The Windy City–Collar City Connection: The Curious Relationship of Chicago’s and Troy’s Professional Baseball Teams (1870–82)

This article was written by Jeff Laing

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in Chicago (2015)

Both Chicago and Troy fielded strong baseball nines in the baseball’s post-Civil War pioneer days. With the advent of professional baseball after the 1868 season, the fortunes of Chicago and Troy became intertwined by happenstance and the loosely-knit structure and highly unstable nature of nineteenth century baseball. Both cities played a major part in the ebb and flow of the national pastime as baseball organized itself into professional leagues.

The first baseball dealings between these cities began acrimoniously. In 1870, just prior to the establishment of the first professional organization—the National Association of Professional Base Ball Players, or National Association (NA)—the White Stockings formed as a professional club. The upstart team claimed a national championship using several former members of the Unions of Lansingburgh (Troy) 1, including catcher Mart King, first sacker Bub McAtee, and right fielder Clipper Flynn. 2

Tensions continued to rise between the cities when Chicago signed notorious Trojan serial revolver and win-at-all-costs scalawag Bill Craver, 3 who was in turn enticed back to the Collar City after vague allegations of “contract violations” by the Chicago club.

It is, therefore, no surprise that the most bitterly fought game of the 1870 season occurred in Upstate New York that June 23 between the White Stockings and the Haymakers. Following a devastating loss to the Forest City team of Rockford, IL, and with the hated White Stockings’ imminent arrival in the Collar City, Troy management raised $5,000 to bolster its roster. Among other solid ball players, the Haymakers signed pitcher John McMullen and center fielder Tom York. Chicago filed a protest, stating that the newly signed players had taken the field with other NA teams within the past 60 days, a direct violation of the group’s bylaws. After much grandstanding by both teams, the game was eventually played with Chicago winning 35–21. 4

Chicago ended its season on a high note. On November 1, 1870, before 6,000 fans at Chicago’s Dexter Park, the White Stockings won the national championship in a bitter contest against the Mutual club of New York, a game which ended with a disputed technical decision. Mutuals pitcher Rynie Wolters stalked off the mound after walking the bases loaded with his team leading 13–12, claiming that the umpire was biased. After the Mutual club refused to take the field, the game reverted to the last completed inning, after which Chicago had led 7–5.

This decision gave the White Stockings the “title” amid the protests of the Mutuals, who continued to proclaim themselves champions. 5

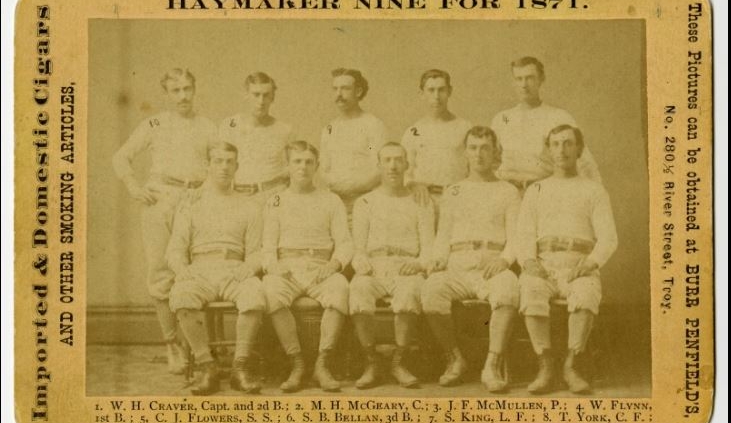

The 1871 Haymakers, with manager/second baseman Bill Craver (front center) and slugger Lip Pike (back center).

The Craver contretemps continued into the 1871 season, with Chicago refusing to play the Haymakers if Craver was in the lineup and, further, not allowing the Troy club to play other teams at Chicago’s Union Base Ball Grounds. Moreover, the White Stockings withheld past gate receipts due the Trojan management:

The White Stockings have informed the Haymakers that they will not suffer Craver to play in any game against them, nor will they allow the Haymakers to play any other club on the Chicago grounds if Craver is one of the nine…. The Chicago Times takes ground against the White Stockings for retaining the Haymaker money, and very properly stigmatizes the act as robbery. It says that a corporation may escape punishment for doing what an individual [would suffer]. 6

The Chicago-Troy relationship improved somewhat following the October 8, 1871, Chicago Fire, which destroyed the White Stockings’ ballpark and equipment. Stranded on the road, Chicago split a pair of games at Troy on October 21 and 23; two other games were rained out. On October 30, at the Brooklyn Union Grounds, the White Stockings lost the NA’s first pennant, falling 4–1 to the Athletics of Philadelphia. On November 2, the White Stockings played a benefit game in Troy, an anticlimactic end to the season and to the year’s heated rivalry. 7

Prior to the 1872 NA season, Troy looked west to build a winner. With Chicago not fielding a professional team in 1872 or 1873, Troy rebuilt its roster with Windy City imports: Jimmy Wood, the team captain and second baseman, and George Zettlein, a hard-throwing pitcher. The pair led the Haymakers to their best-ever professional baseball record (15–10).

Though only playing in Troy for a few months, Wood and Zettlein are considered all-time Haymakers. Jimmy Wood was a batting star for the 1872 club, batting a robust .336 with a .558 slugging percentage. Having played with many Trojans on the 1870 White Stocking championship club, Wood was certainly aware of the city’s baseball heritage. This is presumably one reason he was chosen to be captain (i.e., manager) of the 1872 squad. Unfortunately, Wood was considered a poor manager due to his disorganization and foul temper. His NA managerial record was 105–99. 8

Wood, a longtime admirer and associate of fire-balling George Zettlein, had first recruited the hurler for the 1870 White Stockings. Zettlein led NA pitchers in earned run average (2.73) in 1871 while compiling an 18–8 record. In 1872, he fashioned a 2.16 ERA and 14–8 mark for the Haymakers. By 1875, however, Zettlein was mired in game-fixing controversies and Wood had accused him of not giving his best effort in the box. 9

The 1872 Haymakers played their last NA contest on July 23, winning a road game against the Middleton, CT Mansfields. Troy’s management could not meet payroll, leading the club’s players to disband. They attempted to return as a “cooperative” club for one desultory loss on July 30. Many of Troy’s players, including Wood and Zettlein, signed with the woeful Eckfords of Brooklyn for the remainder of the 1872 season. Troy played an independent schedule through 1878. 10

Chicago’s baseball fortunes looked up in 1874 when the club re-entered the NA. While the White Stockings were mediocre on the field, team Secretary William Hulbert began an ambitious campaign of signing star players; he inked Albert Spalding, Cap Anson, and Deacon White prior to the conclusion of the 1875 season in direct violation of NA regulations.

Though Hulbert correctly assessed the NA as a disorganized group with a doubtful financial future, a high tolerance of boorish behavior by fans and players, and a nod-and-wink policy of suspicious betting patterns, he also acted with extreme self-interest in 1876 when he founded the National League (NL). Hulbert was supported in this action by the moral authority of Cincinnati baseball pioneer Harry Wright and the media support of editor Lewis Meacham of the Chicago Tribune, but not by his fellow owners; in fact, Hulbert acted just before being confronted and penalized by NA ownership.

In a direct conflict of interest, Hulbert became the NL’s second President following the 1876 season, taking over from an uninterested Morgan Bulkeley while remaining Secretary of the White Stockings. The Chicago businessman further codified and institutionalized financial control of the game, offering management “geographical exclusivity” and running the league as a monopoly wherein the owners determined which clubs’ applications would be accepted. Hulbert believed that if he could hire the most talented players, he could eliminate rival leagues from luring away talent, thus lowering team payrolls and increasing ownership profits.

Hulbert was also unforgiving in dealing with management malfeasance. He believed establishing baseball’s integrity was the key to increasing fan support and gate receipts. He expelled the Philadelphia and New York City franchises for not completing their 1876 schedules. In 1877 and 1878, Hulbert ran a shaky six-team NL, barely surviving a major game-fixing scandal by Louisville in 1877. 11 The Chicago magnate eagerly anticipated making major changes to the league for 1879.

During the 1878 off-season, Troy reestablished its checkered relationship with the Windy City by applying for entry to the NL. Hulbert accepted the Trojans’ application even though the Collar City did not meet the 75,000 population requirement for new franchises. He simply persuaded the board of directors to alter a league rule to favor Troy’s application and even allowed the Haymakers to continue playing exhibition games (for money) against its geographical rival, Albany:

The entry into the National League of the [Troy] Trojans [known officially as the Troy Citys and unofficially as the Haymakers] was greeted with enthusiasm by its supporters, but it was not without controversy. Part of the Trojans’ financial success stemmed from their games with their neighbors across the Hudson River in Albany. Troy requested the inclusion of the Albany ball club into the National League, a request which was denied because scheduling problems which would result from a nine-team league. Additionally, the National League’s territorial rights rule prevented more than one team per city and no games between cities fewer than five miles apart. [Troy and Albany are separated by 4.75 miles.] This rule prevented Troy and Albany from playing exhibition games against each other. Eventually, the Trojans settled for an amendment of the territory rule, reducing the gap from five miles to four and allowing them to play exhibition games against their Capital District neighbors. 12

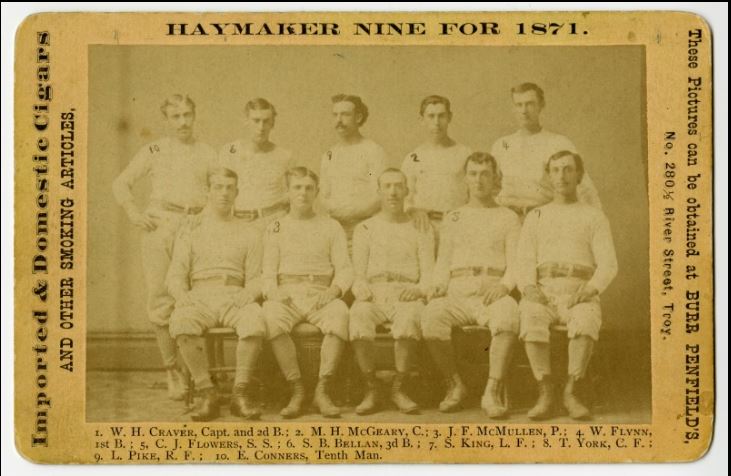

The 1881 and 1882 Troy Trojans had three Hall of Famers: catcher Buck Ewing (rear, right) and hurlers Tim Keefe (next to Ewing) and Mickey Welch (rear, left).

Influenced both by his continued animus to Philadelphia and New York City and his knowledge of Troy’s long and storied history with the national pastime, Hulbert shepherded the Haymakers franchise. While Troy’s tenure in the NL was marked by spotty attendance and increased financial difficulties, Hulbert defended the Trojans against attempts to replace them with a team from a larger market.

Hulbert passed away just prior to the 1882 season at a time when NL owners felt threatened by the establishment of the American Association (AA).The magnates were fed up with the weak financial status of the Trojan club and its cloudy future and eventually ousted the Haymakers on September 25, 1882, by an ownership vote of 6–2. This vote violated the NL’s own constitution, but the owners chose anyway to admit a New York City-based entry for the 1883 season. 13

Troy fought the expulsion by threatening to sue the league for $5,000 for the costs of refurbishing its new West Troy (Watervliet) Ballpark. The Haymakers also threatened to apply to enter the American Association in 1883. Placated by promises of a large number of exhibition games in Troy by NL teams and of possible reinstatement into the NL at some unspecified future date (neither of which ever came to fruition), Haymakers management never followed through on the proposed lawsuit or AA application. The Collar City had been removed from major league baseball, never to return.

The conclusion of the 1882 NL season ended the curious relationship of the Chicago and Troy professional baseball clubs and forever marked the divergence of the baseball fortunes of both cities. The Windy City became an industrial and cultural force as the railroads expanded westward and capital and industry moved to newer and larger markets closer to necessary natural resources. The Chicago of the 1880s surpassed, in importance and influence, smaller, gritty Northeastern cities such as Troy which depended on hydroelectric power and a skilled force that eventually emigrated west to follow superior economic opportunities. 15

The fortunes of Chicago’s and Troy’s nineteenth century baseball franchises reflect the growth and development of both populations. While Chicago still boasts two flourishing major league franchises, Troy has remained without a major league club for 133 years.

JEFF LAING lives in Santa Fe, New Mexico and is the author of “Bud Fowler: Baseball’s First Black Professional.”

Notes

(1) Troy’s professional baseball club was originally named the “Union Base Ball Club of Lansingburgh,” though they were popularly referred to as the “Troy Haymakers” as early as 1866. When Troy entered the National Association in 1871, the club was officially called the “Haymakers” until its demise in 1872. When the Haymakers entered the National League in 1879 they became the “Troy Citys” and/or the “Troy Trojans” but were commonly referred to in the media and among supporters as the “Haymakers.”

(2) Patrick Mondout, “1870 Baseball Season,” www. Baseballchronology.com .

(3) Bill Craver was among pioneer baseball’s most notorious figures both on and off the field. He was banned for life from the NL in 1877 for his involvement and inaction in the Louisville Grays hippodroming scandal. Later that year, Craver’s tarnished reputation led to his banishment by his hometown Haymakers, who had often provided safe passage during his career. After his forced retirement from baseball, Craver became a patrolman in Troy. Craver’s batterymate Cherokee Fisher also signed with the White Stockings, but pocketed their monies and never played a game for Chicago ( Troy Daily Whig, 13 July 1870.)

(4) Fort Wayne (IN) Daily Democrat, 28 June 1870, p. 11; David Pietrusza, “Capital Region Baseball Timeline, Part I: 1819-1899,” http://www.davidpietrusza.com/capital-reg-baseball-1.html, p. 4; Peter Morris, “Union Base Ball Club of Lansingburgh/Haymaker of Troy” http://archive.is/yuZ3 V, p. 11. The extent to which the Haymakers were committed to improving their club for the 1870 season, no matter the cost, is reflected in the six-week signing of catcher Pat Dockney, a noted carouser and serial revolver. (William J. Ryczek, When Johnny Came Sliding Home: The Post-Civil War Baseball Boom, 1865-1870, (Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, 1998), pp. 143-144.)

(5) “1870 Baseball Season,” Baseball Chronology.

(6) Troy Daily Whig, 8 July 1870.

(7) “1871—National Association,” Sean Lahman Baseball Archives. www.sean-lahmans-baseball-archive.com. (Accessed 12/12/2013); James L. Terry, Long Before the Dodgers: Baseball in Brooklyn 1855-1884 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, 2012), p. 99; John Thorn, Baseball in the Garden of Eden: The Secret History of the Early Game (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2011), p. 152; William J. Ryczek, Blackguards and Red Stockings: A History of Baseball’s National Association, 1871-1875 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, 1992), p. 64.

(8) Ryczek, Blackguards and Red Stockings, p. 134; “Jimmy Wood,” http://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/W/Pwoodj106.htm.

(9) “Offered Him $1,000 to Throw the Game” Troy Haymakers Archive, pp. 1-4. http://baseballhistorydaily.com/tag/troy-haymakers.; “George Zettlein,” http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/z/zettlge01.shtml; “1871,” 1871—The Baseball Chronology, www.baseballlibrary.com/chronology/byyear.php?year=1871.

(10) Peter Morris, William J. Ryczek, Jan Finkel, Leonard Levin and Richard Malatzky (editors), Baseball Founders: The Clubs, Players and Cities of the Northeast That Established the Game (Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, 2013), pp. 174-175.

(11) Michael Haupert, “William Hulbert,” SABR Biography Project, pp. 1-4

http://sabr.org/bioproj/d1d420b3; William E. Eakin, “William A. Hulbert,” Robert Tiemann, ed., Nineteenth Century Stars (Phoenix, AZ: Society of American Baseball Research, Inc., 2012), pp. 135-136.

(12) Ray Kim, “When Troy Was a Major League City,” p.4 http://www.empireone.net/~musicman/troyball.html.

(13) Troy Daily Times, 23 Sept. 1882.

(14) Lancaster (PA) Daily Intelligencer ; Syracuse Morning Standard ; and New York Times, 26 Sept. 1882.

(15) Deborah Nazon, Brownfield’s Redevelopment and Competitive Advantage Theory: Urban Revitalization and Stakeholder Engagement in South Troy, NY (Ann Arbor, MI: ProQuest UMI Dissertations Publishing), 2007), pp. 45 and 49-50; George Baker Anderson, “History of Troy New York” in Landmarks of Rensselaer County (Syracuse, NY: D. Mason and Company, 1897); Steven M. Gelber, “Working at Playing: The Culture of the Workplace and the Rise of Baseball,” Journal of Social History , 16, 4 (Summer 1983), p. 16; Peter Morris, “Union Base Ball Club of Lansingburgh/Troy Haymakers,” in Peter Morris, William J. Ryczek, Jan Finkel, Leonard Levin and Richard Malatzky (editors), Base Ball Pioneers, 1850-1870: The Clubs and Players Who Spread the Sport Nationwide (Kindle edition) (Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, 2012) loc. 1962–1984.