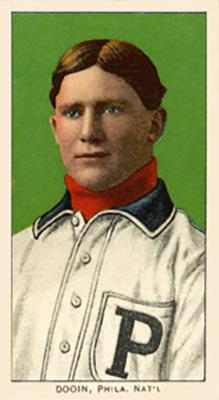

Red Dooin

Despite his diminutive size, Charley “Red” Dooin was an outstanding defensive backstop who caught 1,124 games for the Phillies, a team record until Mike Lieberthal topped it in 2006. “This writer has watched catchers from the days of Charley Farrell and Connie Mack and none could go farther for fouls or block off a runner at the plate as Dooin did,” wrote one reporter in The Sporting News in 1925. “When Dooin was in his playing prime he never weighed more than 145 lbs., yet he was absolutely spike fearless and would block the swiftest and heaviest runner when there was only a small chance to retire him.”

Despite his diminutive size, Charley “Red” Dooin was an outstanding defensive backstop who caught 1,124 games for the Phillies, a team record until Mike Lieberthal topped it in 2006. “This writer has watched catchers from the days of Charley Farrell and Connie Mack and none could go farther for fouls or block off a runner at the plate as Dooin did,” wrote one reporter in The Sporting News in 1925. “When Dooin was in his playing prime he never weighed more than 145 lbs., yet he was absolutely spike fearless and would block the swiftest and heaviest runner when there was only a small chance to retire him.”

Born in Cincinnati on June 12, 1879, Charles Sebastian Dooin was working as a cloth cutter and clothing salesman at age 18, but despite standing only 5’6″ and weighing less than 120 lbs., he aspired to be a catcher. In 1898 he persuaded Indianapolis of the Western League to give him a break-and wound up with a broken hand in his first game. The next year he signed with Rock Island of the Western Association. This time the league, not Dooin, broke up. He hooked on with St. Paul and hit a game-winning triple in his debut, after which manager Charles Comiskey asked him if he had a trade. “I’m a tailor,” Red said. The future Chicago White Sox magnate advised him to go back to tailoring. Undaunted, Dooin landed with his third team of the 1899 season, Youngstown of the Interstate League. He sassed the manager and was gone in a week.

Still undaunted, Red went home to Cincinnati and joined a semipro team called “Spinney’s Specials,” playing through 1900 alongside another mighty mite named Miller Huggins. In 1901 St. Joe of the Western League needed a catcher and sent Dooin a contract. When he reported, the manager took one look at him and said, “I wanted a catcher, not a jockey.” But Red lasted the season, catching and playing first base and the outfield, batting .252.

Dooin finally caught a good break in 1902. The new American League’s raids on NL rosters created plenty of openings, and the Phillies picked up the tiny 22-year-old backstop. He still weighed less than 150 lbs., but he was tough, scrappy, and fearless. Like the legs of many catchers of the time, Dooin’s were hashed by flying spikes. One of his claims to fame remains unrecognized. By Dooin’s account, one day in 1906 the Penn athletic director, Mike Murphy, took one look at his scarred legs and suggested that Red wear shin guards. “You can’t play baseball with shin guards,” Dooin said. “They play football with them,” said Murphy, “and they run just as fast as you.” The next day Murphy brought him a pair of rattan guards. Dooin put them on under his stockings. The first time a sliding runner bounced off them, Red was sold. He had some lighter ones made from papier-mâché and continued to use them under his stockings.

Baseball history credits Roger Bresnahan with introducing shin guards. Dooin always maintained that Bresnahan got the idea from him a year later. “We were playing the Giants in Philadelphia, and I blocked the Rajah as he came flying into the plate. In the collision he went down and came in contact with my legs. ‘Say, what have you got under your stockings?’ the astonished Bresnahan asked. In the clubhouse after the game I showed the guards to Roger. Afterwards he went down to a Philadelphia sporting goods house, where I had mine made, and purchased a pair for himself. But because of his bulk and the fact that any additional weight would slow him up if he wore the guards like I did, Bresnahan had to put aside the idea of leg protection. He continued to experiment, however, and the white cricket shinguards resulted. He only wore them behind the plate. He took them off when going to bat. I continued to wear mine under the stockings.”

In 1910 Horace Fogel, backed by Cincinnati-based Taft money, bought the Phillies. A promotion-minded baseball writer, Fogel wanted a feisty, colorful manager. Red Dooin was all of that. The temperamental redhead took over the helm as player-manager, but a broken ankle during the 1910 season and a broken leg in 1911 ended his days as a regular player. The latter injury occurred during a game in St. Louis in which Dooin had blocked off three Cardinals at the plate in the early innings. Each time the runner probably should have scored, and St. Louis manager Roger Bresnahan threatened to fine the next player who was blocked by Dooin. Later in that game, St. Louis outfielder Rebel Oakes, remembering Bresnahan’s threat, charged the plate on a close play with one leg describing a scissors-like motion. The collision broke one of Dooin’s legs, shin guards and all.

For five years the Phillies played in the shadow of Connie Mack‘s mighty Athletics machine, but nearly every season Dooin had them challenging the NL powers of Chicago and New York before fading from the race. William F. Baker—he of the shallow pockets—replaced Fogel as club president in 1914, the year the Federal League cut out the heart of the Phillies. At the same time, it also almost ruined the minor league Baltimore Orioles—a near break for Dooin. When Mack turned down Baltimore’s offer of Babe Ruth and Ernie Shore, Jack Dunn offered them, with shortstop Claud Derrick, to Red Dooin and the Phillies for $19,000. According to Dooin, “Baker nearly exploded when I reported to him that Dunn asked $19,000 for three of the most promising players in the International League. He told me he wouldn’t give $19,000 for the whole International League.”

It’s fun to imagine how many home runs the Babe might have hit in Baker Bowl—if Baker somehow managed to hold on to him—but alas, the Ruth-less Phillies finished sixth in 1914, after which Dooin was fired. The Phillies had compiled a respectable 392-370 record over the course of his five-year tenure, but the following year they went on to win their only pennant of the Deadball Era. Red started the 1915 season back in Cincinnati, then went to the Giants, for whom he caught and coached through 1917. He played for Rochester in 1918 and caught his last game at age 40 while managing Reading of the International League in 1919.

Dooin retired to Atlantic City, where he owned several properties and had substantial money in the bank, but in 1932 the banks closed and he lost all his cash, forcing him to sell off some of his real estate. Dooin had a rich baritone voice—during his playing days he had performed on the winter vaudeville circuit as a singer and actor in addition to his work as assistant manager of the men’s department of a Philadelphia department store—so he went back to singing, in vaudeville and on the radio. Red and his wife, Julia, moved to Rochester, New York, where he died at age 71 on May 14, 1952. Married almost 50 years, they had no children.

Note: A different version of this biography appeared in Tom Simon, ed., Deadball Stars of the National League (Washington, D.C.: Brassey’s, Inc., 2004).

Sources

Much of the material came from a lengthier piece the author did on Dooin for Phillies Report, published probably in 1989 (issue date unknown), which was based on contemporary and later interviews with Dooin.

Full Name

Charles Sebastian Dooin

Born

June 12, 1879 at Cincinnati, OH (USA)

Died

May 14, 1952 at Rochester, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.