Ty Cobb, Actor

This article was written by Rob Edelman

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the Peach State (Atlanta, 2010)

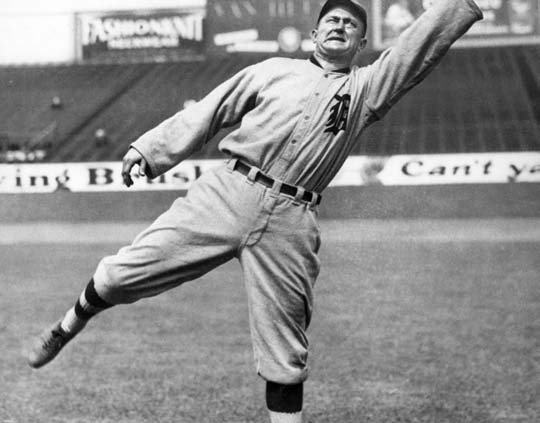

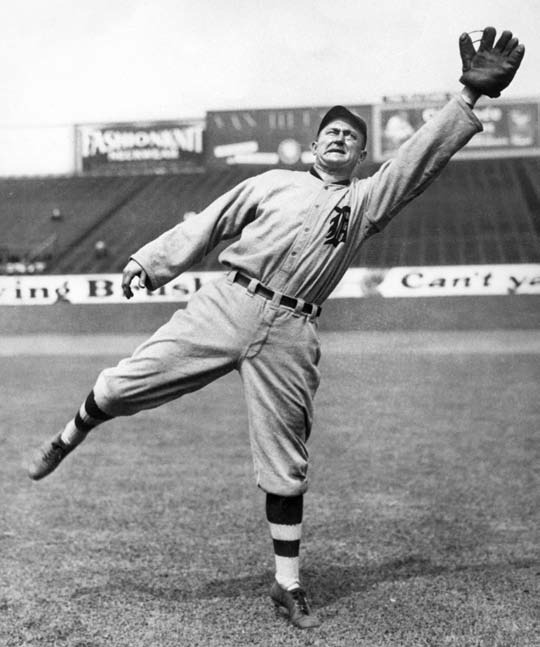

During the first years of the twentieth century many of the most celebrated—and marketable— major leaguers supplemented their incomes by headlining in vaudeville or touring in legitimate plays during the off-season. A few even appeared in motion pictures: a new medium that was revolutionizing the way in which Americans passed their leisure hours. And so, given his status as one of the biggest names in baseball, Ty Cobb was able to earn hefty paychecks first by taking cues from a stage director rather than a field manager and then by trading in his glove and bat for a film script.

As his star rose in the major leagues, theatrical producers began approaching Cobb and proposing that he enter vaudeville or tour in a play. As early as 1907, the media reported that the Detroit Tigers’ flychaser was regularly turning down such bids. Cobb himself explained that he had “often received offers to go before the footlights, but realizing that I am a ball player and not an actor, I declined all these propositions.” In contrast to his celebrated on-field ferociousness, he feared that a poorly received performance might make him a laughingstock.

All this changed in the summer of 1911. Cobb would finish the season leading the American League with 248 hits, 47 doubles, 24 triples, 127 RBIs, 147 runs scored, a .621 slugging percentage, and a .420 batting average. But before the campaign’s end, he was approached by Vaughan Glaser, an actor-director who then was performing in and managing a Southern-based stock company. Glaser is one of countless long-forgotten theater professionals who toiled for decades on the fringes of the limelight, appearing in scores of stock productions. In 1938, he won fleeting mainstream notoriety when he originated the role of Mr. Bradley, a high school principal, in the Broadway production of What a Life — the Clifford Goldsmith comedy that introduced to the world a brash, awkward teenager by the name of Henry Aldrich. The following year, Glaser was cast as Bradley in the screen version of What a Life and reprised the part in Paramount’s subsequent Henry Aldrich film series. He also was seen in two Alfred Hitchcock features, Saboteur (1942) and Shadow of a Doubt (1942), and had small roles in three baseball-related films: Frank Capra’s Meet John Doe (1941), whose title character, played by Gary Cooper, is a lanky ex-bush league hurler; the Lou Gehrig biography The Pride of the Yankees (1942), also featuring Cooper; and Capra’s Arsenic and Old Lace (1944), which opens with an Ebbets Field sequence that is a must-see for Brooklyn Dodgers aficionados.

FROM BALL FIELD TO FOOTLIGHTS

Glaser had known Cobb for several years, during which he had been constantly bugging the ballplayer to appear in one of his productions. Now, at last, Cobb relented. According to the Atlanta Constitution, he acquiesced because Glaser’s wife “revealed to him that he possessed natural talents as an actor.” But he more likely agreed for a more practical — and altogether different — reason. At the time, Cobb was not a wealthy man. He had not yet amassed his fortune by investing in real estate, playing the financial markets, and accumulating Coca-Cola Company stock. But now he was married and starting a family, and he certainly could use the extra cash. So he agreed to tour in a Glaser-mounted stage production that would begin at the end of the baseball season. His salary for the tour reportedly was in the $10,000 range: certainly a handsome sum for 1911-12, and far more than Cobb ever could earn accepting the kind of working person’s job that many big leaguers then undertook during the off-season.

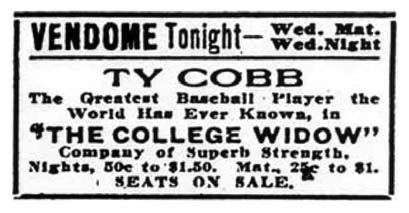

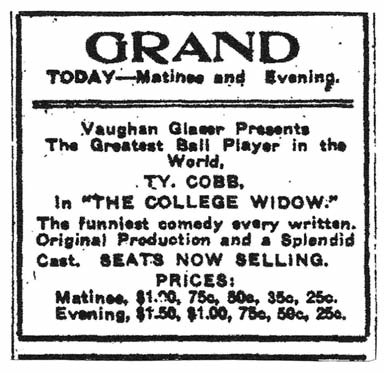

In early July, Sporting Life reported that Cobb “was seriously considering an offer to go on stage next Winter. . . . Several prominent theatrical men and outfielder Jimmy Callahan are said to be interested in the venture.” The deal became official in August. The production Glaser handpicked for the ballplayer was The College Widow, a comedy written by George Ade, which had lasted 278 performances when it debuted on Broadway in 1904. The plot centers on Billy Bolton, a star footballer who is intent on playing for Bingham College. Jane Witherspoon, the resourceful daughter of the head man at Atwater College, Bingham’s archrival, schemes to convince Billy to join her school’s team. As the story progresses, romance blossoms between heroine and hero.

Cobb had seen a production of The College Widow in Detroit three years before and believed that, given his public persona, the play was an appropriate choice. When the tour was in its planning stages, Glaser briefly considered transforming Billy Bolton into a flychaser but decided to maintain the original characterization. After a brief rehearsal period, the tour began in early November. Its first stop was the Taylor Opera House in Newark, New Jersey. Also cast in the production was another big-leaguer, albeit one who would transcend the fame of Jimmy Callahan. Glaser signed Shoeless Joe Jackson, who had just completed his first full season in the American League. Jackson was to appear in a supporting role, as a heavy, but his run was short-lived. “Just before the curtain was hoisted on the first night,” Sporting Life reported, “Joe got to thinking of old Greenville, South Carolina, where everybody knows him, and he decided to go there instead of upon the stage.”

Unlike Jackson, Cobb was determined to stick with the show. Throughout its run, audiences regularly applauded him not so much for his acting ability as his mere presence. While no John Barrymore, Cobb did not embarrass himself onstage. One of the first reviews of the production, which appeared in the Trenton True American, typified most of those that followed. “Not content with grabbing the top-most twig of laurel in the baseball world,” the paper reported, “Ty Cobb . . . broke into the theatrical world last night . . . and, though he swung at some wild ones, managed to connect for a ‘Baker’ before the game ended . . . The ‘Georgia Peach’ isn’t attempting to elevate the stage. He is out for the money, but, be it said to his credit, he is no lemon when it comes to the histrionic.” Bert Cowan, who is alternately described as Cobb’s “business manager during that brief fling at acting” and one of the performers in Glaser’s company, noted that the ballplayer-turned-actor was “exceedingly sharp and quick. That was why he was able to handle the acting chore.”

Several weeks into the tour, Cobb recalled, “Much to my surprise, I managed to get through my first night on the stage without that awful bugaboo, ‘stage fright,’ attacking my heart and dropping me in my tracks. But I had been warned so much regarding such an attack that I made every preparation to guard against it. It was just like figuring out what kind of a ball a pitcher was going to put over. I knew it was coming and waited for it.” Then he added, “A few appearances on the stage gave me reassurance and now I am perfectly at home. I find stage work wonderfully interesting and I like it.”

One example of how Cobb maintained his stage presence was cited by Vaughan Glaser. In the middle of a performance, Glaser noticed that several sweaters used in the production were missing. He began questioning a stagehand, and his query was met with hostility. Cobb, who was waiting offstage for his cue, overheard the conversation and promptly stepped between Glaser and the stagehand. After knocking down the stagehand, he coolly strode onstage and flawlessly delivered his lines.

Another incident involving Cobb’s swing-first-and-ask-questions-later behavior occurred during the show’s run at New York’s Lyceum Theater. Without his knowledge, the show’s publicist planted a phony police officer in Central Park, through which the ballplayer was motoring. In his autobiography, My Life in Baseball, Cobb recollected that he was driving at a “moderate pace” when the faux cop stopped him — and informed him that he was under arrest. When he resisted, and the policeman persisted, the Georgia Peach “made a little pugilistic history. When the smoke cleared, the man in blue was sans his helmet and coat and bleeding variously. Picking himself up, he vanished over the horizon.” Cobb was convinced that his action would land him in the clink. But then he spied a photographer lurking in a nearby bush, and he soon realized the incident was a stunt, fashioned to “grab off some Page One space.”

TOURING ON HOME TURF

Almost immediately after its premiere, The College Widow troupe headed below the Mason-Dixon Line. As Cobb and company traveled from venue to venue, he was treated like reigning royalty. In Asheville, North Carolina, the Georgia Peach was feted with a preperformance reception and post-performance banquet. The play was booked into two cities in Cobb’s home state: Augusta and Atlanta. The ballplayer then was living in Augusta and the local paper, the Augusta Chronicle, gave the tour maximum coverage. First the Chronicle extensively detailed Cobb’s reception in Newark. Then on November 11, the paper reported that his “friends in Augusta are preparing to give him a rousing reception upon his first appearance here as an actor. He will be at the Grand [Opera House] . . . next Saturday, matinee and night, and will be banqueted several times while in the city. He has friends in Augusta by the hundreds and there will be a fight to see which body of his friends will be able to do the most for him.” In the flurry of items that appeared in the paper during the following week, the tour was dubbed one of the “biggest local events in theatrical history.” The play was described as “Vaughan Glaser’s mammoth revival and artistic production,” “one of the most pleasant plays of the American stage,” and “a story of college life which will remain as long as the American drama exists.”

Of his acting, the Chronicle gushed that, “without doubt, [Cobb] has been the dramatic find and surprise of the current season.” The paper further reported:

Since his advent on the stage Cobb has been making a reputation for himself which is second only to [what] he has achieved on the diamond . . . the simple fact that Cobb really acts and acts in a manner which ranks him high in his new calling is very refreshing. . . . His various speeches were delivered in a manner which would have made actors much longer in the business than he, proud of themselves. . . . his natural ease and grace stood him in good stead at all times . . . it might well be said that he is a better ball player than any actor and a better actor than any ball player.

The Chronicle also noted that, at each performance, “Ty Cobb’s friends turned out in large and enthusiastic numbers, and showed their cordial appreciation of him . . . by heartiest applause upon his every appearance and repeated curtain calls at the end of each act.” One of those in attendance was an American of note who had spent a goodly portion of his childhood in Augusta: Woodrow Wilson, current New Jersey governor and future United States president, who “joined a box party at the Grand” for one of the shows.

On his arrival in Atlanta, Cobb was welcomed by members of the city’s Ad Men’s Club. A photo of the ballplayer being greeted by the club was printed in the Atlanta Constitution. He also was “the recipient of a great reception” at the Transportation Club, which was attended by 75 community leaders. The show was booked into the Atlanta Theater and, after one performance, the Atlanta Journal gushed that “Tyrus Raymond was compelled to respond to vociferous curtain calls, and his speech, which set everybody laughing, proved his honest appreciation of the welcome accorded him.” The paper added, “Entering the theatrical game without the least training for it Cobb has worked with a true Georgia Spirit.” In a rewording of the Augusta Chronicle reportage, the Atlanta Constitution noted that Cobb “has proven the dramatic find of the year, and it can be truthfully said that he is a better ball/player [sic] than any actor, a better actor than any ball/player [sic] and as good an actor as many who make it their life business.”

The College Widow then moved on to Nashville’s Vendome Theater. The Nashville Banner reported that Cobb, “the greatest baseball player the world has ever seen . . . is the guest of Nashville [and] was given the royal reception by the people of the city.” During his stay in town, he was afforded the company of various prominent Tennesseans, starting with the state’s governor, Ben W. Hooper. Cobb also attended a couple of Vanderbilt University football scrimmages and, on his second visit, he donned a team uniform, practiced with the players — at one point, he reportedly punted a football for 50 yards “in the face of a brisk breeze” — and sat down for an interview that appeared in the school newspaper. Of his performance, the unidentified Banner writer opined, “On the stage Mr. Cobb is maintaining the same high average that has marked his work on the diamond.”

Cobb met with similar receptions in other Southern cities — with one glaring exception. The story goes that Allen G. Johnson, sports editor and drama critic of the Birmingham News, instigated the hiring of Cobb as the paper’s sports editor while The College Widow was playing in the Alabama city. A black streamer across the paper’s sports page announced Cobb as the new editor. But the ballplayer’s job consisted of his dictating a statement in which he promised that his Tigers would cop the pennant during the upcoming campaign.

Even though that day’s paper was a hot-seller, the News’s managing editor was not amused. He promptly ordered Johnson to not just review The College Widow but to offer an honest judgment of Cobb’s thespian abilities. While the ballplayer’s performance earned him a curtain call at the second-act finale, Johnson harshly criticized his acting prowess. Upon learning of the review, Cobb wrote Johnson a cutting missive in which he retorted, “Your criticism is beneath my notice, but I just want you to see what a few real critics say about my work.” Cobb included clippings of previously published critiques and added, “I am a better actor than you are, a better sports editor than you are, a better dramatic critic than you are. I make more money than you do, and I know I am a better ball player — so why should inferiors criticize superiors?”

With tongue steadfastly planted in cheek, Johnson answered Cobb with a letter of his own in which he declared, “I admit that you are a better critic, actor, sports editor, and money maker than I am, Mr. Cobb, but I refuse to admit that you are a better ball player. I have seen you play ball and know what you can do, but you have never seen me in action on a diamond. Therefore I now challenge you to a game at Rickwood Field, the Birmingham Southern League ball ground, July 4, for the championship of the world. If you do not appear to play me I will claim the championship by forfeit.” Unsurprisingly, Cobb never responded to the challenge.

HEADING NORTH

After playing the various Southern cities, The College Widow troupe toured the Midwest. On December 5, the Pittsburgh Leader reported that Cobb’s “coolness, familiarity with the lines, clearness of enunciation and absence of stage fright elicited much applause” during a performance at the Lyceum Theater. However, during one of the Pittsburgh performances, the ballplayer-turned-actor forgot his lines. His wife Charlie and his two children had come to town from Detroit and were seated in an upper box. Upon his initial onstage appearance, Cobb became distracted when Ty Jr., his two-and-a-half-year-old son, blurted out, “Daddy! Daddy!” “I was so confused,” Cobb reported, “I couldn’t say anything, but in the applause that followed I managed to recover.” Several days after the incident, Cobb told the Toledo Times, “I am striving to do my best [onstage] and will continue to do so, just the same as I try to play baseball.”

After a brief stay in Toledo, the troupe moved on to such venues as Toronto, Kalamazoo, and Detroit (where it followed Germany Schaefer’s vaudeville act into the Lyceum Theater). On the final day of the year, The College Widow entertained an audience in Chicago. By this time, however, Cobb was becoming fatigued by the grind of traveling, performing night after night, and meeting and greeting well-wishers and hangers-on. Additionally, he now was concerned that this routine might negatively impact on his ball playing during the upcoming season. The College Widow was supposed to tour the Eastern United States through March, ending right before the opening of spring training. But after some additional play dates, the last in Cleveland, Cobb ended the show’s run — in mid-January. Even then, the ballplayer and the tour still were earning positive press. “With Ty Cobb as star in a George Ade comedy,” reported the Cleveland Leader on January 9, “the [Cleveland] Lyceum is ‘knocking ‘em off the seats’ . . . the theater was packed last night from boxes to bleachers and ‘Ty’ kept his average well above .400 as Billy Bolton, Atwater College halfback.”

Cobb explained his reasoning for cutting the tour short by declaring, “Here I am at the end of several months on the boards four pounds under my playing weight when under . . . more natural conditions I should be from five to ten pounds over that notch.” He added, “I am becoming nervous and I miss my regular sleep. It was my ambition . . . to become a good actor, but in attaining that object I see that my usefulness as a baseball player is bound to suffer and so I have decided to cut out the stage for the pastime which first made me the reputation I enjoy.” An anonymous writer in Baseball Magazine noted that, “according to Tyrus, the month of one-night stands which he played through the south was worse than facing Walter Johnson or Russ Ford 154 games in the season.”

After quitting the show, Cobb returned to Detroit to spend time with his family and rest up for the new season. Overall, he spent ten weeks playing Billy Bolton. “I believe I was fairly successful for a beginner,” Cobb modestly declared afterwards. Decades later, he maintained that the stage actor’s life was tough and demanding. Life on the road “proved to me that actors of my day, more than ballplayers, had to be iron men.”

Upon reclaiming his spot in the Detroit outfield, Cobb viewed his time in The College Widow as a one-shot experience. In a bylined article published in the New York Times in 1919, Christy Mathewson observed, “Cobb was pretty good as an actor, too. I saw him do it. But I don’t think Ty cared much for the job, from what he told me, and because he never went back after more, in spite of big offers.”

FROM STAGE TO SCREEN

Big Six only was partly correct. While Cobb never revisited stage acting, he made a foray into the then-burgeoning motion picture industry His old friend Vaughan Glaser again played a key role in introducing Cobb to the movies. The year was 1916, and Glaser now was the vice president of the Sunbeam Motion Picture Corporation, a newly-formed, New York City-based film production outfit.

Sunbeam had been incorporated in March “to manufacture, sell, and deal in and with motion picture films of all kinds.” Its capitalization was listed at $2.5 million, and the company soon began running newspaper ads soliciting investors to purchase stock at $5 per share. One such ad in the July 12 issue of the Pittsburgh Gazette Times announced “Work on the first production of the Sunbeam Motion Picture Corporation is well under way in New York City . . . The production on its release will make Sunbeam’s first bow in the picture world. . . . When you see this picture you will congratulate yourself on your connection with this company.”

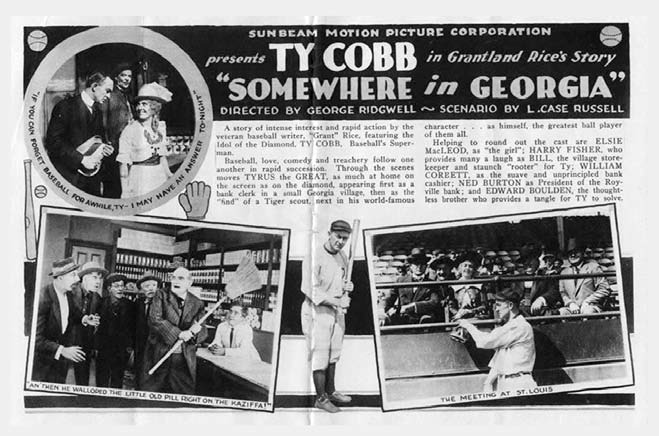

Glaser viewed the project as tailor-made for Cobb. The title was Somewhere in Georgia, and it was based on a story by Georgia native Grantland Rice, then a New York Tribune columnist. At the helm would be George Ridgwell, an actor-writer who amassed over 70 screen directorial credits between 1914 and 1929. (In the Sunbeam stock solicitation ad, Ridgwell was quoted as promising that the film “will mean standing room only, wherever exhibited, and it will be a MARVEL of completeness and technique.”) The scenario would feature the ballplayer as “Ty Cobb,” a poor but upright bank clerk and part-time ballplayer who competes with a smarmy cashier for the affection of the boss’s daughter. Meanwhile, his ball playing is scrutinized by the Detroit Tigers and he is signed to a professional contract. After returning home to entertain the locals, he is momentarily foiled by some ruffians in the employ of his rival before winning both the climactic game and the girl.

Glaser assuaged Cobb’s fears of screen acting by explaining that shooting a film was entirely unlike touring in a play. There would be no traveling from city to city, no repeating his performance, no gladhanding and posing with well-wishers. Plus, he would walk away with what Cobb biographer Charles C. Alexander described as “at least as much as he got for his theatrical tour in 1911-12.” According to Al Stump, the Cobb biographer who also ghostwrote his autobiography, his Somewhere in Georgia salary far-surpassed $10,000. It was $25,000, plus expenses.

In October 1916, Cobb was one of several dozen major leaguers who earned extra bucks by playing in a series of exhibition games. After one in New Haven, he headed to New York to star in Somewhere in Georgia. Despite its title, the movie was not filmed somewhere — or anywhere —in Georgia. Given its status as a novice enterprise, Sunbeam wished to shoot the film as close to its West 42nd Street Manhattan headquarters as possible and in the shortest amount of time.

The entire six-reel feature was filmed in two weeks and, by all reports, the shoot went smoothly. Alexander noted that the ballplayer “again took his work seriously. Director George Ridgwell commented on how studiously [sic] Cobb was, how he seemed to anticipate instructions. ‘I’ve never had to tell him more than once what I wanted done,’ Ridgwell said. The main problem had to do with Cobb’s love scenes with Elsie MacLeod, playing his love interest. Cobb was quite timid, reported Ridgwell, so much so that it had been necessary to direct those scenes with extreme delicacy.”

Al Stump noted in his Cobb biography that, during the shoot, Douglas Fairbanks stopped by to say hello. According to Stump, the ballplayer and the actor, who then was cementing his status as a silent screen immortal, became friendly and Fairbanks “suggested that he direct a first-class movie on Cobb’s real life. Nothing ever came of it.”

MARKETING THE PRODUCT

Somewhere in Georgia was advertised as Sunbeam’s “initial offering to the Motion Picture Trade” in The Moving Picture World, an industry trade publication. In a puff piece which ran on November 11, 1916, the periodical reported that “Cobb has proved since he started to work on his first picture . . . that he is not only valuable because of his world-wide reputation, but because he is a natural born actor.” In the piece, Ridgwell declared, “I will never forget the first scene that Cobb worked in. He seemed to understand what he was to do the moment we set the camera. Well, I was so stunned that I instinctively yelled `Shoot!’ and started on the picture. Every move that Cobb made reminded me of a seasoned actor. And his facial expressions; it seemed that he could be happy and tragic at the same time.”

Cobb’s onscreen presence clearly was the film’s selling point, and was the focus of its publicity campaign. The ad copy that promoted Somewhere in Georgia to exhibitors made the film sound like a cross between Field of Dreams and The Natural, circa 1916:

You know Ty Cobb and you know that everyone, whether a baseball fan or not, will want to see him on the screen.

The Greatest Star of the nation’s Favorite Sport, featured in the People’s Most Popular Amusement, ‘The Movies,’ with a story by Grantland Rice of the New York Tribune, America’s best known Sporting Writer.

Can you see what that combination will mean at the box office?

‘SOMEWHERE IN GEORGIA’ is not merely a vehicle for showing Ty Cobb to advantage. It is a big, vital, interesting story by and for red-blooded human beings; a story of love, ambition and the National Game.

Without Ty Cobb and Grant Rice it would be a big feature. With them it will be a recordbreaker. Ty Cobb is not only the greatest ball player of all time but an accomplished actor as well.

Somewhere in Georgia was marketed on a states rights basis, meaning that it did not have a national distributor. Instead, regional distributors purchased licenses from Sunbeam to show the film. The ad copy concluded, “We will release this picture on the open market. No territory has been sold in advance of this announcement, but hundreds of inquiries have been received. We therefore advise quick action.”

Sadly, no footage from Somewhere in Georgia is known to survive. In fact, more than half of all films from this period are lost. Prints and master materials deteriorated because they were generated on nitrocellulose film stock. In some cases, they were abandoned or destroyed by producers who could not see their future value as commercial entities. Any of these scenarios might explain the fate of the Somewhere in Georgia prints.

Additionally, very little paper material relating to the film exists. In its June 2009 catalog, Lelands.com, a sports auction house, listed what it described as a “never seen before item that will probably never [be] seen again” — a lot consisting of two Sunbeam Motion Picture Corporation stock certificates, dated 1916 and 1917; a Sunbeam brochure; several letters, including one pertaining to the selling of screening rights to Somewhere in Georgia in New England; and, most significantly, a set of eight double-sided eight-by-ten-inch lobby cards, seven of which pictured Cobb. The entire lot was offered for a $10,000 reserve.

Given its states-rights distribution status, Somewhere in Georgia had no discernable release pattern; the film played in venues that were scattered across the country, and indications are that it earned the most limited release. In March 1917, the film first was seen in New York City. The New York Tribune cleverly referenced its six-reel running time by reporting that Somewhere in Georgia “is described as ‘a thrilling drama of love and baseball in six innings.’ It is all of that, and as an actor Ty Cobb is a huge success. In fact, he is so good that he shows all the others up.” In June, the film opened in Rochester, New York, and the Rochester Express labeled it a “good melodrama with comedy touches,” adding that “Cobb’s acting is almost as good as his ball playing.”

Inexplicably, no record exists of the film being screened in Cobb’s home state. “I don’t know if it played in Atlanta, but I doubt it,” reported Ron Cobb, a self-described “distant Georgia cousin” of the ballplayer. “I have been through the Atlanta Journal and Atlanta Constitution for the years Cobb played pretty carefully, and don’t remember seeing anything about it.” While the ballplayer’s College Widow tour earned saturation coverage in the Augusta Chronicle, there is no record in the paper that Somewhere in Georgia played in one of the city’s movie houses—or, for that matter, that the film even existed. Grantland Rice’s column, titled “The Sportlight,” was regularly appearing in the Chronicle. Around the time of the production and release of Somewhere in Georgia, Rice frequently wrote about Cobb, comparing his prowess to Tris Speaker and Shoeless Joe Jackson and making such observations as “Knowing Cobb as we do, we should say that the only element calculated to crush his ambition and break up his determination would be a pine box about seven feet long with the lid nailed over his remains.” But Rice, too, kept mum regarding Somewhere in Georgia.

Not all reviewers were as enamored with Somewhere in Georgia as the critics in New York City and Rochester. The film was lambasted in the June 7, 1917, edition of WID’s, a journal that offered critical analysis and touted the box office appeal of new films. In a summary of the review’s content, the anonymous WID’s critic called Somewhere in Georgia a “very ordinary movie” Under the heading of “Direction,” the reviewer noted that the “atmosphere lacked class and overplaying made [the] entire offering seem ordinary.” The cinematography was “generally poor; occasionally acceptable.” The lighting was “not good.” Of Cobb, the critic observed: “As actor, good ball player, but better than [the supporting cast].”

The WID’s scribe concluded the review by observing:

If your fans are of the intelligent, discriminating community class I’d say that you cannot afford to play this, despite the fact that it would bring you some money. The production is crude from start to finish, the story is ordinary and there is nothing about it to make it entertaining. Naturally there is some interest in watching Ty Cobb trying to appear unconscious of the camera without succeeding very well. . . Even the boob fan will hardly consider this a good picture but they will overlook many of the shortcomings because of the fact that they all understand that the offering has been adjusted to fit the baseball hero’s acting limitations.

Additionally, one highly respected and influential show business figure positively loathed the film. Ward Morehouse, a Savannah native and the longtime Broadway theater critic and New York Sun columnist, labeled Somewhere in Georgia “simply awful” and “absolutely the worst movie I ever saw.”

Variety, the most eminent of all motion picture industry trade publications, also reviewed Somewhere in Georgia. This critique, printed on June 8, was more flattering. While predicting that the film would “make a ten-strike with Young America,” the Variety scribe wrote that the “story holds interest to the extent that those familiar with baseball and Cobb’s life . . . will obtain a lot of fun in watching Tyrus enact the role of a photoplay hero. . . . The story doesn’t matter much. . . . It is one of those Frank Merriwell stories, with Ty doing the Merriwell stuff that catches the young folks.” The reviewer concluded by predicting, “Some sections will fall hard for the film while others won’t care much to have it hanging around. But it has a good, wholesome atmosphere and a real, live-blooded, clean-limbed [sic] athlete for a hero.”

DISAPPOINTING RETURNS

Apparently, not enough sections fell hard enough for Somewhere in Georgia to earn the film a profit. While the actual box office take has been lost in the annals of film history, the fact is that Somewhere in Georgia was the sole film produced by the Sunbeam Motion Picture Corporation. Sunbeam’s only additional involvement in the motion picture business came in 1921, when the company secured the distribution rights to and re-released Rip Van Winkle, a 1914 film originally produced by Rolfe Photoplays and distributed by the Alco Film Corporation.

Given the low profile of Somewhere in Georgia within the realm of the history of the silent cinema, plenty of misinformation exists regarding the film. For example, in his Ty Cobb biography, Dan Holmes noted, “It was the first motion picture featuring an actual athlete as the star, and it was the first widely distributed baseball movie.” Don Rhodes, another Cobb chronicler, wrote, “The film is said to be the first movie starring a major sports figure.” Associated Press writer Larry Rosenthal stated that Cobb was “the first professional athlete to star in a commercial motion film.” The declaration that Cobb “became the first ball player to star in a movie” is listed as a factoid on The BaseballPage.com web site. The same claim is found on dozens of other Internet venues—including Cobb’s official web site. In truth, however, Somewhere in Georgia was not widely distributed. Additionally, before its release, a host of big-leaguers — starting with Christy Mathewson, Frank Chance, Home Run Baker, Hal Chase, and Wally Pipp — top-lined one and two-reel films. Right Off the Bat, a five-reeler starring Mike Donlin and featuring John McGraw, was released in September 1915 — before Somewhere in Georgia had gone into production.

A number of professional ballplayers have had lucrative careers as actors-entertainers-raconteurs. The list begins with Mike Donlin, Rube Marquard, Chuck Connors, Bob Uecker, John Beradino (who played in the majors as Johnny Berardino), and Joe Garagiola. Lou Gehrig acquitted himself nicely in Rawhide (1938), his lone screen appearance. Had he not died so young, he might have enjoyed a second career as a B-Western hero. Babe Ruth starred in the feature films Headin’ Home (1920) and Babe Comes Home (1927) and a short subject, Home Run on the Keys (1936); made a cameo appearance in the Harold Lloyd comedy Speedy (1927); played himself to fine reviews in The Pride of the Yankees; and appeared in a number of instructional films. His larger-than-life, overgrown teddy-bear persona registered well onscreen. If he had not been a ballplayer, he might have made an effective sidekick or foil for any number of screen comedians.

One cannot picture Ty Cobb clowning with the Stooges, cutting it up with Harold Lloyd, or toting a six-shooter and besting Old West varmints in gun battles. After Somewhere in Georgia, he occasionally appeared onscreen in such documentary and instructional short subjects as The Baseball Revue of 1917, Cradle of Champions (1921), Ty Cobb and Grantland Rice Talk Things Over (1930), and Swing With Bing (1940). In the 1950s, he guested on television’s What’s My Line? and I’ve Got a Secret. Easily his most high-profile screen credit was his surprise cameo, along with Joe DiMaggio, Bing Crosby, and Tin Pan Alley songwriter Harry Ruby, in the first version of the baseball comedy-fantasy Angels in the Outfield (1951).

Simply put, the Georgia Peach had neither the need nor the desire to emulate Donlin, Marquard, and the others. His appearances in The College Widow and Somewhere in Georgia were his lone forays into the world of stage and screen acting.

ROB EDELMAN, author of more than ten books, including “The Great Baseball Films: From Right Off the Bat to A League of Their Own” (Carol, 1994) and “Baseball on the Web” (MIS Press, 1998), teaches film history at the University of Albany–SUNY.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Audrey Kupferberg; Ron Cobb; Tim Wiles, Jim Gates, and Freddy Berowski, National Baseball Hall of Fame Museum and Library; Billy Rose Theatre Collection, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

SOURCES

Books

Alexander, Charles C. Ty Cobb. New York: Oxford University Press, 1984.

Cobb, Ty, with Al Stump. My Life in Baseball, the True Record. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1961.

Edelman, Rob. The Great Baseball Films: From Right Off the Bat to a League of Their Own. New York: Citadel Press, 1994.

Hanson, Patricia King, ed. The American Film Institute Catalog of Motion Pictures Produced in the United States: Feature Films, 1911–1920. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988.

Holmes, Dan. Ty Cobb: A Biography. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2004.

Laurie, Joe, Jr. Vaudeville: From the Honky Tonks to the Palace. New York: Henry Holt, 1953.

McCallum, John D. Ty Cobb. New York: Praeger, 1975.

Rhodes, Don. Ty Cobb: Safe at Home. Guilford, Conn.: Lyons Press, 2008.

Stump, Al. Cobb: A Biography. Chapel Hill, N.C.: Algonquin Books, 1994.

Periodicals

Clarkson, James. “Ty Cobb May Demand $50,000, Talks of Three-Year Contract.” Chicago Examiner, 5 January 1912.

E.A.B. “The Play Last Night.” Augusta Chronicle, 19 November 1911, 11.

Edelman, Rob. “Baseball, Vaudeville, and Mike Donlin.” Base Ball: A Journal of the Early Game 2, no. 1 (2008): 44–57. —–—. “The Baseball Film to 1920.” Base Ball: A Journal of the Early Game 1, no. 1 (2007): 22–35.

“Mark.” “Somewhere in Georgia.” Variety, 8 June 1917, 22.

Mathewson, Christy. “Ball Player Must Avoid Diversions.” New York Times, 11 December 1919, 54.

Rosenthal, Larry. “Life, Myth of the ‘Georgia Peach’ Examined in Play.” Associated Press, 18 March 1989.

Thomas, Ron. “Toronto Man Recalls Ty Cobb as an Actor.” Toronto Daily Star, 19 July 1961.

“American League Notes.” Sporting Life, 1 July 1911, 13.

“American League Notes.” Sporting Life, 25 November 1911, 13.

Atlanta Journal, unheadlined article, 24 November 1911.

“Avon Theater.” Rochester Express, 5 June 1917.

“Baseball Players Fined.” New York Times, 9 December 1916, 8.

“Cobb as Actor.” Sporting Life, 9 September 1911, 24.

“Cobb Makes Debut in College Widow.” Augusta Chronicle, 6 November 1911, 9.

“Crude Meller Poorly Played, Featuring Ty Cobb.” WID’s, 7 June 1917, 367.

“Fans’ Applause Helps.” Los Angeles Examiner, 22 December 1911.

“First Night on Stage Was Like a Nightmare.” Pittsburgh Leader, 3 December 1911.

“Governor Woodrow Wilson Spent Yesterday in Home of Boyhood.” Augusta Chronicle, 19 November 1911, 4.

“He Remembers When the Road Wandered On and On Forever.” New York Herald-Tribune, 10 July 1938.

“Lyceum Theater.” Cleveland Leader, 9 January 1912.

“Manhattan’s Ball Dope.” Augusta Chronicle, 18 December 1911, 6.

Moving Picture World, advertisement, 28 October 1916: 504–5.

New Incorporations.” New York Times, 23 March 1916, 19.

Pittsburgh Gazette Times, advertisement, 12 July 1916.

“Sidelights on Tyrus Cobb.” Baseball Magazine, March 1912, 53.

“Ty Cobb, Actor and Ball Player, Surrounded By Members of Company.” Atlanta Constitution, 24 November 1911.

“Ty Cobb An Actor.” Toledo Blade, 28 August 1911.

“Ty Cobb Gives Views on Ticket Scalping As Well As Acting.” Toledo Times, 7 December 1911.

“Ty Cobb in ‘The College Widow.’” Augusta Chronicle, 12 November 1911, 3.

“Ty Cobb in ‘The College Widow.’” Augusta Chronicle, 14 November 1911, 8.

“Ty Cobb in ‘The College Widow.’” Augusta Chronicle, 16 November 1911, 8.

“Ty Cobb in ‘The College Widow.’” Augusta Chronicle, 17 November 1911, 9.

“Ty Cobb, in ‘The College Widow,’ at the Grand Nov. 18.” Augusta Chronicle, 11 November 1911, 8.

“Ty Cobb Is Going On Stage in New Version of ‘College Widow.’” New Jersey Review, 26 August 1911.

“Ty Cobb Paying Before Camera.” Moving Picture World, 11 November 1916, 879.

“Ty Cobb, Poor Actor, Good Ball Player.” New York Times, 13 June 1915, 83.

“Ty Cobb Scores Hit.” Pittsburgh Leader, 5 December 1911.

“Ty Cobb Suggests Plan to Give Talent a Chance.” Pittsburgh Leader, 1 December 1911.

“Ty Cobb Today.” Augusta Chronicle, 18 November 1911, 3.

“‘Ty’ Cobb Will Be Entertained.” Augusta Chronicle, 11 November 1911, 7.

“Ty Cobb’s Horse-Sense.” Variety, 6 January 1912.

“Ty Cobb’s Screen Hit Wins Game, Foiling Villain.” New York Tribune, 8 March 1917.

“Tyrus Raymond Cobb.” Kalamazoo Telegraph, 9 December 1911.

“Tyrus Raymond Cobb (At the Atlanta).” Atlanta Constitution, 19 November 1911.

“When Ty Cobb Comes.” Augusta Chronicle, 13 November 1911, 6.

Internet

Baseballtips.com. http://baseballtips.com/tycobb.html.

BBC.com. www.bbc.co.uk/dna/h2g2/a1118648.

Internet Broadway Database. www.ibdb.com/index.php.

Internet Movie Database. www.imdb.com.

Lelands.com. https://www.lelands.com/bid.aspx?lot=331&auctionid=905.

NCAA.com. www.ncaa.com/sports/m-footbl/spec-rel/032608abj.html.

The Baseball Page.com. www.thebaseballpage.com/players/cobbty01.php.

The Official Web Site of Ty Cobb. www.cmgww.com/baseball/cobb/know.html.

Ty Cobb Museum. www.tycobbmuseum.org.