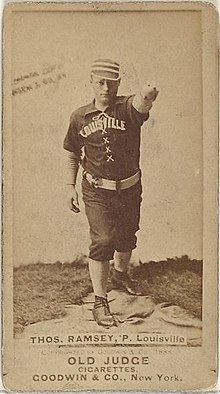

Toad Ramsey

Spin rate and rotation are buzz words of 21st century pitching, but they were just as important in the 19th century. Left-hander Toad Ramsey, who began his career in 1885, was renowned for the motion on his drop ball. “Toad Ramsey, beyond all doubt, had a patented drop ball rotating faster than any other, and this was caused by the enormous strength of Toad’s over-developed left fingers.”1 Noted early sportswriter Hugh S. Fullerton attributed those strong fingers to Ramsey’s upbringing when he was taught the masonry trade. He held the brick tightly in those left fingers while laying the mortar. Fullerton hyperbolized that Ramsey “almost could twist the cover off the ball by sheer strength.”2

Spin rate and rotation are buzz words of 21st century pitching, but they were just as important in the 19th century. Left-hander Toad Ramsey, who began his career in 1885, was renowned for the motion on his drop ball. “Toad Ramsey, beyond all doubt, had a patented drop ball rotating faster than any other, and this was caused by the enormous strength of Toad’s over-developed left fingers.”1 Noted early sportswriter Hugh S. Fullerton attributed those strong fingers to Ramsey’s upbringing when he was taught the masonry trade. He held the brick tightly in those left fingers while laying the mortar. Fullerton hyperbolized that Ramsey “almost could twist the cover off the ball by sheer strength.”2

Fullerton continued his praise of Ramsey, claiming that “his drop ball broke a foot and a half, his ‘in’ curve jumped two inches, and he pitched them both with the same motion.”3 Nineteenth century slugger Bobby Lowe claimed that the drop ball came to the plate “with as much speed as his fast ball, and just when it reached the batter it broke sharp, and fell almost straight.” Lowe went on to say, “There never has been a better left-hander than Ramsey in my opinion.”4

In 1886 and 1887 Ramsey (aged 21 at the opening of the 1886 season) tossed over 1,100 innings with the Louisville Colonels in the American Association and won 75 games. Those two seasons earned him far-ranging recognition as the greatest left-hander in the game. A hard-drinking lifestyle sent his career downhill rapidly and he won only 35 more games before leaving the major leagues after the 1890 season.

Thomas H. Ramsey was born August 8, 1864, joining his parents Thomas A. and Mathilda, and brothers Albert and William in Indianapolis.5 The elder Ramsey was a bricklayer and passed the trade on to his sons. The 1880 census lists Ramsey as attending school, which means he had more education than many youths of his day. He learned his baseball in Indianapolis and grew to be a stocky 5-feet-9 and 180 pounds. The redhead batted right-handed but was never known to be much of a threat with the ash.

Ramsey started to play for towns surrounding Indianapolis in 1883, most likely earning a few dollars each game. He spent a good deal of that summer with Shelbyville, Indiana, forming the battery with one of his brothers. In 1884 he was a member of the Rushville Blues. His work with Rushville caught the attention of the Indianapolis Hoosiers of the Western League. In the fall, they inked him to a contract for the 1885 season.6

Come spring, instead of staying home, Ramsey headed south to join Chattanooga in the Southern League and appeared in a few exhibition games before Indianapolis complained. The National Agreement, which both teams had accepted, called for an arbitration committee to solve conflicts involving dual contracts. His career was put on hold with until a decision was reached.7 The committee judged the Indianapolis contract to be not binding and awarded Ramsey to Chattanooga.8

His debut for the Lookouts was a loss to the Columbus (Georgia) Stars, who pounded out 12 hits for 13 runs. After that, Ramsey pitched well for Chattanooga but was surrounded by questionable fielding talent. He tossed a no-hitter on May 30 in Nashville. In early July, he threw a two-hitter at Macon and struck out 15 but took the loss, 5-3. His teammates made seven errors and catcher Sim Bullas had four passed balls.9

Ramsey teamed with 19-year-old Bill Hart as the aces of the pitching staff. Hart was 13-24 with a WHIP just over 1.00 and struck out 196. Ramsey tossed 354 innings, posting a 17-23 record with a 0.89 ERA. He struck out 387 with a WHIP of 0.78, second to John Hofford of Augusta in every category except losses.10

Ramsey left the team a couple of weeks before the close of the Southern League season. James A. Hart of the Louisville Colonels offered the Lookouts $300 for him. Chattanooga asked $1,000. Louisville wound up sending pitcher John Connor and $750 to the Lookouts.11

Ramsey signed a $200-a-month contract and joined the Colonels in time for the start of a month-long road trip. He debuted in St. Louis on September 5 and allowed the Browns just three hits but suffered a 4-3 loss when “his support was poor.”12 Four more losses followed before he finally picked up his first victory in Philadelphia on September 23, 10-5. He struck out 12 Athletics while adding a hit and a run scored.

A 3-2 loss to Philadelphia followed before two superb outings against last-place Baltimore. On September 28 he tossed a three-hitter and struck out 15 in a 4-2 victory. Two days later he struck out 10 in a seven-inning affair that Louisville won, 15-1. The season ended the next day and the Colonels slowly made their way back to Louisville, playing exhibitions along the way.

The Louisville fans finally got their first glimpse of Ramsey on Sunday, October 11, against Nashville of the Southern League. Ramsey wowed the home crowd with a 15-strikeout no-hitter in a 19-0 win. He was scheduled to start again on October 13 against the St. Louis Maroons who had finished last in the National League. Game time was 3:00 pm, but Ramsey was nowhere to be found. Finally, at 3:30 the game started with third baseman Phil Reccius in the box. Ramsey appeared in the second inning and was sent in to pitch. “He walked unsteadily into the box and with a kind of dazed air, tossed the first batter seven balls in succession, none of which came within a yard of the plate.”13

Hart fined Ramsey $50. In later years a curious story emerged as to how Hart handled his unpredictable and often inebriated southpaw after that. Some franchises wrote temperance clauses into a player’s contract. Hart surmised that this would not work for Ramsey. Instead he reportedly designed a contract that allowed Ramsey to drink with Hart’s permission so long as he was ready for game day. Reportedly Ramsey drank the least in 1886 than at any other time in his career.14

It would take more than abstention from drink on game days to turn Ramsey into a consistent winner. He had suffered with catchers who could not contain his pitches, especially the drop. In Louisville he was matched with John Kerins, who proved to be one of the few who could handle his assortment of pitches. The results were spectacular.

In a time when left-handed pitchers were something of a rarity, the American Association featured Ramsey, Matt Kilroy, and Ed Morris in 1886. Morris tied for the league lead in wins (41) with Ramsey in third place at 38. Kilroy had a losing record but fanned 513. Ramsey was second with 499. Ramsey led the league’s pitchers in complete games (66, tied with Kilroy), innings pitched (588 2/3) and walks (207). His WHIP of 1.111 was third in the circuit. The Colonels only won 66 games and played at a .485 clip in contrast to Ramsey’s .585 winning percentage.

Ramsey’s performance in 1886 had caught the attention of the baseball world and turned him into a star. He was given a raise for the 1887 season but faced uncertainty with a new manager and new rules.

The American Association and National League agreed on some rule changes for 1887. It would now take only five balls for a walk (it had been six in AA and seven in NL) while four strikes resulted in an out. The practice of calling for a high or low pitch was abolished, and a strike zone created. The size of the pitcher’s box and style of delivery were changed over the winter and adjusted in late May.

Manager Hart was replaced by John “Kick” Kelly. Kelly never had much of a professional playing career but had been a successful umpire for the past four seasons. He made it known quickly that he did not share Hart’s philosophy on how to handle drinkers. Since his roster included Ramsey and Pete Browning, once called “the two greatest lushers in the base ball profession,” he had his hands full.15

Ramsey tested his new manager in the exhibition season by going on a binge until three in the morning. Twelve hours later he was facing the Indianapolis Hoosiers and proceeded to lob the ball to the plate. His performance earned him his first $50 fine of the year.16

Not only did Kelly propose to handle Ramsey differently than Hart had, he announced early on that Kerins would be captain and play first base. This meant that the player most adept at handling Ramsey’s drop ball would not be his catcher. Kelly proposed to use Paul Cook and Amos Cross as the backstops.

Kelly’s plans for the catching corps were derailed when Cross suffered a shoulder injury. His brother Lave replaced him on the roster. Kerins opened the season as Ramsey’s personal catcher, returning to first base when Guy Hecker or Icebox Chamberlain pitched. That arrangement would last until an injury briefly sidelined Kerins in May.

Ramsey opened the season by beating St. Louis, 8-3. The Browns ran away with the pennant and tagged five losses onto Ramsey in the process. Ramsey had a 5-6 record when Kerins went down the first time. He had just lost his first match against his friend and fellow lefty, Kilroy of Baltimore, surrendering three runs in the ninth to lose, 6-5.

The fans and the press heralded these battles of the two top men in the Association. Kilroy would win 46 games, Ramsey 37. In almost every important statistical category (and the league standings) Ramsey finished behind Kilroy in 1887. The most glaring exception was in strikeouts where Ramsey held a 355 to 217 edge. Ramsey lost the first three confrontations with Kilroy before earning a win on July 17, and finished the year 4-3 in face-to-face games with Kilroy.17

With Kerins unavailable, Kelly had his choice of Cook, who was regarded as handling fast ball pitchers the best, or 21-year-old rookie Lave Cross. Cross was his catcher when Ramsey faced New York on May 21. The youngster struggled with Ramsey’s drop ball and committed five passed balls, but Louisville got the win. Cross caught Ramsey until Kerins returned on June 11.

For reasons unknown, Ramsey pitched four consecutive games in late June against Cincinnati, winning 3. He was being overworked. When statistics were published in Sporting Life a few weeks later, he had faced 1,293 batters while Kilroy had seen only 962.18

When Ramsey defeated Kilroy on August 21, he celebrated by joining Browning on a binge. Browning earned a $50 fine while Ramsey was slapped with an indefinite suspension. Ramsey pitched again on August 31 but only went two innings because of a sore arm. The overuse had finally caught up to him. He sat out a week before returning to action and posting a five-game winning streak.

Ramsey’s nickname “Toad” began to appear toward the end of the summer. A brief comment in Sporting Life suggested sportswriter Harry Weldon had coined it when Ramsey played with Shelbyville.19 The exact origins of the name are unknown and it is not certain whether it referred to a facial expression or was a spin on his given name of Thomas.

After a winter of press speculation that the Colonels would not be able to afford him, Ramsey was back with Louisville. Manager Kelly brought in 20-year-old Sam “Skyrocket” Smith to play first base with the goal to make Kerins a full-time catcher again. The team also re-signed Cook and Lave Cross.

Ramsey, Cook, and infielder Reddy Mack went to Hot Springs, Arkansas, to prepare for the next season. On March 23 a newspaper article reported that Ramsey had gotten drunk and been arrested by the police. Cook claimed the story was a concoction and the incident never happened. Kelly immediately telegraphed the trio to return to Louisville.20 He wanted them to join the rest of the team that was working in a gym in the mornings and running at Churchill Downs in the afternoons.

As the training camp wound down, Kelly brought in leading temperance evangelist Francis Murphy, who met with the players and got Browning, Mack, and Ramsey to take temperance pledges. Ramsey claimed he “was never more in earnest in his life and will live up to his word.”21 He let it be known that he was sponsoring a youth team that would play other young teens. Had he turned a page in his life?

Guy Hecker was now 32 and the Colonels looked to get younger by bringing in teenager Scott Stratton to join Chamberlain and Ramsey on the pitching staff. Chamberlain had other ideas and staged a holdout from his Buffalo home. Ramsey pitched the season opener in St. Louis. His drop ball was not working, and he was hit easily, losing 8-0. He took another loss to the Browns in the fourth game of the series.

The team moved on to Kansas City where Ramsey found the movement on his pitches, picking up his first win. He followed up with a win over Cincinnati in the home opener. Chamberlain returned in early May and fans hoped the team was ready to make a move in the standings.

The Colonels moved, but it was downward. Ramsey lost seven games in May, some by scores like 18-1 and 18-2. The team spent most of June in last place and was sold to a new ownership group. Kelly was replaced by team president and business manager Mordecai Davidson. There were rumors that Ramsey, Hecker, and Kerins had led a conspiracy to have Kelly replaced. 22

The team was struck with injuries and Ramsey abandoned his temperance pledge. He was drinking hard and begging for advances on his salary. Nevertheless, he showed flashes of brilliance on the field. In the second game of the July 4 doubleheader, he beat Baltimore, 4-1, and hit two doubles. He followed that performance with a shutout of Cleveland in which he got three hits. Ramsey always liked to brag about his hitting if he was successful. His teammates must have heard plenty from him after those two games.

Ramsey was not the only player to give Davidson headaches. In late July Davidson threatened that he would suspend any player who was not keeping in condition and under control. He started by indefinitely suspending Ramsey for the second time that season for missing the train to Cincinnati.23 Davidson made it known publicly that Ramsey was suspended without pay.

Ramsey was in debt around the city of Louisville. He owed upwards of $500 to various saloon keepers and the Fifth Avenue Hotel. When the creditors realized that Ramsey had no income they went to the police and had warrants sworn to arrest Ramsey for indebtedness. On July 25 he was arrested outside a tavern and taken to jail.24

The case played out in the local papers. Ramsey was released from jail after he declared insolvency. A talented (and unnamed) local lawyer came to his aid. The barrister threatened to sue the Colonels for denying Ramsey a livelihood. The goal was either reinstatement or release. He also claimed, “[T]he jailing of Ramsey for debts was an outrageous proceeding” and suggested that Ramsey could have a case for false imprisonment.25

The drama continued for another two weeks before Ramsey and Davidson met to find a resolution. At the conclusion of the meeting, Davidson reinstated his wayward lefty. Ramsey lost to Philadelphia on August 15, then pitched an exhibition against Cleveland the next day. It was lucky that the Colonels had him back in action because their roster had been decimated by injuries and transactions.

Louisville embarked on a lengthy road trip in late August with just 11 men. Stratton and Browning were the most notable who were left behind. To make matters worse, Chamberlain was sold to the St. Louis Browns after just a few games on the road. Lineups featured catchers at shortstop (Cook) and the outfield. Ramsey even patrolled the outfield. They eventually added a few minor leaguers to flesh out the roster. The team struggled to a 5-18 record on the trip that included Ramsey’s loss to Chamberlain on September 12. Louisville closed the year at 48-87, Ramsey posted a dismal 8-30 record.

The Colonels’ situation continued to degrade in 1889. They dropped their first six games and spent nearly every day of the season in last place. Their record of 27-111 was one of the worst in history.26 Ramsey posted a 1-16 record with the worst ERA and WHIP of any Colonel with 50 or more innings of work.

Management had been shopping Ramsey for a year. The initial price tag was $10,000 or a frontline starter. By mid-July the Colonels were so desperate to rid themselves of Ramsey he was traded to the Browns for seldom-used, dead-armed pitcher Nat Hudson. Indicative of how the Colonels’ fortunes were, Hudson refused to report.

Hudson’s refusal led to a two-week delay before Ramsey was placed on the Browns roster. He only appeared in five games and posted a 3-1 record. One of those victories came on September 30 when he beat the Colonels.

The Browns lost manager/first baseman Charles Comiskey to the Players League in 1890 and suffered an even bigger loss when he took staff ace Silver King and slugger Tip O’Neill with him. St. Louis had pitchers Jack Stivetts and Chamberlain but needed Ramsey to return to his early form in order to compete. Reports had circulated that Ramsey had spent the winter sober, giving the fans hope, but in March he telegraphed that he would not be in camp on time. He claimed to have been sick for a few weeks.27 Was this really an illness or had he fallen off the wagon?

Once in camp, Ramsey put the fears to rest. He displayed professionalism, good conditioning, and an early command of his pitches. One writer speculated that “it is possible he has set his head to do what he wants to — redeem his reputation and again become one of the stars of the profession.”28

The Browns opened the year in Louisville. Ramsey took the box in the opener and “it was the Tom of yore.” He had the drop ball working, showed his deadly move to first base, and fumbled an easy grounder. A late rally gave the Browns an 11-8 win.29 Louisville captured the next three games before the Browns returned home to face Toledo. Ramsey picked up his second win, 6-5, then grabbed a third with a 5-1 defeat of Columbus.

The Browns faced Louisville and Ramsey lobbied to pitch at least three games. Instead he pitched only the first one, losing 6-3. He bounced back from the loss and on May 6 hurled his finest game of the year, beating Columbus, 7-0, with a one-hitter. The game was the first of a 23-game road trip. St. Louis struggled to a 10-13 record during the trip, falling off the pace being set by Louisville. They never could climb higher than second.

Ramsey reportedly kept away from the bottle that summer. He posted a 23-17 record but was released three weeks before the end of the season. Owner Chris Von der Ahe attributed his departure to bad fielding.30 Ramsey led league pitchers with 18 errors and was fielding at a .729 clip.

Toad never returned to the major leagues. Historians have suggested that he was unofficially blacklisted by the baseball establishment.31 There had been plenty of speculation that he might be blacklisted when he had been jailed in Louisville. That had since subsided. He was most likely a victim of downsizing — the Players League played only in 1890 and the American Association ceased business after 1891 — and his intemperate spirit.

Ramsey signed with Denver in the Western Association for the 1891 season. He struggled early, reportedly allowing 14 runs in an inning against Chicago in an exhibition. Records list him with only one appearance, but he was on the Denver roster until early July.32 It was reported he might join Hecker in Ft. Wayne.33

Over the winter in Indianapolis, Ramsey contacted Cleveland and Cincinnati hoping for a chance, but nothing developed. It was widely reported that he was working for the Louisville club as a concessionaire in April.34 In late June he reportedly signed with the Evansville Hoosiers but failed to see action.35 In July he joined Hecker, who was now managing the Jacksonville (Illinois) Lunatics in the Illinois-Iowa League. A 16-run pounding by Rockford ended that association.36

Ramsey returned to Indianapolis to live with the family. His father was ill and passed away in May 1893. Ramsey played and managed Shelbyville that summer, always hoping to be invited back to the professional level. In December 1893 it was reported that he had signed with the Sioux City Huskers for the coming season.37 That deal fell through and when spring came around Ramsey was headed to Georgia to play with the Savannah Modocs in the Class B Southern Association.

On his way south he stopped off in Louisville. He told reporters that he had not taken a drink in years. He appeared “harder, stronger and lighter than he ever had” when he played in town.38 He was now 29 years old, a time when many pitchers are in their prime.

Ramsey beat Charleston, 4-2, to give Savannah their first win of the young campaign on April 12. He posted eight wins in the first five weeks of the season. As talk of league finances and franchise closures mounted, he seemed to lose his interest and resolve. The losses started to pile up, including a 23-1 defeat by Memphis.

The Savannah franchise tried to hold on as other teams folded. They even played exhibition games against local teams on dates when Macon and other opponents had cancelled. In the end the league was reconfigured with only four teams and Savannah was left out of the mix. Ramsey contacted Indianapolis when the first signs of upheaval emerged but was turned down.

Ramsey signed with the Kansas City Cowboys of the Western Association.39 The Cowboys were desperate for pitching and made two other signings about the same time as Ramsey’s. The Cowboys liked Bill Kling more than Ramsey, who went home without seeing action. He tried one last time to get a chance with Indianapolis, offering his services for $100 a month and a train ticket but was again turned down.40

Ramsey joined the St. Joseph (Missouri) Saints in the Western Association in 1895. Baseball Reference lists him with four starts for the Saints, all of them complete games. A careful search of the St. Joseph Herald reveals that he did have four starts. However, he never made it past the sixth inning in any of the games. His last performance was so miserable that he was replaced after “one and three fourths innings [sic].”41 He was released in mid-June.

Ramsey tried his hand at umpiring in the Western League in 1896. The experiment lasted about a week.42 In 1899 manager Bob Allen invited Ramsey to training camp with his hometown team in the Western League. Others in camp included a young Doc Newton and the “Hoosier Thunderbolt,” Amos Rusie. Ramsey finally wore the Hoosiers colors, but only in an intra-squad game.43

Ramsey continued to live in Indianapolis and tended bar for his brother, William. He died from pneumonia on March 27, 1906, at the age of 41. His obituary in Sporting Life mentioned that he was survived by his wife Anna, but no details of their life together were uncovered.44 He was buried in the Crown Hill Cemetery in Indianapolis.

After Ramsey’s major-league career ended, tales of his exploits often made the newspapers. His strikeout prowess was usually mentioned. Catcher Kerins told a tale of him striking out 18 Browns in 1887. As with many baseball tales, there is some truth to the story, but it was embellished. Ramsey struck out 17 on June 21 against Cleveland, then set down 16 Browns on June 30.45 It took four strikes in those days and Kerins liked to speculate that those totals would have been in the 20s if it had only taken three strikes.46

Acknowledgments

This biography was edited by William Lamb and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Notes

1 William A. Phelon, “Some Incidents on the Diamond Which Never Happened Before,” Baseball Magazine, August 13, 1913: 50.

2 Hugh S. Fullerton, “Southpaws are Very Eccentric,” Buffalo Courier, January 21, 1906: 33.

3 Fullerton

4 “Greatest of Pitchers,” Buffalo Commercial, March 23, 1906: 6. It should be noted that Ramsey was not a flame thrower and in later years his drop ball was described as slow. Some historians have even claimed it was an early type of knuckle ball. Considering there was no mention of Ramsey when Lew Moren and Eddie Cicotte began using the knuckler in 1907-09 I tend to doubt Ramsey tossed the pitch. The talk of spin, speed, and control also argue against him throwing a knuckler which has no spin, is hard to control, and is certainly not fast.

5 His death certificate carries the birthdate of March 6, 1865. It was informed by his brother William. https://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?dbid=60716&h=1673905&indiv=try&o_vc=Record:OtherRecord&rhSource=2469. Last viewed March 7, 2020.

6 “Base Ball Intelligence,” Indianapolis News, November 19, 1884: 3.

7 “Diamond Dust,” Indianapolis Sentinel, April 20, 1885: 5.

8 “Ramsey Reinstated,” Chattanooga Times, April 21, 1885: 8.

9 “Southern League Games Elsewhere,” Public Ledger (Memphis, Tennessee), July 8, 1885: 2.

10 Using the ERA for comparison purposes seemed a bit futile. Ramsey gave up 177 runs — exactly 4.5 runs per 9 innings. However only 35 (a mere 20%) of those have been counted as earned.

11 “Ramsey’s Release,” Chattanooga Times, August 30, 1885: 8. Some writers have suggested this was the first true trade made in baseball history.

12 “St. Louis Defeats Louisville,” Indianapolis Journal, September 6, 1885: 8.

13 “Popular Sports,” Courier-Journal (Louisville, Kentucky), October 14, 1885: 2. In 1885 it took seven balls to walk in the AA and six in the NL.

14 Hugh S. Fullerton, “Odd Baseball Contracts,” Duluth (Minnesota) News-Tribune, January 13, 1907: 2.

15 “Sporting News,” Pittsburg Dispatch, March 24, 1890: 7

16 “Ramsey Fined $50,” Courier-Journal, April 10, 1887: 4.

17 As taken from box scores in Sporting Life.

18 “Pitcher’s Averages,” Sporting Life, July 13, 1887: 3.

19 “From Cincinnati,” Sporting Life, October 5, 1887: 3.

20 “The Diamond,” Courier-Journal, March 25, 1888: 16.

21 “All Sign the Pledge,” Courier-Journal, April17, 1888: 6.

22 “Louisville Laconics,” Sporting Life, June 20, 1888: 3.

23 “To Maintain Strict Discipline,” Courier-Journal, July 22, 1888: 2.

24 “Tom Ramsey in Jail,” Courier-Journal, July 26, 1888: 6.

25 “Ramsey May Sue the Club,” Courier-Journal, July 29, 1888: 7.

26 The 1899 Cleveland Spiders only had 20 wins and a .130 winning percentage. Louisville’s .169 win percentage was the third worst in history and made the 1962 Mets (.250) look competent.

27 “Base Ball Gossip,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, March 16, 1890: 10.

28 “Sporting” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, March 24, 1890: 6.

29 “The Season Opens,” Courier-Journal, April 19, 1890: 4.

30 “Ramsey Released,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, September 20, 1890: 7.

31 David Nemec, ed., Major League Baseball Profiles, 1871-1900, Volume 1, (University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln: 2011), 155.

32 “From the Athletic World,” Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Patriot, July 6, 1891: 3.

33 “Scraps of Sports,” St. Paul (Minnesota) Globe, July 19, 1891: 8.

34 The Diamond,” Pittsburg Dispatch, April 27, 1892: 8.

35 “Hard Hitting,” Evansville (Indiana) Journal, June 28, 1892: 6.

36 “A Pennant Winning Gait,” Daily Register-Gazette (Rockford, Illinois), July 18, 1892: 5.

37 “The Team Being Signed,” Sioux City (Iowa) Journal, December 17, 1893: 7.

38 “Tom Ramsey Looks Well,” Courier-Journal, March 9, 1894: 2. The following day the same paper noted that he weighed just 162 pounds.

39 “All After Wadsworth,” Indianapolis Journal, June 27, 1894: 4.

40 “Baseball Notes,” Indianapolis Journal, August 21, 1894: 2.

41 “Voriss was Rank,” St. Joseph (Missouri) Herald, June 12, 1895: 3. The other three games can be found in May 10 paper on page 2, the May 13 on page 3, and the June 1 on page 5.

42 “Hot Shots,” Covington (Kentucky) Post, August 7, 1896: 7.

43 “Swiftest This Spring,” Indianapolis Journal, April 24, 1899: 7.

44 “Tom Ramsey Dies,” Sporting Life, April 7, 1906: 8.

45 He did strikeout 16 Browns in a victory on June 30. “Diamond Sparks,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 1, 1887: 5.

46 “On the Ball Fields,” Omaha Bee, May 31, 1896: 20.

Full Name

Thomas H. Ramsey

Born

August 8, 1864 at Indianapolis, IN (USA)

Died

March 27, 1906 at Indianapolis, IN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.