Roger Bresnahan

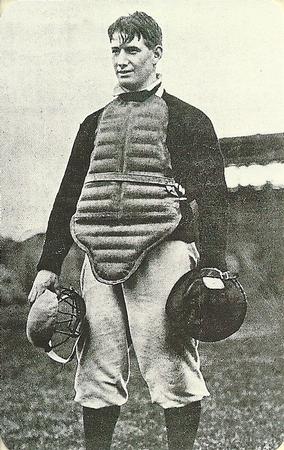

A versatile athlete who played all nine positions at the major-league level, Roger Bresnahan is generally regarded today as the Deadball Era’s most famous catcher, as well known for his innovations in protective equipment as for his unusual skill package that made him one of the first catchers ever used continuously at the top of the batting order. Catchers almost always batted eighth in the Deadball Era, but Bresnahan was adept at reaching base (he had a .419 on-base percentage in 1906) and possessed surprising speed despite his 5’9″, 200-pound frame. Like his close friend and mentor, John McGraw, the .279 lifetime hitter had a quick temper and was inherently tactless. One reporter described him as “highly strung and almost abnormally emotional,” but he also had a soft heart. During his five years as a big-league manager, Bresnahan reportedly fined more players and took less money than any of his peers.

A versatile athlete who played all nine positions at the major-league level, Roger Bresnahan is generally regarded today as the Deadball Era’s most famous catcher, as well known for his innovations in protective equipment as for his unusual skill package that made him one of the first catchers ever used continuously at the top of the batting order. Catchers almost always batted eighth in the Deadball Era, but Bresnahan was adept at reaching base (he had a .419 on-base percentage in 1906) and possessed surprising speed despite his 5’9″, 200-pound frame. Like his close friend and mentor, John McGraw, the .279 lifetime hitter had a quick temper and was inherently tactless. One reporter described him as “highly strung and almost abnormally emotional,” but he also had a soft heart. During his five years as a big-league manager, Bresnahan reportedly fined more players and took less money than any of his peers.

The seventh child of Michael and Mary (O’Donohue) Bresnahan, Roger Phillip Bresnahan was born on June 11, 1879, in Toledo, Ohio. Early in his baseball career he acquired the title “Duke of Tralee” due to a frequently repeated inaccuracy that his birthplace was Tralee, Ireland; in truth his parents had immigrated to the United States from Ireland in 1870. Roger developed his enthusiasm for baseball while attending Catholic grade school in Toledo. In 1895 the stocky 16-year-old got his first paying baseball job with a semipro team from Manistee, Michigan. The following year, after graduating from Toledo’s Central High School, Roger became a full-fledged professional with Lima of the Ohio State League, playing mostly catcher but also occasionally pitching.

Bresnahan pitched a six-hit shutout against the St. Louis Browns in his major-league debut with the Washington Nationals on August 27, 1897. He went on to bat .375 and win all four of his 1897 pitching decisions, but the following spring Washington released the 18-year-old rookie when he held out for a higher salary. After splitting the 1898 season between Toledo of the Inter-State League and Minneapolis of the Western League, Bresnahan returned to the National League in 1900 and appeared in two games for Chicago. Joining the Baltimore Orioles of the fledgling American League in 1901, he served as John McGraw’s utility man for the next season and a half, playing a significant number of games at catcher, third base, and the outfield. When McGraw and several Oriole teammates jumped to the NL’s New York Giants in midseason 1902, Bresnahan went with them.

Roger Bresnahan spent the next six seasons in New York and became one of baseball’s biggest stars. In 1903 he was the Giants’ regular center fielder, establishing career highs with a .350 batting average (only five points behind league-leader Honus Wagner), a .443 on-base percentage (second in the NL behind Roy Thomas‘s .453), and 34 stolen bases. Though he continued to play the outfield on occasion, Bresnahan became New York’s first-string catcher in 1905, forming half of the acclaimed battery of Mathewson and Bresnahan, one of the greatest pitcher-catcher combinations in baseball history. In that year’s World Series, Bresnahan caught and batted leadoff in all five games; his .313 batting average was the highest among all Series participants.

It was during his years with the Giants that Bresnahan made his contributions to the development of playing equipment. After a hospital stay necessitated by a beaning, he experimented in 1905 with the Reach Pneumatic Head Protector, which was essentially a leather football helmet sliced in half to protect the left side of a right-handed hitter’s head. More influential were his efforts with shin guards. After discovering in a home-plate collision that Red Dooin of the Phillies wore papier-mâché protectors under his stockings, Bresnahan showed up on Opening Day 1907 wearing a huge pair of shin guards modeled after a cricketer’s leg pads. At first Roger’s innovation met with ridicule and protest—Pirates manager Fred Clarke insisted the guards posed a danger to sliding runners—but by 1909 a less bulky version was in general use. In another innovation that remains in use to this day, Roger added leather-bound rolls of padding to the circumference of his wire catcher’s mask around 1908 to help absorb the shock of foul tips.

At the end of the 1908 season, in which Bresnahan caught a career-high 139 games, St. Louis owner Stanley Robison expressed interest in obtaining Roger to serve as player-manager of the Cardinals. McGraw didn’t want to stand in the way of his 29-year-old protege-as long as the Giants benefited in the process. On December 12, 1908, New York traded Bresnahan to St. Louis for the Cardinals’ best pitcher, Bugs Raymond, their best hitter, Red Murray, and catcher Admiral Schlei, whom the Cards had obtained from Cincinnati (at the Giants’ insistence) for promising pitchers Art Fromme and Ed Karger. Appearing in just 72 games as a player, his fewest since establishing himself as a major leaguer in 1901, Roger batted a disappointing .244, and the Cardinals finished seventh, a slight improvement over their last-place finishes of the two prior years. The Cards finished seventh again in 1910 when Bresnahan bounced back to hit .278 in 88 games.

In 1911 Robison died and control of the team passed to his niece, Helene Robison Britton. In one of her first interviews after claiming her inheritance, Britton told a reporter that she viewed Bresnahan as a good manager. “I like his system,” she said. “Indeed, I adore it, even if it has not been climbing toward the first division.” Shortly thereafter she told another reporter that “my great aim will be not to interfere with, but rather to further the system Mr. Bresnahan already has in effect.” That first year under Britton’s ownership, Roger had the Cardinals in contention for most of the season before they faded to a fifth-place finish. Pleased with the club’s resurgence, Britton rewarded him with a new five-year contract worth $10,000 a year and 10 percent of the club’s profits.

When the Cardinals slipped back to sixth in 1912, however, trouble erupted between the fiery Irishman and his firmly independent boss. According to contemporary reports, the two argued frequently. A story in The Sporting News stated that Bresnahan wanted to buy the club from her, and he continued to press the issue time and again even after she turned him down flat. The final confrontation occurred after a loss to the Cubs, when Helene criticized Roger’s decision on a certain play. According to one report, “he pulled his derby down over his ears and stomped out, declaring: ‘No woman can tell me how to play a ball game!’” At the end of the season, amidst rumors that Bresnahan had not fielded his strongest lineup in a key game against the Giants to help McGraw win another pennant, Britton fired him as manager and sold him to Chicago.

Financially, it turned out to be the best thing that ever happened to Roger. After some legal wrangling, the National League declared him a free agent, and he received a $25,000 signing bonus from the Cubs. Eventually he settled a lawsuit against Britton for another $20,000. Serving as Jimmy Archer‘s backup in 1913, Bresnahan continued gathering a healthy salary even though his playing abilities had slipped. In 1915 the Cubs named him player-manager, but that year he batted a career-low .204 and was released after the Cubs fell below .500 for the first time since 1902.

With the savings he had amassed over the years, Bresnahan purchased the former Toledo Mud Hens, which had been transferred to Cleveland in 1914 (and renamed the Spiders) to prevent the renegade Federal League from taking over League Park, and brought them back to his hometown. Serving as owner and player-manager of the American Association club, Roger provided the last baseball jobs for many of his former teammates on the downside of their playing careers. He played sparingly, finally hanging up his catcher’s gear for good after the 1918 season (though at age 42 in 1921 he was pressed into emergency duty for five games and batted .417 with two stolen bases).

The Mud Hens proved a poor investment, and Bresnahan sold the team before the 1924 season. He then secured a job through his old friend McGraw as a New York Giants coach from 1925 through 1928. Reportedly a millionaire at one time (almost certainly an exaggeration), Roger was hit hard by the stock market crash of 1929. After a coaching stint with the Detroit Tigers in 1930-31, he went to work as a guard at the Toledo Workhouse. As times worsened, the former minor-league magnate performed manual labor for the forerunner of the WPA. Eventually Roger acquired a job as city salesman for Toledo’s Buckeye Brewing Company, working in that position for his remaining years. Early in 1944 he entered politics as the Democratic candidate for county commissioner. The old ballplayer lost the election by a few hundred votes.

At age 65 Bresnahan suffered a heart attack and died at his Toledo home on December 4, 1944. He never achieved one of his greatest ambitions—to give Toledo an American Association pennant—but the city mourned the passing of a man whose heart always lay in his hometown. Survived by his wife, Gertrude, and sister, Margaret Henige, Bresnahan was laid to rest in Toledo’s Calvary Cemetery. The following year he was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

An earlier version of this biography appeared in SABR’s “Deadball Stars of the National League” (Brassey’s Inc., 2004), edited by Tom Simon.

Sources

Dewey, Donald, and Nicholas Accocella. The Biographical History of Baseball. New York: Carroll & Graf, 1995.

News Bee, Mirrors of Toledo No. 24, January 15, 1922.

The Sporting News, December 7, 1944.

The St. Louis Post-Dispatch, December 5, 1944.

Toledo and Lucas County, Ohio, The S. J. Clarke Publishing Co., Chicago and Toledo, 1923.

Toledo Blade, June 11, 1929.

Toledo Blade, May 5, 1944.

Toledo Times, December 5, 1944.

Weber, Ralph Lin. The Toledo Baseball Guide of the Mud Hens, 1893-1943.

Full Name

Roger Philip Bresnahan

Born

June 11, 1879 at Toledo, OH (USA)

Died

December 4, 1944 at Toledo, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.