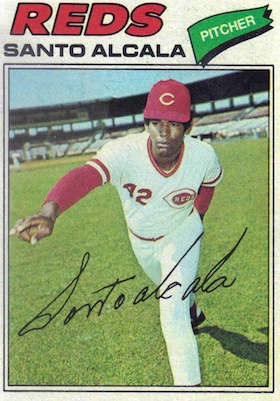

Santo Alcala

Santo Alcala was born and raised in the so-called “baseball capital of the world,” San Pedro de Macoris in the Dominican Republic.1 At the age of 16, the tall righty pitcher became a professional baseball player. He won 11 games and a World Series ring with Cincinnati’s Big Red Machine in 1976—his one year of glory. After just one more season, he was out of the major leagues at the age of 24, never to return. Arm problems were a factor, but as one report put it after Cincinnati traded Alcala in 1977, “The 6’6” Dominican throws bullets but has control problems.”2

Santo Alcala was born and raised in the so-called “baseball capital of the world,” San Pedro de Macoris in the Dominican Republic.1 At the age of 16, the tall righty pitcher became a professional baseball player. He won 11 games and a World Series ring with Cincinnati’s Big Red Machine in 1976—his one year of glory. After just one more season, he was out of the major leagues at the age of 24, never to return. Arm problems were a factor, but as one report put it after Cincinnati traded Alcala in 1977, “The 6’6” Dominican throws bullets but has control problems.”2

Alcala pitched professionally in the United States, Canada, the Dominican Republic, and Mexico. Even so, his name is unknown to most American baseball fans. Santo Alcala has largely disappeared from public view in the U.S.

Santo Aníbal Alcalá was born on December 23, 1952. His given name typically has an ‘s’ on the end in Spanish. Alcala’s wife, attorney Yolanda Mejía, explained. “It ought to be Santos, but apparently my mother-in-law pronounced it ‘Santo’ when it was registered, so that is his name officially.”3 Nonetheless, Dominican and Mexican sources typically show Santos, as did certain U.S. stories during his playing career. Note also that in Spanish, the last syllable of his surname is accented. In the U.S., it was typically pronounced AL-cala.

Also noteworthy is how Alcala is known by his mother’s family name. His father was Juan Aníbal Solano, who worked at Central Romana, a sugar-cane factory about 20 miles east of San Pedro de Macoris. Santo’s mother, Anadina “Ana” Alcalá, was Solano’s common-law wife. Santo was their only child; he had two half-brothers (Mauro and Epifanio) and a half-sister (Milagros) from Ana’s previous marriage to a man named González. When Santo was born, he was registered under the name of Alcalá; later everyone agreed that changing the records meant too much time and trouble.4

Alcala’s hometown is located in the sugar-cane producing area of his country, on the Caribbean coast about 50 miles east of Santo Domingo. The motto of this baseball hotbed is seis-cuatro-tres, or 6-4-3, scorebook notation for shortstop to second to first. San Pedro is frequently referred to as the cradle of shortstops. On a per capita basis it has produced probably as many major-league shortstops as any other city in the world. However, it has furnished the majors with players at all positions, including pitchers. In 1969, Santiago Guzman became the first native of San Pedro to pitch in the major leagues; he was followed in 1976 by Joaquin Andujar and Alcala. By 1985 The Sporting News heralded the area as “Baseball’s Secret Treasure,” quoting Ralph Avila, a Los Angeles Dodgers official, as saying, “San Pedro de Macoris is . . . the best baseball town in the world.”5

During Alcala’s youth, boys throughout much of the Caribbean area aspired to become professional baseball players. They played in the streets or on vacant lots, often with homemade balls and bats. Because many youngsters saw baseball as their only possible route from poverty, motivation was intense. Out of the thousands who tried, several hundred have succeeded. The Dominican Republic has sent more players to the major leagues than any other country outside the United States.

When Alcala was growing up, he and his fellow townsmen had an advantage over youngsters in most Caribbean locales. San Pedro de Macoris had seven sugar-cane factories. The sugar-cane season lasted only three months, but the owners had to care for their employees and their families all year. So the factories built ball fields, provided equipment, and paid instructors. The kids flocked to those ballparks to practice long hours every day. Everyone wanted to play baseball to escape the cane fields or factories.6

Though Alcala’s family was not well off, he lacked nothing; he didn’t have to work as a child and could devote himself to sports. He spent much time on the field, the running track, or in the gym.7 He graduated from high school at Liceo José Joaquín Pérez in 1968 at the age of 15.8 (At that time Dominican public education consisted of six years of primary school, followed by four years of high school.)

Alcala’s original position in baseball had been first base, but he converted to pitcher in 1969. His strong arm impressed Pedro González, the third big-leaguer from San Pedro de Macoris, who ran an amateur league there.9 (It was only in 1973 that major-league teams began to open baseball academies in the Dominican Republic.10) Just a couple of months later, Alcala signed his first professional contract. He had already reached his full height (listed as either 6-feet-5 or 6-feet-6) but then weighed just 170 pounds. That year the Reds also signed Joaquin Andujar, who was just two days older than Alcala. The two friends spent much of their minor-league careers together.

Nearly 40 years later Alcala told a Cincinnati reporter about his signing experience. “Things were different back then,” Alcala said. “The scout who signed me drove over to San Pedro de Macoris and said, ‘C’mon, we’re going to Santo Domingo to watch you throw.’ I said, ‘OK’. I’d never been to the capital before. I threw for him, about 20 pitches, and he said, ‘Sorry. You do not throw hard enough for me to sign you.’ No radar gun, just his eyes. I wanted to be a professional. We didn’t have much money. I said, ‘Give me the ball again.’ After I got done, he said, ‘How about $3000?’ I said, ‘I’ll take it.’” This article gave the scout’s name as Rafael Campino, but Dominican sources show it was Wilfredo Calviño, which fits with the record. Calviño also signed Andujar.11

The Reds assigned both young hurlers in 1970 to their farm team in the Gulf Coast League. Alcala posted a record of 4-6, with an ERA of 3.00. The following year he pitched mainly in relief for the Sioux Falls Packers in the Class A Northern League, and wildness (36 walks in 41 innings) fueled a 5.27 ERA. Still in his teens, Alcala broke into his homeland’s winter league in the winter of 1971-72. He joined the Escogido Leones and would pitch with that club for five subsequent winters.

Alcala started the 1972 season with the Key West Conchs in the Class A Florida State League. He went to the unaffiliated team on loan because the Reds organization thought he would be more comfortable playing under Spanish-speaking manager Pancho Herrera.12 Although Alcala had a losing record with Key West (7-14), he showed enough promise to earn a late-season promotion to the Trois-Rivières Aigles in the Class AA Eastern League. His control was much improved, yet he still struck out nearly a batter an inning. Alcala pitched for the Canadian team again in 1973, going 7-13, 3.93. The Reading (Pennsylvania) Eagle gave a good sense of that season: “Santo Alcala. Great prospect. Big strong prospect.” He’d already beaten the Reading Phillies twice that year, allowing just one run in each game, and was on his way to a third win over them after firing seven shutout innings. “Alcala was putting that good fastball and hard slider exactly where he wanted them.” But he came unglued in the eighth after walking the leadoff man and throwing a sacrifice bunt into center field. “Then he just tried to blow it by us,” Reading catcher Jim Essian observed. “He lost his poise and rhythm.” Reading won, 6-1.13

Alcala continued to develop at home in winter ball. After viewing him pitch for Escogido in the 1973-74 season, Chief Bender, the Reds director of player development, gave the press a glowing report on the prospect’s progress.14 Indeed, Alcala became the league’s Pitcher of the Year, notable for a relief pitcher (as he was then used). Largely on Bender’s recommendation, the Reds invited Alcala to their spring training site in Vero Beach in 1974; although he pitched well, the Reds had a full staff and reassigned him to the minor leagues on April 3. He spent the next two seasons with Cincinnati’s top affiliate, the Indianapolis Indians of the Class AAA American Association. Alcala tied with Pat Darcy for the most wins (12) for the Indians in 1974. On August 31, he pitched a four-hit 1-0 shutout against Iowa and clinched the AA East title. Alcala started two games for the Indians in the AA championship series against the Tulsa Oilers, winners of the AA West. He pitched well in both games, but came away with no decisions. Both his starts, the second and sixth games, were lost in extra innings. Tulsa won the series four games to three.

Alcala led the Indianapolis staff in 1975 with 13 wins against 12 losses. He ranked second in the American Association in both wins and earned run average (2.76). Two of his games that season deserve special mention. On August 12 he hooked up with Tom Brennan of the Oklahoma City 89ers in a memorable pitchers’ duel. Brennan pitched a one-hitter, but Alcala came out on top by pitching a two-hit shutout; the Indians won, 1-0. Later that month (August 29) as the Indians defeated the Omaha Royals, 2-1, Alcala got all of his seven strikeouts on called third strikes. “He was throwing fast balls on the knees and right on the corner,” Omaha’s Ray Busse said. “It was one of those times all you can do is tip your hat and say ‘More power to you, buddy.’”15

Pat Zachry and Alcala, the two best pitchers in the Reds’ farm system, were kept on the major-league roster during the 1976 season because they were out of options. If they had been returned to the minors, they would have become eligible for the next winter’s Rule 5 draft. They appeared to be ready for the majors, but Reds pitching coach Larry Shepard lamented the lockout that delayed the opening of the spring training camps. “Of course, you can’t really say they are (ready) until they’ve been given a good test,” he said.16

Shepard needn’t have worried. Alcala didn’t need spring training to get in condition to pitch. He had kept himself in excellent shape pitching for Escogido. He and Zachry both made significant contributions as the Reds defended their world championship. By that time Alcala had filled out: his baseball cards then listed him at 220 pounds. He made his major-league debut at Riverfront Stadium on April 10, 1976. The 23-year-old relieved Jack Billingham in the sixth inning with the Reds leading the Houston Astros, 8-4. Alcala couldn’t get anybody out. He gave up three earned runs on four straight hits and left the game with the Reds’ lead cut to 8-7. Rawly Eastwick put out the fire, and the Reds went on to win, 13-7.

After four relief appearances, Alcala made his first big-league start at Wrigley Field on May 8. He got off to a terrible start, walking three men in the first inning, all of whom scored on two force outs and a single. But he recovered nicely and gave up only one more hit in seven innings of work and left the game with a 10-4 lead. The Reds won the game, 14-4, and Alcala earned the first win of his major-league career. He won 10 more games that season, against only four losses. His .733 winning percentage, despite an ERA of 4.70, reflected support from the Big Red Machine, which scored an average of 6.1 runs in his 21 starts. Alcala had three complete games and one shutout, and made nine relief appearances during the season.

Again Alcala’s control was a big issue; he walked 67 in 132 innings pitched in 1976. Yet in his shutout of the Mets at Riverfront on May 15, the high point of his big-league career, he walked just one and struck out nine. Three of the four hits he allowed were doubles, but the Mets failed to get any of them home.

After Alcala won his fifth straight start (on May 30, at home over the Dodgers) one wire service reported, “Two years ago he was considered too timid to survive in the major leagues . . . but he has matured rapidly.” Alcala said simply, “I’m not afraid of anybody anymore.”17 This fits with the observations of Malcolm Allen, who has been writing a biography of Joaquin Andujar. Alcala’s name came up often in Allen’s research. “Over and over I heard ‘gentle giant’ and that the Reds wished he was tougher, like Andujar.” At his best, though, Alcala had a catchphrase that sounded like Andujar: “My fastball, she is terrific.”18

Fellow Dominican Cesar Geronimo, Alcala’s roommate on the road, claimed Alcala was the club’s champion sleeper. “That Santo loves to sleep . . . 12 to 14 hours every day. He hates day games,” Geronimo said, adding, “When you sleep a lot, you’re happy. Unhappy people and people who worry can’t sleep.”19

As the number five starter on the Reds’ pitching staff, Alcala made no postseason starts, nor was he needed in relief. The Reds swept the Philadelphia Phillies in the National League playoffs and the New York Yankees in the World Series.

During the spring of 1977 rumors were rife that Alcala was on the trading block. Apparently the Cincinnati brass gave up on Alcala’s ever becoming a consistent winner. The long-rumored trade took place on May 21. The Reds shipped Alcala to Montreal in exchange for two players to be named later, pitchers Shane Rawley and Angel Torres. Alcala took issue with the way the Reds had treated him:

“When you play baseball, you have to be relaxed. I not relaxed. Sometimes I be afraid. I have to win all my games or I out of the rotation. There was a lot of pressure on me. Last year, one time they take me out of the rotation for no reason. I do bad in the beginning of last year. I pitched relief and I never pitched relief before . . . I say nobody care about me.”

But he was happy about the move. “They trade me. Good for me. This is my life. I try to do good over there [at Montreal]. I have a long way to go. I know it. Now I go to mound every fourth day and I learn a little bit more.”20

Montreal manager Dick Williams welcomed the deal and planned to give Alcala a start on May 27. He also said why he thought the Expos got Alcala for just future considerations. “Once [Reds manager] Sparky Anderson loses faith in a pitcher, then that pitcher is finished. He won’t get another chance.”21 But the Expos wasted no time putting Alcala into action before that. On May 24 he pitched a perfect 13th inning at Wrigley Field and picked up his first save of the season as Montreal defeated the Chicago Cubs, 5-4. Williams had high hopes for the tall Dominican. “Alcala was 11-4 with the Reds last year, even though he didn’t start regularly,” he said, “They say he’s a little wild, but maybe that’s because he didn’t pitch on a regular basis. Our reports are that he is a strong thrower with a good slider and sinker. We will give him the chance to pitch every four days, with another day’s rest every now and then.”22

True to his word, Williams inserted Alcala into his starting rotation on May 27. In the third inning that night in St. Louis, Alcala hit the only home run of his major-league career. But he was knocked out of the box in the fourth frame and took the loss as the Expos went down, 7-3. For several weeks Alcala remained in the rotation, with indifferent success. In late July Williams demoted him to the bullpen. Control remained Alcala’s bugbear: he walked 47 in 101⅔ innings with Montreal.

The game on July 2, 1977, at Montreal’s Stade Olympique, made a bit of baseball history: it was the first time that Dominican starting pitchers faced each other in the majors. Alcala never did face off against old friend Joaquin Andujar, who was traded to Houston after the 1975 season. His opponent that night was Nino Espinosa of the Mets. Santo went six innings and got the win, his last in the majors. Alcala’s last big-league appearance came at home on September 25, 1977. He relieved Jackie Brown in the seventh inning, with Montreal trailing the Phillies, 7-5. Garry Maddox flied out to right field, but after Bob Boone singled, Jay Johnstone flied to center and Terry Harmon popped up to first base. No one knew it at the time, but at 24—the age at which many big-league careers are just getting started—Santo Alcala’s was over. His major league totals were 14 wins, 11 losses, and an ERA of 4.76. Not very impressive numbers, but that 11-4 mark for the Big Red Machine in 1976 will forever be a bright spot in the record books.

Alcala joined a new winter-ball team for the 1977-78 season: Águilas Cibaeñas. Águilas won the Dominican title that year—the only time Alcala was a member of a champion team in his homeland. However, he pitched in only two games that winter and did not appear in the league playoffs.

In spring training 1978, Dick Williams still envisioned Alcala as a part of Montreal’s starting rotation. “The fifth starting spot remains open,” he said. “The fifth starter role will also call for long relief before we hit the stage where we need five starters. The chief contenders are Fred Holdsworth and Santo Alcala. It will all depend on what they show us this spring. They will make the decision for us.”23

On March 23, 1978, the Seattle Mariners selected Alcala off waivers from the Expos for $20,000. He reported to Seattle with a sore arm, then caught a case of the flu. The Mariners tried to annul the deal, but baseball commissioner Bowie Kuhn ruled against them. On April 3, without ever having pitched a game for the Mariners, Alcala was placed on the 21-day disabled list with a strained right shoulder. When he recovered, the Mariners assigned him to the San José Missions of the Class AAA Pacific Coast League. Initially, he refused to report to San José. “They have not let me pitch,” he said. “So how do they know what I can do? I want my release.” Alcala may have had a point, but he relented and reported to San José. In his first game for the Missions, on May 7, he pitched a five-hitter to beat Albuquerque, 4-3. Battling injuries, he pitched in only 15 games for that season, for a record of 5-2. At the end of the season Seattle returned the injured right-hander to the Expos, who reportedly agreed to replace him.24

Alcala did not play at home at all in the 1978-79 season. Montreal placed him on the roster of its Triple-A club in Denver in 1979. As of early April, though, he had reportedly joined the new Inter-American League. There is no record of his ever playing in that league. According to a report in the Cincinnati Enquirer on June 26, when the short-lived IAL was on the verge of folding, Alcala had been pitching batting practice for the Santo Domingo team, the Azucareros.25 That same report said that Andujar had gotten Alcala a tryout with the Astros. That didn’t pan out, but Alcala did play in seven games in 1979 for the Buffalo Bisons, Pittsburgh’s affiliate in the Class AA Eastern League. How the Pirates obtained him is not reported.

In 1980 Alcala pitched in nine games for the Portland Beavers, Pittsburgh’s club in the Pacific Coast League. He also got into 15 games, all starts, with Chihuahua in the Triple-A Mexican League. He pitched well for the Dorados, with 11 complete games and an ERA of just 1.99 in 113 innings pitched. However, his won-lost record was just 5-9. Alcala returned to Portland in 1981 and spent the entire season there, going 7-13 with a 4.39 ERA. During the winter of 1981-82, he wrapped up his winter-ball career with seven last appearances for Águilas Cibaeñas. In his 10 seasons at home, Alcala posted a record of 17-29 in 142 games, with a 3.95 ERA.

In February 1982, the Pirates organization optioned Alcala’s contract to the Monterrey Sultanes in the Mexican League. He made a spectacular debut there on April 3, striking out 15 Nuevo Laredo batters in seven innings.26 Again he pitched well overall, with 12 complete games in 26 starts and a 2.92 ERA in 194 innings pitched. Yet again his record of 9-15 did not reflect it. Alcala remained in the Mexican League, dividing the 1983 season between the Saltillo Saraperos and the Aguascalientes Rieleros. Oddly enough, even though his ERA rose to 3.72 that season, he posted a record of 10-4 in 22 games. He played for the Toluca Truchas in 1984, but after five ineffective appearances there, his Mexican career was over. Indeed, so was his career in Organized Baseball, at the age of 31. (Alcala wasn’t quite through playing ball, though. In 1989, when the Senior Professional Baseball Association came into being, he pitched for the Gold Coast Suns. He also helped get Joaquin Andujar to join the Suns.)27

Alcala returned to live in San Pedro de Macoris, where a street—Calle Santos Alcalá—is named after him. He fathered five children from three different relationships: José Alcalá Castro, Sandra Alcalá Mejía, Santos Alcalá Mejía (“Santico,” who was born in Montreal), Yosairy Alcalá Mejía (now deceased), and Johanna Alcalá Encarnación.

Beyond that, however, American media reported next to nothing about Alcala’s life in nearly 30 years. They cannot ignore what he did for the Reds in 1976; indeed, the Cincinnati Enquirer caught up with him during the team reunion of 2008. Otherwise, “I wouldn’t be standing here right now,” he said.28 However, U.S. writers have shown slight interest in Santo Alcala’s contemporary life. It’s ironic, because his wife Yolanda says, “The U.S. has been our second home and has given us and our children permanent hospitality. We have great gratitude toward America.”29

His homeland still appreciates his contributions to the game, though. For example, in 2007 another pitcher from San Pedro de Macoris, Daniel Cabrera, cited Alcala’s help. Cabrera had major control problems, and he said that his height (6-feet-7) was a big reason—as it had been for Alcala.30

Alcala has been a pitching coach in various organizations, including the Chicago White Sox, the Seattle Mariners, and the Los Angeles Angels. He crossed the Pacific in 1997 to join the China Times Eagles in Taiwan. He has been coaching in the Dominican Republic with the Angels chain since 1998, and on occasion his name has surfaced in reports from publications such as Baseball America. He has also coached a few seasons in the Dominican league with Estrellas Orientales. He continually gives back to his school, Liceo José Joaquín Pérez, by coaching teenagers in baseball during the morning hours.31

When Joaquin Andujar died in September 2015, Alcala was in the news again because he attended the funeral in San Pedro de Macoris. He recalled that Andujar often said to him, “Between us two, you’re the prospect. I’m the one just looking for a chance.”32 Yet even though Santo Alcala’s promise as a pitcher was largely unrealized, he remains a happy man. As his wife said, “Santo is not perfect—he is a human being—but he is a very special individual who has led a peaceful and exemplary life.”33

In June 2016, 40 years after his 11-win season in the majors, Alcala returned to Cincinnati for another reunion of the Big Red Machine as Pete Rose was inducted into the Reds Hall of Fame. His wife Yolanda said, “We belong to a family with Pete Rose and all the Reds. Everyone is so excited for this blessing.”34

Last revised: June 26, 2016

Acknowledgments

Grateful acknowledgment to Santico Alcala and Yolanda Mejía for their assistance with this story. Thanks also to Malcolm Allen for additional input and the introduction to Santico, who in turn introduced Yolanda.

Other sources

http://history.winterballdata.com (Dominican statistics)

All e-mail cited is in author’s possession.

Notes

1 “Shortstops Grow in San Pedro,” Chicago Tribune, July 21, 1989.

2 Ian MacDonald, “[Gary] Carter, [Gerry] Hannahs fume as Expos wheel and deal,” Montreal Gazette, May 24, 1977, 13.

3 E-mail from Yolanda Mejía to Rory Costello, April 12, 2016 (hereafter “Mejía e-mail”).

4 Ibid.

5 Dave Nightingale, “Baseball’s Secret Treasure,” The Sporting News, August 19, 1985, 24.

6 “Shortstops Grow in San Pedro.”

7 Mejía e-mail

8 Santo Alcala file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York.

9 Cuqui Córdova, “Santos Alcalá – El Escucha Cubano Wilfredo Calviño Lo Firmó para el Cincinnati (1969),” Listín Diario (Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic), unknown date. Printout from Malcolm Allen’s files of online story that is no longer available.

10 At the present time every one of the 30 major league ball clubs sponsors an academy in the Dominican Republic, including five in San Pedro de Macoris, operated by Atlanta, Detroit, Milwaukee, the Angels, and Toronto. Most of the academies are operated as boarding schools, offering instruction in the English language, honing the skills of the young players, and signing the most promising to professional contracts.

11 John Erardi, “Latin pipeline helped fuel ‘70s powerhouse,” Cincinnati Enquirer, November 15, 2008, accessed April 18, 2016, http://www.redszone.com/forums/archive/index.php/t-72541.html. Córdova, “Santos Alcalá.” Calviño (1927-2008) was a native of Cuba. He was a minor-league catcher from 1947-53 and later became a manager in Nicaragua, Mexico, and Venezuela. He scouted for several other major-league organizations besides the Reds.

12 Earl Lawson, “Alcala, Zachry Plug Hole in Reds’ Hill Staff,” The Sporting News, June 12, 1976, 11.

13 Duke DeLuca, “Iorg to Kreke: ‘Don’t Worry, Buddy,’” Reading Eagle, June 28, 1973, 42.

14 Earl Lawson, “Reds Forecast Half-Million Advanced Ticket Sales,” The Sporting News, December 15, 1973, 33.

15 “Alcala Hears Call,” The Sporting News, September 20, 1975, 32.

16 Earl Lawson, “Darcy, Carroll Grow Edgy Checking Reds’ Timetable,” The Sporting News, March 20, 1976. 30.

17 “Speed Fails, So Reds Beat Dodgers with Youth,” Associated Press, May 31, 1976.

18 E-mail, Malcolm Allen to Rory Costello, April 11, 2016.

19 Lawson, “Alcala, Zachry Plug Hole in Reds’ Hill Staff”

20 Earl Lawson,“Slumping Reds Test Hume as No. 5 Starter,” The Sporting News, June 11, 1977, 8; Alcala quoted in Bob Herzel, “Reds Trade Alcala to Expos,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 22, 1977.

21 MacDonald, “Carter, Hannahs fume as Expos wheel and deal”

22 Ian MacDonald, “Alcala, Bahnsen Bolster Expo Hurling,” The Sporting News, June 11, 1977, 28.

23“Four Expo Starting Jobs Already Locked Up,” The Sporting News, March 4, 1978, 23.

24 Hy Zimmerman, “M’s Sore Arms and Flu,” The Sporting News, April 15, 1978, 33; “M’s Abbott Starting Fast in His Bid for 20 Victories,” The Sporting News, April 22, 1978, 23; “Reynolds Lonesome Mariners Hitter,” The Sporting News, May 20, 1978, 18; “M’s Banking on Draft Choice for Paciorek,” The Sporting News, November 25, 1978, 46.

25 “New league makes debut this week,” Associated Press, April 10, 1979; “Reds Note,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 26, 1979.

26 “Friday’s Sports Transactions”, United Press International, February 5, 1982; Salo Otero, “Mexican League Hurlers in Top Form,” The Sporting News, April 24, 1982, 36.

27 Ed Giuliotti, “Andujar Can Still Pitch, and Has Tamed His Temper,” Palm Beach Sun-Sentinel, January 28, 1990.

28 Erardi, “Latin pipeline helped fuel ‘70s powerhouse”

29 Mejía e-mail

30 Enrique Rojas, “Mejorar control es prioridad en carrera de Daniel Cabrera,” Hoy (Santo Domingo, Dominican Rupublic), February 21, 2007.

31 Mejía e-mail

32 Pedro G. Briceño, “SPM despide a uno de sus grandes héroes deportivos,” Listín Diario, September 9, 2015.

Full Name

Santo Anibal Alcalá

Born

December 23, 1952 at San Pedro de Macoris, San Pedro de Macoris (D.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.