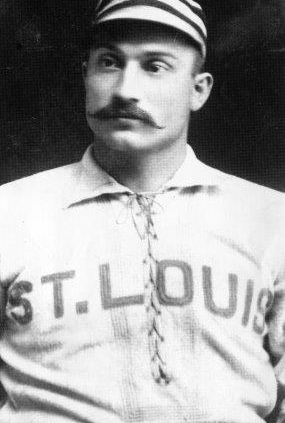

Jack Stivetts

He threw a ball as fast as Amos “The Hoosier Thunderbolt” Rusie, hit the ball as “hard as any man in the league,” and was versatile enough to play every position except catcher.1 His name was Jack Stivetts. In an 11-year major-league career that began with the St. Louis Browns of the American Association in 1889, he won 203 games and batted .298. His greatest fame came in 1892, his first year with the National League Boston Beaneaters. That season Stivetts tossed the first no-hitter in franchise history, en route to winning 35 games, then helped lead the club to its second of three consecutive titles in an extraordinary performance in a postseason championship series. Here’s the story of a forgotten nineteenth century hurler whose accomplishments deserve more recognition.

He threw a ball as fast as Amos “The Hoosier Thunderbolt” Rusie, hit the ball as “hard as any man in the league,” and was versatile enough to play every position except catcher.1 His name was Jack Stivetts. In an 11-year major-league career that began with the St. Louis Browns of the American Association in 1889, he won 203 games and batted .298. His greatest fame came in 1892, his first year with the National League Boston Beaneaters. That season Stivetts tossed the first no-hitter in franchise history, en route to winning 35 games, then helped lead the club to its second of three consecutive titles in an extraordinary performance in a postseason championship series. Here’s the story of a forgotten nineteenth century hurler whose accomplishments deserve more recognition.

John Elmer Stivetts was born on March 31, 1868, in Ashland, Pennsylvania. His parents were German-speaking immigrants; father Adam Stibitz emigrated from the Kingdom of Bavaria as a 20-year-old and arrived in New York in January 1854; mother Emilie Kupfer left the Kingdom of Prussia in October 1853.2 The Stibitz and Kupfer families soon thereafter settled in Ashland, in Schuylkill County, in hilly east-central Pennsylvania. The discovery of coal transformed the quiet rural village into a bustling boomtown, with population growing from about 200 in 1850 to almost 4,000 by the end of the decade. Like other immigrants with limited education and the additional challenge of a language barrier, Adam found work in the local anthracite coal mines. He and Amalia Cooper (Emilie’s anglicized name) welcomed at least 12 children into the world from about 1859 to 1877, though not all survived infancy. They spoke German at home with their children. At some point after the 1880 US Census, the family changed its surname to Stivetts.

Had it not been for baseball, Jack, as he was called, was destined to spend his life underground in coal mines where he had already begun to work by the time he finished the eighth grade. Tall and sturdily built, Jack played town ball for Ashland, making a name for himself as both a pitcher and batter. His professional career began in 1887 when Ashland became one of eight founding members of the Central Pennsylvania League, whose teams played an imbalanced schedule of about 40-50 games. The following season, he moved to the Allentown Peanuts of the Central League. Though complete statistics are not available for Stivetts’ first three professional seasons, he must have been a sensation in 1889 as a member of the York (Pennsylvania) club in the Middle States League. According to historian Robert L. Tiemann, Stivetts went 15-3 and yielded just one earned run in his last nine starts.3 In an exhibition game against the St. Louis Browns (renamed the Cardinals in 1900) of the America Association, Stivetts caught the attention of the club’s player-manager, Charlie Comiskey, who supposedly secured his contract on the spot, in June 1889.4

Stivetts landed on the American Association’s best team, which Comiskey had guided to the last four league titles. The Browns’ success was also the product of their brash German-born owner, Chris von der Ahe, who knew little about baseball. A tireless marketer and self-promoter, von der Ahe helped establish the American Association as a major league to rival the National League by then-unconventional tactics, such as selling beer at games, playing on Sunday, and advertising the games to the average working man and not just high society. The Browns were once again engaged in a fierce pennant race with the Brooklyn Bridegrooms. The 21-year-old Stivetts was brought along slowly behind the team’s two primary hurlers (also 21 years old), Silver King and Ice Box Chamberlain, who finished with 35 and 32 victories respectively. Stivetts, said Sporting Life, made a “good impression” in his debut, against the Cincinnati Red Stockings on June 26, yielding just one earned run and fanning nine in a 6-1 loss.5 Four days later, he did “remarkable work” and showed “great speed” in notching his first win, 12-7 over the Louisville Colonels, whiffing nine.6 When King complained of a sore arm on July 13 at Sportsman’s Park in the Gateway City, Stivetts was the emergency starter, going the distance in the team’s highest-scoring contest of the year, a 25-5 victory over the Baltimore Orioles. The Browns seemed destined to capture their fifth consecutive title before hitting a rough patch beginning with an extended road swing on August 30, losing 10 of 16 games, to fall 4½ games behind Brooklyn. Despite winning 13 of their last 14 games (one tie), the Browns finished in second place, two games behind the Bridegrooms. Stivetts (12-7) had the lowest ERA (2.25) among qualified pitchers in the league; however, his 191⅔ innings pale in comparison to King (458), Chamberlain (421⅔), and league leader Mark Baldwin (513⅔) of the Columbus Solons.

The Browns’ chances to reclaim the title in 1890 were slashed in the offseason when Comiskey and King broke their reserve clause and jumped to the Chicago Pirates in the newly formed Players’ League.7 The league, an outgrowth of baseball’s first union (the Brotherhood of Professional Base Ball Players), attracted many of the biggest stars in the sport, and placed yet further pressure on the two established major leagues, the NL and AA, to raise salaries. The loss of King and the early-season trade of Chamberlain enabled Stivetts to showcase his talents as one of the Browns’ two front-line pitchers. Described by St. Louis sportswriter Joe Pritchard as the “lawn mower” for the way he made batters reach around for his fastball, Stivetts continued his ascendance as one of the circuit’s top twirlers.8 At 6-feet-2 inches and weighing 200 pounds, Stivetts cut an imposing presence on the mound; his heater and just enough wildness made him one of the most dangerous hurlers in the league. On April 27 he tossed a four-hitter to beat Columbus, 14-1, and punched out 12 with a ball that looked like a “fly speck” when it crossed the plate, thought the Solons manager Al Buckenberger.9 Stivetts also emerged as a serious threat at the plate. On June 10 he tossed a complete game and whacked two home runs, including a game-winning grand slam in the ninth inning against the Toledo Maumees.10 The Browns (77-58) finished in third place, winning less than 60 percent of their games for the first time since 1882, the inaugural season of the AA. By the end of the season, Stivetts’ (27-21, 3.52 ERA in 419 innings and 41 complete games) name was plastered among the leader boards. He also rivaled Count Campau as the team’s most feared hitter, slugging .500 with seven home runs, and played in the outfield or at first base in 13 games.

In the offseason, the Players’ League collapsed and many of the top drawing cards returned to the AA in 1891, though not necessarily to their original teams. With Comiskey back as skipper and playing first base, the Browns flirted with first place until mid-August, when the Boston Reds pulled away and captured the pennant by 8½ games over the Browns. The team’s biggest news item was Stivetts, and not only because of his work on the diamond. He once again placed in the top five in almost every significant pitching category, winning 33 games with a 2.86 ERA in 440 innings, and paced the circuit in strikeouts (259) and walks (232). He batted .305 and played 24 games in the outfield.

Known as “Happy Jack” for his carefree disposition and wide grin, Stivetts had an ornery and combative streak, especially when he drank too much alcohol. In late June 1891, he and roommate Joe Neale, who lived above a tavern across from Sportsman’s Park at Grand and St. Louis Avenues, were hauled off to the police station in the middle of the night for their loud excessive behavior, but were not charged with an offense.11 The St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported on August 20 that Stivetts got “very drunk” at a lawn party after the Browns game was rained out.12 Never afraid to make his opinions known, Stivetts confronted von der Ahe, with whom he had a prickly relationship like many other Browns players. Von der Ahe ultimately called the police on Stivetts, who drew a short suspension from the owner. The big pitcher was hardly fazed by the incident or its results; “Der Boss,” as von der Ahe liked to call himself, had suspended him other times for his “drunken carousals” and “disgraceful behavior,” only to bring him back a game or two later when he was scheduled to pitch.13

Late in the season, rumors swirled that Stivetts had signed a contact with the NL’s Boston Beaneaters for 1892. The American Association had been gradually imploding all season long, doomed by contract jumpers, an unwinnable financial struggle with the NL over quality players, and failure to win back the fans’ trust after so many stars had bolted to the Players’ League. At a meeting in Indianapolis in December, the AA and the NL agreed to merge. Clubs in St. Louis, Baltimore, and Louisville were admitted to the NL; the NL purchased the franchises in Chicago, Boston, Columbus, Milwaukee, and Washington, and their players were sold; and a new Washington team was awarded. The National League emerged as a 12-team monopoly.

Both the Browns and Beaneaters laid claims to Stivetts, who was awarded to the latter. The reigning NL champions already had two of the league’s best pitchers, veteran John Clarkson and 22-year-old Kid Nichols, both of whom won at least 30 games in 1891; however, Sporting Life noted that “in short time [Stivetts] was acknowledged as one of the greatest pitchers in the league,” which led to Clarkson’s release.14 Stivetts’ season reads like a highlight reel. One day after playing in the outfield and belting a game-winning home run in the 12th inning of a scoreless game against the Brooklyn Grooms,15 Stivetts took the mound against them on August 6 and tossed the first no-hitter in Beaneaters history. In what was described by the Brooklyn Daily News as the Grooms’ “Waterloo defeat” in front of more than 7,000 spectators in Eastern Park in Brooklyn, Stivetts fanned six and walked five, and also scored twice in the 11-0 victory.16 Stivetts started and won both games of a doubleheader against the Louisville Colonels on September 5, yielding just three runs. In the second game of a season-concluding doubleheader against the Washington Senators on October 15, Stivetts fired a no-hitter that was called after five innings so that the Beaneaters could catch a train from the nation’s capital to Cleveland.17 Stivetts (35-16) matched Nichols for the club lead in victories and tied for third most in the NL, completed 45 of 48 starts, logged 415⅔ innings, and fanned (180) just a few more than he walked (171). He also batted .296 and played in the outfield in 18 games.

Because of the NL-AA merger, league directors had established an experimental split-season format for the 1892 season and tentatively planned for a best-of-nine championship series. The plan worked perfectly as the Beaneaters won the first half and the Cleveland Spiders the second, setting the stage for the first-ever NL championship series, which commenced on October 17 in Cleveland. The Spiders were favored even though they finished with a worse combined record than the Beaneaters (93-56 to 102-48). The first game became “one the most evenly contested games that ever took place on the diamond,” opined the Cincinnati Enquirer.18 In one of the greatest pitchers’ duels of the era, Stivetts and the 25-year-old Cy Young (in his third season, but already acknowledged as the best hurler in the league) battled for 11 scoreless innings, yielding just four and six hits respectively, before the game was called because of darkness and declared a tie. Two days later, the two hurlers squared off again, in Cleveland for Game Three, with Stivetts emerging victorious, 3-2. A rematch was scheduled for Game Five, on October 22 in Boston, but when Young complained of a sore arm, former Beaneater John Clarkson took the mound. The Spiders scored six unearned runs in the second inning, but Stivetts, gushed one reporter, “put on extra speed” thereafter while the Beaneaters whacked Clarkson to win, 12-7.19 Kid Nichols beat Young in Game Six to give the Beaneaters the championship, winning five games and tying one. Stivetts’ performance on the national stage secured his reputation: In 29 innings he yielded three earned runs, whiffed 17, and walked only seven. Despite the success of the series and the national excitement it generated, it was abolished after one season.

One of the most debated topics of the Hot Stove season was a major new rule instituted to increase scoring. The pitcher’s box was replaced by a rubber plate, increasing the distance to home plate from 55½ feet (rear line of box) to 60 feet 6 inches on a flat surface. Sportswriters, players, and fans found no consensus regarding the effect the change would have on speedballers like Amos Rusie and Stivetts. Sporting Life opined that the new distance would make Stivetts’ “drop ball more effective.”20 Without an adequate way to measure the speed of the ball, some thought hard throwers would be faster and those who struggled with control could become more dangerous. “I’m too young to die,” quipped John Montgomery Ward about his prospects facing Rusie and Stivetts.21

The change in pitching distance had a dramatic effect on baseball in 1893. Scoring increased from 10.2 total runs per game to 13.2; batting averages improved from .245 to .280; and slugging percentage increased by 51 points to .379. While skipper Frank Selee piloted the Beaneaters to their third straight championship, Stivetts was described in Sporting Life as “not pitching ball as he did last season and is surely not in good form.”22 Like all moundsmen, Stivetts had to adjust to the new distance to the plate; however, several additional factors played a role in his reduced numbers (20-12, 4.41 ERA, and 14 fewer starts than a year earlier). Boston sportswriter J.C. Morse wrote that Stivetts “pitched a good part of the time as if there were something the matter with his arm”;23 and Sporting Life reported in May that Stivetts’ “arm has not the movement characteristic of him and he has complained of arm pain.”24 He also battled with teammates, most notably star outfielder Hugh Duffy, who led the circuit in batting (.363). Their relationship was so toxic that Sporting Life noted that “it would seem to be in the best interest of harmony to let one of them go.”25 Both were still on the team the next season. Stivetts followed his own rules, such as going AWOL when the club was in Philadelphia in the early part of the season. Without permission he abandoned the club, for the second straight year, to visit his family in Ashland and drew criticism for not showing up for a game he was scheduled to pitch.26 That wasn’t the only time Selee had to find an emergency starter to replace Stivetts. On the club’s season-ending 18-game road swing, Stivetts reportedly showed up in Cincinnati so intoxicated that he couldn’t pitch. “[N]o doubt Stivetts indulgence in liquor has lessened his effect this season,” declared sportswriter O. P. Caylor.27

Still considered among the fastest throwers in the league, Stivetts no longer piled up the strikeouts from the new distance to the plate. After averaging 218 punchouts per season leading up to the change, he averaged 80 in the next four seasons (1893-1896). On the positive side, he developed better control of his heater and curveball, and his walks per nine innings decreased each season from a high of 4.7 in 1891 to a better-than-league-average 2.7 in 1896. He had a peculiar delivery that disrupted the batter’s timing. “[He] shakes his foot at the batter and his head at the second baseman just before delivering the ball,” read one description.28 The delivery was also called “erratic … requiring an artist to hold him.”29

Early in the 1894 season, Stivetts was on the hot seat in more than one way. On May 15 a fire erupted in the wooden grandstand at the Beaneaters’ home ballpark, the South End Grounds. As Terry Gottschall explained, the nine-alarm blaze swept through the ballpark and ultimately burned 12 acres and destroyed at least 200 buildings.30 Stivetts, who had had training as a fireman, a lifesaving ability when working in coal mines, apparently rescued a disoriented elderly man in a building next to the ballpark by braving the flames and extracting him from the second story.31 Stivetts, however, couldn’t save himself from a poor start, further exacerbating his strained relationship with club management, which according to the Boston Herald threatened to suspend him.32 On June 8, almost seven weeks into the season, Stivetts finally won his second game, but if anything, the burly hurler was streaky.33 Eight consecutive losses were followed by 11 straight victories.34 Tragedy struck the Stivetts family in August, when his 60-year-old father was crushed to death in a coal-mine accident.35 Stivetts ended his season for the third-place Beaneaters by defeating the Pirates 8-1 in Pittsburgh and collecting four hits.36 His 26 wins tied three others (including Cy Young) for fifth most in the league; he completed 30 of 39 starts and logged 338 innings. He yielded a league-most 27 round-trippers, the second of three times (1890 and 1896) he held that dubious distinction. While scoring increased to almost 14.8 total runs per game, Stivetts batted .328 (the team collectively hit .331, which ranked just third in the league) and slugged .533.

Dissension among Beaneaters players was palpable as the 1895 season commenced. Tensions erupted during spring training, when veteran Tommy McCarthy served as a special correspondent to a Boston newspaper.37 Some of his more seasoned teammates felt insulted by the way he portrayed them in the press, and animosity grew. Two cliques formed: close friends McCarthy and Duffy on one side, and Stivetts and team captain Billy Nash on the other. The situation came to a head on May 16 in Louisville. In the crowded hotel restaurant, where players and other guests suppered, McCarthy punched the seated Stivetts, his former Browns teammate, causing a “disgraceful affair.”38 Notwithstanding that sucker punch, Stivetts didn’t seem himself in 1895, thought Hub sportswriter J.C. Morse.39 The hurler was beset by a series of maladies: a “small tumor” removed from his left eye (probably a cyst),40 an injured arm from an exhibition game,41 and finally malaria.42 It was no surprise that the Beaneaters dropped to sixth place. Stivetts was still capable of “phenomenal speed” (such as in his two-hitter versus Rusie and the Giants on April 24);43 however, he split his 34 decisions and logged 291 innings.

In 1896 Stivetts had a season commensurate with his previous three on the mound, going 22-14 and logging 329 innings as the Beaneaters finished in fourth place. Noteworthy was his production with the bat. He had often claimed that he enjoyed hitting more than pitching and voiced his frustration with his career lows in at-bats (158) and appearances as a position player (7) in 1895. Skipper Selee inserted the now 28-year-old into the field 18 times and the strategy paid dividends. Stivetts batted .347 (in 222 at-bats), trailing only future Hall of Famer Billy Hamilton, acquired in the offseason from the Philadelphia Phillies for Nash; and posted the highest slugging percentage on the team (.482). On June 12 Stivetts proved to be a double threat, going the distance in a 15-3 victory over the Reds in the Queen City, walloping two home runs among his four hits, and scoring four times.44

Given Stivetts’ success at the plate, local and national media suggested that he’d be more valuable as a hitter. Selee, perhaps hedging his bets in case Stivetts’ right arm failed, worked the hurler out at first and in the outfield during spring training, anticipating that the burly Pennsylvanian would play more in the field. In April Stivetts suffered a severely torn ligament in his right forearm.45 That injury eventually ended his career as a twirler; however, it also enabled him to play more regularly in the field once he healed. After a brief demotion to Fall River (Massachusetts) in the New England League in mid-June, Stivetts pitched sparingly as the club’s fourth starter, posting an 11-4 record and logging 129⅓ innings. Led by Kid Nichols, whose league-best 31 victories matched his average since debuting in 1892, Fred Klobedanz (26-7), and Ted Lewis (21-12), the Beaneaters emerged victorious in an exciting pennant chase with the Baltimore Orioles, capturing the flag by two games and setting a franchise record-high winning percentage (.705). Stivetts proved to be a valuable contributor. Making a career-high 29 starts as a flychaser, plus two at both first and second base, Stivetts led the team in batting (.367) and slugging (.533) in 199 at-bats.

With the emergence of Klobedanz and Lewis, Stivetts was converted to a full-time fielder in 1898; however, he lacked a natural position. Not fast enough to replace outfielders Duffy, Hamilton, or Chick Stahl, each of whom batted at least .340 in 1897, and not adroit enough with the glove to be a full-time infielder, Stivetts took on the role as a super-utility player, making appearances in the outfield and at first, second, and shortstop. His average dipped to .252, the result of a series of hand injuries. With rumors of his impending trade to the St. Louis Browns, Stivetts injured his thumb in late July, prematurely ending his season.46 He left the club and returned home to Ashland to recuperate. When he received word that he had been traded to the Browns for pitcher Kid Carsey, Stivetts refused to return to the club and its owner von der Ahe, whose stadium had burned down in April.47 The trade nullified, Stivetts was eventually sold outright to the Browns in mid-August.

Stivetts had a change of heart about the Browns in the offseason when Frank and Stanley Robison purchased the club, on the verge of financial collapse, from von der Ahe. Stivetts never donned the uniform of the Perfectos, the club’s new name; rather, he was transferred to the Cleveland Spiders, also owned by the Robison brothers. In an obvious conflict of interest, the Robisons transferred the Perfectos’ least productive players to the Spiders, which they ran like a circus show, side-project (they finished with the worst record in major-league history, 20-134). Stivetts lost all four of his decisions, batted .205, and was given his outright release on June 17.

So ended Stivetts’ professional baseball career. He returned to his family in Ashland, where lived for the remainder of his life. He had married local Margaret Ann Thomas on June 30, 1886, and together they raised six children (five daughters and a son) born between 1889 and 1907. Like his father, Happy Jack ended up in a coal mine, but in a less dangerous role as a carpenter. He had also worked delivering beer during his playing days. Just 31 years old, Stivetts wasn’t finished with baseball. For the next decade, he played semipro ball for a number of local teams, flashing the heat that propelled him to the majors where he had posted a 203-132 slate and logged 2,887⅔ innings. When Ashland’s most famous citizen could no longer pitch, he managed and umpired in local leagues.

Jack Stivetts died on April 18, 1930, from a heart attack after falling down a stairwell.48 He was 62 years old. Like his parents, he was buried in Ashland’s Brock Cemetery.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also accessed Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, SABR.org, Sporting Life via the LA84 Foundation, The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record, and the player’s file from the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York.

Notes

1 Sporting Life, July 21, 1894: 2.

2 Information about the Stivetts family is from US Census reports via Ancestry.com

3 Robert L. Tiemann, “John Elmer Stivetts,” Nineteenth Century Stars, Robert L. Tiemann, Joseph Overfield, L. Robert Davids, Richard Puff, eds. (Phoenix: Society for American Baseball Research, 2012.)

4 “Base Ball Topics,” Philipsburg (Montana) Mail, December 15, 1899: 2; and “Stivetts Hailed as ‘Peer of Living Pitches’ by Baseball World of ’89.” [untitled and undated article from players’ file, Baseball Hall of Fame].

5 Sporting Life, July 1, 1893: 3.

6 Sporting Life, July 10, 1893: 3.

7 The official name was the Players’ National League of Professional Base Ball Players.

8 Joe Pritchard, “St. Louis Stiftings,” Sporting Life, May 3, 1890: 9.

9 Sporting Life, May 8, 1890: 13.

10 Sporting Life, June 14, 1890: 13

11 “He Stored Them,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 29, 1891: 2.

12 “Stivetts Suspended,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 20, 1891: 8.

13 “O’Neil Answered,” Sporting Life, December 5, 1891: 10.

14 Sporting Life, October 29, 1892: 9.

15 “Umpire Lynch Did It,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 6, 1892: 3. 5

16 “Not a Hit off Stivetts,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 7, 1892: 8.

17 Sporting Life, October 22, 1892:4.

18 “Superb World’s Championship Battle,” Cincinnati Enquirer, October 18, 1892: 2.

19 “Out In Front. Cleveland Gets The Best of It,” Cincinnati Enquirer, October 22, 1892: 6.

20 “Lucid Interval,” Sporting Life, December 31, 1892: 3.

21 “We Plead Guilty,” Sporting Life, November 20, 1892: 9.

22 Sporting Life, May 18, 1893: 2.

23 J. C. Morse, “Hub Happenings,” Sporting Life, March 31, 1894: 5. [Date is partially missing from the paper].

24 Sporting Life, May 18, 1893: 2.

25 “Cincinnati Chips,” Sporting Life, December 30, 1893: 2.

26 “A Timely Suggestion for Boston,” Sporting Life, May 6, 1893: 2.

27 O. P. Caylor, “The Pennant Winner,” Akron Daily Democrat, October 7, 1893: 5.

28 Sporting Life, September 16, 1893: 2.

29 J. C. Morse, “Hub Happenings,” Sporting Life, January 20, 1895: 5.

30 Terry Gottschall, “May 15, 1894: ‘It was a Hot Game, Sure Enough’,” SABR Games Project. https://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/may-15-1894-it-was-hot-game-sure-enough

31 “Stivetts A Hero,” Sporting Life, October 20, 1894: 4.

32 Boston Herald as quoted in Sporting Life, June 2, 1894: 1.

33 Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), June 9, 1894: 11.

34 Tiemann.

35 “Stivetts’ Father Killed,” Evening Herald (Shenandoah, Pennsylvania), August 24, 1894: 1.

36 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 28, 1894: 7.

37 “Internal Dissensions,” Sporting Life, March 28, 1896: 2.

38 “’Striking’ lack of Harmony,” Sporting Life, May 25, 1895: 3.

39 J. C. Morse, “Hub Happenings,” Sporting Life, August 31, 1895: 7.

40 Sporting Life, June 8, 1895: 4.

41 J. C. Morse, “Hub Happenings, Sporting Life, July 27, 1895: 6.

42 J. C. Morse, “Hub Happenings,” Sporting Life, August 31, 1895: 7.

43 Wm. F. H. Koelsch, “New York News,” Sporting Life, May 4, 1895: 3.

44 Pittsburgh Daily Post, June 13, 1896: 6.

45 J. C. Morse, “Hub Happenings,” Sporting Life, May 1, 1897: 1.

46 J. C. Morse, “Hub Happenings,” Sporting Life, August 6, 1898: 19.

47 “Jack Stivetts Sold,” Buffalo Commercial, August 20, 1898: 4.

48 Bill Lee, The Baseball Necrology (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2009), 382.

Full Name

John Elmer Stivetts

Born

March 31, 1868 at Ashland, PA (USA)

Died

April 18, 1930 at Ashland, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.