Professional Woman Umpires

This article was written by Leslie Heaphy

This article was published in SABR 50 at 50

This article was originally published in “The SABR Book on Umpires and Umpiring” (SABR, 2017), edited by Larry R. Gerlach and Bill Nowlin.

Bernice Gera, center, makes a call at the Jim Finley umpire school in 1967. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

“Are you blind?” is a familiar cry for fans sitting in the stands at any baseball diamond. Fans believe it is part of their job to harass the men in blue. But what happens when that man is a woman in blue? Do the insults change? Yes. Are fans so surprised some of them do not even know how to react? Yes. But baseball has been played professionally in the United States since the 1860s. Why are people still surprised by female umpires? Because they are absolutely still a novelty. Women have had limited success breaking in to the ranks of the arbiters of the game, though the few who have been allowed to participate have proved they know the rules and how to call a game. And why have both the NBA and professional football added female referees but not baseball?

Baseball made one concession to change in 2006 when the rules committee voted to acknowledge the presence of a female umpire. “An amendment to Rule 2.00 in the Definition of Terms reads: “Any reference in these Official Baseball Rules to ‘he,’ ‘him,’ or ‘his’ shall be deemed to be a reference to ‘she,’ ‘her,’ or ‘hers,’ as the case may be, when the person is female.”

Veteran big-league umpire Larry Young, a member of the Playing Rules Committee, voted in favor of the wording.”1 Those who voted believed it needed to be done.

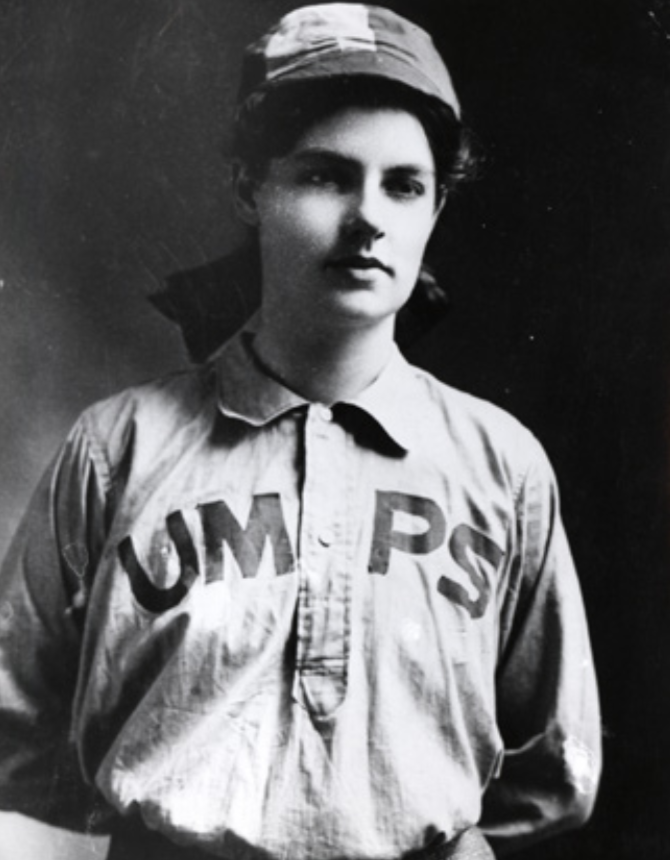

Where does the story begin for the seven US professional female umpires? One of the earliest women to be paid to umpire semipro games was Amanda Clement in the early 1900s. Her brother Hank helped get her started and people, while surprised, were impressed with her ability and knowledge. After Clement there was a long hiatus until Bernice Gera got her chance as the first professional. Gera was followed by Pam Postema and then there were Christine Wren and Theresa Cox. Ria Cortesio and Shanna Kook worked at the same time in 2003 and 2004. In addition to these ladies there is also Cuba’s Yanet Moreno, who has been umpiring in the National Series since 2003. In 2015 Guam added a female umpire to its ranks with Jhen Senence Bennett. She umpired her first game with her father. And as recently as early 2016 Jen Pawol became the seventh after receiving a contract from the Gulf Coast League upon successful completion of umpire school.

Where does the story begin for the seven US professional female umpires? One of the earliest women to be paid to umpire semipro games was Amanda Clement in the early 1900s. Her brother Hank helped get her started and people, while surprised, were impressed with her ability and knowledge. After Clement there was a long hiatus until Bernice Gera got her chance as the first professional. Gera was followed by Pam Postema and then there were Christine Wren and Theresa Cox. Ria Cortesio and Shanna Kook worked at the same time in 2003 and 2004. In addition to these ladies there is also Cuba’s Yanet Moreno, who has been umpiring in the National Series since 2003. In 2015 Guam added a female umpire to its ranks with Jhen Senence Bennett. She umpired her first game with her father. And as recently as early 2016 Jen Pawol became the seventh after receiving a contract from the Gulf Coast League upon successful completion of umpire school.

Bernice Mary Shiner Gera was born on June 15, 1931, in Ernest, Pennsylvania but grew up in Erath, Louisiana. Gera graduated from high school in 1949, with a graduating class of three. She married Louis Thomas Jr. and after their divorce married freelance photographer Stephen Gera. She worked as a secretary before turning her hand to umpiring. A longtime baseball fan, Gera graduated in 1967 from the Jim Finley umpire school but no one came calling to give her a job professionally. Gera’s experience came with local ballgames and semipro tournaments. Due to Organized Baseball’s lack of acceptance Gera began a six-year battle to get a chance to umpire. She stated, “I was not out there fighting anybody’s cause. I didn’t do what I did because of women’s liberation or anything like that. … I just wanted to be affiliated with baseball.”2 She received a contract in 1969 but it was invalidated by NAPBL President Philip Piton before she even got an opportunity. She finally won her lawsuit in 1972 when the New York Court of Appeals ruled in her favor. Gera signed her first and only contract on April 12, 1972. Her only officiated game took place on June 24, 1972, a Class-A game in Geneva, New York. She was supposed to ump a doubleheader between Auburn and the Geneva Senators but she left after the first game and never looked back. She retired after that one game. It was a tough game with at least three disputed calls, one of which led to her ejecting Auburn manager Nolan Campbell. Campbell said, “She should be in the kitchen, peeling potatoes.”3 After leaving the field Gera went to work for the New York Mets in community relations and promotions. When Gera died on September 23, 1992, from kidney cancer, her tombstone read, “Pro Baseball’s First Lady Umpire.”4 A historical marker was also placed at Blue Spruce Park near the ball field close to her home in Pennsylvania.5 Her uniform and equipment are on display at the Bridgeton Hall of Fame All Sports Museum.

After Gera left the game, Christine Wren had a short career in the 1970s. Wren played softball growing up in Spokane, Washington. She spent about 13 years playing fast-pitch softball, usually as the catcher. After being called out on a play at second that was clearly wrong, she decided she could be an umpire too. She attended umpire school in Mission Hills, California. When she finally got her chance to umpire, she commented, “I’m not a freak. I’m just somebody trying to do a job.”6 Wren umpired for two years in the Northwest League, in 1975 and 1976, and then in the Class-A Midwest League in 1977. In 1977 she made $250 a month plus $60 for travel expenses. Her most unusual experience came in an exhibition game when a Portland player came up to her and kissed her on the field. She gave him a warning and no one ever tried that again. Midwest League President Bill Walters was so impressed with Wren that he stated, “The girl is good and I want to convince Mr. (Bowie) Kuhn that she’s good.”7 She managed the players on the field like any good umpire and ejected players only when needed. Her first ejection came in a Seattle Rainiers game against Boise. She ejected catcher Ron Gibson in the seventh inning over a pitch call.8 Wren said she loved the work but hated the travel and the low pay. “The athlete in me, the ballplayer in me, always liked umpiring. It was something I always wanted to do.”9 After a few years Wren decided to call it quits and make her winter job a full-time one driving a delivery truck.10

After Gera and Wren left the game, Pam Postema was the next to try to break the barrier. Postema had the most success before Ria Cortesia made it to Triple A in the early 2000s.

Postema umpired for 13 years before filing a lawsuit against major-league baseball after her career stalled at the Triple-A level, following three years in the Pacific Coast League. Postema grew up in Willard, Ohio (born April 1954), playing softball and baseball with her brothers. She even played some football with her brothers growing up. Though she played the game she never thought about umpiring until she got older. She was waitressing at a Red Lobster when she read an ad about umpire school.

She started in the Gulf Coast League in 1977 after attending the Somers School in Daytona Beach, Florida, as one of 130 students. She wanted to be sure she made the cut because she was a good umpire and not because she was a woman. “And if I wasn’t good enough I didn’t want to make it then just because I was a woman.”11 Postema actually applied three times without ever getting even a reply. She decided to just show up and ask for a chance in person, which she got. After graduating 17th in her class, Postema got her first assignment in the Gulf Coast League. After her time in the Gulf Coast League Postema moved to the Class-A Florida State League and then the Double-A Texas League in 1991. By 1993 Postema found herself promoted to the Pacific Coast League, where she worked for four years before making her final move to the Triple-A American Association. Postema commented on her career saying, “I love every moment of my work.”12 No matter how much she loved her work, Postema still had to fight for everything she got. One of the more difficult things she had to deal with in many parks was the conditions in the locker rooms because they did not have accommodations for female umpires. At many parks the best that could be done was to hang a sheet to give her some privacy while she changed to go out onto the field.

Postema got the chance to umpire a spring-training game between the Cleveland Indians and San Francisco Giants in 1982. For her the game was like any other for an umpire trying to earn a chance to move up to the next level. Postema was assigned to “B”-level spring-training games to get more experience after umpiring the previous fall in the Arizona Fall League. She was working to earn her dues like any other umpire. She said she took no more abuse than any other umpire. She stated, “I get the same amount of harassment as any ump, I think, and there’s been no favoritism, no prejudice. I’ve been really lucky and worked with super umps. It’s no big deal being a woman ump.”13 Postema also commented that any umpire who was the least bit different would take flak, if they were fat, or black, or a woman. Her answer was the same as any other umpire: If you get too much flak you throw them out.14

As expected, reaction to Postema’s work was mixed. Manager Jim Fregosi said, “I hardly noticed her so I guess she did okay.” Pitcher Tim Burke commented on her calling balls and strikes, saying, “She’s just another mask behind the plate.” When she tossed batboy Sam Morris for not retrieving a chair thrown onto the field by his manager, the reaction was loud and wide. Postema believed she did the right thing and maintained that if she had been a man no one would have said anything at all.15 Red Sox superstar Wade Boggs said, “I have no objection if she can do a good job. If she’s there as a publicity stunt; I don’t agree with that.”16 The real compliment for Postema’s skills came from Louisville outfielder Jack Ayer who said, “Tell you the truth, I don’t really recognize that she’s a woman. I don’t have time for that.”17 Randy Kutcher, a utility infielder for the Boston Red Sox, commented, “She does a good job. She’s as good as anybody.” Kutcher had a unique perspective, having had the chance to see Postema umpire for five years at Double A and Triple A.18 Catcher Ozzie Virgil thought she did a good job. “I had no complaints. I was really impressed with the way she handled all the stuff people in the stands were yelling at her.”19

In contrast, Bob Knepper asserted that God did not like what she was doing in a man’s job.20 Toby Harrah, manager of the Oklahoma City 89ers, got thrown out by Postema and was not complimentary in his reactions. Harrah stated, “she just doesn’t grasp the game of baseball. If you haven’t played the game — and I’m sure she hasn’t — you miss the grasp.”21 Postema’s reaction was simply that she was trying to make the major leagues like any other umpire. Dick Butler, who scouted umpires for the American League, said she was there and so why not give her a chance.22 Postema’s best chance at making the majors was lost when Commissioner Bart Giamatti died. He had seemed receptive to the idea of a woman moving up to the highest level of baseball.

Postema also had to deal with those who only saw her as a woman and never as someone who could control a game. A reporter in Cuba simply referred to her as “un mujer muy bonita, por cierto (a very pretty woman, by the way).”23

Postema’s real trouble developed because she never got a chance to move beyond Triple A. By Organized Baseball rules there was a limit to the years one could spend in the minors without being called up to the majors. If one did not get the call then they were let go, as Postema was. She believed that she was let go because of her gender and not because she was unqualified. The interesting issue for Postema was that previously she had been ranked at the top of the list for umpires moving up and then without any indications or written concerns she dropped from the top to out of contention for an opening,

Postema filed suit in Manhattan District Court in 1991 because the league did not promote her to the majors even though she had excellent performance reviews. She sued for damages, money, and a job. US District Judge Robert Patterson ruled that her case could go forward to trial.24 Postema was able to bring suit against the National League but not the American because of the number of job openings each had and potential candidates for those jobs. After leaving baseball she went to work for Federal Express in San Clemente, California.25

After her career ended, Postema received a number of honors. In 2000 she was inducted into the Shrine of the Eternals. She also published a book about her experiences in 1992 entitled You’ve Got to Have Balls to Make It in This League. In the book she describes her view of why women have such a difficult time even getting a chance to umpire. “Almost all of the people in the baseball community don’t want anyone interrupting their little male-dominated way of life. They want big, fat male umpires. They want those macho, tobacco-chewing, sleazy sort of borderline alcoholics.”26

After attending the Wendelstedt umpire school in 1982, Perry Lee Barber began her still continuing (as of 2015) career; for her long and varied career, which included being assignor of umpires for the independent Atlantic League from 1998 to 2001, see her essay “The Stained Grass Window” in this book.

After attending the Wendelstedt umpire school in 1982, Perry Lee Barber began her still continuing (as of 2015) career; for her long and varied career, which included being assignor of umpires for the independent Atlantic League from 1998 to 2001, see her essay “The Stained Grass Window” in this book.

Theresa Cox of Ohio (later Cox-Fairlady) had a short career after Postema and together they paved the way for Ria Cortesio and Shanna Kook. Cox went to the Harry Wendelstedt School for umpires and graduated fifth out of a class of 180. Cox never really got a fair chance as she was told her voice was too high and she could not really wear the uniform. When she tried to change the tone she was told her voice now sounded fake. Since Cox umpired college and high-school games, her voice was simply an excuse for not wanting her on the diamond. Wendelstedt challenged that view when he claimed Cox was “…the best female candidate I’ve ever had.”27 He trained 28 women and 5,000 men so his view was certainly one to be taken seriously. In 1989 Cox worked two Double-A Southern League games before umpiring for two years, 1989-1990, in the Arizona Rookie League. She said that in her Arizona League season she walked 22 batters in her first game before the pitchers discovered her strike zone. Cox acknowledged that Postema’s work helped her in trying to break into the game. “What she went through has made it easier for me, and if it’s not me who is the first woman ump, then maybe I’ll make it easier for somebody who follows after me. But we have to keep trying. It’s like life, either you evolve or you die out.”28 In 2008 Cox-Fairlady had a chance to umpire a Mets spring-training exhibition game against the University of Michigan. The game was not that unusual but the umpiring crew was, since it included four women, one of whom was Cox-Fairlady. She was joined by Perry Barber, Ila Valcarcel, and Mona Osborne. When she was not umpiring Cox drove for UPS in Birmingham, Alabama, to supplement the money she made umpiring.29

Next in line was Ria Cortesio (real name Maria Papageorgiou), from Rock Island, Illinois, who got her start as a professional umpire in 1999. She decided to become an umpire when she was about 16, after talking with umpire Scott Higgins, who sat down with her and explained how the whole process worked.30 Growing up she never got the chance to play since girls were expected to play softball and baseball was a boy’s game. She played in her front yard with her cousins but never in organized ball. She graduated from the Jim Evans Umpire Academy in Kissimmee, Florida, after attending the five-week program in 1998 as her second try, having also attended in 1996. Cortesio was one of only two women each time she attended the school. In addition to umpire school, Cortesio was also a graduate of Rice University, graduating summa cum laude. Evans commented after her graduation from umpire school, “I don’t think sex should be a criterion for umpiring in the big leagues.”31 Her goal was to work her way up through the ranks and win one of the 68 major-league umpiring jobs. She even cut her ponytail and lowered her voice so she would not stand out as much. But Cortesio was up against a large group of men working for the same goal. By 2006 she was umpiring the Futures game and home-run derby in Pittsburgh. In 2007 she got the opportunity to umpire a spring-training game between the Cubs and the Diamondbacks. Derek Lee, first baseman for the Cubs, stated, “It’s awesome. I think it’s about time. Female eyes are as good as male eyes. Why can’t they be umpires?”32

During a 2007 Double-A game Cortesio received the ultimate compliment from a fan who said, “He might be young, but he looks like he’s consistent. So far, he’s called a good game.”33 The fan had no idea the umpire was female and therefore he judged the performance solely on the quality and not the gender. One of her fellow umpires, Jason Stein, got a chance to work with her in the Futures game and continued to be impressed. “She’s good enough to be here,” said Stein, who worked in the Double-A Texas League. “She’s just as good as we are. If she gets the opportunity to advance to the big leagues and be successful, it would be a great thing. I’m pulling hard for her.”34 “She has inconsistencies but she’s just as good as any other umpire,” said Suns pitcher Joel Hanrahan, who also saw Cortesio in the Pioneer League in 2000 and in the Florida State League in 2002.35

Not all reactions were positive to Cortesio’s work. While she seemed to get less criticism than Postema and the other early pioneers, there were still critics of her as a female umpire. One of those was George Steinbrenner who expressed displeasure over her strike zone when she called a rehab game for Roger Clemens. Told that Cortesio had once umpired Clemens’s boys in Little League in Texas, the New York Yankees owner huffed: “Is that right? Well, that’s good; I guess she’ll go back there.”36

Cortesio never really saw herself as a pioneer, just someone who wanted to umpire in the major leagues. “Until I work a regular-season major-league baseball game, I haven’t done anything,” Cortesio said. “I don’t want to be a pioneer. I just want to do my job.”37 Another time, she said, “It never crossed my mind that because I was a female, I couldn’t do this job. I was lucky to be raised by parents without barriers; that there is no difference between a male and female doing the same job. The guidelines should be equal for both as long as you can do the job.”38 At the same time Cortesio realized she could do a lot to get other women involved.

Cortesio got the call from Mike Fitzpatrick (executive director of the Professional Baseball Umpires Corporation, the umbrella organization for minor-league umpiring) telling her they were letting her go after the 2007 season. There were no openings at the Triple-A level and her ranking had fallen, making her ineligible for a promotion after nine years. Because there are few openings, senior umpires can be let go if they do not move up, to make room for new hires.39

Other major-league players and managers agreed with Derek Lee and thought Cortesio had earned her chance. Willie Randolph commented, “I hope she gets her shot, that’s important.” Felipe Alou believed a female umpire like Cortesio would be good for the game, claiming, “I believe a woman umpire would bring some good ingredients to the game and added interest.”40

When asked in 2007 why baseball and not softball, Cortesio had the following to say:

I bet you if you go to any high school or college softball team and ask any of the girls, probably most of them when they’re growing up dreamed of playing major league baseball. You know, baseball is our national pastime, but for some reason half of the nation is shut out of it. There’s this pretty ridiculous stereotype, I think, in this country that baseball is just for boys, and girls, go play with dolls or play softball or something.41

Cortesio, the last woman to rise through the minor-league ranks to the present day in 2016, helped mentor Canadian Shanna Kook; they were the only two ladies whose career overlapped.

In 2003 Torontoan Kook umpired in the Pioneer League (she spent two years there) after graduating from the Harry Wendelstedt Umpire School. Her first game she umpired behind home plate in a game between Provo and Casper. Provo manager Tom Kotchman said, “I’ll give her credit. She was not tentative. It’s tough to tell from the side but our catcher said she called a very good game.”42 Before taking up her place on the diamond, Kook attended Clinton Street Public School, where she excelled in the classroom and on the diamond. Kook joined the school baseball team and helped lead it to a championship during her senior year. Kook then enrolled at McGill University, where she majored in music and played the viola. She missed baseball and wanted to return to the game as an umpire.43

Kook’s view on umpiring was best stated when she said, “I really don’t care if people notice me. Really the more I’m anonymous, the better. If people don’t know who I am, that’s fine, because then I am doing my job.”44 She learned her craft on the diamonds in Canada starting at the age of 16 and by 2002 she was the crew chief for the Women’s World Series. She attended a clinic to get started at the community center level. After starting college and realizing she needed more money, she returned to umpiring and eventually rose to umpiring higher-level games. From there she was invited to attend a women’s umpire clinic in Canada and then she went for one week to the Jim Evans Academy of Professional Umpiring. Kook was hooked on umpiring and left school to pursue her chance. She joined the small rank of professional female umpires.45

After Cortesio was let go, Kate Sargeant tried to earn a spot, attending the Wendelstedt School in Florida in 2007 after umpiring with her dad in the Peninsula Umpires Association. She made it to the final selection process but was not picked for a position. She was the last umpire on the eligible list and she did not get a call. She also had previously attended the Jim Evans School twice. Her only shot came in the independent New York State League, where she spent two years umpiring (2007-2008).46 Those who worked with her had no qualms about being on the field with Sargeant, saying she knew all the rules. After her failed attempt, league officials were asked when they thought a woman might get an opportunity. When MLB Vice President Mike Teevan was asked if it might be at least another six years before a woman could break into the majors, he said, “Basing on the roads that most [umpires] traveled, that’s fair to say.” He added, however, that the league “would love to see” a woman officiate one day.47 Sargeant continued to umpire high-school games for a bit longer but finally gave up her dream and became a forest ranger with Canada’s National Forest Service.48

One of the most successful female umpires in recent years has been working under the radar in Cuba, Yanet Moreno. Moreno loved baseball as a child but just like other women had trouble playing because others, like her father, thought baseball was for boys and not girls.49

One of the most successful female umpires in recent years has been working under the radar in Cuba, Yanet Moreno. Moreno loved baseball as a child but just like other women had trouble playing because others, like her father, thought baseball was for boys and not girls.49

In 2016 one more female umpire was added to the ranks of professional baseball. Jen Pawol graduated from Minor League Baseball’s umpire camp along with Annie Monochello. While both graduated, only Pawol got an official assignment with the Gulf Coast League, making her the first female umpire at the professional level since 2007. Pawol brought a lot of umpiring experience from both baseball and softball. She played soccer and softball at West Milford High School (New Jersey) before getting a scholarship to play at Hofstra from 1995-1998. Pawol earned All-American honors as a catcher, hitting .332 with 102 RBIs. She umpired for fast-pitch softball as well as being an NCAA Division I postseason umpire. She also umpired in the Big Ten Conference from 2013 to 2015. In her first Gulf Coast League game Pawol umpired behind home plate. She worked a flawless game with the Blue Jays manager Cesar Martin saying, “She did a great job. Controlling the game, all these things. It was a nice game.”50

Pawol is also an artist. She earned her BFA from the Pratt Institute and then an MFA from Hunter College. When she was not umpiring in previous years she also worked part-time as an eighth grade art teacher. Pawol sees a lot of correlations between painting and baseball, the sounds the rhythm of the game, the artistry of the players, etc. Pawol stated, “I don’t really view umpiring as a gender job, I just view it as, if you’re good at it, and you like it, you should do it.”51

The path to becoming an umpire is a long and arduous journey for anyone but especially for a woman. After the establishment of an umpire school for the minor leagues in 2011, only one woman attended and graduated, Sarah Allerding, who then decided to become a deaconess in the Lutheran Church. She said she always felt welcome and simply made the choice to join the church. If she had made the cut and decided to pursue umpiring, it still would have been a minimum of six years before there could have been a female umpire, based on how promotions work. So there have been only six women in the professional ranks and we are still years away from possibly seeing that glass ceiling broken in the United States, even though the NBA and NFL have both employed female referees. Some make the claim that because women do not play baseball as much that is why there are fewer female umpires, but you do not have to play to know the rules.52

Writer Derek Crawford ended his article on the trials of female umpires saying, “Baseball truly is a fraternity and a brotherhood, but we live in a society in which a woman can run for President, sit on the Supreme Court, fight on the front lines in combat, but can’t put on a chest protector and call balls and strikes in a Major League ballpark for a living.”53

LESLIE HEAPHY is an associate professor of history at Kent State University and has been a SABR member since 1988. She is the chair of the Women in Baseball Committee and serves on the committee for SABR’s annual Jerry Malloy Negro League Conference. She is the author/editor of six books on baseball history and editor of “Blackball,” a national peer-reviewed journal on black baseball.

Notes

1 Ben Walker, “Just One of the Umpires,” Seattle Times, July 9, 2006.

2 Craig Davis, “She Never Wanted to Be a Pioneer,” Chicago Tribune, October 8, 1989.

3 Lisa Winston, milb.com, June 22, 2007.

4 vrml.k12.la.us/ehs/history/berniceshiner.htm.

5 Edward J. Shiner obituary, New York Times, August 14, 2014.

6 “Woman Umpire Has a Single Goal,” The Oregonian (Portland), July 1, 1976: C8.

7 Ibid.

8 “Christine Wren Uses Her Thumb,” Seattle Times, June 27, 1975: C3.

9 Howie Stalwick, “Spokane Native Paved the Way for Postema,” Spokesman Review (Spokane, Washington), March 8, 1988.

10 “Kill the Ump. If It’s Christine Wren, Kiss Her,” People Magazine, July 14, 1975.

11 Linda Lehrer, “Sporting Chance,” Chicago Tribune, June 21, 1992.

12 Mal Bernstein, “Who Is That Woman Behind the Mask,” Christian Science Monitor, July 29, 1985.

13 AP, “Female Umpire Inches Toward Major Leagues,” Dallas Morning News, March 14, 1982: 47. 1982.

14 Robin Finn, “Female Umpire Aims for Majors,” Lakeland (Florida) Ledger, July 28, 1987:16.

15 “Batboy Ejected for Disobedience,” Mobile Register, May 27, 1984.

16 Stephen Harris, “Woman Behind the Plate No Threat,” Boston Herald, March 15, 1988: 97.

17 “Umpire Pam Postema Is Fighting Tradition,” Mobile Register, July 6, 1987: 4D.

18 Stephen Harris.

19 Jayson Stark, “She Awaits a Call From the Majors,” philly.com, March 13, 1988.

20 Bernie Lincicome, “Woman Umpire Balks at Spotlight,” Chicago Tribune, March 20, 1988.

21 Mobile Register, July 6, 1987: 4D.

22 Jerome Holtzman, “Lady Ump Could Find Home in Majors,” Chicago Tribune, April 6, 1986.

23 Luis Perez Lopez, “No Maten al Umpire. Que es Una Mujer!” El Miami Herald, June 2, 1980: 9.

24 Mobile Press Register, July 14, 1992: 3C.

25 “Former Major League Umpire Pam Postema Sues Baseball,” December 1991.

26 Pam Postema, You’ve Got to Have Balls to Make It in This League (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992).

27 Anna Quindlen, “I Don’t Know Why a Young Lady Would Want this Job,” Chicago Tribune, September 3, 1991.

28 Robin Finn, “Ohioan on Deck,” New York Times, December 25, 1989.

29 Perry Barber and Jean Ardell, “Women in Black,” Cooperstown Symposium, 2011-2012, State University of New York, College of Oneonta, 2013, 55; Cox Hopes Her Fate as Umpire Turns Out Better Than Postema,” Spokesman Review, December 25, 1989.

30 Michel Martin, “Baseball’s Leading Lady,” NPR, April 30, 1977.

31 Josh Robbins, “Female Umpire Hopes for Shot at Major Leagues,” Lawrence (Kansas) Journal-World, May 12, 2007: 16.

32 Lisa Winston.

33 Josh Robbins.

34 Lyle Spencer, “Female Ump Gets Futures Game Nod,” MLB.com, July 9, 2006.

35 Jeff Elliott, “Female Umpire Plays Out Dream,” Florida Times-Union (Jacksonville), June 25, 2003.

36 Ben Walker, “Just One of the Umpires,” Seattle Times, July 9, 2006.

37 Lyle Spencer.

38 Jeff Elliott.

39 Associated Press, “Baseball’s Only Female Umpire Fired,” Houston Chronicle, November 1, 2007.

40 AP story, “RI’s Cortesio Is Hoping Not to Get Rung Up,” Quad-City Times, September 8, 2005.

41 Michel Martin.

42 Jason Franchuk, “Umpire Story,” Daily Herald (Provo, Utah), July 10, 2003.

43 Justin Skinner, “Clinton Street PS Looks for Past Grads to Celebrate 125 Years,” InsideToronto.com, October 26, 2012.

44 Fran Chuck, “Umpire Story,” Toronto Daily Herald, July 10, 2003.

45 Leslie Heaphy, ed. Women in Baseball Encyclopedia (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Publishing Inc., 2006), 57-58.

46 Pat Borzi, “Woman Umpires Are Striking Out in MLB,” ESPNW.com, August 9, 2011.

47 Lucy McCalmont, “MLB Probably Won’t Have a Female Umpire for at Least Six Years,” Huffington Post, April 16, 2015.

48 Terry Mosher, “Female NK Grad Sargeant Made Run at Umpiring in Pros,” Kitsap Sun (Bremerton, Washington), April 12, 2014.

49 Shasta Darlington, “In Cuba’s Male Baseball League, Female Umpire Calls ’Em Like She Sees ’Em,” CNN.com, January 6, 2010.

50 Paul Hagan, “Female Umpire Calls Game in Rookie Ball,” MLB.com, June 24, 2016.

51 David Dorsey, “Jen Pawol Travels Rare Baseball Path as an Umpire,” News-Press.com, July 10, 2016; David Wilson, “Jen Pawol Ends Female Umpire Drought on Opening Day of GCL,” Bradenton-Herald, June 24, 2016.

52 Lucy McCalmont. Of course, even fewer women play football.

53 Derek Crawford, “Behind the Mask: Where Are the Women?’ baseballessential.com, April 4, 2015.