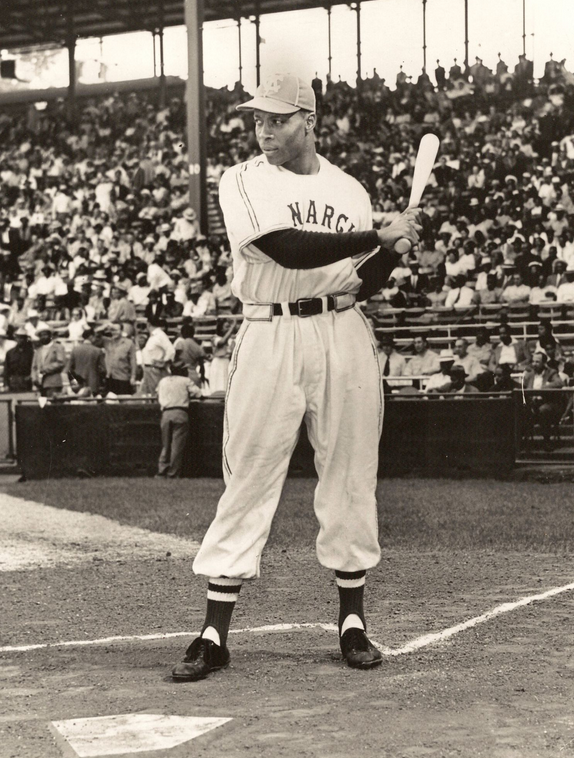

Bob Thurman

Power-hitting Bob Thurman was nicknamed “Big Swish” because the free-swinging power-hitter rarely got cheated at the plate. But Thurman, who was a star pitcher as well as a long-ball-hitting outfielder in the Puerto Rican winter league, also earned a nickname for his hurling. He was dubbed “El Múcaro” or “The Owl” because he always seemed to win the night games that he pitched.

Power-hitting Bob Thurman was nicknamed “Big Swish” because the free-swinging power-hitter rarely got cheated at the plate. But Thurman, who was a star pitcher as well as a long-ball-hitting outfielder in the Puerto Rican winter league, also earned a nickname for his hurling. He was dubbed “El Múcaro” or “The Owl” because he always seemed to win the night games that he pitched.

Thurman, who originally signed with the New York Yankees and then spent several years as the property of the Chicago Cubs, was a month shy of his 38th birthday when he made his major-league debut with the Cincinnati Reds on April 14, 1955. His obstacle-strewn path to the big leagues was long and winding with many detours along the way. But when he finally got an opportunity, the former Negro League star developed into one of the most respected pinch-hitters in baseball and established an all-time National League home run record.

Described as broad-shouldered and muscular, Thurman was a left-handed pull hitter who was said to be extremely fast on the bases for a big man. Often referred to as “Big Bob,” he’s listed as being 6’1″ tall and weighing 205 pounds in The Baseball Encyclopedia, but during his Negro League career he was reported to be a 6’4″, 230-pound giant. His actual size was probably somewhere between the two.

From 1955 until he was released in early 1959, Thurman was one of the most popular players on the Cincinnati Reds. The Reds were an outfit that had been slow to integrate, but made tremendous strides in a short time thanks to the examples set by respected veteran black players like Thurman. Off the field Thurman served as an informal traveling secretary for the Reds’ contingent of black players, taking responsibility for arranging accommodations on the road when they couldn’t stay with the team and assisting younger players in getting acclimated to the major leagues.

Robert Burns Thurman grew up in Wichita, Kansas. Most sources indicate he was born in Wichita, although nearby Kellyville, Oklahoma is listed as his birthplace in the Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues.

Bob was born May 14, 1917, but he trimmed a few years off his age before entering organized baseball. In The Sporting News coverage of Thurman’s acquisition by the Yankees in 1949, he was reported to be 26 years old. Apparently most of the baseball world bought off on this little fabrication because Thurman’s birthday was listed as 5/14/23 by the Doubleday Official Baseball Encyclopedia, Annual Baseball Register, Baseball Digest and even the backs of his baseball cards during his active career.

Somewhere along the line, however, Thurman must have slipped up because the Macmillan Baseball Encyclopedia reported his birth date as 5/14/21 and a 1957 Associated Press article mentioned that he was 34 years old in 1955 when he broke in with the Reds. Many years after his retirement Thurman confessed to his real age in a neatly hand-written 1982 letter to the Baseball Hall of Fame as follows:

“Many Baseball clubs like to put players ages back a few years. Mine was put back several times, so much so, that I always use the baseball age. Even when I joined the pension, I didn’t think of [using] my correct age. So my real [birth date] is May 14, 1917.”

Thurman started his baseball career playing semipro ball with various teams in the Wichita area before entering the U.S. Army at the beginning of World War II. He was stationed in New Guinea and Luzon and saw combat action in the Pacific Theater of Operations. His baseball talent became evident while playing military ball in the Philippines, and when he was discharged in 1945 an offer to play for the Homestead Grays in the Negro National League was waiting for him.

In 1946, Thurman’s first season with the Homestead Grays, their roster included some of the greatest names in Negro baseball history. Catcher Josh Gibson, first baseman Buck Leonard, outfielder Cool Papa Bell, infielder Sam Bankhead, pitcher Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe, outfielder Vic Harris, and third baseman Howard Easterling were some of the veteran stars. In addition, future major leaguers Sam Jones, Dave Hoskins, Luis Marquez, and Dave Pope were also with the Grays. Thurman’s mound work was mediocre, but he got some playing time in the outfield and hit .408 with power.

The next year Cool Papa Bell retired and big Bob found himself playing the outfield more than pitching. He handled right field with new recruit Luke Easter in left and league batting champ Luis Marquez in center field. Thurman hit .338 for the 1947 season and showed good power with six homers in 157 at-bats. In 1948 he hit .345 and also posted a 6-4 won/lost record as a regular starting pitcher to help the Grays capture the last Negro National League pennant. They also defeated the Birmingham Black Barons in the World Series that year before their powerhouse squad was dismantled along with the once grand league.

Like most Negro Leaguers, Thurman had to play winter ball to make ends meet. He began playing with the Santurce Crabbers in the Puerto Rican winter league and became a big fan favorite. He led the league with nine homers in the winter of 1947-48 and doubled that total the next winter before reporting to his new employers the Kansas City Monarchs, another fabled Negro League franchise in the newly reorganized Negro American League.

The Monarchs, managed by Buck O’Neill, were still a powerhouse. Listed on their roster were long-time Negro League stars Willard Brown, Booker McDaniels, Nat Peeples, Bonnie Serrell, and Theolic Smith, as well as future big leaguers Elston Howard, Gene Baker, Connie Johnson, Frank Barnes, and Curt Roberts. But with the integration of organized baseball, the Negro Leagues were in their death-throes. The only way they could survive was by selling off their star performers and Thurman’s big season in Puerto Rico had attracted the attention of the major leagues.

In his preview of the 1949 East-West All-Star Game clash, Wendell Smith of the Pittsburgh Courier wrote, “Another player who seems destined to move up… is Bob Thurman. He is also with Kansas City and many tab him as Josh Gibson’s successor when it comes to hitting. Bob is hitting .327 and is a home-run hitter deluxe… Thurman’s tootsies are lined with mercury. He’s leading both leagues in stolen bases with 12. Formerly a pitcher, he can throw with the best of ’em and is definitely ticketed for the majors.”

But Thurman would never play in the East-West classic. On July 29, 1949 it was announced that his contract, along with catcher Earl Taborn’s, had been purchased from the Monarchs by the New York Yankees.

Thurman was one of the first black players signed by the Yankees. He was assigned to the Newark Bears of the International League and slammed three homers in his first week in organized baseball, including one tape-measure blast that was said to be the longest hit in the old Newark park in 30 years. In 59 games for the Bears he hit .317 before a hand injury sent him to the sidelines.

But despite his promising freshman campaign, the Yankees disposed of him, transferring his contract to the Chicago Cubs. Thurman spent the 1950 season with Springfield in the International League where his batting average fell to .269 with only 12 homers. He spent the next two years with the San Francisco Seals club of the Pacific Coast League. He hit .274 and .280, respectively, but failed to display the power expected of him. As far as the Cubs were concerned, however, it probably didn’t matter how many homers Thurman smashed since they still weren’t ready to integrate at the major-league level. During the winter following the 1952 season, Thurman’s contract was sold to Charleston of the American Association. But Thurman didn’t play for Charleston or any other team in organized baseball for the next two years.

Thurman had continued to play for Santurce in the Puerto Rican winter league after entering organized ball and was one of the biggest names in Latin American baseball. In the early 1950s, the Dominican Republic was in the process of establishing a professional league called the Dominican Summer League. The new league was not affiliated with organized baseball and was able to lure several minor leaguers with generous salary offers. Since Thurman was nearing 36 years of age and going nowhere in the Cubs system, he was receptive to abandoning organized baseball for a more lucrative offer from the Escogido team. He spent two years in the Dominican league, leading the loop in homers and RBIs in 1954 and even pitching occasionally.

When he opted to play in the Dominican Republic, Thurman was suspended from organized baseball. Therefore, when the Caribbean circuit slid under the umbrella of organized baseball in 1955, he was in limbo. Technically he was still under contract to the Cubs, although they didn’t really seem to want him. But he proceeded to create a market for his services with his play in the 1954-55 Puerto Rican winter league. He hit .323 and slammed 14 homers for a Santurce team that revered veteran baseball man Don Zimmer, who had been in the game for more than 50 years as a player, manager, and coach, called “the best winter league baseball club ever assembled.”

Zimmer, who at the time was the jewel of the Brooklyn system, was the club’s shortstop while Thurman played right field and hit 323. Reigning National League Most Valuable Player, Willie Mays, played center field and led the winter league in batting, and young Roberto Clemente, who would join the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1955, hit .344 for fourth place in the league rankings. George Crowe, who’d led the American Association in homers and RBIs and would be a regular for the Milwaukee Braves in 1955, played first base and former Negro League star Bus Clarkson, who topped the Texas with 42 homers in 1954, handled third. Harry Chiti, who would be the Cubs regular catcher the next year, shared backstop duties with future New York Giants receiver Valmy Thomas, and another future major leaguer, Giants prospect Ron Samford, manned second base. The pitching staff was led by Ruben Gomez, a 17-game-winner for the 1954 World Champion Giants, Sam Jones, who would lead the National League in strikeouts in 1955, and Bill Greason, a Cardinal farmhand and former Negro League standout. And also taking an occasional turn on the mound was 37-year-old left-hander Bob Thurman. Although Thurman was strictly an outfielder in organized baseball, he continued to pitch in the winter leagues. In previous winters he’d been among the top hurlers in the league, but in 1954-55 his services weren’t required quite as often on the mound.

Impressed by his winter-league heroics and unaware of his true age, the Cincinnati Reds purchased the rights to Thurman from the Cubs for a reported sum of $2,000. It would turn out to be a terrific investment. Ironically, Thurman’s big-league debut occurred on the same day that Elston Howard became the first black man to play for Thurman’s original organization, the Yankees. During the 1955 season Thurman shared left field with several other players and hit seven homers in only 152 at-bats, though his batting average was only .217. The next year, however, he raised his batting mark to .295 and slammed eight homers in 139 chances at the plate, helping the powerful Reds to tie the all-time major-league home run record of 221 set by the 1947 New York Giants. On August 18, 1956 he slammed three consecutive homers and double against the Milwaukee Braves, enabling the Reds to tie a major-league record with eight homers in the game.

The next season Thurman celebrated his birthday with a home run against the Philadelphia Phillies on May 14, 1957. Unbeknownst to organized baseball at the time, he was the first player to homer on his 40th birthday; and it didn’t happen again until Joe Morgan did it in 1983. The 1957 campaign would be Thurman’s best season in the major leagues, even though it was interrupted by a trip to the minors. He started the year on fire and was hitting .351 on June 1, but by the end of the month his average had skidded 92 points. On August 2, he was dispatched to Seattle of the Pacific Coast League to make room for Joe Taylor, a younger black outfielder.

Thurman took the demotion in stride. Instead of sulking about it, the irrepressible outfielder told Reds manager Birdie Tebbetts, “I know I’ll be back and when I am I’ll make you play me.”

When Thurman reported to Seattle the next day, after flying all night, the game was already underway. But Seattle manager Lefty O’Doul asked him to suit up right away. “I may need you to hit one,” he cracked. Sure enough, “Big Swish” was needed in the eighth inning and obliged with a pinch homer. He ravaged Pacific Coast League pitching for seven more long ones before being recalled by the Reds later the same month.

The Reds, who missed Thurman’s clubhouse presence as much as his big bat, were in a deep slump and the big guy responded by giving them an immediate lift. After flying in from Seattle overnight, he rejoined the Reds in Philadelphia on August 27 and smashed a three-run ninth-inning homer to give the Reds a desperately-needed 5-2 victory.

After two at-bats off the bench on the 30th, Thurman banged a two-run homer off Milwaukee’s Lew Burdette in his next start on August 31, but the Reds still suffered their 15th loss in 18 outings. The next day, however, he doubled home a run and added a two-run circuit smash as the Reds beat the Cardinals behind Brooks Lawrence. In total, he hit four home runs and drove in a dozen runs in his first five games back to help get the team back on track. The Reds won 18 of 30 games after the big outfielder’s recall to finish the season with 80 victories.

Thurman finished the 1957 campaign with 16 home runs and 40 RBIs in only 190 at-bats for the Reds. At the time, he was the first National Leaguer and only the second player in major league history to slam that many homers in less than 200 at-bats. His home run per at-bat percentage of 8.4% was better than league-leader Duke Snider‘s 7.9%, although Big Bob didn’t have enough plate appearances for official ranking. His eight homers in 104 at-bats with Seattle gave him a personal total of 24 for the year in less than 300 chances at the plate.

Thurman remained with the Reds through the entire 1958 campaign, but hit only .230 with four homers. After a few pinch-hitting appearances early in the 1959 season, he returned to the minor leagues but failed to hit well with either Seattle or Omaha (American Association).

In 1960, the 43-year-old Thurman drifted into the Washington Senators organization and finally reported to Charleston, seven years after the franchise had first tried to acquire his services. He hit .274 with 10 homers for the American Association club. On August 21, Thurman received his first and only opportunity to pitch in organized ball. Charleston starter Jim Kaat had been knocked out of the box and the score was 10-5 when the 43-year-old veteran was summoned from right field to take the mound against Dallas-Fort Worth. Thurman held them scoreless the rest of the way, striking out a trio of batters and giving up a pair of hits in three innings. He also went 3-for-4 at the plate that day. The next year he finally hung up his spikes after 21 games with Charlotte in the South Atlantic League.

Thurman ended his major-league career with a .246 lifetime batting average in 334 major-league games, spread mainly over four seasons. He belted 35 homers and both drove in and scored 106 runs in 663 at-bats. More than one half of his appearances were as a pinch-hitter and he blasted six homers in that role, including four in 1957. In addition, he played 12 winters in the Puerto Rican winter league, 11 with the Santurce Crabbers. He is a member of the Puerto Rican League Hall of Fame and the leagues’ all-time home run leader.

Bob Thurman was never considered one of the best players in major-league baseball, although he might have been if he’d gotten an earlier start. But he easily qualifies as one of the most interesting and unusual stories. Despite the fact that he was 38 years of age when he got his first shot at the majors and was used as a pinch-hitter so often, Thurman’s career totals equate to approximately 30 homers and 90 runs batted in over a full season.

During his career he was regarded as one of the most dangerous clutch hitters in the game. Reds manager Birdie Tebbetts said, “He’s one of the best pinch hitters I have seen in my nearly seventeen years in baseball…..That big boy gets off the bench good and cold, and he just gets hot walking up to the plate.”

Like most hitters, however, Thurman was more productive with the bat when playing full time. His career home run percentage was a respectable 3.4 as a pinch hitter, but an extraordinary 6.0 otherwise. To put Thurman’s 6.0 figure in perspective, Hank Aaron and Willie Mays, the top two National League home run hitters of the 20th century, both finished their fabulous careers with 6.1 home run percentages.

The accomplishments of “Big Swish” are even more amazing when his age is taken into consideration. There are no other hitters who began their big-league careers at a similar age to compare him to. He may have been the oldest slugger to establish a league home run record, even an obscure one, or set the pace in home run percentage as he did in 1957, until Barry Bonds came along.

The fact that the ancient, veteran slugger was playing baseball year-round when he performed his feats makes them even more remarkable. For most of his career, Thurman would leave for the Caribbean immediately after the season ended in the fall and then report for spring training the following year shortly after the Puerto Rican League season closed. More than one baseball talent evaluator wondered how much Thurman’s career in organized ball was harmed by his exhausting schedule.

Then again, there’s the fact that Thurman was a two-way performer, at least during the winter. In Puerto Rico he often gave a pretty fair imitation of a young Babe Ruth. For the 1949-50 season his won-lost mark was 5-3 and he hit .353. In 1951-52 and 1952-53 his records of 6-3 and 5-3 put him among the league pitching leaders. In 1953-54 he had a no-hitter going into the seventh inning of a contest, but had to settle for a two-hit shutout. All the while he was consistently among the league home run leaders and finished sixth in batting in 1954-55 and second in 1955-56.

The likeable, hard-working Thurman joined the Minnesota Twins as a scout after his playing days were over, and his first signee was Rudy May, who would pitch in the majors for 16 years. After about a year and a half he returned to the Cincinnati organization to scout for the Reds. In 1970, he moved closer to his Wichita roots when he became a special assignment scout for the Kansas Royals. Later, when the Major League Scouting Bureau was established, he hooked on with them.

Thurman remained physically active after his playing career, keeping close to his playing weight. He had a gym in his house and was an enthusiastic golfer who, by his own admission, worked off a lot of calories searching the woods for his tee shots. He frequently attended old-timer games and reunions, showing off his youthful-looking physique for his envious old buddies.

When he visited Cooperstown at the age of 74 in 1991, Bob Thurman was still working as a senior partner with Marketing Associates in Wichita. He appeared in excellent shape when interviewed for Sports Collectors Digest by Robert Objoski, who more than a decade later would remember him as one of the nicest players he ever talked to. But the big guy fell victim to Alzheimer’s disease and died on October 31, 1998 in Wichita at the age of 81, leaving behind Dorothy, his wife of 51 years, and their three children.

Bob Thurman put in a lot of hard work and endured some tough breaks to make the major leagues. Like many former Negro Leaguers he was forced to misrepresent his age to get a chance in organized baseball. “If the Reds knew I was that old, they probably would not have signed me,” he said in his 1991 Sports Collectors Digest interview.

But old Cincinnati fans are glad that the Reds didn’t know – for reasons in addition to Thurman’s performance on the field. “Cincinnati wouldn’t have signed Johnny Bench without Bob Thurman,” said long-time baseball executive Herk Robinson, who was in the Cincinnati front office at the time. He was also instrumental in the signing of Wayne Simpson, Hal McRae, and Gary Nolan among others.

After her husband’s death, Dorothy Thurman said, “He never seemed to regret not getting a chance earlier.”

But major-league baseball historians regret that we’ll never know what kind of career Bob Thurman would have enjoyed, if given an earlier opportunity.

This Bob Thurman biography is an adaptation of a profile in “The Black Stars Who Made Baseball Whole: The Jackie Robinson Generation in the Major Leagues” (McFarland & Co., 2006), by Rick Swaine. An updated version also appears in “Bittersweet Goodbye: The Black Barons, the Grays, and the 1948 Negro League World Series” (SABR, 2017), edited by Frederick C. Bush and Bill Nowlin.

Photo credit

Courtesy of Noir-Tech Research, Inc.

Sources

Boyle, Robert. “The Private World of the Negro Ballplayer,” Sports Illustrated, March 21, 1960.

Clark, Dick and Larry Lester, The Negro Leagues Book (Cleveland: SABR, 1994).

Lester, Larry. Black Baseball’s National Showcase: The East-West All-Star Game 1933-53 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001).

Obojski, Robert. “SCD profiles former Reds outfielder Bob Thurman,” Sports Collectors Digest, October 11, 1991.

James A. Riley, The Negro Baseball Leagues: The Biographical Encyclopedia, Carroll and Graf (1994)

Tygiel, Jules. Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997).

Young, A. S. “Doc.” Great Negro Baseball Stars (New York: A. S. Barnes, 1953.

The Sporting News

National Baseball Hall of Fame, miscellaneous clippings from Bob Thurman’s file.

Full Name

Robert Burns Thurman

Born

May 14, 1917 at Kellyville, OK (USA)

Died

October 31, 1998 at Wichita, KS (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.