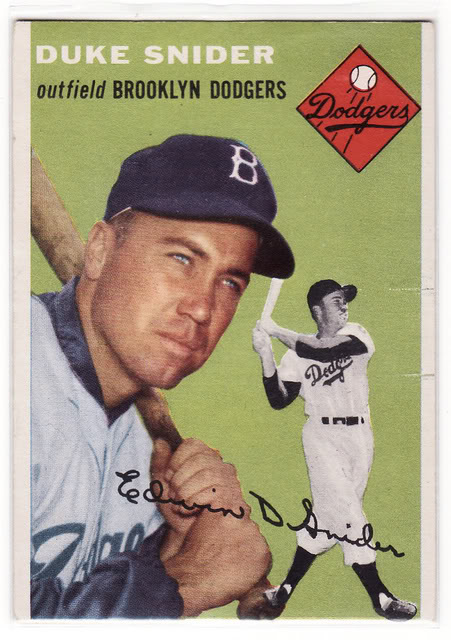

Duke Snider

A strong, accurate throwing arm, grace, and athleticism made Duke Snider one of the great center fielders of the 1950s. He played sixteen of his eighteen seasons for Brooklyn and Los Angeles, where his .300 batting average, 389 home runs, and 1,271 RBIs rank him as perhaps the greatest Dodger hitter ever. Blessed with remarkable ability, competitiveness, and a drive to succeed, Snider was also cursed with the tag of unlimited potential.

A strong, accurate throwing arm, grace, and athleticism made Duke Snider one of the great center fielders of the 1950s. He played sixteen of his eighteen seasons for Brooklyn and Los Angeles, where his .300 batting average, 389 home runs, and 1,271 RBIs rank him as perhaps the greatest Dodger hitter ever. Blessed with remarkable ability, competitiveness, and a drive to succeed, Snider was also cursed with the tag of unlimited potential.

Edwin Donald Snider was born to Ward and Florence Johnson Snider on September 19, 1926. He was their only child. Ward had been a semipro baseball player in his native Ohio Most accounts list Snider’s birthplace as Los Angeles, but according to writer Al Stump, he was born in Belvedere and grew up in Compton, a city surrounded by Los Angeles.

Nicknamed Duke by his father for his self-assured swagger, Edwin grew rapidly as he entered adolescence, reaching six feet in height and weighing 150 pounds in high school.

Duke participated in football, basketball, baseball, and track at Compton High School. He had a powerful arm, once throwing a 63-yard touchdown pass. He was high scorer on the same basketball team with Pete Rozelle, the future commissioner of the National Football League. On the baseball team he pitched and batted cleanup.

Snider performed well at a Dodgers’ tryout camp in Long Beach, California, and was offered a contract calling for a $750 bonus and a salary of $250 a month. The Pittsburgh Pirates subsequently offered him a $15,000 bonus, but Duke honored his Dodgers contract.

Invited to 1944 spring training at Bear Mountain, New York, Snider quickly demonstrated both his baseball talent and a difficult temperament. Cold and homesick—he failed to bring a coat—the seventeen-year-old moped instead of following directions to run laps. After apologizing for his behavior, Snider was inserted into the lineup against the West Point team and belted a long three-run homer. General Manager Branch Rickey profusely praised Snider’s power, arm, and the “steel springs in his legs.”

At the end of camp, Duke was sent to Newport News, Virginia, in the Class B Piedmont League where he played 131 games, batting .294 while leading the league with thirty-four doubles and nine home runs. In the outfield he compiled twenty-five assists.

Duke’s potential forced the Dodgers’ brass to overlook his growing pains. When manager Jake Pitler flashed a take sign, Snider became infuriated. Duke would return to the dugout and kick the water bucket in anger, demanding to be sent immediately to another team in the Dodgers’ organization. His temper erupted whenever he failed to connect at the plate. After his first season in professional baseball (which also included a brief stay with the Triple A Montreal Royals), Snider enlisted in the Navy, serving eighteen months during 1945 and part of 1946.

In 1946 he played sixty-eight games at Fort Worth in the Class AA Texas League. Though he batted only .250, Rickey was enthralled by Snider’s potential, his explosive swing, his grace in the field, and his blazing speed on the bases. Duke was considered the jewel of the Dodgers organization.

In 1947 Snider performed well enough in spring training to make Brooklyn’s opening day roster as a backup outfielder. He had his first major-league hit in his big-league debut—a single off Boston’s Si Johnson on April 17.

Jackie Robinson joined Snider in making the climb from the minor leagues to the big club that season. Duke, who admired Jackie for his courage and his athleticism, occasionally ate with him and kidded with him around the batting cage trying to ease the burden Robinson carried. When asked by some of his new teammates to sign a petition against Jackie, Snider refused.

Snider had a limited role with the 1947 Dodgers. In forty games, he hit .241 with twenty-four strikeouts in eighty-three at-bats as a pinch-hitter and part-time outfielder. While he struggled at the plate, he proved to be a gifted center fielder. But for all Snider’s gifts, he was immature, moody, and temperamental. Manager Burt Shotton, pegged Snider as a player who needed to be kicked to perform at his best.

On July 4 the Dodgers sent him to the St. Paul Saints of the American Association. There he hit .316 with twelve home runs in sixty-six games. He returned to the Dodgers at the end of the season and was a spectator at their World Series defeat by the Yankees. Snider received a quarter-share of World Series money. After the season, he married Beverly Null, his high-school sweetheart. (They raised four children, Pam, Kurt, Kevin, and Dawna.)

Rickey decided to teach the strike zone to Snider as a way to help his most gifted player harness his abundant potential. At spring training in 1948, Rickey and batting coach George Sisler worked intently with Snider to correct his tendency to lunge and overswing at the plate. The work was slow and difficult but Snider learned the strike zone. Spring training in 1948 was the turning point of Duke’s career. He later told Rickey’s biographer Murray Polner, “Without (Rickey), I would never have made it.”

Snider was assigned to Montreal to start the season in the International League. In games, he hit .327 with seventeen home runs and seventy-seven runs batted in. According to writer Ray Robinson, Duke once refused to bunt when ordered to do so by Montreal manager Clay Hopper. Instead, Snider angrily swung away, blasting a home run. Snider apologized to Hopper, who fined Duke for missing a sign and chastised him for his insolent behavior.

On August 6 Snider was recalled to Brooklyn. He played in fifty-three games, batted .244, and hit the first five home runs of his eighteen-year major-league career. Duke soon found Ebbets Field to his liking. It was tailor-made for a left-handed pull hitter. Snider could take aim at a right-field fence just 297 feet from the plate. At the start of the 1949 season, Shotton told him he would be the everyday center fielder and bat third until he demonstrated he was unable to do the job. With growing confidence, Duke proved that he belonged with the Dodgers, hitting a solid .292, with ninety-two RBIs, while tying Gil Hodges for the club lead with twenty-three home runs.

The Dodgers and the Cardinals went down to the last day of the season in a fight for the pennant. Duke came to the plate in top of the tenth inning of a 7–7 game with Philadelphia and stroked a single up the middle that scored Pee Wee Reese with the run that clinched the pennant for the Dodgers.

In the World Series the Dodgers fell to the Yankees in five games. Snider had a terrible Series, striking out eight times in the five games to tie a record held by Rogers Hornsby. Duke was only 3-for-21 at the plate, and failed to drive in a single run.

On May 30, 1950, in the second game of a doubleheader at Ebbets Field, Duke had one of the greatest games of his career. Facing Philadelphia’s Russ Meyer, Snider hit long home runs over the right-field screen onto Bedford Avenue in the first and third innings. In the fifth he smacked a Blix Donnelly pitch over the center-field wall for his third home run of the game. In his fourth at-bat, against Bob Miller, Duke hit a rising line drive that struck one foot below the top of the right-field screen. The ball was hit so hard that he was held to a single.

Snider went on to bat .321 and finish in the National League’s top five in eight offensive categories, leading in hits (199) and total bases (343). The 1950 season was almost a repeat of 1949 as the Dodgers came down to the last day of the season needing a victory to force a playoff for the pennant. Brooklyn was hosting the Phillies, whom they trailed by one game in the standings. With runners on first and second in the ninth inning of a 1–1 game, Duke lined a hit to center field off Robin Roberts. Center fielder Richie Ashburn gathered Snider’s hit on one bounce and easily threw out Cal Abrams, the runner from second, at the plate. In the top of tenth Dick Sisler hit a three-run homer to defeat the Dodgers and clinch the pennant for Philadelphia.

Snider’s batting average declined to .277 in 1951. He still managed to hit twenty-nine home runs and drive in 101 runs. In fourteen fewer at-bats than in 1950, Snider had eighteen more strikeouts and grounded into fourteen more double plays. Duke was disappointed in his failure to produce down the stretch when seemingly one big hit might have helped the Dodgers clinch the pennant. Brooklyn had gotten off to a hot start under manager Charlie Dressen, building a thirteen-game lead over the Giants by August 11. But the Giants won thirty-seven of their last forty-four games to tie for first place and force a best-of-three playoff for the pennant.

The Giants and Dodgers split the first two games. Game Three was played at the Polo Grounds. The Dodgers took a 4–1 lead into the bottom of the ninth. Bobby Thomson’s home run capped an amazing rally to lift the Giants into the World Series. As the ball cleared the left-field fence, Snider dropped to a knee and slammed his glove against the ground in frustration.

At the age of twenty-five, Duke’s hair was already turning gray. After the 1951 season he asked to be traded. Duke felt unable to live up to the high expectations associated with playing in New York. The Dodgers had no intention of parting with Snider and attempted to reassure him.

His teammates considered Snider a crybaby, a pouter with a personality problem, and a spoiled mama’s boy. Finally even Reese, the mild-mannered team captain, denounced Snider’s behavior, telling him to grow up and stop his moaning.

In 1952 Dressen benched Duke during an August slump. Eventually Snider returned to the lineup and led the Dodgers to the pennant and another World Series date with the Yankees. Over the last six weeks of the season, he raised his final average to .303, while chipping in twenty-one homers and ninety-two runs batted in.

In the sixth inning of the first game, in Brooklyn, Duke hit a two-run homer against Yankees ace Allie Reynolds. He had his best performance in Game Five at Yankee Stadium. He belted a 420-foot, two-run homer off Ewell Blackwell in the top of the fifth inning and then made a leaping catch of Yogi Berra’s hot liner in the bottom of the inning. After the Yankees took the lead, the Dodgers came back to tie the game in the seventh on Snider’s hit. The game went into the eleventh inning, when Snider doubled off the bullpen railing to score Billy Cox with the winning run. After five games, the Dodgers held a 3–2 lead with the final two games scheduled in Brooklyn.

In the sixth game Snider slugged solo home runs in the sixth and eighth innings. But the Dodgers lost, 3–2. In the final contest, Snider popped out against Yankees reliever Bob Kuzava with the bases loaded in the seventh inning. Kuzava blanked the Dodgers over the final two innings and clinched the championship for the Yankees. Still, Snider had a tremendous Series, going 10-for-29 with four home runs and eight RBIs. He felt he had truly arrived as a major-league player.

The next season, 1953, was the first of Snider’s five consecutive forty-plus home-run seasons. At twenty-six years old and entering the prime of his career, Duke finished in the top four in ten offensive categories and placed third in the MVP balloting. He hit .336 with 198 hits, forty-two home runs, 126 RBI, and sixteen stolen bases. He led the league in runs scored (132) and in slugging (.627). The Dodgers repeated as pennant-winners but again were beaten by the Yankees in the World Series. Snider was 8-for-25 with one home run and five RBIs in six games.

Snider had another outstanding season in 1954. He tied Stan Musial for the league lead with 120 runs scored and finished third in batting average, second in RBIs, and among the top three in six other offensive categories. Duke battled the Giants’ Don Mueller and Willie Mays for the batting title. The three were virtually tied going into the final day of the season, but Duke’s 0-for-3 left him third in the race at .341, his career high.

Snider made perhaps his most memorable defensive play in a game at Philadelphia’s Connie Mack Stadium on May 31, 1954. With two outs in the bottom of the twelfth inning, the Dodgers clinging to a 5–4 lead, and the potential tying and winning runs on base, Willie “Puddin’ Head” Jones hit a scorching shot to left-center field. Snider raced to his right, dug his spikes into the fence and leaped skyward while extending his glove as high as he could stretch his arm. He made a sensational one-handed catch to preserve the Dodgers’ victory before crashing to the turf.

Snider’s one defensive shortcoming was with groundballs; he rarely charged them despite repeated admonitions from Reese. Word quickly spread around the league. Runners would not even hesitate at second on a groundball to the outfield, consistently taking the extra base when the ball was hit to Snider, despite his strong throwing arm.

In 1955, Duke had his fourth season with a .300 batting average, thirty or more homers, and 100 or more RBI. He led the National League in runs scored (126) and RBI (136) while hitting .309 and blasting forty-two home runs. Snider was honored as The Sporting News Player of the Year. His teammate, Roy Campanella, edged Duke by five points in the balloting for the Most Valuable Player award. Individual statistics and honors paled in comparison to the team’s accomplishment as Brooklyn won its first and only World Series championship.

After a sensational first half, Snider was the starting center fielder for the National League in the All-Star Game. After the All-Star break, he slowed down. One day he was booed vociferously. He erupted in the clubhouse, telling anyone within earshot that the Brooklyn fans were the worst in the league. Reese attempted to intercede with the writers on Duke’s behalf, saying that Snider was upset and didn’t mean it. Snider insisted that he meant every word and wanted his temperamental outburst printed. When he took the field the next day, the Brooklyn faithful booed Snider as never before. Duke responded with three hits, turning the catcalls into cheers.

The pennant-winning Dodgers again took on the Yankees in the World Series. In the third inning of Game One in Yankee Stadium, Snider belted a solo home run off Whitey Ford that hit the third deck in right field, but the Dodgers lost, 6–5.

Game Four was played in Ebbets Field. Snider connected for a three-run home run off Johnny Kucks that dented an automobile on Bedford Avenue. The 8–5 Dodger victory squared the Series at two games apiece.

In Game Five, the Dodgers won, 5–3. Yankees starter Bob Grim threw Duke an inside curveball in the third inning and an outside curveball in the fifth inning. Each time Snider pounded the pitch over Ebbets Field’s right-field screen for a solo home run, becoming the first player to hit four home runs in two different World Series.

The Dodgers lost Game Six, 5–1, to tie the Series at three victories apiece. Snider was injured in the Yankee Stadium outfield after stepping on a wooden sprinkler cover and twisting his left knee. He was forced to leave the game after three innings. Despite his injured knee, Duke was in the lineup for Game Seven. He went 0-for-3, but Johnny Podres shut down the Yankees, 2–0. Snider was 8-for-25 in the Series with seven RBIs.

The 1956 release of a magazine article written with Roger Kahn, “I Play Baseball for Money, Not Fun,” reinforced a perception that Duke was immature, self-absorbed, and whiny. More than fifty newspaper articles castigated Snider, calling him a brat and a problem child for his complaints about the travel, the time away from his growing family, abuse from fans, the weight of unfulfilled expectations, and his desire to leave baseball to grow avocados. Snider had recently purchased sixty acres in Fallbrook, California, north of San Diego, where he had begun to plant avocados with his partner, former Brooklyn catcher Cliff Dapper.

One criticism that especially bothered Snider was that he benefited from being the only left-handed hitter in a lineup of strong right-handed batters, and that he was ducking left-handed pitchers. Years after his playing career ended, Snider vehemently rejected this charge, pointing to his .308 average against southpaws in 1954.

Brooklyn captured their sixth pennant in ten seasons in 1956. In the decisive final game, Snider hit two home runs, drove in four runs, and made a spectacular catch to stifle a Pittsburgh rally. While his batting average dipped below .300 (.292), he still managed to connect for forty-three home runs, a career best that led the National League. Snider drove in 101 runs, his sixth season topping the century mark.

The Dodgers and the Yankees met again in the World Series. Snider went 7-for-23 with four RBI, batting over .300 in his fourth consecutive World Series, but the Yankees recaptured the world championship in seven games.

The Dodgers won five National League pennants and placed second three times from 1949 through 1956. But 1957 was the end of an era. The Dodgers fell to third place, eleven games behind Milwaukee. Snider played in 139 games as his knee continued to bother him. (He had surgery after the season.) He hit forty or more home runs for the fifth consecutive season, tying the National League record held by Ralph Kiner (surpassed by Sammy Sosa, 1998-2003). Snider was the last player to homer at Ebbets Field, slamming two home runs off Philadelphia’s Robin Roberts on September 22. He was also the first batter to hit forty home runs while driving in fewer than 100 runs (he had 92).

After the 1957 season, the Dodgers and the Giants left New York to continue their rivalry in California. Although born and raised in Southern California, Snider hated to leave Brooklyn, where he had many friends and fans. He left behind memories of great performances and a unique ballpark seemingly built for his multitalented game.

Los Angeles welcomed Snider as a native Californian. As the best-known player in Los Angeles, he had a daily radio show and earned the highest salary on the team ($46,000). The Dodgers played in the Los Angeles Coliseum, an aging, oval-shaped, 90,000-seat football stadium built to host the 1932 Olympics. Duke was the only Dodger to hit a home run over the right-center-field fence during the 1958 season. The vast distances to center field, right-center, and right field negated Snider’s ability to pull the ball with power.

Duke played 106 games in 1958 as he suffered from a recurrence of knee trouble after a spring training auto accident, a back injury, and an arm strain. He was the only regular to hit over .300, batting .312, but saw a precipitous decline in home runs (from 40 to 15) and RBI (from 92 to 58). The aging Dodgers registered their worst record since 1944, finishing seventh, two games ahead of the last-place Phillies. With more than 1.8 million paid admissions, the Dodgers’ first season in their new home was a financial success, but a failure on the field.

With twenty cortisone shots for his ailing knee, Snider played in 126 games in 1959. He was still a fine outfielder, but to take some of the stress off his knee, he began playing in right field and left field, where less running was required. Snider topped .300 for the seventh time (.308), tallied twenty-three homers, and led the team with eighty-eight RBIs, despite striking out in nearly 20 percent of his at-bats.

In 1959 the Dodgers ended the season in a tie with Milwaukee. They swept the Braves in a two-game playoff and then defeated the Chicago White Sox in six games to win the World Series. Snider hit his final Series home run in Game Six in Chicago, off Early Wynn. Snider’s World Series totals include a .286 batting average with eleven home runs and twenty-six RBIs in thirty-six games.

Snider’s career was now winding down. Slowed by knee trouble, he hit only .243 in 1960 and was sent to the bench to make way for youngsters Tommy Davis and Willie Davis. On April 17, 1961, Snider hit his 370th home run to pass Ralph Kiner on the all-time list. In his next at-bat, Duke suffered a broken right elbow when Bob Gibson hit him with a pitch. Playing only eighty-five games that season, Snider platooned in the outfield with his roommate, Ron Fairly, and with Frank Howard.

By 1962 Snider, Jim Gilliam, and John Roseboro were the only position players remaining from Brooklyn. In honor of his sixteen years with the Dodgers, Duke was named captain of the team. Wearing white sideburns and a bit stout at thirty-five, Snider collected the first Los Angeles hit in the new Dodger Stadium on April 10. On May 30, the Dodgers made their first trip to the Polo Grounds to play the newly-created New York Mets. Duke received a thunderous ovation when he smashed a batting-practice home run.

Snider came to the plate only 158 times in 1962, batting .278 with just five home runs. At one point in the season, Duke did not leave the bench to play defense for seven consecutive weeks. After the Dodgers lost another three-game playoff to the Giants, rumors began to circulate that Duke had played his final game for Los Angeles. Upon the Dodgers’ arrival in Albuquerque for an exhibition game on April 1, he learned that he had been sold to the Mets.

Snider considered retirement, but general manager Buzzie Bavasi encouraged Duke to continue his career with the Mets. Snider needed five more hits to join the 2,000-hit club, and eleven more home runs to reach 400, a dual feat accomplished by only six other batters in baseball history at that time. Snider was also promised a job with Los Angeles upon the completion of his playing career, assuaging some of his hurt over the sale.

Snider played in 129 games for the Mets, his highest total since 1957. For sentimental reasons, the New York fans were happy to see Duke back in New York, but his past greatness was a distant memory. Although he was in good condition, his aching legs prevented him from running in the outfield and on the bases with anything approaching his previous panache.

Batting .243 in 354 at-bats, Duke did blast fourteen home runs to achieve 403 for his career. On April 11 he hit his first home run as a Met, off lefty Warren Spahn. Five days later Jim Maloney was the victim of Snider’s 2,000th base hit. His 400th home run was hit off Bob Purkey on June 14.

Snider decided to play in 1964, but asked the Mets to trade him to a contender so he might have a chance to participate in one more World Series. The Dodgers expressed some interest in reacquiring him, but before a deal could be struck, the Mets sold Snider to the Giants. It was shocking to conceive of Snider playing for the Dodgers’ great rival. With four children to support, Duke took the sale in stride. He was glad for the chance to return to California and be closer to his family.

Beverly and the children remained at home in Fallbrook, California, during the school year, while Duke lived by himself in an apartment. Snider mostly pinch-hit for the fourth-place Giants, batting a career-low .210 in just 167 at-bats. He collected the final four home runs of his career.

In addition to his avocado ranch, Snider had invested in a bowling center in Fallbrook. The bowling center was not a success and closed. Snider also had to sell his beloved ranch. He continued to live in Fallbrook but with the end of his active playing career, he needed to work to support his family.

Duke returned to the Dodgers, scouting and managing in the minor leagues through 1968. In 1969, he moved to the San Diego Padres, rejoining Buzzie Bavasi. Snider broadcast Padres games for three years, then served as a batting instructor. In 1973, he became a broadcaster and part-time batting instructor for the Montreal Expos.

Snider first became eligible for election to the Hall of Fame in 1970, but perhaps because of his difficult relationship with the writers, or because there was a sense that Duke failed to reach his potential, he garnered only 17 percent of the vote that year. His percentage gradually rose until in 1980, he received 86 percent of the votes (75 percent was needed) and was elected to the Hall.

During the 1981 major-league baseball strike that cancelled one third of the season, Terry Cashman wrote a song that paid tribute to the baseball stars of the 1950s. Talkin’ Baseball became a smash hit and kept Duke Snider in the forefront of public consciousness. Cashman saluted the three Hall of Fame center fielders using the choral refrain, “Willie, Mickey, and the Duke.” Another triumph for Snider during the decade was the publication of his bestselling autobiography, The Duke of Flatbush.

Duke retired from the Expos after the 1986 season. He suffered a heart attack in 1987, lost twenty-five pounds and underwent valve replacement surgery. His legs continued to bother him and he had to give up golf, eventually undergoing additional surgeries.

In the 1980s and 1990s, the growing baseball memorabilia business afforded retired players the chance to earn thousands of dollars for appearing at card shows and signing autographs. As a Hall of Fame member, Snider was in demand. But he took some of his appearance fees in cash and failed to declare those payments on his income-tax returns. In 1995, he and fellow Hall of Famer Willie McCovey were indicted for tax evasion. Both pleaded guilty, and Snider cooperated with the investigation to avoid jail time.

At his sentencing in federal court in Brooklyn, Snider admitted failing to report more than $100,000 in income from promotional appearances and card shows from 1984 to 1993. He was given two years’ probation, fined $5,000, and ordered to pay as much as $57,000 in back taxes, interest, and penalties. Snider apologized, accepting responsibility for his actions. His reputation damaged, Snider told reporters that he made the wrong choice.

After suffering for years with diabetes, hypertension and other illnesses, he died February 27, 2011, at age 84, in Escondido, California.

While statistics were important to Snider as evidenced by his decision to continue his career with the Mets to achieve 400 home runs and 2,000 hits, being part of a winning team gave him his greatest fulfillment. Duke Snider always will be remembered fondly in Brooklyn as the catalyst for the Dodgers’ greatest moment, victory in the 1955 World Series.

Sources

A Baseball Century: The First 100 Years of the National League. New York: Macmillan, 1976.

Allen, Lee. The Giants and the Dodgers: The Fabulous Story of Baseball’s Fiercest Feud. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1964.

Anderson, Dave. Pennant Races: Baseball at its Best. New York: Doubleday, 1994.

Angell, Roger. The Summer Game. New York: Popular Library, 1972.

Barber, Red. 1947: When All Hell Broke Loose in Baseball. New York: Da Capo Press, 1982.

Chalberg, John C. Rickey and Robinson: The Preacher, the Player, and America’s Game. Wheeling, IL: Harlan Davidson, 2000.

Cohen, Stanley. Dodgers! The First 100 Years. New York: Carol, 1990.

Daley, Arthur. Sports of the Times: The Arthur Daley Years. New York: Quadrangle/The New York Times Book Company, 1975.

Drees, Jack, and James C. Mullen. Where is He Now? Sports Heroes of Yesterday Revisited. Middle Village, NY: Jonathan David, 1973.

Drysdale, Don, with Bob Verdi. Once a Bum, Always a Dodger. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1990.

Durslag, Melvin. “Manager with a Hair Shirt.” In Jim Bouton with Neil Offen, I Managed Good but Boy, Did They Play Bad. Chicago: Playboy Press, 1973.

Enders, Eric. 1903-2003: 100 Years of the World Series. New York: Barnes and Noble, 2004.

Falkner, David. Great Time Coming: The Life of Jackie Robinson from Baseball to Birmingham. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995.

Fischler, Stan. Showdown: Baseball’s Ultimate Confrontations. New York: Grosset and Dunlap, 1978.

Forker, Dom. The Men of Autumn: An Oral History of the 1949-1953 World Champion New York Yankees. New York: New American Library, 1989.

Frommer, Harvey. New York City Baseball: The Last Golden Age 1947-1957. New York: Macmillan, 1980.

Frommer, Harvey. Rickey and Robinson: The Men Who Broke Baseball’s Color Barrier. New York: Macmillan, 1982.

Gergen, Joe. Greatest Sports Dynasties. St. Louis: The Sporting News, 1989.

Goldblatt, Andrew. The Giants and the Dodgers: Four Cities, Two Teams, One Rivalry. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2003.

Goldstein, Richard. Spartan Seasons: How Baseball Survived the Second World War. New York: Macmillan, 1980.

Goldstein, Richard. Superstars and Screwballs: 100 Years of Brooklyn Baseball. New York: Dutton, 1991.

Golenbock, Peter. Dynasty: The New York Yankees, 1949-1964. New York: Berkeley Books, 1985.

Honig, Donald. Mays, Mantle, Snider: A Celebration. New York: Macmillan, 1987.

Honig, Donald. The October Heroes: Great World Series Games Remembered by the Men Who Played in Them. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1979.

Hoppel, Joe, and Craig Carter. The Sporting News Baseball Trivia Book. St. Louis: The Sporting News, 1983.

Hoppel, Joe, and Craig Carter. The Sporting News Baseball Trivia Book 2. St. Louis: The Sporting News, 1987.

Huhn, Rick. The Sizzler: George Sisler, Baseball’s Forgotten Great. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2004.

James, Bill. The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract. New York: The Free Press, 2001.

Kahn, Roger. Memories of Summer: When Baseball was an Art and Writing About it a Game. New York: Hyperion, 1997.

Leonard, John. “Franchise: Dodgerisms, Brooklyn and L.A.” In Daniel Okrent and Harris Levine, The Ultimate Baseball Book. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1981, 265-284.

Light, Jonathan Fraser. The Cultural Encyclopedia of Baseball. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2005.

Mantle, Mickey, with Mickey Herskowitz. All My Octobers: My Memories of 12 World Series When the Yankees Ruled the World. New York: Harper Collins, 1994.

Mays, Willie, with Lou Sahadi. Say Hey: The Autobiography of Willie Mays. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1988.

McNeil, William. F. The Dodgers Encyclopedia. Champaign, IL: Sports Publishing, 1997.

Nathan, David H. Baseball Quotations. New York: Ballantine Books, 1991.

Nelson, Kevin. The Golden Game: The Story of California Baseball. San Francisco: California Historical Society Press, Berkeley, CA: Heyday Books, 2004.

Nemec, David. Players of Cooperstown: Baseball’s Hall of Fame. Lincolnwood, IL: Publications International, 1994.

Nemec, David. “Seventh Inning: 1950-1959.” In Daniel Okrent and Harris Levine, The Ultimate Baseball Book. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1981, 247-264.

Nemec, David. 20th Century Baseball Chronicle: Year-by-Year History of Major League Baseball. Lincolnwood, IL: Publications International, 1993.

O’Connor, Anthony. Baseball for the Love of It: Hall of Famers Tell it Like it Was. New York: Macmillan, 1982.

Peary, Danny. Cult Baseball Players: The Greats, the Flakes, the Weird, and the Wonderful. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1990.

Pepe, Phil, and Zander Hollander. The Baseball Book of Lists. New York: Pinnacle Books, 1983.

Phillips, Louis, and Burnham Holmes. Yogi, Babe, and Magic: The Complete Book of Sports Nicknames. New York: Prentice Hall, 1994.

Polner, Murray. Branch Rickey: A Biography. New York: New American Library, 1982.

Prince, Carl. E. Brooklyn’s Dodgers: The Bums, the Borough, and the Best of Baseball 1947-1957. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Reidenbaugh, Lowell. Cooperstown: Where Baseball’s Legends Live Forever. St. Louis: The Sporting News, 1983.

Reidenbaugh, Lowell. Take Me Out to the Ballpark. St. Louis: The Sporting News, 1983.

Ritter, Lawrence. Lost Ballparks: A Celebration of Baseball’s Legendary Fields. New York: Penguin Studio Books, 1994.

Ritter, Lawrence, and Donald Honig. The Image of Their Greatness: An Illustrated History of Baseball from 1900 to the Present. New York: Crown, 1984.

Ritter, Lawrence, and Donald Honig. The 100 Greatest Baseball Players of All Time. New York: Crown, 1981.

Robinson, Ray. The Home Run Heard Round the World: The Dramatic Story of the 1951 Giants-Dodgers Pennant Race. New York: Harper Collins, 1991.

Rosenthal, Harold. The 10 Best Years of Baseball: An Informal History of the Fifties. Chicago: Contemporary Books, 1979.

Shatzkin, Mike. The Ballplayers: Baseball’s Ultimate Biographical Reference. New York: Arbor House, 1990.

Snider, Duke, with Bill Gilbert. The Duke of Flatbush. New York: Zebra Books, 1989.

Stout, Glenn, and Richard A. Johnson. The Dodgers: 120 Years of Dodgers Baseball. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2004.

Sullivan, Neil. The Dodgers Move West. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987.

Vass, George. The Game I’ll Never Forget. Chicago: Bonus Books, 1999.

Whittingham, Richard. The Los Angeles Dodgers: An Illustrated History. New York: Harper and Row, 1982.

Williams, Dick, with Bill Plaschke. No More Mr. Nice Guy: A Life of Hard Ball. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1990.

Durslag, Melvin. “The Duke and His Miseries.” Sport, June 1959, pp. 70-73.

Mann, Arthur. “The Dodgers’ Problem Child.” The Saturday Evening Post, February 20, 1954, pp. 27, 111-113.

Snider, Duke, with Roger Kahn, “I Play Baseball for Money, Not Fun,” Collier’s, May 23, 1956 pp. 42-45.

“Sport Visits the Duke Sniders’ Ranch,” Sport, May 1958 pp. 46-49.

Stump, Al, “Duke Snider’s Story,” Sport, September 1955.

“Duke Sale Bugs Buzzie; ‘We’d Have Bought Him!’” Sporting News, April 25, 1964.

“Duke Seventh on Homer List,” Sporting News, April 26, 1961.

“Duke Ties Mize in HR Log,” Sporting News, June 8, 1960.

Joseph P Fried, “Snider gets Probation and a Fine in Tax Scheme,” New York Times, December 2, 1995.

Joseph P. Fried, “Snider was Sentenced First. Who’s Next?” New York Times, December 5, 1995.

Bob Hunter, “Dodgers’ Snider Battles Tears in Saying ‘So Long,’” Sporting News, April 13, 1963.

Bob Hunter, “L.A. Fans Stage Dazzling Salute for Snider Night,” Sporting News, September 7, 1960.

Bob Hunter, “Snider Ties DiMaggio, Hits 361st Home Run of Career,” Sporting News, June 15, 1960.

Dick Kaegel, “Baseball Inducts Four in Shrine,” Sporting News, August 16, 1980.

Roger Kahn, “The Boys Turn 26: It was a Different Era in Baseball and No Book Captured its Characters and its Character in Quite the Same Style,” Los Angeles Times, February, 22, 1998.

Barney Kremenko, “Duke of Dodgerdom Still King in Gotham,” Sporting News, April 20, 1963.

Jack Lang, “Shrine Doors Open for Kaline, Snider.” Sporting News, January 26, 1980.

Jack McDonald, “Giants Obtain Duke to Strengthen Their Bid for King’s Row,” Sporting News, April 25, 1964.

Lowell Reidenbaugh, “Duke in His Finest Hour Remembers Rickey, Sisler,” Sporting News, January 26, 1980.

Steve Scholfied, “Fallbrook’s Duke Snider 80 and Going Strong,” North County Times, September 19, 2006.

Joe Sexton, “Tax Fraud: Two Baseball Legends Say It’s So.” New York Times, July 21, 1995.

Full Name

Edwin Donald Snider

Born

September 19, 1926 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

Died

February 27, 2011 at Escondido, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.