‘Our Lady Reporter’: Introducing Some Women Baseball Writers, 1900–30

This article was written by Donna L. Halper

This article was published in Fall 2019 Baseball Research Journal

In 1763, literary critic Dr. Samuel Johnson said about women preachers, “Sir, a woman’s preaching is like a dog’s walking on his hind legs. It is not done well; but you are surprised to find it done at all.”1 In the early 1900s, that same attitude prevailed when it came to women sports journalists: male editors and readers did not expect it to be done well and were surprised to find it being done at all.

In 1763, literary critic Dr. Samuel Johnson said about women preachers, “Sir, a woman’s preaching is like a dog’s walking on his hind legs. It is not done well; but you are surprised to find it done at all.”1 In the early 1900s, that same attitude prevailed when it came to women sports journalists: male editors and readers did not expect it to be done well and were surprised to find it being done at all.

Stereotypical beliefs about women permeated American popular culture. Newspaper articles claimed that women “autoists” (drivers) were a danger on the road.2 As one magistrate stated in 1915, “In my opinion, no woman should be allowed to operate an automobile.”3 Another common belief was that women would be horrified by hearing even the mildest profanity. This was the rationale for discouraging women from entering law, because they might hear bad language in the court room.4 Women were supposedly driven by unhealthy curiosity, like Eve in the Bible and Pandora in Greek mythology. And it was widely believed that the female brain was not equipped for understanding complex subjects like mathematics or politics; psychologist Gustave Le Bon, writing in 1895, compared women’s intellectual capacity with that of children.5 Women’s allegedly limited brainpower, and their lack of common sense, was a staple of comedy: one of the most common roles reserved for female comics in vaudeville was the “Dumb Dora,” a woman who was scatter-brained, vapid, and frequently illogical.6

One other common stereotype was that women hated sports. If they attended a game, it was only to make their boyfriend or husband happy, and if they were single, they would only come to the ballpark because they hoped to get a date with a player. A popular 1911 cartoon by Gene Carr called “Flirting Flora” reflected this belief. It depicted a stylish young woman who flirted with several ballplayers simultaneously, getting them to compete for her affection.7 Meanwhile, the idea that women were not intelligent enough to comprehend the rules of baseball was promulgated by numerous anecdotes in newspapers, telling of an unnamed female reporter who covered a ballgame though she had no idea what an umpire was, or the one who asked incredibly stupid questions of the players, or the society woman who sat through a game despite having no idea who the teams were.

Of course, there might be the occasional woman who knew something about baseball, of course because her husband had taught her: for example, L.W. Bloom, editor of the Concordia (KS) Empire, wrote a 1910 opinion piece praising Gertrude (Mrs. Earl) Brown, Concordia’s biggest female fan, for her thorough knowledge of the game; she could even use a scorecard as well as her husband did. But such a woman was considered unique in Bloom’s estimation, because “Most women do not understand a hit from a foul ball.”8

But in many cities, reporters were noticing a growing number of “lady baseball fans.” One New Brunswick (NJ) newspaper wrote in 1910 that there were as many female fans in that city as male ones, and that young women were so interested in baseball that the local high school was organizing an all-female team.9 In Buffalo, the sports editor commented that in 1900 hardly any women attended the games, but only five years later, thousands of women were in attendance, many of whom could score the games and were joining in debates about whether a certain play should be a hit or an error.10 And in Oakland, a woman reporter who observed an increase in female fans at the ballpark wrote they had become “a distinct factor in the summing up of the gate receipts for the season.”11 It is also worth noting that the song “Take Me Out to the Ball Game,” which centers on the persona of a female fan, was written in 1908.12

However, while the evidence points to the number of female fans increasing, most of the fans were male, and not all were happy about women coming out to the ballpark. Some owners believed that the presence of women would be “civilizing” and result in less cursing or bad behavior from the athletes.13 But baseball was presented as a pastime for men and boys, and though female fans might be tolerated (often with some amusement), the sport “provided male audiences with empowering images of manhood.”14 The ballpark was thus a masculine domain where male fans and masculine behaviors were the norm. Perhaps as a reaction to more female fans attending games, stories began to appear in the newspapers about the (allegedly) strange behavior of these women, such as the nameless young lady who got so upset when the boy sitting next to her made a negative comment about her team that she jabbed him with her hatpin.15

Nearly all news and sports reporters of the early 1900s were male, as were their editors, who geared their coverage to the male reader. As such, sending a woman who usually wrote about fashion and homemaking to cover a ballgame from the “feminine point of view” was considered a jolly gimmick. The headline would often mention the “lady reporter.” Readers might see headlines like this one, promoting some unique interviews about the 1912 World Series: “The heroes of the coming big baseball game personally sized up and interviewed BY A WOMAN.”16 (And no, I did not add the capital letters.) Since women were presumed to know little about the game itself, a female reporter was expected to write a human interest story — this headline, also from 1912, was typical: “She’s Going to Write About the Personality of Five Baseball Heroes.”17 Both headlines topped syndicated articles by Idah McGlone Gibson, an experienced female columnist who absolutely did know something about baseball, but perhaps the headline writers assumed she was just another “Dumb Dora.”

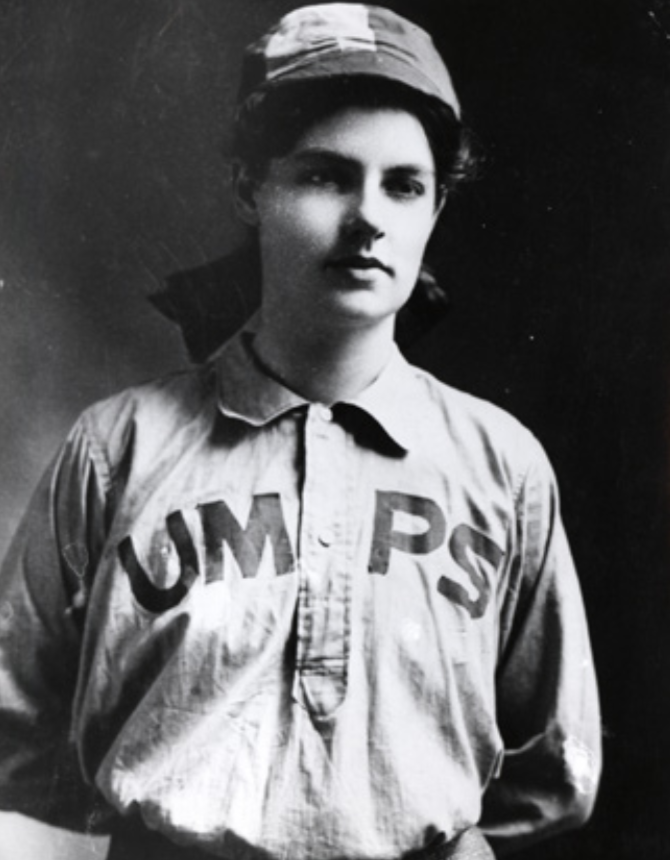

Despite stereotyping, a few young women of that era had successful careers that involved baseball. From about 1905 to 1911, Amanda Clement umpired college and semi-pro games in South Dakota and several neighboring states. She was widely respected and praised for her accuracy; one reporter noted that “she knows her business…” and that she “seldom makes a mistake.”18 In 1911, Helene Hathaway Robison Britton became the owner of the St. Louis Cardinals, the first woman to own a professional sports team; she remained owner for seven years.19 And the earliest female sportswriter we know about goes back to 1890 — the possibly pseudonymous Ella Black, a Pittsburgh reporter who covered baseball for Sporting Life.20 A few other pioneering women were soon to follow.

Despite stereotyping, a few young women of that era had successful careers that involved baseball. From about 1905 to 1911, Amanda Clement umpired college and semi-pro games in South Dakota and several neighboring states. She was widely respected and praised for her accuracy; one reporter noted that “she knows her business…” and that she “seldom makes a mistake.”18 In 1911, Helene Hathaway Robison Britton became the owner of the St. Louis Cardinals, the first woman to own a professional sports team; she remained owner for seven years.19 And the earliest female sportswriter we know about goes back to 1890 — the possibly pseudonymous Ella Black, a Pittsburgh reporter who covered baseball for Sporting Life.20 A few other pioneering women were soon to follow.

In Trinidad, Colorado, from about 1905 to 1910, Ina Eloise Young wrote about baseball for her local newspaper, the Trinidad Chronicle-News. She even became the newspaper’s sports editor, highly unusual for a woman of that era. And after marrying in 1910, she and her husband settled in Denver where — using her married name, Ina Young Kelley — she covered sports for the Denver Post for another year and a half. Like umpire Amanda Clement, Ina’s work was not seen as a gimmick and she was taken seriously by her male colleagues.21

Ina’s first beat was current events — she covered everything from forest fires to labor strikes to the Fourth of July parade. Trinidad had no minor league team, but semi-pro baseball was very popular, and the newspaper covered it faithfully. The local nine was called the Trinidad Big Six (named for a bar-and-grill that was one of the team’s sponsors), and until the 1905 season, a male reporter wrote about their games. But when he left, the Chronicle-News had no baseball expert, no one who even knew how to keep score. Luckily, Ina’s dad and her youngest brother were big fans; and her brother showed her how to use a scorecard.22 That was enough to land a job in the sports department.

Ina became a bylined reporter in 1907 — unusual for anyone, male or female back then, when only a newspaper’s biggest names got a byline. She was also promoted to “sporting editor,” as sports editors were then known. She covered Denver Grizzlies minor league baseball as well as local games in the Trinidad area, and in 1908 she covered the World Series.23 When profiling her, journalism magazine The Editor and Publisher said she was the only female sporting editor in the United States.24 Ina’s in-depth knowledge of baseball helped her to win over even the most skeptical of her male colleagues — one of whom, the Boston Globe’s Tim Murnane, was a former pro baseball player and among the best-known sportswriters of that era. He was so impressed with her reporting skills that he praised her in one of his syndicated columns, noting that “Miss Young proved an excellent scorer, was familiar with every inside play, and surprised me with her knowledge of the game.”25 Murnane nominated her for an honorary membership in the newly formed Baseball Writers Association in 1908.26

By accounts from the newspapers of her day, Ina was treated like any other reporter during her seven years of covering baseball: she sat in the press box, she interviewed players and managers, and once the initial surprise at seeing a “lady reporter” wore off, her male colleagues seemed to accept her, as did the players.27 We may never know why she was such an exception, however. Few, if any, women of that time became reporters on the sports beat. Decades later, women sportswriters were treated as either curiosities or interlopers: for example, in 1941, Pearl Kroll — then a sportswriter for Time — found herself excluded from the press box; she was also expected to pay her own way when attending the spring training games she was covering.28

But despite the acceptance and praise Ina received, she sometimes had to fend off editors who wanted her to write articles for the society page. She also had to remind male sportswriters at other newspapers that not all fans (nor all readers of that publication) were male, as she did in a 1908 letter to the editor of Sporting Life.29 And while Ina had been in the right place with the right expertise, a major limitation for other women of her era was that women reporters were rarely trained to cover sports — not even women’s sports, which were neither as common nor as popular as they are today. Women were discouraged from participating in athletics, ostensibly because it was too strenuous, and because of the cultural belief that girls who took part in sports would become masculinized.30 Women journalists were expected to focus on “feminine” topics like cooking, fashion, music, and the comings and goings of members of high society. Women could become editors, but only of the “women’s page.”31 Some journalism schools even refused to admit them, including the Pulitzer School of Journalism at Columbia University.32

When a few women tried to write about sports, the reaction they got was often negative. As far back as 1901, certain male baseball writers expressed their annoyance about women who wanted to be taken seriously as reporters. Pseudonymous Buffalo sportswriter “Hotspur” (real name: Edward McBride) referred to them as the “squaws of the pencil.” As an example of why women sports reporters deserved such derision, he told the story of an unnamed woman reporter who got an interview with then-college pitcher Chris (Christy) Mathewson. While Hotspur seemed to feel the woman asked foolish questions and wasted Mathewson’s time, the young pitcher seemed pleased with their conversation; in fact, the questions she asked got him talking about himself in a way that gave readers more insight into Mathewson as a person. Readers learned his favorite subject in college was natural history, he never drank anything stronger than milk, and would not play on the Sabbath. In the interview Mathewson admitted he was embarrassed by the adulation he was receiving — especially from female fans.33 The interview was reprinted by the Denver Post a few days later, which mocked the player as much as the interviewer: while noting that Mathewson had “allowed” a “lady reporter” to interview him, sports editor Otto C. Floto observed that if the young man’s answers were truthful, he was a perfect human being who belonged in heaven, since he was much too good for this world.34

Some of the women reporters seemed to accept the negative reaction they received and the the jests that came their way. Some admitted they were not baseball experts (even if, as it turned out, they really did know a lot about the game), and apologized for any mistakes they might make. But women sports reporters developed their own strategies for winning over readers in that era. For some, using humor was effective — they showed they could not only take a joke but make some jokes of their own.

One good example of trying the humorous approach was Vella (Alberta) Winner, a women’s page reporter for the Portland (OR) Daily Journal. In April 1915, she wrote a piece about her impressions of the Portland Beavers’ home opener. She first reassured readers that she did know what a pitcher was, and she even knew the names of the players — and in the course of her article, she mocked some of the baseball clichés that men sportswriters overused. She then moved directly into commenting on some of the plays, as any male sportswriter would. But she also commented on who was at the ballpark — despite the rainy day, about 10,000 people were in attendance. And she observed that team owner Walter McCredie and his wife were watching the game; she talked to Mrs. McCredie, who seemed to be quite a fan, telling the reporter, “I never miss a game…I can keep just as good a box score as my husband.” Vella also noted that all the Portland fans sincerely believed the home team would have won, if only the weather had been better.35

Another woman who used humor when covering a game was Bertha “Bee” Hempstead, a women’s page, education, and features writer for the Topeka (KS) State Journal, who offered her observations about a minor league contest between Topeka and Denver in July 1915. While noting that the game itself didn’t give hometown fans much to cheer about, Hempstead employed the style that Vella Winner and other society writers used, commenting on the sights, sounds, and interesting people in the crowd: a local merchant who never missed a game, a group of salesmen for the Curtis Publishing Company who had won a contest and several female fans who were remarking on which players were the cutest. She also noted with dismay that Denver’s first baseman was wearing torn stockings.36

A tactic used by well-known St. Louis Republic society and gossip columnist “Serena Lamb” (a pseudonym for Lucy Stoughton) was self-effacement. When talking to a ballplayer, she would claim to know very little about the game, and then ask questions that any good interviewer, male or female, would ask. In July 1900, she interviewed several Cardinals’ ballplayers: outfielder Emmet Heidrick, who was recovering from a leg injury, and third-baseman John “Muggsy” McGraw. (Newspapers then spelled his nickname with two g’s; years later, it was spelled with only one.) To open the interviews, she acknowledged — perhaps with some sarcasm — that she was a “mere woman” and that those seeking in-depth analysis of yesterday’s game should seek out the “sporting columns.”37 Lamb’s goal was to provide her readers with personal insights into the players. Her style was conversational, and in both interviews, readers learned some interesting “fun facts” about the players — for example, Heidrick’s favorite color was blue, he had a large collection of silk ties, and he didn’t seem to have a girlfriend (at least not one that he would talk about).38 McGraw said he hated the nickname “Muggsy” and refused to answer to it, and he was also a world traveler, who had visited Cuba, South America, and parts of Europe.39

Male sports writers were not expected to write about the emotions or personality quirks of players. The sports pages focused on box scores and statistics, and the story was about who won, who lost, who played well, and who did not. Unlike the aforementioned Ina Eloise Young who typically wrote the way the men did — discussing the game’s most impressive plays or questioning a decision the manager made40 — societal expectations left fertile ground to be tilled by female reporters.

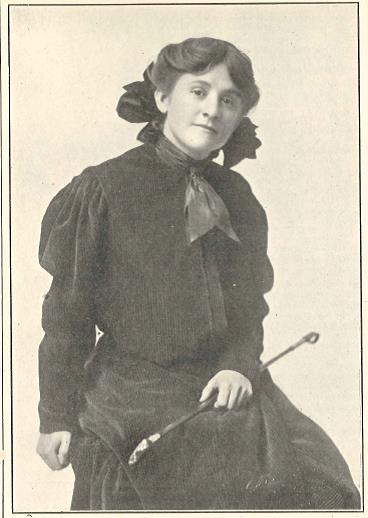

And that brings us back to Idah McGlone Gibson. Of all the women who ventured from the women’s page into sports reporting, she seems to have gotten the most respect, and with good reason: she was a nationally-known reporter and syndicated columnist, whose work appeared in both newspapers and magazines during the 1910s and 1920s. While she is all but forgotten today, a quick database search for her name on Newspapers.com gives more than 1,800 results in hundreds of old newspapers. Her career began in Toledo, Ohio, where she was a theater critic and then the society editor for the Toledo Blade. She later moved to Chicago, where she wrote about celebrities, dispensed household and relationship tips, and (as was often expected of female journalists) offered a “women’s perspective” on current events in her syndicated columns for The Day Book and other newspapers. Idah was among the first to profile the wives of presidents. While today we take this for granted, in her era, a president’s wife (the term “First Lady” was not yet in common use) was expected to stay in the background — in fact, there was an unofficial rule that she could not be quoted directly.41 Idah visited with four presidents’ wives, learning about their day-to-day activities. Her focus was always on what made each woman unique, rather than their status as wives of famous men.42 Given her ability to get interviews with a wide range of famous people, it is not surprising that the editor of The Day Book asked Idah to provide readers with the so-called “woman’s perspective” on the 1912 World Series — to discuss the personalities of the players and show these men “in a new light — as a woman sees a popular hero.”43 Because the women’s page writers did not have to observe the same parameters as the male baseball writers did, their profiles of players often brought out entirely different information because these profiles were aimed at female readers.

And that brings us back to Idah McGlone Gibson. Of all the women who ventured from the women’s page into sports reporting, she seems to have gotten the most respect, and with good reason: she was a nationally-known reporter and syndicated columnist, whose work appeared in both newspapers and magazines during the 1910s and 1920s. While she is all but forgotten today, a quick database search for her name on Newspapers.com gives more than 1,800 results in hundreds of old newspapers. Her career began in Toledo, Ohio, where she was a theater critic and then the society editor for the Toledo Blade. She later moved to Chicago, where she wrote about celebrities, dispensed household and relationship tips, and (as was often expected of female journalists) offered a “women’s perspective” on current events in her syndicated columns for The Day Book and other newspapers. Idah was among the first to profile the wives of presidents. While today we take this for granted, in her era, a president’s wife (the term “First Lady” was not yet in common use) was expected to stay in the background — in fact, there was an unofficial rule that she could not be quoted directly.41 Idah visited with four presidents’ wives, learning about their day-to-day activities. Her focus was always on what made each woman unique, rather than their status as wives of famous men.42 Given her ability to get interviews with a wide range of famous people, it is not surprising that the editor of The Day Book asked Idah to provide readers with the so-called “woman’s perspective” on the 1912 World Series — to discuss the personalities of the players and show these men “in a new light — as a woman sees a popular hero.”43 Because the women’s page writers did not have to observe the same parameters as the male baseball writers did, their profiles of players often brought out entirely different information because these profiles were aimed at female readers.

Not all newspapers that carried Idah’s work ran the interviews in the same order, but they appeared in publications from coast to coast, and some newspapers did place them on the sports page.44 In her interview with Red Sox manager Jake Stahl, they discussed, among other things, why he wasn’t called Garland (his real first name); how he got his nickname; his off-season job in banking, and of course, what his predictions were for the Series. When she talked to the Giants’ Christy Mathewson, he praised baseball as a great career for any college graduate — and Idah was impressed with his cultured and articulate way of communicating. They also talked about his approach to pitching, and how he had maintained his success for such a long time. (But he refused to make any predictions about the Series.) When she spoke to Red Sox star pitcher Joe Wood, her impression was that he was very level-headed and mature for someone only twenty-two; he asserted that he never drank liquor, nor even coffee or tea during the season, and he said he also tried to be careful about not eating too much, as he had seen other players have their careers shortened by not taking care of themselves. Several of Wood’s teammates jokingly wanted Idah to ask him about all the love letters he got from female fans; when she did, Wood expressed puzzlement that female fans had crushes on ballplayers, and he said he didn’t respond to the letters, which undoubtedly disappointed the young women who sent them.45

She had a brief interview with John “Muggsy” McGraw, who had been the Giants’ manager since 1902; McGraw evidently was willing to talk to female reporters — as you may recall, ‘Serena Lamb” had sat down with him back in 1900. Now, twelve years later, Idah noted that he seemed very serious; he told her he seldom liked to smile, not even when being photographed. While courteous, he did not appear very happy to be interviewed that day. Since she was a society columnist, Idah asked him about the rumors that pitcher Rube Marquard was set to marry vaudeville star Shirley Kellogg (some sources said he had already married), but McGraw demurred, saying he never commented on players’ personal lives. He did express satisfaction with his pitching staff over all. (Idah had her doubts and predicted Boston to win the World Series.46 She would be right.)

She also had a brief but cordial meeting with Charles “Jeff” Tesreau. An up-and-coming pitcher on the Giants, he was already very popular with the fans, many of whom hung around the Polo Grounds after the games, hoping to meet him and get an autograph. His key pitch, he told Idah, was the spitter (which was still legal in 1912) that McGraw and Mathewson had encouraged him to use.47 Given the number of big-name players who agreed to talk with her, we may assume that Idah’s presence at the ballpark was not treated like a stunt.

In 1916, Idah did some additional baseball interviews, beginning with Wilbert Robinson, manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers. The article started off with an amusing anecdote: when she came to the ballpark, Idah was stopped by someone who told her no ladies were permitted to watch the team practicing. But someone else said she could go in, because “She ain’t no lady. She’s a newspaper reporter.”48 She also interviewed Philadelphia pitching star Grover Cleveland Alexander (who wasn’t in the World Series, but she wished he were), and then chatted with Brooklyn outfielder Zack “Buck” Wheat. Unlike some players, Wheat seemed very shy about being interviewed, even when Idah asked him baseball questions. He did tell her that his wife had never seen a ballgame till they married, and now she was a big fan; he also spoke about the positive effect marriage had on him and surprised Idah when he stated that “a ball player never amounts to much until he marries.”49

In October 1917, she revisited John McGraw, who didn’t seem any more eager to be interviewed by Idah than he had been in 1912. They discussed how a manager handles temperamental players. While he didn’t want to name his most temperamental player, McGraw did single out the player he considered the least temperamental: Christy Mathewson.50 But in nearly every story, the fact that Idah was a “woman reporter” or a “lady reporter” was still somewhere in the headline.51

Society changed for women in many ways during the 1920s. Women got the right to vote, and radio made its debut: by the end of the decade, Lou Henry (Mrs. Herbert) Hoover became the first First Lady to give a radio talk (and yes, the term “first lady” had come into common use).52 More middle-class women were attending college, and there were more career opportunities open to them. And yet, some things did not change. The belief persisted that women were not knowledgeable about baseball and that women only attended games either because a male family member dragged them along or because they hoped to date a ballplayer. Novelist and reporter Katharine Brush, who wasn’t seeking a husband (she already had one) and who did know something about baseball, became a correspondent for her local newspaper, the Liverpool (OH) Review-Tribune. She covered the 1925 World Series between the Pittsburgh Pirates and the Washington Nationals.

In Pittsburgh, she noted that she was the only woman reporter in the press headquarters, which caused most of the men to look at her as if she had wandered into the wrong place.53 She also commented that many men she knew were not pleased when they met a woman fan who wanted to talk baseball; they were certain she couldn’t possibly know what she was talking about… proving dismissive attitudes from 1900 were still around in 1925. Brush was undaunted and proceeded to cover the Series again in 1926; in both years, she wrote about the games, but also discussed the wives of the players, chatted with interesting fans, and even talked to a couple of the men covering the game for their newspapers. And she often observed an unspoken attitude from her male colleagues that she would be better off sticking to the women’s page. (In fact, her editor told her to only write human interest pieces and not discuss what happened during the games.54)

Whether they were sent by male editors who thought a “woman’s perspective” on baseball might be entertaining, or they just wanted to prove they could cover baseball as well as a man, the female reporters of the early 1900s found different ways to navigate the obstacles put in their path. Baseball researchers have seldom examined their work, and few baseball history books have even acknowledged their existence until recently. (Also making it difficult to evaluate their efforts: some male reporters criticized them but did not tell us their names.55) Even though they were not beat reporters, there is still much more to learn about how these women (and those in the 1930s and 1940s) tried to redefine a woman’s place in sports journalism, long before the Women’s Movement made it easier for women to have non-traditional careers. I hope I have made a good start in introducing you to a few women who were determined to write about baseball, despite living in an era when they were discouraged from doing so.

DONNA L. HALPER, PhD, is a media historian, author of six books and many articles (including chapters in a number of SABR books). A former broadcaster and journalist, she is an Associate Professor of Communication and Media Studies at Lesley University in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Notes

1 Quoted in James Boswell’s 1844 edition of The Life of Samuel Johnson, 205-206.

2“Women Autoists Being Watched by Police,” Lincoln (NE) Star, August 12, 1913, 1.

3 “Against Women Autoists,” New York Times, September 3, 1915, 9.

4 Mary Jane Mossman, The First Women Lawyers: A Comparative Study of Gender, Law and the Legal Professions, Bloomsbury, 2006, 48-49.

5 Quoted in Gina Rippon, The Gendered Brain, Pantheon, 2019, 3.

6 Horowitz, Susan, Queens of Comedy: Lucille Ball, Phyllis Diller, Carol Burnett, Joan Rivers, and the New Generation of Funny Women, (New York, Routledge, 1997), 110-112.

7 Gene Carr, “Flirting Flora: Shortstop Shorty Gets a Jolt,” Denver Post, July 1, 1911, 6.

8 L.W. Bloom, “A Real Fan,” Concordia (KS) Empire, July 7, 1910, 2.

9 “High School Girls Practice Baseball,” (New Brunswick) Central New Jersey Home News, April 7, 1910, 6.

10 “The Anvil Chorus,” Buffalo Enquirer, January 25, 1905, 10.

11 Lynn Ethel Wilson, “She Is A Peculiar Species, The Female Baseball Fan.” Oakland Tribune, May 29, 1910, B7.

12 Jennifer Ring, Stolen Bases: Why American Girls Don’t Play Baseball, University of Illinois Press, 2009, 28.

13 John Thorn, Baseball in the Garden of Eden, Simon & Schuster, 2011, 88.

14 Michael Kimmel, qtd in John Bloom, A House of Cards: Baseball Card Collecting and Popular Culture, University of Minnesota Press, 1997, 101.

15 “Female Baseball Fan Jabs Boy With Hatpin,” Sioux Falls (SD) Argus-Leader, July 15, 1910, 1.

16 Advertisement in the Pittsburgh Press, October 2, 1912, 18.

17 Advertisement in (Chicago IL) The Day Book, October 2, 1912, 9.

18 “S. Dakota Has Woman Umpire,” Buffalo Times, June 2, 1906, 8.

19 Joan Thomas, Baseball’s First Lady, Reedy Press, 2010.

20 Scott D. Peterson, Reporting Baseball’s Sensational Season of 1890, McFarland, 2015, 38.

21 “Woman Sport Editor at the World Series,” Pittsburgh Press, October 14, 1908, 8.

22 “She’s Sporting Editor,” The Editor and Publisher, December 21, 1907, 11.

23 “This Colorado Girl is an Authority on All Sports,” Brownwood (TX) Daily Bulletin, January 6, 1910, 2.

24 “She’s Sporting Editor,” The Editor and Publisher, December 21, 1907, 11.

25 “How Miss Young Looked to Tim.” Trinidad (CO) Chronicle-News, October 20, 1908, 6.

26 Ina Eloise Young, “Sporting Writer of this Paper Tells of Final Game,” Trinidad (CO) Chronicle-News, October 17, 1908, 1, 9.

27 Ina Eloise Young, interviewed by A.H.C. Mitchell, quoted in “Women Should Be Editors of Sport,” Trinidad (CO) Chronicle-News, November 7, 1908, 3.

28 Bob Considine, “Blank Contract Sent Grove by Tom Yawkey,” (Scranton PA) The Scrantonian, March 9, 1941, 26.

29 Ina Eloise Young, “A Feminine Tribute,” Sporting Life, March 28, 1908, 6.

30 June A. Kennard, “The History of Physical Education,” Signs, (Vol. 2, No. 4, Summer, 1977), 841.

31 “Women in Journalism,” Brooklyn (NY) Daily Eagle, May 5, 1911, P4.

32 “No Women in the School for Journalism,” Vicksburg (MS) Evening Post, March 21, 1912, 4.

33 Hotspur, “Too Nice for his Little Job,” Buffalo Enquirer, May 16, 1901, 4.

34 Otto C. Floto, “Denver Team Loses — The Same Old Story,” Denver Post, May 19, 1901, 18.

35 Vella Winner, “Lady Reporter Takes in the Opener and is Impressed with What’s Going On,” Portland (OR) Daily Journal, April 14, 1915, 11.

36 Bertha Hempstead, “Thru Female Eyes,” Topeka (KS) State Journal, July 24, 1915, 4.

37 Serena Lamb, “Muggsy McGraw, Ball-Player and Actor,” St. Louis Republic, June 15, 1900, 30.

38 Serena Lamb, “Mr. Emmet Heidrick and His Necktie Fad: A Visit to a Baseball Favorite,” St. Louis Republic, July 29, 1900, 31.

39 Serena Lamb, “Muggsy McGraw, Ball-Player and Actor,” St. Louis Republic, June 15, 1900, 30.

40 At times, Ina did note something interesting from the crowd: during her World Series coverage in 1908, she remarked that the wives of the Cubs players were especially enthusiastic — they carried large Cubs banners and sometimes tooted horns in support of their team. Ina Eloise Young. “Miss Young Tells of Scenes and Incidents in Detroit Game,” Trinidad (CO) Chronicle-News, October 16, 1908, 3.

41 Idah McGlone Gibson, “The President’s Wife — Mrs. Taft As A Woman Sees Her,” Wilkes-Barre (PA) Times-Leader, October 29, 1912, 10.

42 For example, Idah McGlone Gibson, “The Real Mrs. Roosevelt At Home And Her Personality,” Santa Fe New Mexican, October 21, 1912, 7.

43 Ad promoting Idah McGlone Gibson’s series of interviews, (Chicago) The Day Book, October 2, 1912, 9.

44 “Special World’s Series Feature,” Pittsburgh Press, October 2, 1912, 18.

45 Idah McGlone Gibson, “Why Pitcher Joe Wood Pays No Attention To ‘Mash’ Epistles,” Pittsburgh Press, October 7, 1912, 14.

46 Idah McGlone Gibson, “The Mighty Muggsy McGraw As A Woman Sees Him,” (Chicago) The Day Book, October 3, 1912, 21.

47 Idah McGlone Gibson, “Tesreau Gets More Stage Door Adulation Than a Chorus Girl,” Pittsburgh Press, October 9, 1912: 14.

48 Idah McGlone Gibson, “Woman Reporter Pries Into Secrets Of Dodgers,” (Madison) Wisconsin State Journal, October 4, 1916, 11.

49 Idah McGlone Gibson, “Ball Player Never Amounts to Much Until Married, Buck Wheat Tells Woman Reporter,” (Salt Lake City) Salt Lake Telegram, October 8, 1916, 11.

50Idah McGlone Gibson, “Author of ‘Confessions of a Wife’ Interviews John M’Graw,” Pittsburgh Press, September 29, 1917, 10.

51“Season End Worst Time for Title Team M’Graw Tells Woman Writer,” (Madison) Wisconsin State Journal, October 2, 1917, 11.

52 “Mrs. Hoover In Talk Over Radio,” South Bend (IN) Tribune, April 20, 1929, 2.

53 Katharine Brush, “Baseball is Man’s Game, But Fans’ Eyes Are On Washington Senators’ Wives As They Are Tendered Keys Of City Of Pittsburgh,” East Liverpool (OH) Review-Tribune, October 7, 1925, 1.

54 Katharine Brush, “Baby Alice Russell Is Youngest Rooter, While Eddie Moore Is Handsomest Player In Series,” East Liverpool (OH) Review-Tribune, October 8, 1925, 1.

55 For example, John E. Wray discussing a nameless female reporter in “Wallie Schang Made Worst And Most Costly Mistake of the Series, Wray Writes.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 10, 1922, 15.