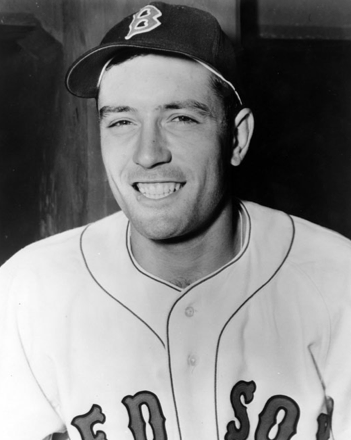

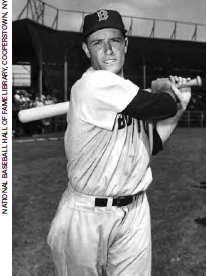

Jim Piersall’s Tumultuous 1952 Season

This article was written by Neal Golden

This article was published in Fall 2017 Baseball Research Journal

Jimmy Piersall’s death on June 3, 2017, provided an occasion to recall his rookie season of 1952 that he began playing a new position—shortstop—for the Boston Red Sox, continued with AA Birmingham, and ended in a mental hospital. His is the inspiring story of a young man overcoming a serious health problem to craft a productive 17-year major league career.

On our trip through Jim’s rookie season, we will discover the following:

- Piersall exhibited erratic behavior the previous season with AAA Louisville.

- He quickly became the favorite of the Red Sox fans with his hustle, competitiveness, and showboating tactics.

- He lost his starting position at shortstop because of his lack of hitting but later returned to the lineup in right field.

- was an unusual clubhouse incident that the Red Sox tried to hush up.

- His departure stirred a storm of protest from fans.

- Some Boston reporters claimed that the real reason for Piersall’s demotion was the jealousy of the “old guard” on the club.

- Only a couple of writers suspected that Piersall was mentally ill.

- behaved even more erratically with Birmingham, leading to his hospitalization.

- Medical examination revealed serious mental problems that took a month and a half of treatment to alleviate.

- Through it all, Piersall’s saga riveted Boston, with numerous front-page stories on his travails.

James Anthony Piersall grew up with a demanding father who dreamed of a pro baseball career for his son, and a mother who spent multiple stints in mental hospitals. He was high-strung as a boy and plagued by headaches starting as a teenager. He had difficulty keeping still.1

Piersall began his career in the Red Sox farm system at age 18 in 1948. Boston scout Neil Mahoney heard about a “schoolboy wonder” in Waterbury, Connecticut. Mahoney “sold him on the Sox, stealing him out from under the Yankees.”2 Piersall sparkled in center field for four years in the minors.

When Jim reported to Red Sox spring training camp in Sarasota, Florida, on March 1, 1952, new manager Lou Boudreau announced that he was shifting him to shortstop. Piersall’s best position was center field, but Boudreau was obviously pleased with veteran Dominic DiMaggio in that position. Lou didn’t feel the same way about 33-year-old Johnny Pesky, a fixture of the Red Sox infield since 1946. Pesky had kept his starting shortstop job in 1951 even though Boston had signed a capable shortstop in Boudreau (one year older than Pesky) following his release from the Indians after the 1950 season. Pesky had a .313 batting average in 1951 and scored 93 runs. Furthermore, general manager Joe Cronin gave Pesky his first raise in two years: $2500.3

But Boudreau took over as skipper from Steve O’Neill for the 1952 season and he didn’t believe Pesky—who “was troubled all spring with his legs”4—provided his best option at short. He even went on record as favoring third baseman Vern Stephens, who had held down the shortstop position for the 1948, ’49, and ’50 seasons.5 Instead, Boudreau had Pesky work out at second base to fill the vacuum left there by the retirement of Bobby Doerr.6 “Piersall needs seasoning, game experience,” added Boudreau. “He’s going to see plenty of action in the exhibitions down here. And he’s going to make mistakes. He’s still got a lot to learn, but he’s anxious and willing. He’ll come along and be a great major league shortstop.”7

Boudreau’s announcement left writers scratching their heads. Joe Cashman of the Boston Daily Record could recall many instances of a player starting at shortstop before shifting to the outfield—Joe DiMaggio and Mickey Mantle being two famous cases. “But you can count on the fingers of one hand the great shortstops…who started out in any other position. And the only one of these who moved from the outfield…was the immortal Honus Wagner…”8 Still, Cashman liked what he had seen so far. “Considering his inexperience, Piersall is doing a creditable job in the strange position.” And the scribe added, “if he can become a good shortstop he’ll be of more value to the Sox than he would be as an outfielder.”9

During the first week of spring training, Piersall passed around cigars to celebrate the arrival of a second daughter back in Scranton, Pennsylvania. Jim now had an additional mouth to feed. In his autobiography Fear Strikes Out, he described himself at that time as “a scared, tense kid” who put tremendous pressure on himself to earn money to support his family.10 And now he was being asked to learn a new position. “It’s impossible!” he wrote. “I’m not a shortstop. I’m a center fielder…It doesn’t make sense. What makes them think they can make a shortstop out of me? Just trying to shift from the outfield might ruin me.”11 Still, he celebrated the new baby’s arrival by making a leaping catch of a liner with his back to the plate. He also showed his inexperience at his new position by failing to cover second on a relay from the outfield and dropping a popup.12

His athletic ability trumped his fears. Reporting on a March 13 exhibition game, Cashman wrote: “In addition to getting the lone Boston run and only extra-base blow, Jim Piersall had a busy, brilliant day at short…he handled eight chances flawlessly and sparkled with Ted Lepcio on two double plays.”13 On March 14, John Drohan wrote in the Boston Traveler: “The conclusion is that Piersall…has impressed the Sox so favorably that he’s going to be carefully considered for the varsity job before being sent to Louisville. It was the original intention to give him a thorough schooling on shortstop technique and send him down to Louisville for the balance of the 1952 season.”14 That afternoon, “Jim Piersall had another brilliant day at shortstop and got two hits.”15 Then “another impressive day at shortstop” in the next game.16

Cashman continued to laud Piersall. In a March 24 article on the top rookies in spring training, he wrote: “Probably [the] most remarkable of the entire rookie contingent this spring is Piersall. Here is a lad who has spent his entire baseball career…as an outfielder and today, after less than 10 weeks of infield experience, is the best defensive shortstop on the Sox squad.”17

On March 30, an article appeared in the Louisville Courier-Journal that cited disturbing behavior from Piersall’s past that called into question his ability to handle the stress of playing for the Red Sox. Jim played the 1949 and 1950 seasons and 17 games at the beginning of the 1951 season for Louisville, the Red Sox’ farm club in the AAA American Association. But even though he was batting .310 to start the ’51 campaign, he was demoted to AA Birmingham at his own request because he had been relegated to the bench by Louisville manager Pinky Higgins, who had to play another promising prospect in his place.18 In the Courier-Journal article, Higgins said this about Piersall from the Colonels’ spring training site: “I’ve never seen a kid change like he’s changed. Never heard a peep out of him at Boston’s pre-spring training rookie camp. He was really docile. You wouldn’t have recognized him.” The reporter, Tommy Fitzgerald, explained the background of Higgins’s comments. “With the Colonels, [Piersall] didn’t seem to be a kid in complete control of his emotions. He was inclined to fly off the handle, being sensitive to jibes from the stands and from the opposing dugout. He also had a tendency to rub his own teammates the wrong way. He has all the ability in the world, but he wasn’t the best-liked ballplayer…This was a factor in Jimmy’s going from the Colonels to Birmingham last season…Now Jimmy seems to have grown up. Jimmy was a high-strung kid, over-eager and ambitious, in the past. A little maturity and experience seems to have changed his disposition.”19

Fitzgerald reported Joe Cronin’s appraisal of Piersall to that point in spring training. “I’d say he has a perfect temperament for a shortstop.…Aggressive and a take-charge guy. He’s outgrown those other little faults of his.” Cronin added: “He can go to his left, to his right, come in and go back as well as any shortstop in America.…If you never knew he was a converted center fielder, you’d think he had been playing shortstop all his life.”20 Unfortunately, Cronin’s assessment that Jim had “outgrown those other little faults” proved to be wishful thinking.

As the Red Sox broke camp, observers felt Piersall had clinched a spot on the roster. Cashman: “Last season Allen Richter, playing for Louisville, was chosen the All-Star shortstop in the American Association. Jimmy Piersall…was the regular center fielder for Birmingham in the Southern Association. Today, Piersall rates as the Red Sox second-string shortstop and Richter…must return to Louisville unless he can persuade a big-league club to buy him…That’s correct. An outfielder from Double A, who never played a game at short until two months ago, is now picked by an all-time shortstop great named Lou Boudreau over a boy who was the standout shortfielder in Triple A.”21

Then Cashman revealed that “Boudreau’s present plan is to use Vern Stephens at short for the first six or seven innings of games and then throw Piersall in for defensive purposes when the Red Sox happen to be in front. But many are predicting that before the regular season is very old, Piersall will be a regular nine-inning shortstop.”22 When the Red Sox arrived in Boston for their annual three-game series with the crosstown Braves right before opening day, Boudreau talked as if Piersall were his starting shortstop. “Piersall will have to learn to play a different way in every American League park. I intend to show him the difference in each park as we travel around the circuit.”

Sure enough, when the Red Sox opened the regular season at Washington, Piersall was in the starting lineup at shortstop with another rookie, Ted Lepcio, manning second. Boudreau relegated veterans Stephens and Bill Goodman to the bench, and shifted Pesky to third base. Batting sixth, Jimmy smacked a double, “the longest drive of the game,” in four trips to the plate. Piersall also “handled everything that came his way at short…”23

Despite playing without Ted Williams, who would miss most of the 1952 and 1953 seasons after being recalled to military service during the Korean War, the Red Sox got off to a good start. By April 23, Jimmy was batting .400 in his first ten games and getting good reviews for his fielding. Following a victory over the Yankees April 23, Mike Gillooly of the Boston American wrote: “The Red Sox have now won eight games, more than any other club in either league. They have won them principally through the keystone combination of Jimmy Piersall at short and Ted Lepcio at second. These whiz kids cover so much ground they make average pitching look good.” As late as May 7, Piersall was still 13 points above .300 with seven doubles and seven RBIs—more production than anyone expected from him.24 An instant hit with the fans, Jimmy was invited to speak at many sports gatherings.25

But the seeds were being planted for the weeds that would soon choke Jim’s rookie season. Piersall irritated Yankees infielder Billy Martin and vice-versa. The two started razzing each other in spring training, and Billy kept up the attack during the Yankees’ two-game series at Fenway Park April 23–24.

Piersall began to exhibit difficulties with umpires in a May 11 game at Yankee Stadium. When Jim Honochick ruled Gil McDougald safe because first baseman Billy Goodman failed to tag him after receiving Jimmy’s wide throw, half the Sox squad stormed the umpire. Jim was so incensed that he was chased from the game “for using rude language.”26 It’s possible perfectionist Piersall was irate because the safe call gave him an error.

No articles reported any conflicts between Piersall and Martin during that series in New York. However, it can be deduced from later events that the two continued to jaw back and forth during the three games.27

The feud with Martin came to a head May 24 before a game at Fenway Park. During infield practice, Piersall taunted the Yankees. Martin, warming up on the sideline, told him to shut up. The rookie responded by telling Martin he listened only to “guys who actually played.” Following some more give-and-take, Jim called Billy “a dago busher.” With that, Billy dropped his glove and challenged Piersall to meet him in the players’ runway under the stands.28 Martin, in his own words afterwards, “hit him good twice,” dropping Jimmy to his knees and drawing blood before Piersall closed in and grappled with Billy. Piersall’s shirt was ripped. Coach Bill Dickey of the Yankees and Sox pitcher Ellis Kinder separated the combatants.29

Out of the starting lineup since May 17 when his average dropped to .255, Piersall heckled Martin throughout the game from the Boston bench. Afterward, Jim implied his frustration at not playing was a factor in his tangle with Martin. “What’s there for me to say? He’s hot-headed. I’m hot-headed because I’m not playing.…He was on me pretty good in New York. I don’t know why.”30 Martin said, “He made some pretty bad remarks. I may be smaller than he is, but I’ll fight anybody who makes those remarks to me.”31 Boudreau seemed unperturbed by the fracas. “They’re both scrappy kids, quick-tongued and quick-tempered and they’ve been going at each other since spring training.”32

Lou didn’t mind Jim tangling with an opponent, but he had a different opinion when Piersall took on a teammate. Two days after the fight with Martin, Jim got into a shoving match with Mickey McDermott, who needled him about his set-to with Billy. “Verbal barbs were exchanged in the Sox clubhouse and when Piersall leaped to his feet, McDermott pushed him backwards into his open locker. Then Piersall charged the lanky pitcher—noted as a bench jockey and ribber—and shoved him backward over a couple of chairs to the floor. The hurler quickly realized the steamed-up Piersall was in an agitated mood from the Martin incident and apologized. They shook hands and that ended the affair.”33 Boudreau declined to take disciplinary action against either player but declared, “I have told them…that I do not want any fighting among the players.” Concerning Piersall’s second offense in three days, the Boston skipper said, “Just as long as he plays ball for me, that’s all I ask.…Riding another ball player is all right providing you know when to stop. I want the kid to play hard, aggressive baseball.”34 On June 1, Piersall was chased from the bench by umpire Ed Hurley, who claimed Jimmy “was hurling profanity at him.”35

Two days later, the Red Sox and Tigers announced a blockbuster nine-player deal. Boston gave up Pesky, first baseman Walt Dropo, third baseman Fred Hatfield, outfielder Don Lenhardt, and pitcher Bill Wight. Boston received third baseman George Kell, shortstop Johnny Lipon, outfielder Hoot Evers, and pitcher Dizzy Trout. Asked to clarify Piersall’s status on the roster following the shakeup, Boudreau said he would be a reserve shortstop ready to take over for Stephens and available for center field for DiMaggio in event of an injury to either player.36

Jim made the headlines again by walking out of a squad meeting prior to the June 3 home game with Cleveland. Ed Costello of the Boston Herald found the volatile rookie in the dugout crying. Asked why he was distraught, Piersall said he had been told earlier that day that he would start at shortstop, but when Boudreau read the lineup to the players, Lipon was at short. “I just want to play. That’s why I pop off on the bench.…I’ve worked hard.…When I’m not playing, I blow my top.” When Costello advised apologizing to the manager, Jim wiped the tears away and, with head down, went back to the meeting.37

Jimmy returned to the starting lineup June 5 in right field in place of Clyde Vollmer, who suffered from a stiff neck. Boudreau: “Jim moves good out there … he’ll be all right if he starts hitting.”38

Detroit came to Fenway Park for a five-game series starting June 6 that attracted large crowds because of the recent trade. The Tigers’ bench jockeys rode Piersall unmercifully, calling him “Johnnie Ray” because of the aforementioned crying incident.39 (Ray was a contemporary singer known for crying while singing.) Commenting on the final game of the series, Austen Lake wrote in the Boston American: “The strangest transfiguration of all is the sudden, almost hysterical fondness the right field patrons are showing toward Jim Piersall, the Sox problem child and fussbudget who has been kicking up all kinds of ruckuses this spring. Lou paroled Jim in right field on his promise of good behavior with the proviso he wouldn’t jaw back and forth with the fans. But it was too much for Jim who just can’t resist screwing his neck around and giving wisecrack for each jape. But he’s doing a fleet-footed job of work too and hauling down flies, both long and short. And he gets his quota of hits. So the fans…like Jim for his small antics and he-man competence.”40

In the last game against Detroit that series, Piersall smacked a solo homer. On June 11 against St. Louis in Fenway, Jim started a six-run ninth-inning explosion against ancient Satchel Paige to pull out the 11–9 victory. “The brash rookie beat out a bunt to open the inning and then practically went into hysterics on the base path with a series of pantomimes that bewitched even an old-timer like Satch.…Satch seemed almost relieved when he walked Bill Goodman to force in Piersall with the first run of the inning…but Piersall kept riding him from the bench…”41 After the game, 46-year-old Paige said, “I never saw any man do those things anywhere.” Once again, Jim was defiant. “I don’t care what anybody thinks about what I was doing. We won the ball game, right? And winning ball games is what I’m after no matter what goes on.”42

In his article on the victory over the Browns, John Drohan wrote, “Jim Piersall…threatens to become the greatest gate attraction the Red Sox ever had…the Sox have, in Piersall, a player different from any one ever on the club. ‘I told Satch I was going to bunt,’ said Jim, ‘when I went up there in the ninth. He looked at me kind of surprised. But he didn’t say anything. Then, when I put the bunt down and reached first, I went to work on him.’…Piersall mimicked Satch’s fluid windup. He held on to his arm, yelling, ‘Satch, you won’t be able to wash your face tomorrow, your arm will be so tired.’…Catcher Clint Courtney said, ‘I think that Piersall’s crazy. I never saw such a crazy guy in baseball.’”43

In the last game of the subsequent three-game series in Chicago, Boudreau benched Piersall in favor of Vollmer. Cashman wrote, “Vollmer for Piersall is construed as a move to discipline rookie Jim, whose eccentric actions have the whole league talking and the fans flocking to see him. Not since Harry Hooper’s days have the Hose had a right fielder who could field and throw and run like Piersall. Moreover he hit .341 [actually .333] since going to the sun field. Along with all that, he’s the most refreshing and hustlingest guy the Hose have had in ages. If he’s forced to become strictly conventional, the Red Sox will ruin the best gate attraction in the league. And while he’s sitting out, the Sox will be depriving themselves of one of the keenest competitors and most talented rookies in the business.”44

Jim appeared in the next two games as a late-inning replacement for Vollmer. He returned to the starting lineup for all four games in Cleveland but went only 2-for-12. In one of the games on the Western swing, Piersall sped in from his outfield spot to catch a low liner with his gloved hand while tipping his cap to the crowd with the other.45 On June 25, Mike Gillooly wondered why Piersall hadn’t started the first two games in Detroit since he had hit .526 and knocked in seven runs against the Tigers in earlier series.46

The games in Detroit earned Piersall a $10 fine from American League president Will Harridge for “fraternizing” with the Detroit players. Jimmy told reporters before the first game against Washington back in Fenway Friday night, June 27, that he had written a letter to Harridge. “I told him I’d be paying some umpire’s salary before the season was over.”47 Writing that self-incriminating line to the league president showed a lack of judgement, as did telling the media about it.

Despite a “We want Piersall” banner in center field, Jim did not enter the game against the Nationals until the seventh inning as a defensive replacement. He made a backhanded catch of a screaming liner and immediately whirled toward the bleachers, removed his cap, and bowed. The fans loved it.48

Then came the bombshell. The Red Sox “astonished the baseball world”49 at noon on Saturday, June 28, by abruptly sending Piersall to Birmingham of the AA Southern Association just 12 hours after Boudreau had announced that Jimmy had won back a starting spot in right field. Piersall cried like a baby in the clubhouse when he received the news. Talking to reporters before boarding a flight to Birmingham, Jim blamed coach Bill McKechnie of all people. “Here I am playing good, hustling ball, and what do I get for it? McKechnie ships me out of town after Boudreau told me Friday night I was starting Saturday’s game…I can’t figure the reason. Don’t they want to win? Didn’t I help get them up there?”50 Jimmy’s totals with the Red Sox for 56 games included a .267 batting average (43-for-161), 16 RBIs, 28 runs, 8 doubles, 1 home run, and 28 walks.

Then came the bombshell. The Red Sox “astonished the baseball world”49 at noon on Saturday, June 28, by abruptly sending Piersall to Birmingham of the AA Southern Association just 12 hours after Boudreau had announced that Jimmy had won back a starting spot in right field. Piersall cried like a baby in the clubhouse when he received the news. Talking to reporters before boarding a flight to Birmingham, Jim blamed coach Bill McKechnie of all people. “Here I am playing good, hustling ball, and what do I get for it? McKechnie ships me out of town after Boudreau told me Friday night I was starting Saturday’s game…I can’t figure the reason. Don’t they want to win? Didn’t I help get them up there?”50 Jimmy’s totals with the Red Sox for 56 games included a .267 batting average (43-for-161), 16 RBIs, 28 runs, 8 doubles, 1 home run, and 28 walks.

Boudreau told reporters, “I changed my mind about him this morning after saying last night he would start today’s game. I sent him down to straighten him out. He’s got to hit better. I told him so. My decision wasn’t made overnight. I know Piersall’s antics made him popular with the fans and the baseball writers. But I had to consider the other 25 or 30 men on my club. We’re trying to win and Piersall was a disturbing influence.” Lou said that Jimmy told him, “Maybe I deserve this, but I’ll be back.”51 Lou didn’t mention it, but he had asked coach Bill McKechnie to talk to Jim to no avail.52 GM Cronin reinforced his manager’s explanation. “I’ve never seen Lou so nervous. After he sat shaking in my office for some time, he finally told me Piersall had to go for the good of the club. Lou said time and again he had begged Piersall to behave himself but that he just got worse every day.”53 Cronin cited the fact that Jim had stood clowning at the plate by mimicking the pitcher while taking three strikes in the game against the Nationals.54

Despite these explanations, Gillooly asked, “Who’s running the ball club? Not Boudreau, evidently. And perhaps not even Joe Cronin, who earlier in the week had called Piersall ‘My Boy’ and praised the ‘bush league’ stuff Jimmy pulled to defeat…Satchel Paige…It’s been bruited about for weeks now that a quintet of Sox five-year men have been complaining about Piersall’s pranks. Reliable reports have it that they went to Boudreau and asked that he release the kid…‘He lowers the dignity of the club’ was their complaint.”55

“Thunderous disapproval was registered by rabid Red Sox fans” at Saturday’s game when they learned that their favorite had been demoted. One fan expressed the feelings of many when he said, “I came out to the game today just to see Piersall play. I read in the papers that Boudreau said he was going to start in right field. Now I find they shipped him out. What’s the matter with that Boudreau anyway?” Another fan said, “I think he’s the victim of the jealousy of some other players. He’s a natural clown and was getting a lot of publicity which some of the older players resented.”56

Jim’s wife Mary and his father were bitter about the demotion. Both felt he behaved as he did because he thought management wanted him to do so. Mary said, “When he had the battle with Billy Martin, they seemed to approve of his type of bench jockeying. Jimmy thought that was what they wanted, a player full of fire and with the desire to win.” His father blamed Jim’s teammates. “I know they were giving him the silent treatment. Ted Lepcio was the only one who would talk to him. What kind of men do they call themselves? It looks as though they couldn’t stand a kid who was as good as some of them, full of determination and trying to set a fire under them. They can relax now. They don’t have to worry about losing their jobs to a rookie who was playing better ball than they were.”57

Boston American columnist Austen Lake sensed that something was wrong with Piersall. “…the Red Sox have produced some weird characters during the last seven, neurotic years. But the latest and daffiest is Jim Piersall…Somewhere between spring’s dry stubble and summer’s green grass, Piersall became a one-man psychopathic ward—either by plan or by nature. Both on and off the field his moods merged into each other in a maniacal blur. He babbled half coherently, wept impulsively, stormed without provocation, laughed convulsively, gyrated, quarreled and jigged—sometimes separately, sometimes all at once. So is this a studied ACT, self-designed to increase his public appeal and thus fatten his future contract as a box office attraction? Or did some of Jim’s cerebral rivets work loose since last March when he was a docile, industrious, church-going youth…? …When the Sox opened their season Jim turned loud, belligerent, burlesque and a cockle-burr under his team’s skin.…It was funny for a while and the fans welcomed Jim as a comic relief…Still what puzzles me from believing that this was coldly calculated by Jim was his immediate and frenzied flood of real tears when benched or scolded. And his black funks when rebuffed! His angers are violent and sudden…Also he had a chronic persecution complex and complained loudly that he was a target for clubhouse politics, dugout prejudices, and managerial discrimination. Also, from being a civil-tongued, courteous man, calmly polite as he was in the South, he employed harsh obscenities, offensive even to the rough-spoken company of ball men.”58

Another writer concerned about Piersall was Bill Cunningham. He wrote in the July 4 Boston Herald: “The Boudreau decision to bar himself to the press immediately after ball games is said to stem from the fact that ‘some of the writers’ were not too kind in their reporting of the Piersall sacking. In other words, they wrote sympathetically of the young man. Although not involved, it seems to me that was the human way to handle it. Something’s wrong with that kid. He needs help, not abuse.”59

Piersall was no stranger to Birmingham, where he compiled what he later called “one of the greatest baseball seasons I’ve ever had.”60 He batted .346 in 121 games in 1951, helping lead the Barons to both the Southern Association title and the Dixie Series crown over the Texas League champions. He told his wife before leaving Boston that he was glad he was sent to Birmingham because he had a lot of friends there.61 He made an immediate impact when he returned to The Magic City. He went straight from the airport to the ballpark, suited up, played center field, and hit a three-run homer. The ball cleared the 60-foot scoreboard in left center field 381 feet from home plate.62

Two days later, Piersall, his voice quivering, told the Birmingham diamond club, “From now on I’m going to do my best to control my behavior.”63 But he had already begun the antics that got him demoted. In the Sunday doubleheader the previous day, he “pranced out of the players’ tunnel, twirling a bat like a drum major’s baton,…and laid down in the outfield when the rival pitcher came to bat.”64 He went to bat left-handed on one occasion. He hit a home run that earned him a $50 prize but also heckled the Memphis batters from the outfield, where he continually whistled. Twice he left the field to get water, once while he was a runner on third and again when he was batting. He doffed his cap every time he passed the Memphis dugout. As in Boston, the hometown fans loved his antics while the opposing players hated them.65 Eddie Glennon, the Barons’ general manager, called Cronin the next morning and told Joe, “That boy certainly has changed since we had him down here last year. Maybe I can stand it if we are winning, but some of those freakish stunts of his will become quite irritating when we are losing.”66

With the Barons in New Orleans on July 2, a story broke in Boston that explained why Piersall had been shipped out so suddenly. The words came from Ronnie Stephens, four-year-old son of Red Sox shortstop Vern Stephens, and were spoken to a Boston American reporter: “Jim Piersall held me over his head and spanked me three times.” The boy continued, “I socked him one and told him he was a naughty boy. I cried for 10 minutes.”67 The incident occurred during the eighth inning of the game against the Nationals the previous Friday. When confronted by reporters while in Philadelphia for a series with the Athletics, Boudreau admitted that the spanking was the last straw. Lou realized that Jimmy might have been fooling with the boy but hit him “a little too hard.” Vern Stephens had not known about the incident until the story broke. His reaction was, “It’s a good thing they sent Piersall out of town away from me.”68

When contacted in New Orleans, Piersall didn’t deny that the incident happened but said he intended no harm to the youngster. “I did go into the clubhouse during the game, and Vern’s young boy, a cute kid, was there. I started fooling with him and I guess I gave him a little spank on the seat of his pants that was a little too hard because he started to cry. I kidded with him then and asked if he was all right. I have two children of my own and wouldn’t for a minute stand for anyone intentionally hurting them. I certainly didn’t mean to hurt Stevie’s boy and told him so Friday night and Saturday morning.” Vern admitted that Jim came to him and asked him if Ronnie was okay but said that he didn’t understand what Piersall was talking about.69

In acknowledging the incident, Boudreau told reporters, “I couldn’t announce why I was sending Piersall down to Birmingham for obvious reasons, but his action Friday night was the culmination of a series of incidents that forced me to drop him from the club.” The next day, after reading Jim’s explanation, Stephens changed his tune and said that he was sorry for Jim, and that he realized the spanking was meant in fun. “And I’m sorry that the news of the incident was taken to Lou Boudreau.” When told what Stephens said, Piersall replied, “Gee, that’s wonderful. He is such a grand guy.”70

It also came to light that the person who “squealed” on Piersall was clubhouse attendant Johnny Orlando, who was present with Ronnie and his nine-year-old brother. Vern Jr. also defended Jim. “He wasn’t hitting him hard, though. Ronnie cried because Ronnie is tender. Piersall was just playing, I think.”71

Boudreau also clarified what bothered him about Piersall’s behavior. “Jim is such a good outfielder that he can handle the job despite his clowning. But it was at the plate and off the field that burned me up. He’s not good enough a batter yet to fool around at the plate. Time and again, I told him that he has to bear down at the plate. But he kept up the clowning.”72

Bob Dunbar of the Boston Herald called the spanking incident “extremely unfortunate. Piersall may be a lot of things, but he certainly isn’t a child-beater. As a matter of fact, most of the youngsters around Fenway Park love him. Jim used to get to the park…and play ball for a couple of hours with boys like Tommy Cronin, son of the Sox general manager.”73

Piersall gave some clues about his mental state when he spoke by phone from New Orleans to Boston Daily Record reporter Paul Whelton on July 3. Jim said, “That business about a spanking really knocked me for a loop. The thing was just a bit of fun in passing and while I was swinging the little fellow in the air and setting him down again in the clubhouse, I did spank his fanny a couple of times—just like I do with my own kids—but only in fooling. He did start to cry and maybe I did hit him too hard, but I thought he probably was more frightened at being swung into the air. Boy, you don’t think people up there really believe I’d hurt a child, do you?” Told that the consensus in Boston was that it “was just one of those things,” Piersall said, “Good!” He then revealed his plan to send Ronnie a telegram to tell him he regretted what happened. He even told the reporter what he would say and asked how it sounded. “You don’t figure anybody’ll twist that to make it sound like more popoff?” Assured that “nobody of sound mind” would, Jim said, “That’s swell. It relieves my mind.” Then Whelton asked, “When do you figure you’ll be back with the Boston club, Jim?”

“I’m not even going to guess. I’m just playing ball. I guess I’m gonna be a settling down guy—if it takes all summer. But I’ll be back. I’ll be up there.”

“There’s a light still burning in the window.”

“Brother, I hope so. Don’t let anybody blow it out.”

“You’re the only one can do that.”

After a moment of silence, Jim replied, “I get you. I know what you mean.”

He thanked Whelton for the talk, then said he had to go “send that wire.”74

We can’t know whether the revelation of the spanking exacerbated Piersall’s emotional problems. But we do know that he went beyond anything he had done before in the five-game series against the Pelicans in New Orleans July 2–5. In the first game, Piersall, playing center field, “never once stopped his monkey shining or his jabbering. He rode [Pelicans pitcher Ramon] Salgado, flaunted the authority of the umpires and indulged in all sorts of unorthodox clowning.”75 He also rushed in from his position holding his hands up for “time” and went to the bench without explanation. It turned out that he needed to rearrange the bandage on a foot blister. Southern Association president Charlie Hurth, in attendance, was not pleased.

During the series, Piersall also did the following:

- Never sat on the bench when his team was at bat but instead stood just outside the dugout with his back to the field, waving a towel to the crowd

- While a runner on first base, walked to home plate to whisper something to the batter and, on another occasion, left the batter’s box to speak to the runner on third

- Tried to squint down at the catcher’s signals during an at-bat, walking out of the box before one pitch with two fingers down to show what the catcher had called

- Used the glove of Pelicans’ outfielder Frank Thomas after the latter made a spectacular catch to end the half inning (Players left their gloves on the field between innings in those days.)

- Rode Pels pitcher Ed Wolfe throughout every one of his plate appearances against him and continued to heckle Wolfe each of the three times he reached first base via a walk. On one of those occasions, Jim walked from first base to the mound to accuse Wolfe of throwing at him.

Matters got out of hand in the final game of the series when Jim’s actions caused his own pitcher, John McCall, to lose his cool. In the top of the sixth, a big rhubarb broke out when home plate umpire George Popp ruled a ball foul. Birmingham manager Red Mathis was ejected, and several players berated the ump. Piersall took no part in the fuss but instead mimicked the umpires, his manager, and some of the players. “He grabbed up a bat and knelt at the plate; then raced hither and thither, laughing good-naturedly…”76

When Popp ordered play to resume, Jim “loitered about the infield, paying no attention to the remonstrations of his teammates to go out to his position. McCall, who was anxious to get the game going, threw a ball in Piersall’s direction and far into center field. He doubtless figured that would make the playboy go to the outfield. Umpire Popp ordered him to go and Piersall slowly walked out. He kicked the ball as if in soccer, ran after it, picked it up and threw it to the scoreboard boy. The boy, who was at the top of the high board, tossed it back; Piersall returned it.” That was too much for Popp, who ejected Piersall from the game. As Jim ran past the pitcher’s mound, McCall gave him a tongue-lashing.77

Shortly afterward, Piersall, still in uniform, appeared in the grandstand among a group of about 500 New Orleans Recreation Department boys. With many fans watching him instead of the game, he led them in a chant, “We want Piersall.” Then Jim disappeared into the dressing room. Returning in street clothes, he joined league president Hurth in his box seat and had the audacity to heckle Popp as well as Pelicans manager Danny Murtaugh while sitting next to the man who had the authority to fine and/or suspend him.78

Veteran Times-Picayune sportswriters Harry Martinez and Bill Keefe had mixed opinions about Piersall. On the one hand, wrote Martinez, “baseball needs more players like Jim Piersall…to put more life into the game.…Call him a ‘screwball,’ ‘showboat’ or what you will, he has color, and any individual who can give the fans so many laughs is valuable to a ball club. After all, the fans go out to the parks to be entertained.…Piersall is a ‘take charge’ guy. Whether he is at bat, on base, or in center field, you can’t help keeping your eyes glued to him.…Piersall can afford to clown a bit because he is a good ballplayer. His only fault is, he overdoes his act.”79

Keefe had similar sentiments. “The boy may not be a big-league ball player and may be a big-league screw ball. Don’t, however, sell him short as a ball player and don’t think too harshly of him because he gets a lot of fun out of baseball. He has more points to admire than to condemn…He loves to play and he puts out 100 percent effort on every try.…When he keeps within bounds he’s refreshing, original and entertaining. You can’t help but like him…” However, “Unless he curtails some of his activities, he isn’t going to get along with any manager or with any teammates.”80

After the incident with pitcher McCall, Keefe changed his tune. “Up until about 5 o’clock Saturday evening I shared with the baseball writers of Boston the opinion that Lou Boudreau…and his players had taken an unfriendly, unjust and narrow-minded stand against Jim Piersall…Came late Saturday afternoon and I was compelled to admit to myself that the Red Sox had not rebelled against Piersall because they were envious of the attention he attracted, and Boudreau had not demanded his removal because Boudreau disliked seeing the boy monopolize the limelight. It became apparent to me that Boudreau and the Red Sox wanted to rid themselves of Piersall because they realized he was hurting the play of the team, just as the Birmingham players in the Southern Association are beginning to learn that Piersall is a thorn in the side of any team of ambitious ball players.”81

Yet Piersall still had his defenders in the American League. At least two managers in Philadelphia for the All-Star game, the Athletics’ Jimmy Dykes and Cleveland’s Al Lopez, praised Jim. “Crazy or not,” commented Dykes, “I’d take Piersall any day. He’s a heck of a ball player…”82 Browns manager Marty Marion praised Piersall during a series in Boston right after the break. “Baseball needs colorful, aggressive players of the Jim Piersall type. I don’t mean I approve of all the things Piersall did. He went too far at times. But if he could be tamed to the extent where he wouldn’t upset his own club and still show the life and fight he did when with the Sox, he could be a great asset.”83

When the Southern Association reached its All-Star Game break, Jim returned to Boston to bring his wife and children to Birmingham. However, he told the Boston press, “I’ve changed my mind. It’s too hot to move so I’m going back alone.” He also reiterated his determination to return to the Red Sox. “I’ve got a million dollars’ worth of ability and I’m going to prove it to Lou Boudreau and Joe Cronin. Maybe they think I’m a screwball but I’m going to prove to them that I can play the kind of ball that wins pennants.…It seems that when a fellow gets a reputation, everybody wants to get in on the act. Last Sunday everyone criticized me spitting on an umpire. Heck, I didn’t spit on any umpire. I was just talking to him…”84 Piersall also called Cronin to ask to be restored to the Sox roster. According to Jimmy, Cronin was willing but Boudreau was not. “I promised to clam up and stick strictly to baseball, but it didn’t get anywhere except Joe said, ‘Go back to Birmingham and behave. Maybe something will happen later.’” Jimmy stopped by Fenway Park and picked up “a bale of mail” that had been sent by fans. “Most of the fans tell me to behave myself and I’ll be back in Boston. I think they’re right.”85

Meanwhile, Keefe took an informal poll of owners and managers of Southern Association teams who were in New Orleans for that circuit’s All-Star game. “None wants to be quoted on Piersall’s threat to baseball—naturally. No man likes to be the cause of losing a man his job—especially when it’s a married man with a couple of kids. But most of the men have spoken to Birmingham ball players and they all agree that the Barons themselves are the sufferers. They merely point out that no player wants to room with Piersall. A few of them scoff at the story that Piersall uses no offensive language. They offer to prove that the young man has been very offensive in his cussing in hotel lobbies, as well as on the ball field.”86

When play resumed in the Association, so did Piersall’s antics. The Pelicans played a series in Birmingham a week after the bizarre set in the Crescent City. A Life magazine photographer was present on July 12 when Piersall razzed Pels pitcher Salgado just as he had in the previous series. Upset by what Jim was doing, New Orleans outfielder Frank Thomas went after Jimmy. Players from both teams crowded around the pair, and no blows were thrown.87

Up in Boston, Piersall received support from a surprising source—Dave Egan of the Boston American, famous for his long-running criticism of Ted Williams and the Red Sox front office.88 “…men who have led the Red Sox to defeat after defeat over a period of many years actively resented young Jimmy Piersall from the moment…he first set fiery foot in the Sarasota training-camp.…He disturbed them…because he said too much. He jogged them out of their comfortable ruts.…He challenged them to work as feverishly as he worked. He demanded that they be pugnacious ball-players, not weary businessmen.…And he got what the old guard, in so many lines of endeavor, too often gives the young. He got the works, with a capital W.”89

Egan added a twist to the spanking story. “On a sunny April day in Sarasota more than a year ago, [Piersall] felt impelled to stiffen Johnny Orlando, the clubhouse custodian who is a member in good standing of the old guard. He was stepping to the plate in batting practice, with one of Dom DiMaggio’s bats in his hands, when Orlando roughly intruded himself and attempted to wrest the bat from him…It was none of Orlando’s business in the first place, and Piersall had been given permission by DiMaggio to use the bat in the second, and Orlando had laid rough hands on him in the third, but to men who want no cloud in their sky, … this was as good an excuse as the next to brand him an undisciplined trouble-maker.…I am saying that what the embittered old guard of the Red Sox wanted to happen did happen, when Jimmy Piersall was sentenced to an indeterminate term in Birmingham, and this is my accusation: that men who have become fat and rich at the expense of Tom Yawkey and the baseball fans of New England did nothing to help, and everything to hurt, the most magnificent prospect that baseball has known in a generation.…Now there are dozens of stories about the boy: how he taunted the placid Vic Wertz of the Tigers into such an unwonted fury that Wertz invited him under the grandstand; how he told Cleveland newspapermen that only George Kell excelled him on the Red Sox squad…how he imitated the curious lope of Dom DiMaggio…and how the same Johnny Orlando who had been set on the seat of his trousers in Sarasota 15 months earlier galloped to Boudreau with the fantastic story about Vern Stephens’ child…Piersall, in other words, has been the victim of a palace plot.”90

Anton Demers wrote a column that appeared in the Boston American the next day under the large headline, “Lipon Over Piersall?—No!” He wrote: “The old boys are just about washed up and if Boudreau intends to make a pass at the pennant he might as well go all the way with the youth movement.…The Sox have done very well with their Lepcios, Whites, Gernerts, Brodowskis & Co. They did better than well when Piersall was with the club, sloughed off when he was disciplined.” And, “Do these Red Sox want to win? This telephone has been ringing all morning with the same fan query: ‘Have the Sox recalled Piersall yet?’ It seems they better had.”91

On July 14, Jim had another run-in with an umpire, this one during a Monday night home game that drew 10,200. Piersall argued that he caught a triple and was tossed for the third time since he joined the Barons. Jim admitted later that he did not catch the ball on the fly.92

As if this soap opera needed more subplots, this item appeared in the July 15 Boston Traveler: “Jim Piersall may come back to Boston in a Celtics’ basketball uniform before he returns to the Red Sox. Boston’s club in the National Basketball Association put Piersall on its negotiations list today. The Celtics now will attempt to sign him to play this winter.”93 However, GM Cronin immediately announced that the Red Sox would not give him permission to play even if he was interested in doing so.94

Piersall’s antics literally reached new heights July 16 in a home game with Atlanta. He squirted home plate with a water pistol to greet teammate Milt Bolling as he arrived following a homer. Shortly afterward, Jimmy argued loudly over a strike three call, causing his dismissal from a fourth contest. Jim then went to the Rickwood Field grandstand roof and continued to heckle the umpire.95

That was the last straw for President Hurth, who suspended Jim for three games and fined him $50. That was also the last straw for Joe Cronin, who summoned his troubled outfielder to Boston. The Associated Press article added, “There were unconfirmed reports that the…outfielder would not return to the Barons.”96 That possibility was substantiated the next day when it was learned that Jim had flown on a one-way ticket and that all his clothing and equipment followed him to Boston.97

A headline on the front page of the evening Boston Traveler on Friday, July 18, the day after Jim’s return, blared, “Piersall May Return To Lineup.” Reporters met with an “extremely nervous” Piersall at his home that morning as he waited to meet with Cronin. Concerning the possibility of his playing that night against Cleveland, Jim said, “The suspension stands in the big leagues as well as in the Southern Association, but I hope the Red Sox can do something about it and get it cut to one day.” He revealed that, at the insistence of Red Sox officials, he had visited “a nerve doctor” in Birmingham. According to Piersall, the doctor believed his nervous condition had been brought on by the uncertainty about whether he’d be playing in Birmingham or Boston. “He gave me some pills and told me, ‘I don’t think you need these, and you can do what you want with them, but they may relax you and slow you down a little.’ But I didn’t want to slow down any, and I threw them down the drain.” Jim admitted he didn’t like playing in Birmingham because of the heat but bragged that attendance tripled in his time with the club. He also gave his paranoid opinion of the Southern Association arbiters. “The umpires are out to get me down there….They’re strictly bush all the way.” He excused his outlandish behavior this way: “My jumping around out there put the fans on me…and it takes the pressure off the rest of the boys.” He boasted that he had not made an error during his three weeks with Birmingham. He also revealed that he had collected more than $600 worth of clothing from merchants who offered prizes for extra base hits and hitting certain signs in the park. Ever the optimist, Piersall said, “I’ve learned my lesson, and I’m ready to play up here.”98 He then went to a radio station for a live interview and took so many phone calls from fans that the show was extended 15 minutes.99

The meeting with Cronin turned out to be an automobile ride during which Joe gave his young farmhand “a fatherly talk.” All the GM would say afterward was, “Right now, he’s still on the Birmingham roster. In three or four days, I may tell you something different.” That statement set off speculation that Piersall could be sent to another Red Sox farm club or that Joe would intercede with Boudreau to get Jim back in a Red Sox uniform.100,101

None of that came to pass. After meeting with Jim Saturday morning and talking to owner Tom Yawkey, Cronin made a stunning announcement. “After consultation and with advice of doctors, Jim Piersall is going to take a rest. The ball club, of course, is interested primarily in Jim Piersall—not where he is going to play or how or what position.” Pressed for further comment, Cronin said, “I think it would be for the best interests of Jim Piersall if all of us left him completely alone for the time that he’ll be absent from baseball.” The Birmingham Barons placed Piersall on the disabled list.102

Jim acted as if a great weight had been removed from his shoulders. When he returned with his wife from the second meeting, “he was bubbling over with good spirits, singing in an off-key baritone…” according to a front-page story in the Boston American. He refused to add anything to what Cronin had said.103

After being examined at a private facility in Georgetown, Massachusetts, Piersall was admitted to Danvers (MA) State Hospital on July 22 for a 10-day observation period. The transfer was made with the consent of Jim’s wife after her husband became “overactive and very difficult to manage.” “He’s a pretty sick boy right now,” said Dr. Clarence Bonner, superintendent of the hospital. Jim’s condition was diagnosed as “nervous exhaustion.”104 The following day, he was transferred to Westborough State Hospital to be nearer his home in Newton.105

Jimmy wrote this about his 1952 season on the first page of Fear Strikes Out: “I don’t remember any of it. From the moment I walked into the lobby of the Sarasota-Terrace Hotel in Sarasota, Florida, to report to the Red Sox special training camp on the morning of January 15, 1952, until the moment I came to my senses in the violent room of the Westborough State Hospital in Massachusetts the following August, my mind is almost an absolute blank. I do have a clear recollection of the birth of my second daughter, Doreen, in March, but outside of that, there are only a few hazy impressions.… Shock treatments, faith, a wonderful wife, a fine doctor and loyal friends pulled me out of it.”106

Billy Martin had said in July that he had “no regrets” about fighting Piersall because “he had it coming.”107 But when the Yankees infielder learned of Jim’s illness, he felt ashamed. “I didn’t know he was sick like that. Maybe we deserve each other. Sometimes I think I’m ready for the guys with the white coats myself.”108

Jim disappeared from the newspapers for the entire month of August. Finally, an item appeared stating that Piersall, who “suffered a nervous breakdown,” returned to his Newton home on September 9. Although still in the “convalescing stage,” he was reported by the Red Sox front office “to be getting along very well.”109 Lou Boudreau expressed delight that Jim had improved enough to leave Westbrook hospital. “If Jim is well, I’m sure he’ll be one of our regular outfielders next season.…He’s a brilliant prospect.”110

In November, Piersall took his family to Sarasota for the winter to prepare for spring training 1953.111 In addition to paying all his medical bills, the Red Sox took care of his family’s expenses in Florida.112

As the Red Sox started spring training for the 1953 season, Boudreau announced that Piersall was his right fielder “if he is in as good shape physically and mentally as reported.”113

Jim rewarded his manager’s faith in him by batting .272 in 151 games that season. Modern defensive statistics rank him first among American League right fielders in 1953 in Total Zone Runs and Range Factor/Game.114

NEAL GOLDEN is a Catholic religious brother who has taught high school math and computer science at Brother Martin High School in New Orleans for over 50 years. He wrote the first high school computer programming text published in the United States in 1975. He has been a member of SABR for over 15 years. He is a lifelong Cardinals fan who publishes a baseball e-zine on his website: goldenrankings.com.

Notes

- sabr.org. Jim Piersall biography by Mark Armour.

- Murray Kramer, “Murphy Reveals Story Behind Red Sox Kids,” Boston American; May 11, 1952, 18.

- Joe Cashman, “Pesky Delighted with New Pact,” Boston American; March 2, 1952, 19.

- Anton Demers, “Lipon Over Piersall?–No!,” Boston American; July 14, 1952, 7.

- Larry Claflin, “Vern Capable of Replacing Ted in Left,” Boston American; March 18, 1952, 29.

- John Drohan, “Red vs. Sox in First Hose Intra Squad Tilt,” Boston Traveler; March 4, 1952, 42.

- Mike Gillooly, “Grade A Outfield Talent Brought Piersall Shift,” Boston American; March 4, 1952, 16.

- Boston Daily Record; March 10, 1952, 42.

- Ibid.

- Jim Piersall and Al Hirshberg, Fear Strikes Out: The Jim Piersall Story (New York, Open Road Integrated Media, 2011); Kindle location 947.

- Piersall and Hirshberg; Kindle location 1061.

- Ed Costello, “Dropo’s Bat Paces ‘Sox,’ 7–0,” Boston Herald; March 6, 1952, 22.

- Joe Cashman, “Senators Hand Hose 5th Loss in Row, 4 to 1,” Boston Daily Record; March 14, 1952, 11

- John Drohan, “Boudreau Still Testing With Piersall, Stephens,” Boston Traveler; March 14, 1952, 35.

- Joe Cashman, “Piersall and Parnell Sparkle But Sox Bow,” Boston Daily Record; March 15, 1952, 25.

- Boston Herald; March 16, 1952, 119.

- Joe Cashman, “Sox, Braves Rich in Talented Young Players,” Boston Daily Record; March 24, 1952, 7.

- Piersall and Hirshberg; Kindle location 947.

- Tommy Fitzgerald, “New Praise of Jim Piersall Hints Colonels May Get Him,” The Courier-Journal; March 30, 1952, 27.

- Ibid.

- Joe Cashman, “Piersall at Short Proves Revelation,” Boston Daily Record; April 5, 1952, 52.

- Ibid

- Joe Cashman, “3 Yearlings Terrific As Parnell Wins, 3–0,” Boston Daily Record; April 16, 1952, 37.

- Mike Gillooly, “Rizzuto Scores on Mize’s Single,” Boston American; April 24, 1952, 20.

- Boston Herald; June 6, 1952, 22.

- Arthur Sampson, “Sox Protest Involves Umpire’s Judgment, Unlikely to Get Far,” Boston Herald; May 12, 1952, 15.

- Mark Cofman, 162–0: Imagine a Red Sox Perfect Season: The Greatest Wins! (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2010); 81.

- Bill Pennington, Billy Martin: Baseball’s Flawed Genius (Boston and New York, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt: 2015); 86–87.

- Times-Picayune; May 25, 1952, 89. Martin’s fight with Piersall stirred up the slumbering Yankees. They won 13 of their next 18 games to climb into first place.

- Herb Raley, “Billy Martin, Jim Piersall fight at Red Sox-Yankees game,” Boston Globe, May 25, 1952, page unknown. Piersall often excused his behavior by saying that anyone would have done the same in his position.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Newport Daily News, May 27, 1952, 12.

- Ibid.

- Joe Cashman, “Piersall Chased,” Boston Daily Record; June 2,1952, 32.

- Boston Traveler; June 3, 1952, 50.

- Ed Costello, “Piersall Breaks Down, Cries After Walking Out on Meeting,” Boston Herald; June 4, 1952, 22.

- Ibid.

- Alan Frazer, “Tigers Ride Jim Piersall,” Boston American; June 9, 1952, 32. Ray sang the song “Cry” that topped the charts in 1952.

- Austen Lake, “Lou Wins Big Debate; Loses a Little One,” Boston American; June 9, 1952, 47.

- Will Cloney, “Red Sox Win 11-9, In Last of Ninth,” Boston Herald; June 12, 1952, 1.

- Springfield (MA) Union, June 29, 1952, 9.

- John Drohan, “Even White’s Slam Didn’t Dim Jim’s Antics,” Boston Traveler; June 12, 1952, 17.

- Joe Cashman, “Piersall Punishment Could Hurt Red Sox,” Boston Daily Record; June 17, 1952, 14.

- Bill Cunningham, “Don’t Give up Yet On Problem Boy, Psychiatrist Might Help Straighten Out Piersall,” Boston Herald; June 30, 1952, 12.

- Mike Gillooly, “Piersall .478 Against Tigers Yet Doesn’t Start in Detroit,” Boston Traveler; June 25, 1952, 30.

- Mike Gillooly, “Stunner! Red Sox Release Piersall,” Boston American; June 28, 1952, 4.

- Bill Cunningham, “Don’t Give up Yet On Problem Boy, Psychiatrist Might Help Straighten Out Piersall,” Boston Herald; June 30, 1952, 12.

- Mike Gillooly, “Stunner! Red Sox Release Piersall,” Boston American; June 28, 1952, 4.

- Al Blackman, “Piersall’s Trip to Barons Seems Disciplinary Move,” Times-Picayune; June 29, 1952, 84. The Red Sox were in 4th place, only 3½ games behind the first-place Yankees.

- Ibid

- Austen Lake, “Queer Case of Piersall: Cute or Quaint,” Boston American; June 30, 1952, 43.

- Ibid

- Peter Golenbock, Red Sox Nation: The Rich and Colorful History of the Boston Red Sox, (Chicago: Triumph Books: 2015); 202.

- Mike Gillooly, “Piersall’s Release Stunner,” Boston American; June 28, 1952, 8.

- Leo Monahan, “Sox Fans up in Arms as Kid Goes,” Boston American; June 29, 1952, 19.

- Boston American; June 30, 1952, 3.

- Austen Lake, “Queer Case of Piersall: Cute or Quaint,” Boston American; June 30, 1952, 43.

- Ibid.

- Piersall and Hirshberg; Kindle location 986.

- Boston Herald; July 4, 1952, 4.

- Ibid.

- Arkansas Democrat; July 17, 1952, 29.

- Ibid.

- Boston American; June 30, 1952, 31.

- Ibid.

- Boston American; July 3, 1952, 13.

- Ed Costello, “Piersall May Return If Batting Improves,” Boston Herald; July 4, 1952, 1.

- Ibid. Golenbock says in Red Sox Nation (page 202) that Piersall was accused of kicking the boy. However, none of the contemporary newspaper articles mention kicking, only spanking.

- Nick Del Ninno, “Piersall Ousted for Spanking Stephens Boy,” Boston Traveler; July 3, 1952, 10.

- Virginia Bohlin, “‘Spanking by Piersall Playful’—Mrs. Stephens,” Boston Traveler; July 3, 1952, 5.

- Nick Del Ninno, “Piersall Ousted for Spanking Stephens Boy,” Boston Traveler; July 3, 1952, 10.

- “Bob Dunbar,” Boston Herald; July 4, 1952, 4.

- Paul Whelton, “Piersall Wires Ronnie Regrets for Spanking,” Boston Daily Record; July 4, 1952, 4.

- Bill Keefe, “Pelicans Bow Before Barons for Second Straight Night, 8 to 4,” Times-Picayune; July 4, 1952, 8.

- Bill Keefe, “Barons Shade Pels, 3-2, in Rhubarb-Filled Tilt,” Times-Picayune; July 6, 1952, 66.

- Arthur Sampson, “Piersall Still the Clown at Birmingham,” Boston Herald; June 30, 1952, 13.

- Ibid

- Harry Martinez, “Sports from the Crow’s Nest,” Times-Picayune; July 6, 1952, 68.

- Bill Keefe, “Viewing the News,” Times-Picayune; July 5, 1952, 10.

- Bill Keefe, “Viewing the News,” Times-Picayune; July 7, 1952, 28. Most of Keefe’s commentary was reprinted in the July 13, 1952, issue of the Springfield (MA) Union.

- Tom Monahan, “Dykes, Lopez OK Piersall,” Boston Traveler; July 8, 1952, 30.

- Boston Daily Record; July 15, 1952, 17.

- Boston American; July 9, 1952, 6.

- Austen Lake, “Boudreau Nixes Piersall Plea,” Boston American; July 10, 1952, 5.

- Bill Keefe, “Viewing the News,” Times-Picayune; July 9, 1952, 20.

- Times-Picayune; July 13, 1952, 81.

- bostonsportsmedia.com/2009/06/23/excerpt-on-dave-egan.

- Dave Egan, “Colonel Blames Sox Old Guard: Urges Piersall Return to Hose,” Boston American; July 13, 1952, 9.

- Ibid.

- Anton Demers, “Lipon Over Piersall?-No!,” Boston American; July 14, 1952, 7.

- Arkansas Democrat; July 15, 1952, 28.

- Boston Traveler; July 15, 1952, 1.

- Ibid, 13. Piersall had also been an outstanding basketball player in high school.

- Huntsville Times, July 17, 1952, 1.

- Arkansas Democrat; July 18, 1952, 18.

- Boston American; July 18, 1952, 6.

- Harry Friedenberg, “Piersall May Return To Lineup,” Boston Traveler; July 18, 1952, 16.

- Boston American; July 19, 1952, 16.

- Ibid, 11.

- Boston Daily Record; July 19, 1952, 27.

- Harry Friedenberg, “Piersall May Return To Lineup,” Boston Traveler; July 18, 1952, 16.

- Boston American; July 20, 1952, 1.

- Boston American; July 22, 1952, 41.

- Times-Picayune; July 23, 1952, 24.

- Piersall and Hirshberg, Kindle location 9.

- Boston American; July 19, 1952, 2.

- Pennington; 87. Martin and Piersall eventually became lifelong friends. Jimmy told the New York Post in 1980: “I love Billy Martin. He helped me when I was down.” Of the fight, Piersall said, “It was just one of those things that happened in baseball back then. Neither of us held a grudge.”

- Boston Herald; September 11, 1952, 12.

- Boston Daily Record; September 12, 1952, 28.

- Ed Costello, “’I’m Ready,’ Says Piersall,” Boston Herald; November 9, 1952, 153.

- Golenbock; 203.

- Times-Picayune; December 3, 1952, 31.

- www.baseball-reference.com/players/p/piersji01.shtml.