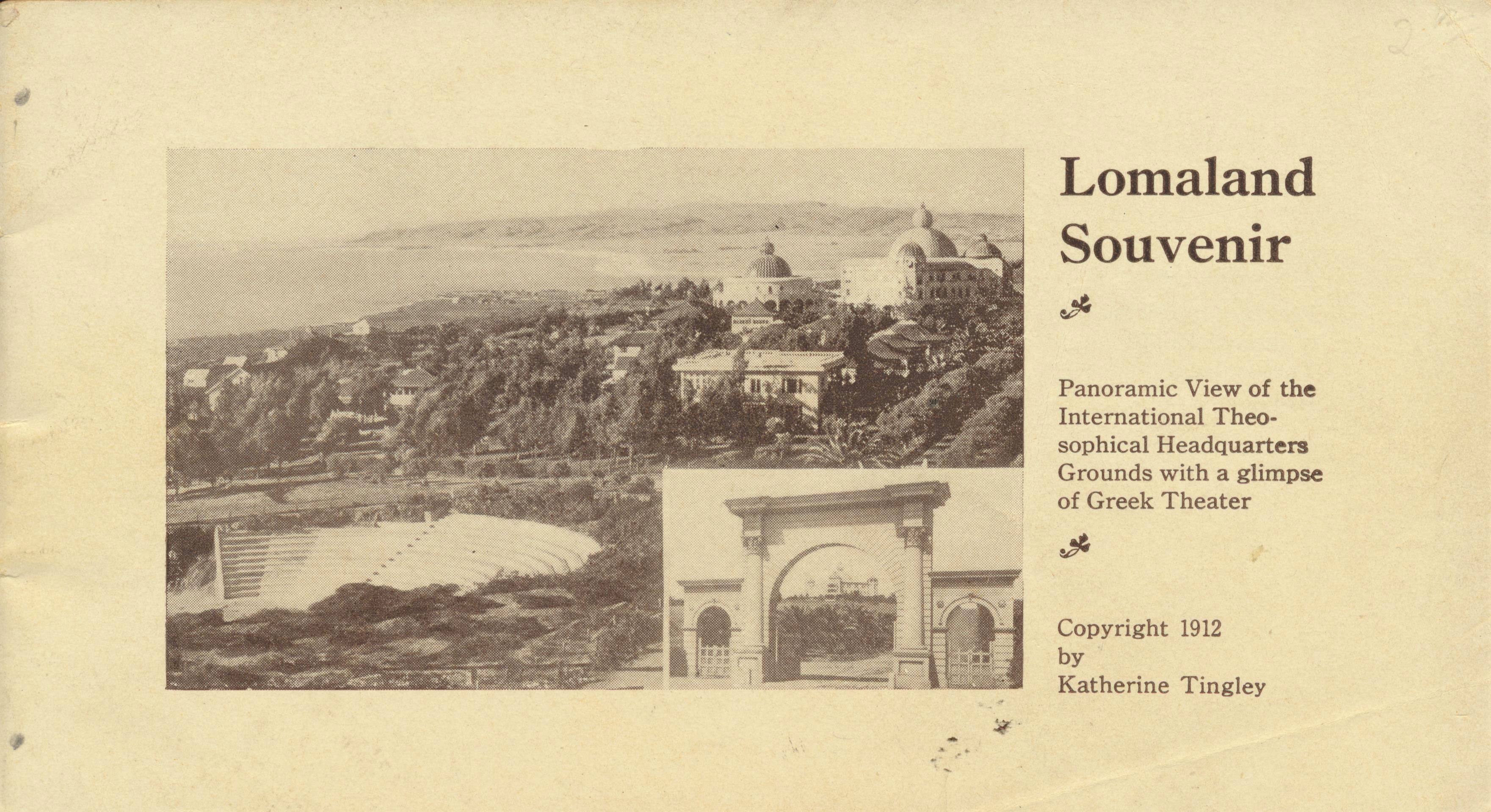

Souvenir booklet distributed by Lomaland at the Panama-California Exposition. (COURTESY OF MARK SOUDER)

Spalding Arrives at Lomaland: 1900

Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo, a conquistador, was the first European explorer to land on the West Coast of the United States in 1542. The National Park Service believes that Cabrillo landed on the east shore of Point Loma, near the current Cabrillo National Monument. After the initial Spanish landing, it was 227 years before the Spanish created a settlement in California. They had been preoccupied with establishing control in areas to the south. The missionary responsibility was eventually tasked to the Franciscans, with Father Junipero Serra in charge. After landing with the ship San Antonio in San Diego Bay, Serra established the first of the nine missions that he personally founded.16 San Diego de Alcala was dedicated on July 16, 1769. San Diego’s Pacific Coast League and major-league baseball teams were named for the Franciscan fathers.

When Albert Spalding first arrived in San Diego in 1900 it was a historic but sleepy small city. Rockford had a larger population than San Diego until 1910. The military was just beginning to establish a foothold in San Diego as it began to look increasingly toward the Pacific. The two major tourist attractions in 1900, in addition to the temperate climate and the beaches, were the Hotel del Coronado, which had opened in 1888, and Lomaland, the developing Theosophist compound on Point Loma, which was dedicated in 1897.17

Albert and his first wife, Josie, had their primary residence in Chicago but she summered along Rumson Road at Sea Bright, New Jersey, from 1890 until she died there in July 1899.18 The summer mansions of many of America’s wealthiest families made Rumson Road and the Jersey Shore among the nation’s most prestigious addresses during that period.19

In June 1900, Albert married Lizzie Mayer, his former fiancée, at his wife’s residence at Lomaland.20 Spalding clearly did not marry Mayer and move to Lomaland to receive lots of positive press clippings. A feature story in the San Francisco Examiner is an example of mocking coverage that followed him after he joined the colony. A large drawing of Spalding sitting on a horse with a sketch of his new home at Lomaland covering its body is headlined “Leaves Baseball for Mysticism” and captioned “Forsakes Baseball for Theosophy.” One of the articles underneath is titled “Spalding Becomes Theosophist by Marriage: Famous Athlete, Converted by His Wife, Has Become a Member of the Tingley School of Mystery at Point Loma.” 21

The most famous controversy regarding Lomaland was the establishment of a Raja yoga school there. Another involved allegations of child abuse. Immediately after the Spanish-American War, Catherine Tingley began sending the first Cuban children to Point Loma. In his book Baseball in the Garden of Eden, John Thorn points out that since many adults joining Lomaland were childless or elderly, Cuba “could provide a stock of orphans, as well as children whose parents wished them to be educated in America. . . . It would not be long before the majority of students at Point Loma were Cuban.”22

In 1902, a group of Cuban children was detained at Ellis Island at the request of the New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. The immigration hearing tarred the Point Loma institution and a furious Spalding was questioned about charges such as children being given only limited food and mothers being prevented from seeing their children. The New York hearing went against Lomaland. Had the ruling stood, Cuban children would have been prevented from going to the compound to be educated, and Lomaland’s reputation would have been ruined. But the decision was overturned in Washington. The state of California investigated the school and gave it positive reviews.23

Spalding, when asked his views on Theosophy, generally described it in terms of his wife’s passion and that he “married into it.” He told the San Francisco Examiner, “I find here at Point Loma many educated, cultured, refined and most genial people, certainly the equal of, and perhaps superior to, any I ever met anywhere.” He continued, “I am not, however, so ardent a Theosophist as Mrs. Spalding.” But he gave a qualified endorsement of its worldly work: “If all these things and more which I might mention, make me a theosophist, I am perfectly willing to stand for it.”24

While living on Point Loma, Spalding’s last big baseball project was the creation of a prestigious commission to rebut the argument that baseball was not a truly American original game. In 1907, it ordained Major Abner Doubleday as the inventor of baseball in Cooperstown, New York. As all baseball historians know, that is false. There is no established record that Doubleday was even interested in baseball. He was, however, a Theosophist.

In 1873, Doubleday retired from his military career and settled in New Jersey. There he became active in the Theosophical Society, becoming president of the American operations in 1878. Doubleday’s active participation in the Society could have smoothed his way to becoming the rather mystical founder of baseball in the eyes of the Spalding Commission.

Albert Spalding: San Diego Boomer

Spalding played a key role in shaping San Diego. A postcard from 1914 shows the city from a perspective just east of the developing Balboa Park, looking toward the ocean. In the distance, the entrance to San Diego Bay has mostly barren Point Loma forming the north side and on the south side is the Silver Strand, a narrow sand isthmus, and Coronado Island. On the high ground, barely visible out on the peninsula, is Lomaland, standing mostly alone, eight miles from San Diego.

Spalding played a key role in shaping San Diego. A postcard from 1914 shows the city from a perspective just east of the developing Balboa Park, looking toward the ocean. In the distance, the entrance to San Diego Bay has mostly barren Point Loma forming the north side and on the south side is the Silver Strand, a narrow sand isthmus, and Coronado Island. On the high ground, barely visible out on the peninsula, is Lomaland, standing mostly alone, eight miles from San Diego.

Lomaland was not a pejorative term given to the Theosophy campus but how it referred to itself. As noted, it was a significant tourism draw. Daily excursions to the site came from Hotel del Coronado and other hotels in the region. A souvenir booklet was created for visitors titled Lomaland Souvenir: Panoramic View of the International Theosophical Headquarters Grounds with a glimpse of Greek Theater. The booklet’s photos include the “Raja-Yoga College and Aryan Memorial Temple from the West,” as well as photos of the first Greek amphitheater built in the U.S. Nor did Lomaland hide its students, featuring photos of the children and an explanation of its educational mission. On page nine, the booklet mentions: “To the north is one of the residences, the first one erected in Lomaland, leased by Mr. A. G. Spalding.”25

Included on the 132 acres of Lomaland was Spalding’s first project, his new home. Marc Lamster, an architecture critic who wrote a book on Spalding’s world tour, described it as “an oriental fantasy, an octagonal structure with an external spiral staircase, extensive internal carvings, and a crystal on the roof.”26 The Spalding home survives as the administrative building of Point Loma Nazarene University.

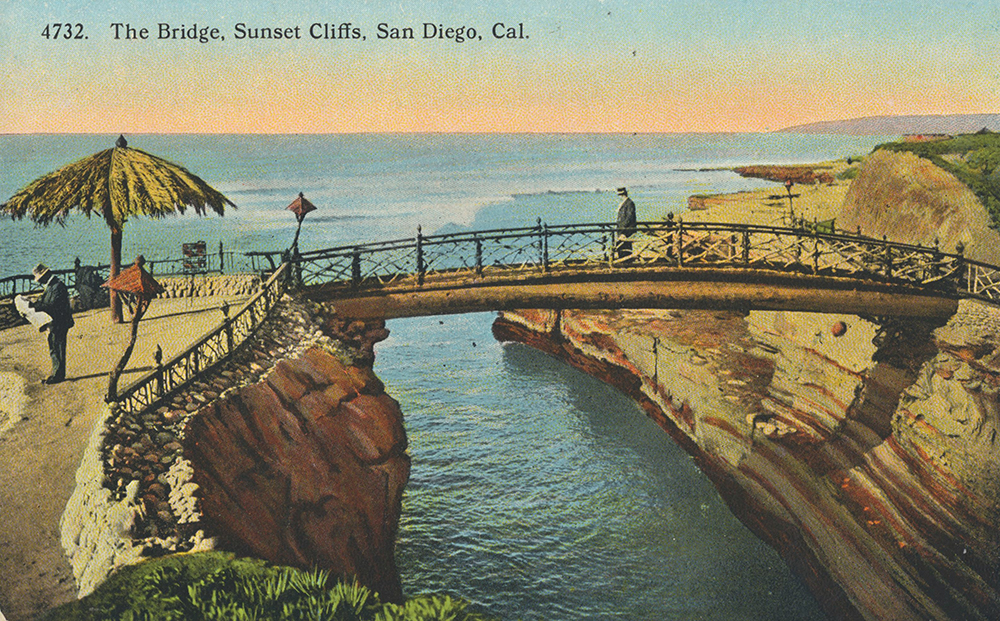

In 1903, just north of his two-story, gleaming white showplace, Spalding developed a “fanciful, cliff-side Japanese garden.”27 He spent an estimated $2 million ($55 million in today’s dollars) constructing his park.28 Most of its structures slid into the Pacific Ocean from erosion or were undermined by dangerous ocean-carved caves. The remaining structures were removed because they had accelerated cliff erosion that was naturally occurring. Spalding’s efforts did result in the area being preserved as one of the few stretches of undeveloped coast in San Diego, Sunset Cliffs Natural Park.29

In 1912, Spalding built his Point Loma Club nine-hole golf course. It was one of the first golf courses in San Diego, preceded only by those at Hotel del Coronado and within Balboa Park.30 Its dramatic elevation changes provide golfers with panoramic views of the downtown skyline and the harbor.31 Spalding built his course where Point Loma began to rise, about three miles southeast of his home. The Point Loma Golf Club merged with the San Diego Country Club in 1914. The San Diego Country Club again separated in 1921, moving to Chula Vista.32

How the Panama Canal Transformed San Diego

The Spanish-American War led to Cuba becoming a protectorate of the United States. The Philippines were also purchased from Spain. Not only did this lead to Cuban children coming to Lomaland as students, but also to the United States taking over the development of the Panama Canal in order to protect its territorial interests, promote trade, and utilize its increased naval power.

“Apart from wars, it represented the largest, most costly single effort ever before mounted anywhere on earth,” wrote historian David McCullough. “It was both the crowning constructive effort of the Victorian Era and the first grandiose and assertive show of American power at the dawn of the new century. And yet the passage of the first ship through the canal in the summer of 1914 — the first voyage through the American landmass — marked the resolution of a dream as old as the voyages of Columbus.”33

During the late nineteenth century, world’s fairs began to gather American attention beyond New York, especially after the success of the World’s Columbian Exhibition of 1893 in Chicago. Business leaders of the San Diego Chamber of Commerce sought to seize the opportunity that geography presented: San Diego Bay was the first port that ships would encounter in the United States when steaming north after traversing the Panama Canal.

In 1909, the Panama-California Exposition Company was formed to seek official designation and funding. San Diego was the smallest city ever to attempt an exposition. U. S. Grant Jr. was named president. Spalding served as a vice president along with John D. Spreckels, L. S. McClure, and G. Aubrey Davidson, the president of the San Diego Chamber of Commerce who had developed the proposal to hold an exposition.34

The effort to attract, plan, and execute the Panama-Pacific Exposition led to immediate population growth in San Diego County, from 37,000 to over 100,000 by the time the exposition opened in 1915. The wealthy business patrons had already begun building roads and rail tracks but they lacked a focal point for their efforts. The exposition gave them one. First, however, they had to fight off San Francisco’s attempt to seize the exhibition. Lyman Gage had led the rescue effort in Chicago when New York attempted to subvert Chicago’s effort to land the 1893 World’s Fair. After serving as Secretary of the Treasury from 1897 to 1902, Gage, a convert to Theosophy, built a house in La Playa, approximately 2,000 feet from his friend Spalding. He then assisted San Diego in maintaining its host designation, shared with San Francisco.

Spalding, Spreckels, and E. W. Scripps were named San Diego County road commissioners by the Board of Supervisors in 1909. Spreckels was the wealthiest man in San Diego. Anchoring his wealth was a steamship company critical to developing trade with the South Pacific, specifically sugar from Hawaii. Among other things, he owned the Hotel del Coronado and the San Diego Union. Scripps, head of the Scripps-Howard newspaper chain, owned substantial land east of La Jolla.

The three men, referred to as the “Triple S” commission, led a coordinated city effort to transform itself beyond just roads. In 1907 Spalding, Spreckels, and Scripps had responded to a request from two other San Diego leaders who came to them for significant financial assistance to purchase the 14 lots comprising Presidio Hill, the historic grounds of Father Serra’s first mission. Perhaps the baseball team would not be called the Padres had this site been lost to development.35 The Exposition coalition battled between those who wanted it to be held on the waterfront and those who wanted to develop the central city park space. The park was selected and renamed Balboa Park. The predominant style of its major structures led to the creation of an adapted Spanish Colonial, Mediterranean style that has become identified with San Diego and much of California. An example outside Balboa Park is the Santa Fe Railroad Depot in downtown San Diego, which opened in 1915 to accommodate Expo visitors. This style was a major change from the neo-classical domination of previous Fairs, including the Palace of Fine Arts in the San Francisco Panama-Pacific Exposition.

A 2,300-foot pleasure street called the Isthmus was the primary attraction for visitors at Balboa Park. Sights along the way included a 6,000-foot roller-coaster and a 250-foot replica of the Panama Canal, with ships moving up and down through locks.36 The Isthmus Zoo was such a popular attraction that during the Expo, a Zoological Society was organized. They purchased the Isthmus animals and, in 1916, opened the world-famous San Diego Zoo in Balboa Park.37

Sunset Cliffs on Point Loma, developed by Spalding, was a major visitor attraction. (COURTESY OF MARK SOUDER)

Spalding for U.S. Senate

In 1910, the business leaders of San Diego pushed Spalding to run for the United States Senate. In many ways, Spalding was a progressive, but he was opposed by the Lincoln-Roosevelt Club, which controlled the Progressive movement. The progressives chose John D. Works as their candidate for Senate partly because of his popularity in the temperance movement and his leadership of the Good Government League of Los Angeles.38 The dominant force in California politics at the time was the Southern Pacific Railroad’s Political Bureau, which the progressives were determined to defeat.39

Spalding narrowly lost the non-binding primary 64,757 to 63,182.40 The Progressive forces won the majority of the Republican nominations, including the overwhelming majority of the 428 delegates for the Republican state convention.41 However, in 1910 it was still the state legislators who selected senators. They chose Works over Spalding 92–21. Spalding supporters were irate since he had carried the majority of the counties, which theoretically would have given him a decisive 75 pledged legislators. But the primary vote was advisory, not binding.42 The progressives had swept the field, as illustrated by the convention domination. They clearly opposed Spalding.

Spalding campaign manager William Page, his wife’s uncle, was outraged. The 1911 Spalding Guide includes a three-page tirade about the “rape of a people’s direct primary law.” Page accurately points out that Works underperformed Progressive ballot leader Hiram Johnson. He also notes the double-standard of the Progressive forces’ denunciations of bossism and then offering “deals” to override the presumed preferences of primary voters. Page further proves the hostility of the Progressive leaders to Spalding by listing the extreme tactics they used to block Spalding’s nomination. It might have been a “monstrous wickedness,” or at least inside hardball, but it was legal.43

Spalding dropped out of key area positions after his loss, including the Roads Commission and the Panama-Pacific Exposition board, but he remained active. He continued developing Sunset Cliffs Park. He started his golf course near the entrance to the Loma Portal community in 1912. They both were attractions during the Exposition. He became president of San Diego Securities in 1912, a position he held until his unexpected death in 1915. It developed the Loma Portal neighborhood, which opened in 1913 in time to capitalize on the Panama Expo. The board of directors included the Page uncles as well as George Burnham, who became a vice president of the Expo after Spalding withdrew. Colonel Charlie Collier financed the trolley that came to the entrance of the area, which enabled it to attract home buyers as well as visitors for Spalding’s other Point Loma ventures.44 Collier was selected by the original Panama-Pacific board, including Spalding, to be director-general of the Expo in 1909. He chose Balboa Park as the site and oversaw the project.

In other words, while Spalding lost the Senate race, he remained active until the end of his life in helping reshape the face of San Diego.45

MARK SOUDER served as the US Congressman for northeastern Indiana 1995–2010. He was a senior staff member in the US House and Senate for a decade prior to being elected to Congress. He was one of the primary leaders of the hearings on steroid abuse in baseball. He has previously contributed articles to “The National Pastime” in Chicago, New York, and Pittsburgh. He has also contributed to three previous SABR books and two upcoming SABR books on the San Diego Padres and the Boston Beaneaters. He is retired and lives in Fort Wayne with his wife and his books.

Notes

1 Bill McMahon, “Al Spalding,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/b99355e0.

2 Peter Levine, A.G. Spalding and the Rise of Baseball: The Promise of American Sport (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985), 5.

3 Levine, A.G. Spalding and the Rise of Baseball, 82–3.

4 John Thorn, Baseball in the Garden of Eden: The Secret History of the Early Sport (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011), 207–26.

5 Ronald V. May, RPA; “Historical Nomination of the Minnie Scheibe/Bathrick Brothers Speculation House, Loma Portal,” Historic House Research for the California Department of Parks and Recreation, November 2016, 18–20.

6 “Buffrey Tells of Charles T. Page, Prominent Atlanta Man Is Dean of All Southern Baseball Exponents and Was One of the First to Bring National Game to South,” Atlanta Constitution, August 10, 1919.

7 Christopher Devine, Harry Wright, The Father of Professional Baseball (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2003), 104–5; see also Mark Souder, “When Boston Dominated Baseball” in Baseball’s First Nine, ed. Bob LeMoine and Bill Nowlin (Phoenix: SABR, 2016), 18–20.

8 Levine, A.G. Spalding and the Rise of Baseball, 75.

9 Levine, 79.

10 Emmett A. Greenwalt, California Utopia: Point Loma: 1897-1942 (San Diego: Point Loma Publications, 1978), 1.

11 Greenwalt, 3.

12 Greenwalt, 5–11.

13 Greenwalt, 12–22.

14 Greenwalt, 19.

15 Greenwalt, 19.

16 Kevin Starr, California: A History (New York: Modern Library, 2005), 31–39

17 La Playa Trail Association, Images of America: Point Loma (Charleston, S.C.: Arcadia Publishing, 2016), 48.

18 “Mrs. Spalding’s Death at Seabright,” New York Tribune, July 11, 1890.

19 Greg Kelly, “Monmouth Beach: Land of Rich & Famous,” Monmouth Beach Life, March 16, 2019. http://www.monmouthbeachlife.com/mb-history/monmouth-beach-once-land-of-rich-famous/

20 “Mayer-Spalding,” Los Angeles Times; June 24, 1900.

21 “Leaves Baseball for Mysticism,” San Francisco Examiner; March 29, 1903.

22 Thorn, Baseball in the Garden of Eden, 265.

23 Thorn, 270–71.

“Leaves Baseball for Mysticism.”

25 Katherine Tingley, Lomaland Souvenir: Panoramic View of the International Theosophical Headquarters Grounds with a glimpse of Greek Theater (San Diego: Theosophical Society), 1912.

26 Marc Lamster, “The Curious Architecture of Albert Spalding,” Design Observer, August 10, 2009. https://designobserver.com/feature/the-curious-architecture-of-albert-spalding/19878)

27 Cecilia Rasmussen, “San Diego Theosophists Had Own Ideas on a New Age,” Los Angeles Times; August 3, 2003.

28 This dollar figure likely includes his golf course because I could not locate a separate number.

29 “Sunset Cliffs History,” Sunset Cliffs Natural Park. http://www.famosaslough.org/schis.htm; “Sunset Cliffs Natural Park,” City of San Diego Park and Recreation Department. http://www.famosaslough.org/scgraphics/SCNPbrochure.pdf

30 “SCGA History,” Southern California Golf Association. http://www.scga.org/about/scga-history/part-1.

31 “Sail Ho Golf Club,” San Diego Golf Pages. http://www.golfsd.com/sail_ho.html.

32 http://www.thelomaclub.com/

33 David McCullough, The Path Between the Seas: The Creation of the Panama Canal, 1870–1914 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1977), 11–12.

34 Richard W. Amero, Balboa Park and the 1915 Exposition (Charleston, S.C.: History Press, 2013), 14.

35 “Presidio Park: A Statement of George W. Marston in 1942,” Journal of San Diego History 32, no. 2 (Spring 1986). http://www.sandiegohistory.org/journal/1986/april/presidio/.

36 Amero, Balboa Park and the 1915 Exposition, 59–60.

37 Amero, 139.

38 Spencer C. Olin Jr., “Hiram Johnson, the Lincoln-Roosevelt League, and the Election of 1910,” California Historical Society Quarterly 45, no. 3 (September 1966): 225–40.

39 Martin Shefter, “Regional Receptivity to Reform: The Legacy of the Progressive Era,” Political Science Quarterly 98, no. 3 (Autumn 1983): 471.

40 Levine, A.G. Spalding and the Rise of Baseball, 141.

41 Olin, “Hiram Johnson,” 235.

42 “Primaries Favor Spalding, Captures Majority of Counties in California Senate Race,” New York Tribune, September 6, 1910.

43 William D. Page, “A Political Crime,” Spalding’s Official Base Ball Guide, March 1911.

44 May, “Historical Nomination of the Minnie Scheibe/Bathrick Brothers Speculation House,” 11–21.

45 Amero, Balboa Park and the 1915 Exposition, 14–15.