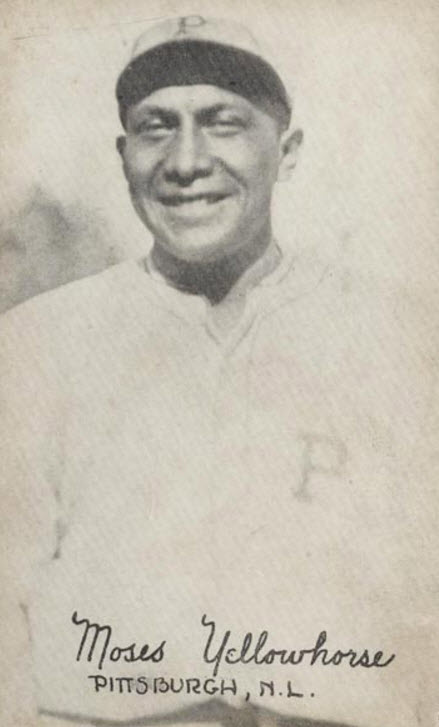

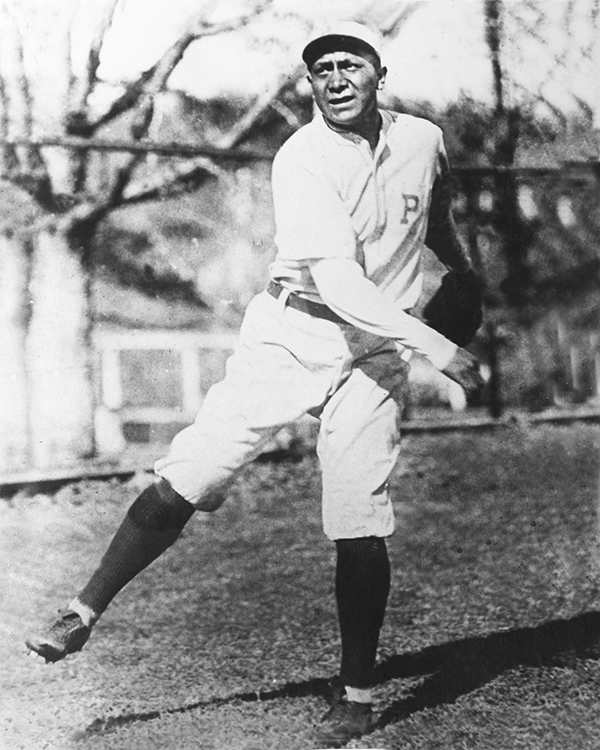

Moses Yellow Horse, Pittsburgh Pirate

This article was written by George Skornickel

This article was published in The National Pastime: Steel City Stories (Pittsburgh, 2018)

Moses Yellow Horse was 23 years old when he made his major league debut in 1921 with the Pittsburgh Pirates. Said to have been the first full-blooded Native American to play in the majors, the Pawnee may also have been the darkest-skinned major leaguer since the color line was drawn in the late 19th century. Certainly no big-leaguer before him had a name that sounded more Native American than Moses Yellow Horse. From Jim Thorpe and Chief Bender to Louis Sockalexis, who helped put the “Indian” in the Cleveland Indians, indigenous people had been sporadically represented on the rosters of major league teams since before World War I.

Moses attended the Federal Indian School at Chilocco, Oklahoma, where he honed his baseball skills by throwing stones at rabbits and squirrels for the cook pot. At the age of 19, in 1917, he was playing both varsity and semipro ball. By 1920, he helped pitch the Little Rock Travelers to the Southern Association championship with a record of 21 wins and 7 losses.

On September 16, Yellow Horse’s contract was purchased by the Pittsburgh Pirates. The Sporting News reported: “The sale of Moses Yellow Horse was rather un-expected, not that the Indian is not worthy of advancement, but it was generally expected that the young Pawnee would be allowed to spend another season here.”1 The Pawnee Chief’s writer wrote, “Yellow Horse is sure to make good. He is a close student and soaks up every ounce of information that is given in a wise manner. The Indian will keep National League batters swinging with one foot free when he is on the mound. He has terrific speed, but wonderful control of it. He also has a good curve ball and controls it equally as well as his fast one.”2

Later it was revealed that the purchase of Yellow Horse by the Pirates was a ruse to prevent his being drafted from Little Rock. The Pirates were to return him to the Travelers for the 1921 season, but Yellow Horse pitched so well in spring training that manager George Gibson insisted on keeping him for the season, whatever the price that might be asked for his release. Gibson’s judgment seemed justified. Yellow Horse demonstrated in his brief trials that he was worth it to a club that needed just one more winning pitcher to make it a pennant favorite.

Although Native people were not formally banned from baseball, Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss’s signing of Yellow Horse flew in the face of tradition. From time to time a few Native people—like Thorpe, Bender, and Chief Meyers—had made it to the majors, but because of their mixed ancestry, the color line had not been invoked.3 So how did Moses Yellow Horse, “as dark as the previous night’s lunar eclipse,” gain entry in the league?4

For one thing, Dreyfuss was a powerful force, and Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis was intrigued by Yellow Horse’s American Indian heritage.5 Landis’s fascination with Yellow Horse was so great that in the spring of Yellow Horse’s first season with the Pirates, the commissioner summoned manager Gibson and Yellow Horse to his chambers. After their meeting, highlighted by a question and answer session, Landis was impressed by the Pirates’ latest addition.6 Many newspapermen were impressed by him too. The Sporting News reported, “Fandom here has gone wild with Moses Yellow Horse, the young Indian slabman, who has been used to date only as a relief artist. They like the young Indian’s actions, and are convinced he is going to shine when given the right opportunity.”7

Other writers were mixed in their reviews. One anonymous scribe in the March 19 Sporting News wrote, “Pirates are comparing Moses Yellow Horse, the Indian pitcher Barney Dreyfuss brought from Little Rock, to Chief Bender. All he lacks is Bender’s size, stuff and disposition. He’s an Indian, with two legs and two arms, not a bad pitching prospect at that, however, but hardly a Bender.8

A Pittsburgh tradition was born with Yellow Horse’s penchant for successful relief pitching appearances. It wasn’t long before fans began to chant, “Put in Yellow Horse” whenever the starting pitcher faltered. The chant became so ingrained during his short career with Pittsburgh that it survived him by many years. Jim Nasium, a Sporting News writer, related in a 1926 column that during a lecture at the nearby University of Pittsburgh, a professor became lost in his notes, confused, and tongue-tied, and that his stammering was interrupted by a student who yelled, “Put in Yellow Horse.”9

In a July 5 game against the Cardinals, the 5-foot-10, 180-pound reliever suffered an arm injury that required surgery and shelved him for two months. His 5-3 record helped the Pirates finish in second place, four games behind the New York Giants. Had he been healthy, he might have significantly altered their finish, but he was sorely missed by the Pirates and the fans.

Because of his long layoff, Yellow Horse’s teammates voted him only a 2/5 share of their second-place money. Commissioner Landis overruled the decision and decreed him a full share.

Much blame for the failure to win the pennant was placed upon manager Gibson, who was accused of being unable to discipline his team. The press was rife with charges of heavy drinking against unnamed players. Bill McKechnie replaced Gibson as manager and Gibson warned McKechnie that he would have to keep an eye on roommates Yellow Horse and Rabbit Maranville. Maranville gave Yellow Horse the nickname Chief, and his first drink of whiskey.

Yellow Horse had insomnia and couldn’t sleep in hotel rooms. McKechnie, in a stroke of genius, decided the best way to keep an eye on his two problem children was to have them room with him. McKechnie would rent hotel suites with three beds, taking the third himself.

As Pat Harmon reported in the Cincinnati Post and Times Star:

The first night on the road, McKechnie entered the suite about 9 p.m. only to discover Yellow Horse and Maranville playing a game. They were standing on the window ledge, 16 stories above the ground, catching pigeons by scooping them off the ledge.

Maranville had made a bet with Yellow Horse that he could get more pigeons in fifteen minutes than Yellow Horse. Rabbit won 8-5. But the fun wasn’t over. McKechnie then opened a closet door. Out flew several pigeons. McKechnie immediately retreated and went to another closet to hang up his coat. “Don’t open the door,” Maranville warned. “The chief has his pigeons in there.” Following that incident, McKechnie got a room by himself.10

Dissatisfaction with Yellow Horse began to surface among Pirates fans after he got injured and had surgery. His drinking problem had also become well known. An October newspaper account predicted that “as a pitcher and player his days are few.” Sadly, this was the same paper that earlier in the year had touted him the “best all-round player.”11 Yellow Horse was not meeting the expectations of the owners, either. He did little to dispel stereotypes about Native Americans with his drinking and disruptive behavior

Dissatisfaction with Yellow Horse began to surface among Pirates fans after he got injured and had surgery. His drinking problem had also become well known. An October newspaper account predicted that “as a pitcher and player his days are few.” Sadly, this was the same paper that earlier in the year had touted him the “best all-round player.”11 Yellow Horse was not meeting the expectations of the owners, either. He did little to dispel stereotypes about Native Americans with his drinking and disruptive behavior

Years later, Tribal leader Earl Chapman told of Yellow Horse drinking during the Pirates’ 1922 games. Not in the bullpen, but while he was pitching. According to Chapman’s tale, Yellow Horse would signal the Pittsburgh groundskeeper that the mound needed more dirt. The groundskeeper would then come out and put shots of whiskey all around the mound. Yellow Horse would then sneak shots without anybody noticing and—if you believe Chapman’s tale—he never got caught.12

Yellow Horse’s effectiveness both as a pitcher and a crowd pleaser waned as the 1922 season wore on. Alcohol had a definite deleterious effect on his performance. Both Dreyfuss and McKechnie were disheartened. Healthy except for a bout with tonsillitis that cost him a few weeks in early August, Yellow Horse appeared in 28 games for Pittsburgh in 1922, all but four of them in relief. He compiled a 3–1 record and a 4.52 ERA.

In December, Yellow Horse was traded along with three other players and $7,500 to the Sacramento Senators of the Pacific Coast League for pitching phenom Earl Kuns. The trade to Sacramento meant the end of Yellow Horse’s career in the major leagues.

He played sporadically in the minors over the next two years. In 1923, as the ace of the pitching staff, he helped the Senators to a second-place finish. He ended the season with a 22-13 record and an ERA of 3.68.

Yellow Horse injured his arm midway through the 1924 season. Other than a few games in 1926, that was the end of his time in Organized Baseball. At the age of 28, he returned home to Pawnee, Oklahoma.

Yellow Horse was a barely functional alcoholic until 1945. He then spent time and energy with tribal concerns. He helped establish and coached in youth baseball, umpired for semipro games, and pitched from time to time. Much of his time was spent teaching Pawnee traditions, ceremonies, and language, which were disappearing. Yellow Horse never abandoned his Pawnee heritage.13

In 1935, a character based on Yellow Horse appeared in the comic strip Dick Tracy. Cartoonist Chester Gould,who also grew up in Pawnee, always included aspects of his hometown in the comic. Yellow Pony was a hero who helped capture Boris and Zora Arson, two escaped convicts. His character, however, was portrayed in a racist manner, speaking in guttural, grunting, English. Initially introduced as a naive character, Yellow Pony developed into an ardent crime fighter, shooting villains and helping Tracy plot the capture of various criminals.

Moses Yellow Horse “thought Yellow Pony was funny” and the portrayal, he said, “wasn’t a big deal.”14

GEORGE SKORNICKEL is a retired educator who has been a Pirates fan for over 60 years. He is the president of the Forbes Field Chapter and has presented at SABR 44 in Houston and SABR 45 in Chicago, Jerry Malloy Negro League Conference in 2012 and 2014, the Frederick Ivor-Campbell 19th Century Baseball Conference in 2017, and the Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture in 2017 and 2018. He has been published in the “Baseball Research Journal” and Sweet ’60: The 1960 Pittsburgh Pirates, and is the author of “Beat ’Em Bucs: The 1960 Pittsburgh Pirates.” He lives outside of Pittsburgh in Fawn Township with his wife Kathy and two Labs, Maz and Dexter.

Notes

- Sporting News, September 16, 1921.

- “Pirates Pawnee pitcher went ‘way of all bad Injuns,” Sports Collectors Digest, March 4, 1994:60.

- William Jakub, “Moses Yellow Horse: The Tragic Career of a Pittsburgh Pirate,” Pittsburgh History, Winter, 1995/96.

- Todd Fuller, “60 Feet Six Inches And Other Distances from Home,” (Saint Paul: Holy Cow! Press, 2002), 142.

- “Mose J. Yellow Horse, Pawnee baseball player,” AAA Native Arts, https://www.aaanativearts.com/mose-j-Yellow Horse-pawnee-baseball-player.

- Pittsburgh Gazette, April 21, 1921.

- Pittsburgh Gazette, April 21, 1921.

- Sporting News, March 19, 1921.

- Sporting News, March 19, 1921.

- Pat Harmon, “Chief Yellow Horse and the Rabbit,” Cincinnati Post & Times-Star, April 24, 1964.

- Jim Nasium, Sporting News, 1926.

- Harmon, “Chief Yellow Horse and the Rabbit.”

- Fuller, “60 Feet Six Inches,” 54.

- Jakub, “Moses Yellow Horse.”