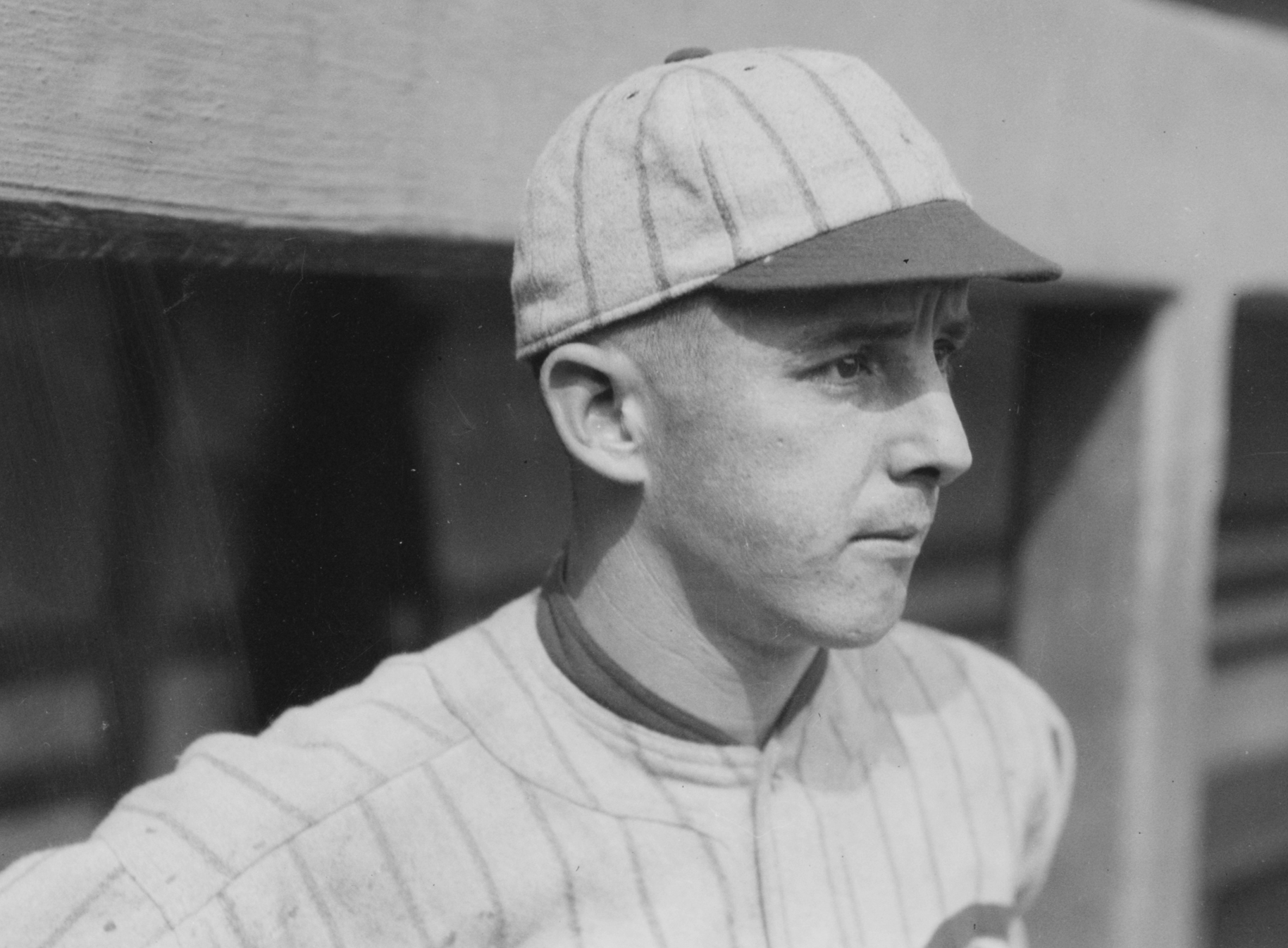

Lefty Williams

In 1915, America’s leading syndicated sportswriter, Hugh Fullerton, published a forgettable baseball novel in which a star left-handed pitcher named Williams is bribed and threatened by gamblers to lose the pennant for his team.1

In 1915, America’s leading syndicated sportswriter, Hugh Fullerton, published a forgettable baseball novel in which a star left-handed pitcher named Williams is bribed and threatened by gamblers to lose the pennant for his team.1

Fullerton, who dedicated the novel to his friend and mentor, Chicago White Sox owner Charles Comiskey, had been writing about the menace of gambling in professional baseball for more than a decade. Little did he know how prescient his story would turn out to be.

Just a few years later, Fullerton had a front-row seat in the press box as one of the Chicago White Sox’ star pitchers, Claude “Lefty” Williams, became embroiled in the most devastating game-fixing scandal baseball had ever seen, the throwing of the 1919 World Series. Williams and seven of his teammates were expelled from Organized Baseball for their roles in losing the tainted World Series to the Cincinnati Reds. Williams set a World Series record with three losses all by himself, including a disastrous one-inning appearance in the Series’ final game that left no doubt as to his involvement in the Black Sox Scandal.

Considered one of the most promising left-handers in baseball, Williams recorded back-to-back 20-win seasons with the White Sox in 1919 and ’20, and he was being groomed to replace Eddie Cicotte as the staff ace. But he threw away his career for a $5,000 reward from gamblers, ending the White Sox’ potential championship dynasty before it ever really began. More than any other player involved in the 1919 World Series fix, Williams struggled to make peace with his fateful decision to accept the bribe; only with the unconditional support of his strong-willed wife, Lyria, did he turn around his life after he was kicked out of baseball prematurely.

- Learn more: Click here to view SABR’s Eight Myths Out project on common misconceptions about the Black Sox Scandal

Claude Preston Williams was born on March 9, 1893, in Aurora, Missouri, the second child in a rural farming family that originally hailed from Crawford County, Arkansas. When Claude was about 8 years old, his father, William H. Williams, died and his mother, Mary “Addie” Seratt, soon married Robert A. Grimes, a railroad worker for the St. Louis-San Francisco Railway in nearby Springfield.2 Claude and his older brother, Jessie, welcomed a half-brother, Lawrence, in 1904.3

Claude Williams attended one year of high school4 before taking a job in town as a grocery clerk. Like many boys his age, he was more interested in athletics than academics. In 1910 he paid 50 cents to join the O’Leary’s Athletic Club gymnasium with his friend, Luther McCarty, a promising boxer.5 Williams was “fairly handy with his dukes” and sparred regularly at the gym, but he rebuffed his friends’ pleas to take boxing more seriously. His future was in baseball.6

In 1911 the 18-year-old Williams signed a contract to play with Springfield in the independent Kansas-Missouri League.7 Despite a “peculiar” motion, in which he released the ball low from a side-arm position but kept his torso upright,8 his strong pitching caught the attention of the Nashville Vols of the Southern Association. But “wildness kept him from making good” in a tryout and the Vols farmed him out to Morristown, Tennessee, of the Appalachian League for the 1912 season.9

Williams, who filled out to be a slim 5-feet-9 and 160 pounds, dominated the Appalachian League in 1912, finishing 18-11 with a 1.92 ERA for Morristown. His control also improved greatly, as he walked just 46 batters in 253 innings pitched. In August Nashville sold his contract to the Brooklyn Dodgers, but manager Bill Dahlen decided not to recall Williams and several other prospects during the season’s final month. Before the 1913 season began, Williams was optioned back to Nashville.10

Williams’s second stint in Tennessee was much more productive. He was the youngest member on the Vols roster at age 20, called “The Kid” by fans in Nashville that year.11 He led the Vols in wins (18), ERA (2.30), and WHIP (1.078.) In August Williams was sold to the Detroit Tigers for $3,500.12 This time, he was sent up to the majors.

Ty Cobb helped Lefty Williams win his major-league debut for the Tigers, on September 17, 1913. In the second game of a doubleheader at Washington, Cobb hit a first-inning grand slam and Williams scattered eight hits in a 4-2 complete-game victory.13 In his next start, against the Philadelphia A’s, he didn’t fare so well — he allowed ten hits and ten runs in a single inning against the eventual World Series champs.14 Williams made three other appearances for Detroit, but lost two of them.

The Tigers kept Williams around to begin the 1914 season, but he made just one start — another blowout loss to the A’s on May 22 in which future Hall of Fame outfielder Harry Heilmann made three errors in the first inning. Two weeks later, Detroit sold a frustrated Williams to the Sacramento Wolves of the Pacific Coast League. His PCL debut, on June 7, was a sign of things to come as he struck out 12 Portland Beavers batters, setting a new career high. Despite joining the Wolves in June, two months after the PCL season began, Williams finished fifth in the league in strikeouts with 171.15

Williams’s season of turmoil continued all summer as he suffered a string of hard-luck losses, finishing with just a 13-20 record. The Sacramento Wolves were also in financial turmoil; in September, they abandoned California’s capital city and played the rest of their home games in San Francisco’s Mission district.16

In 1915 the financially strapped Wolves transferred operations to Utah and found a permanent home as the Salt Lake Bees. There, Lefty Williams, now 22, found his greatest success on the field and enduring love off the field in Lyria Leila Wilson, the charismatic, independent daughter of Mormon pioneers.

Lyria, the youngest of 15 children to Calvin and Emeline (Miller) Wilson, was three years older than Lefty and had been living on her own since at least 1909.17 Her grandfather, Whitford Gill Wilson, had moved his family to the Mormon-established town of Nauvoo, Illinois, in the late 1830s before migrating to Ogden, Utah, as part of the forced exodus of Mormon settlers from the Midwest.18

By 1915, Lyria was working as a waitress at a Salt Lake City hotel frequented by Coast League ballplayers. No player that year was more dominant than Lefty Williams. Before the season, the Salt Lake Telegram reported, “Everybody on the coast predicts a great year for [Williams.] In fact, some of them feel that he will be a Coast League sensation.”19 After several outstanding performances in California during the winter-league season, Williams turned heads in a late February exhibition game against the Chicago White Sox in San Jose.20

Perhaps the excitement of his courtship with Lyria, or the close rapport he established with Bees catcher Byrd Lynn, helped raise Lefty’s game to new heights. Whatever the reason, Williams far outclassed the rest of the PCL in 1915, finishing with a stellar 33-12 record, a 2.84 ERA, 36 complete games, and a league-leading 294 strikeouts in 418⅔ innings pitched for Salt Lake City. The league’s runner-up in strikeouts, Bill Prough of Oakland, finished nearly 100 behind Williams.21 Williams struck out 12 San Francisco Seals on May 2 and set a season high by fanning 13 Vernon Tigers on September 8.22 It was one of the best PCL pitching performances of the decade, earning Williams a call-up to the Chicago White Sox in 1916.

Williams was one of five Coast League recruits purchased by Charles Comiskey’s White Sox that offseason, including his Salt Lake batterymate Byrd Lynn. The 23-year-old left-hander made the White Sox roster out of spring training and quickly established himself as one of the top strikeout pitchers in the American League in 1916.

The rookie left-hander saved his best performances for the stretch run, compiling a 5-1 record in September with four complete games in seven starts. But the defending champion Boston Red Sox outlasted the young White Sox and won the pennant by two games over Chicago. Williams finished 13-7 with a 2.89 ERA in 224⅓ innings, and his rate of 5.5 strikeouts per nine innings was second-best in the American League to only Hall of Famer Walter Johnson.23

Off the field, Lefty and Lyria decided that a long-distance relationship wasn’t suitable for them. So a few weeks into the season, Lyria packed up and traveled by train from Salt Lake City to Chicago, where the couple was married on June 6, 1916. No one on the White Sox except catcher Byrd Lynn, Lefty’s roommate at the Warner Hotel, knew about the nuptials before they took place.24

Perhaps happiness at home helped lead to a spectacular start for Williams at the ballpark in 1917. Despite not lasting past the first inning on Opening Day against the St. Louis Browns, Williams won his first nine decisions and didn’t suffer his first loss until June 28 in a relief appearance against the Detroit Tigers.25 By then the White Sox were in first place with the best-scoring offense and stingiest pitching in the American League.

But Williams’s stellar won-loss record (he finished 17-8) was mostly the product of strong run support, and his frequent bouts of wildness caused manager Pants Rowland to skip his turn in the rotation sometimes.26 His ERA hovered over 3.00 for most of the season, above the league average, and his 85 strikeouts were far off the pace he had set as a rookie.

In the World Series against the New York Giants, the struggling Williams was passed over for a Game Five start in favor of Reb Russell, who didn’t record a single out before he was replaced by Eddie Cicotte in the first inning. With the White Sox down 4-2, Williams relieved Cicotte in the seventh, allowing one run and striking out three in his only inning of the Series. The White Sox rallied to win, 8-5. Two days later, Williams watched from the dugout at the Polo Grounds as Chicago clinched its second World Series championship.

The White Sox’ championship lineup remained intact to start the 1918 season under manager Pants Rowland. But as local draft boards all over the United States began selecting able-bodied adult men for military service in World War I, the White Sox were depleted by the sudden loss of star outfielder Shoeless Joe Jackson in mid-May. With enlistment in the armed forces a near-certainty due to a change in his draft status, Jackson chose to take a war-essential job with the Harlan & Hollingsworth shipbuilding company in Wilmington, Delaware.27

As The Sporting News later observed with tongue only partially in cheek, “Where Jackson goes, Williams follows.”28 Williams, who like Jackson was married and at age 25 was five years younger, was considered exempt from active military service (since his wife, Lyria, depended on his income).29 But all professional ballplayers knew they would soon have to find another line of work, as the US government issued a “work or fight” order in July that prematurely ended the 1918 baseball season.30

Four weeks after Jackson went to Delaware, Williams and catcher Byrd Lynn abruptly left the White Sox and joined Jackson at the Harlan & Hollingsworth plant. Owner Charles Comiskey responded by suspending the three players indefinitely and stripping them of their uniforms. “I don’t consider them fit to play on my ballclub,” he said.31 Comiskey also refused to issue Williams his final paycheck, a grand total of $183.16 for the 11 days he spent with the team in June.32

In the typical wartime frenzy of patriotism, many baseball fans and members of the press took Comiskey’s side; the White Sox players were considered to be “slackers” and “cowards” for avoiding military service.33 “Nothing was too mean to call them,” said one American League ballplayer.34

Williams spent the duration of the war pitching for Harlan’s company team in the prestigious Delaware River Shipbuilding League, one of many industrial leagues that employed major-league players. In September Williams pitched a 4-0 shutout and Jackson hit two home runs to help Harlan clinch the championship of Atlantic Coast shipyards against Standard Shipbuilding of Staten Island, New York, in a game played before 4,000 fans at the Baker Bowl, the Philadelphia Phillies’ home ballpark.35

Despite Comiskey’s bluster in the press, he allowed all of his “unpatriotic” shipyard players to return to the White Sox in 1919 under new manager Kid Gleason.36 Williams signed a contract for $2,625, with a $375 bonus if he won 15 games and an additional $500 bonus if he won 20 games.37 With teammate Red Faber under the weather due to influenza, Williams was counted on to pick up the slack and the little left-hander responded with a stellar season.

Williams led the American League in 1919 by making 40 starts, including ten alone in July when the White Sox surged to the top of the standings for good. He also ranked second with 27 complete games and five shutouts, and third with 125 strikeouts. In September, he tossed two shutouts to finish 23-11 with a 2.64 ERA as Chicago won its second pennant in three seasons.

Williams also gained a reputation as a great control pitcher, ranking fourth in the AL in walks per nine innings. Before the World Series, manager Gleason exclaimed in a syndicated column, “It isn’t often that a batter gets a ball in the groove when Williams is pitching. He’s always on the edge of the plate … where they’ve got to swing and where they can’t often get a good hold of the ball.”38

But Williams didn’t intend to live up to his reputation in the 1919 World Series. On the White Sox’ final Eastern road trip in late September, he was approached by first baseman Chick Gandil outside the Ansonia Hotel in New York. Gandil said a group of teammates were planning to throw the World Series to the Cincinnati Reds. Lefty agreed to participate, for a promised payoff of $10,000. He told Gandil that “anything they did would be agreeable to me, if it was going to happen anyway. … I had no money and I might as well get what I could.”39

Although most of the White Sox players were well paid compared with their peers,40 Williams’s $500-a-month salary was half of what his good friend Joe Jackson was making. Williams was also still bitter that Comiskey hadn’t paid him the salary he felt he was owed after he went to work in the shipyards the previous June.41

Picked to start Game Two of the World Series, Williams immediately raised suspicions with an uncharacteristically wild performance. After facing the minimum nine batters through three scoreless innings, he abruptly lost his command in the fourth inning. He walked three Reds batters and allowed an RBI single to Edd Roush and a two-run triple to light-hitting Larry Kopf. Williams allowed only four hits but walked six (tying a career high) in the 4-2 loss.

Irving Sanborn of the Chicago Tribune wrote that Williams’s pitching was “almost criminally wild,”42 although umpire Billy Evans, who was behind home plate that day, later said he “regarded the loss of that game at the time as one of the hardest bits of luck I ever saw.”43 All of the fourth-inning walks were on full counts44 and “not one of them was over six inches inside or outside,” Evans recalled. But White Sox catcher Ray Schalk suspected something was off. He reportedly confronted Williams after the game about his lack of control, and may have even physically assaulted him.45 It was a sign of the rising tensions in the White Sox clubhouse.

Williams expected to get paid by the gamblers for his losing effort, but when the money didn’t show up after Game Two or Three, he began to suspect a double-cross. Finally, after Game Four — with the White Sox now down three games to one — Williams collected $10,000 from Chick Gandil, who instructed him to give half of the cash to Joe Jackson.46 Lefty gave the money to Jackson in a dirty envelope, sealing both of their fates. Lefty’s wife, Lyria, was furious when she found out. “You have done it,” she told him after seeing the cash. “What can I say now? Let it go and just get the best of it.”47

Flush with cash, Williams pitched poorly enough to earn his payoff in his next start, in Game Five against the Reds. Once again one disastrous inning was his downfall. After allowing just one hit through five innings, Williams gave up four runs in the sixth. Cincinnati’s rally began with a double by the pitcher, Hod Eller. The White Sox lost, 5-0. Williams later admitted that he was nervous because the fix was on his mind. “I was sorry,” he said. “I wanted to be out of it and not mixed up in it at all.”48

If the World Series had been played under its traditional best-of-seven format, the Reds would have clinched the championship after Williams’s loss in Game Five. But baseball owners had expanded the fall classic to a best-of-nine series49 and Williams took the mound for one more start after the resurgent White Sox, on the verge of elimination, won Games Six and Seven. By then the fixers hadn’t received any more of their promised payoff from gamblers and were seemingly playing to win. Before Game Eight, Williams told Joe Jackson on the way to Comiskey Park, “If we have been double-crossed, I am going to pitch to win this game if I can possibly win it.”50

Instead, Williams had the worst performance of his life. He lasted all of five batters in Game Eight as the Reds battered him for four hits and four runs before manager Kid Gleason yanked him in the first inning. The White Sox were never in the game and the Reds won, 10-5, to clinch their first World Series championship.

It is widely believed that a threat was made against Williams’s life before the game, but the evidence to substantiate that claim is thin.51 Lyria Williams reportedly said years later that Lefty was fearful of retaliation if he didn’t lose Game Eight quickly and decisively.52 “It’ll be the biggest first inning you ever saw,” one gambler predicted to sportswriter Hugh Fullerton before the game, perhaps insinuating that Williams was warned to put the game out of reach before three outs were made.53 But Williams testified later that he pitched to win in Game Eight; he also told Cicotte during the Series “that he was out to win because he had been double-crossed.”54

Regardless of whether a real threat was made, Williams got the message all right. His 0-3 record in the World Series set a record that still stood as of 2024 and undoubtedly helped the gamblers turn a tidy profit betting on the Reds. Williams, like Joe Jackson, earned just $5,000 for throwing the Series — about $200 less than each player on the Reds received for actually winning the Series.55

Although owner Charles Comiskey, manager Kid Gleason and other team officials were aware of the fix, they were intent on sweeping it under the rug and keeping their championship team intact in 1920.56 The White Sox offered generous contracts to seven of the eight White Sox conspirators in the offseason. Williams signed for $6,000, more than he had received for fixing the World Series the previous fall.57

With a black cloud hanging over baseball because of the fix rumors, Williams had a turbulent season in 1920. His won-loss record was again superb at 22-14, and he finished second in the AL in games started (38) and strikeouts (128). But in the first year of the live-ball era, Williams’s longtime tendency to be a fly-ball pitcher caused him to lead the league in home runs allowed (15), and his 3.91 ERA was again above the league average.58

In September a grand jury was empaneled in Chicago to investigate gambling in baseball. The grand jury soon turned its focus to the 1919 World Series, and pressure mounted on the White Sox players to come clean. On September 28 pitcher Eddie Cicotte cracked first, testifying about his involvement in throwing the Series to the Reds and igniting a scandal that made headlines all across the country.

Later that afternoon, Joe Jackson followed Cicotte to the witness stand and told the grand jury that he had received $5,000 from Williams after Game Four.59 Once again, Williams found himself suspended by Charles Comiskey, along with the other seven White Sox players named as fixers: Cicotte, Jackson, Swede Risberg, Chick Gandil, Happy Felsch, Fred McMullin, and Buck Weaver.

The next day, September 29, Williams paid a visit to the office of Alfred Austrian, the White Sox’ team counsel, where he gave a sworn statement admitting his involvement in the World Series fix. He then went to the Cook County Criminal Court Building and testified in front of the grand jury, shedding new light on the multiple groups of gamblers involved in fixing the World Series.60 Williams’s testimony was the third and final confession that the grand jury heard. It was more than enough evidence to return indictments against all eight players, along with a handful of gamblers. The White Sox, without their suspended stars, played out the final weekend with a makeshift roster and finished in second place, two games behind the Cleveland Indians.

In the summer of 1921, Williams and his seven former teammates went on trial in Chicago for fixing the World Series. The proceedings were farcical from the start, characterized by an inept, clumsy prosecution and a star-struck jury. On the evening of August 2, the first verdict was announced: “We, the jury, find the defendant Claude Williams … not guilty.”61 A loud cheer broke out in the courtroom and jurors celebrated by asking for the players’ autographs.

But hours later, baseball’s new commissioner, Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, delivered a different verdict: The Black Sox were permanently banned from playing in Organized Baseball. At age 27, Lefty Williams’s major-league career was over just as he was coming into his prime. Nearly a century later, no other American League pitcher had recorded more wins in his final active season than Williams’s 22 in 1920.62 In seven seasons, he finished with 82 wins against just 48 defeats, a .631 winning percentage that ranked in the top 25 all-time among American League pitchers in the 20th century (with a minimum 100 decisions).63

Life after baseball was a constant struggle for Lefty Williams. Like many players of his era, he had few other marketable skills outside of his ability to play baseball. After struggling to run a pool hall on Chicago’s South Side that Joe Jackson sold to him for $1, Williams took odd jobs as a painter, a department store floorman, and a tile-fitter to make ends meet.64 He began drinking more and his marriage suffered. In 1923 he reportedly suffered a serious bout of pneumonia that landed him in the hospital and nearly killed him.65 The following year, with Lefty still drinking heavily, Lyria kicked him out of the house and the couple separated.66 So Lefty turned back to baseball, the only job he knew.

After the Black Sox were banned in 1921, they mostly went their separate ways. But none of them stayed away from a baseball field for long. And in the 1920s, semipro baseball could be a lucrative career for a former professional of Williams’s caliber. In the summer of 1922, he joined Swede Risberg, Buck Weaver, and Happy Felsch on a team promoted as the “Ex-Major League Stars,” which toured the Midwest playing town teams in Illinois, Wisconsin, and Minnesota. Fans grew disillusioned by their lackluster play, however, and the “Ex-Stars” earned just a few hundred dollars for their efforts.67

Williams continued pitching for hire and, in 1926, after his separation from Lyria, Buck Weaver persuaded him to move west for the summer. Weaver, Chick Gandil, and the notorious game-fixer Hal Chase were members of an outlaw league near the US-Mexico border called the Copper League. The Copper League could employ the Black Sox players and others who had been banned by Judge Landis because it was unaffiliated with Organized Baseball. Weaver, the popular manager of the Douglas (Arizona) Blues, signed Williams to a salary of about $160 per month.68

Money woes plagued Douglas throughout its tenure in the Copper League and by mid-June, Williams had jumped to the Fort Bayard (New Mexico) Veterans for more money and a steady job in the motor-vehicle division of the military hospital there.69 With Fort Bayard, Williams and Jimmy O’Connell — a former New York Giants outfielder who was kicked out of baseball for allegedly offering a bribe to an opponent70 — quickly became the cream of the outlaw crop. Williams threw the season’s only no-hitter, on August 8 against Buck Weaver’s Douglas Blues.71 O’Connell hit .546 and led the Copper League in home runs as the Veterans won the championship. After the season, Williams joined an all-star team that toured Mexico City, Chihuahua, and other Mexican cities in the fall.

Williams stayed in Fort Bayard for the winter, working contentedly at the hospital and spending most days drinking and playing cards.72 In 1927 he and O’Connell led the Veterans to first place once again and the powerhouse team became known locally as the “Bayard Express.”73 But they lost the championship series to the Chick Gandil-managed Chino Twins, from nearby Santa Rita, New Mexico.74 Williams’s time in rural New Mexico was the last significant baseball experience of his life, a far cry from the bright lights of the major leagues he had enjoyed just seven years earlier. The Copper League, which was hanging on by a thread financially, disbanded after the 1927 season when Judge Landis promised to give minor-league teams to the league’s cities if they stopped using banned players.

By the early 1930s, Lefty Williams was back in Chicago, living in a small basement apartment in Rogers Park on the North Side of town, and he had begun patching up his relationship with Lyria, who continued to work as a cashier.75 They stayed in Illinois until 1937, when Lyria’s increasing involvement with the Christian Science church compelled them to move west again, this time together. They were among the more than 1 million Americans who migrated to California, the land of opportunity, during the Great Depression.76

The Williamses settled first in Burbank, where Lyria’s brother, Lawrence Wilson, likely helped Lefty get a job as a truck driver.77 Lyria, no longer working outside the home, put her boundless mental energy to other uses. Over the years she developed a reputation as a civic gadfly and a community activist; she often appeared at city council meetings questioning zoning changes, street pavings, and other neighborhood proposals.78 Lefty and Lyria also maintained their close friendship with Joe and Katie Jackson over the years and visited each other occasionally. When Shoeless Joe died in 1951, the Williamses wired their condolences to his widow.79

During World War II, Lefty and Lyria relocated for a few years — although it’s unclear exactly why — to Pearblossom, a remote area in the Antelope Valley north of Los Angeles.80 Lefty worked as a carpenter and he also tried his hand at gardening at their modest property off Pearblossom Highway. They lived a few miles from the ranch of eccentric author Aldous Huxley, who had moved to California’s High Desert for the cleaner air.81 After the war ended, the Williamses moved back to the San Fernando Valley, where they bought a house in Northridge.82

In 1954 Lefty made the final move of his nomadic life, about 80 miles south to Laguna Beach, where he opened nursery business.83 He and Lyria bought a hillside beach cottage in the historic Coast Royal neighborhood of South Laguna, with a view of the Pacific Ocean — and, on clear days, Catalina Island — from their front window.84

Lefty’s last years were plagued by the effects of Hodgkin’s disease, and by 1959, when the White Sox won their first pennant since the Black Sox Scandal, their former star pitcher was on his deathbed. A Santa Ana Register columnist wrote, “Under normal circumstances, this would have been a happy year for Williams. He would have been sounded out for stories of the old days, interviewed, maybe given a chance to throw out a first ball at the World Series. Instead he was tired and aging and ill and sick at heart. … I should say that if ever men paid for their sins, these did.”85

At age 66, Claude “Lefty” Williams died at home on November 4, 1959, less than a month after the White Sox lost to the Los Angeles Dodgers in the World Series. A Christian Science funeral was held and his ashes were interred in an unmarked location at Melrose Abbey Memorial Park in Anaheim, California.86

Like most of his old White Sox teammates, Williams rarely spoke publicly about the Black Sox Scandal or his role in the World Series fix. Always a quiet, thoughtful type, he and Lyria stayed out of the spotlight and didn’t respond to any known interview requests.87 Eight Men Out author Eliot Asinof suggested that the shame of the scandal left a lasting impression. “There’s a lingering impact on all of baseball,” Asinof said decades later. “You don’t talk about this thing. … Even sympathetic ballplayers who did not involve themselves in the fix refused to talk.”88

But as one childhood friend reminisced after Williams’s death, “he couldn’t help but have done a lot of reflecting” over the years.89 Lefty Williams might have been remembered as one of the top left-handed pitchers in the American League during the 1920s — if not for the scandal. He and future Hall of Famer Red Faber might have led a White Sox team that challenged the famous Murderers’ Row dynasty of Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and the New York Yankees. Instead, without their banished stars, the White Sox sank in the doldrums and didn’t win another World Series for the rest of the 20th century. Williams’s record of three losses in a single World Series, which still stood in 2024, might never be broken.90

Notes

1 Hugh S. Fullerton, Jimmy Kirkland and the Plot for a Pennant (Philadelphia: The John C. Winston Co., 1915).

2 1900-1910 United States censuses and Arkansas County Marriages Index, 1837-1957, accessed at Ancestry.com.

3 “The Frisco” was the major employer in the area; both Robert and Lawrence Grimes worked at the railroad’s Springfield operational center for many years. “The Frisco: A Look Back at the St. Louis-San Francisco Railway,” Springfield-Greene County Library District. Accessed online at http://thelibrary.org/lochist/frisco/about.cfm on October 9, 2013.

4 1940 United States census, accessed online at Ancestry.com. Contrary to most reports, the banned Black Sox ballplayers were more educated than they sometimes let on. Fred McMullin and Chick Gandil both told census takers in 1940 that they had attended four years of high school, while Buck Weaver said he had completed at least two years. Swede Risberg stayed in school through the eighth grade and pitched for his school’s baseball team. Eddie Cicotte and Happy Felsch both completed five or six years of grammar school. Only Joe Jackson was truly uneducated; the famously illiterate ballplayer dropped out after the third grade.

5 “Claude Williams and Lute McCarty Started Athletic Careers Together,” Gulfport Daily Herald, March 7, 1914.

6 “Luther McCarty,” BoxRec Boxing Encyclopedia. Accessed online at http://boxrec.com/en/boxer/39623 on March 3, 2019. McCarty made his pro debut in 1911 and quickly built a national reputation as the top “white hope” challenger to the black heavyweight champion Jack Johnson. But in May 1913, the 21-year-old McCarty collapsed during a fight in Calgary and died of a brain hemorrhage.

7 “Who’s Who in the World’s Series,” Salt Lake Telegram, October 1, 1917.

8 “American League News,” Sporting Life, July 8, 1916, 8. Video of Williams pitching from the 1919 World Series can also be found online at BlackBetsy.com.

9 Lefty Williams player file, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, New York; “Who’s Who in the World Series,” Salt Lake Telegram, October 1, 1917.

10 “Cubs Buy Recruit From Brooklyn,” Washington Post, August 22, 1912, 8; “Buy Players’ Releases,” New York Times, August 29, 1912, 7.

11 Nashville Banner, April 18, 1919.

12 Williams player file, Hall of Fame Library.

13 Stanley T. Milliken, “Tigers Win Two Games By Having Big Innings,” Washington Post, September 18, 1913, 8.

14 “Athletics Score 10 Runs in One Inning,” Hartford Courant, September 24, 1913, 16.

15 “Ed Klepfer Is Strikeout King,” Los Angeles Times, November 17, 1914.

16 “Strict Censorship On Coast’s Plans,” The Sporting News, October 1, 1914, 3.

17 1910 US census, accessed online at Ancestry.com.

18 Florence C. Youngberg, Conquerors of the West: Stalwart Mormon Pioneers (Salt Lake City: Agreka Books, 1999); Mormon Pioneer Overland Travel Database, accessed online at http://history.lds.org/overlandtravels on April 11, 2014.

19 “Blankenship Signs Southpaw Williams,” Salt Lake Telegram, February 17, 1915.

20 “Big Leaguers Beat Mormons,” The Oregonian, March 1, 1915.

21 “Claude Williams the Whole Show in League,” Los Angeles Times, October 28, 1915.

22 Ibid.; Salt Lake Telegram, September 9, 1915.

23 Baseball-Reference.com.

24 “Lefty Gets a June Bride,” Los Angeles Times, June 7, 1916; “Diamond Dust,” Salt Lake Telegram, June 7, 1916; Cook County Marriages Index, 1871-1920, accessed at Ancestry.com.

25 Baseball-Reference.com game logs.

26 Despite a reputation for good control, Williams in 1917 walked five batters in three different starts, and walked four batters apiece in six starts. All statistics are from Williams’s Baseball-Reference.com game logs.

27 “Sox Manager Sends Joe Jackson Away With Best Wishes,” Chicago Tribune, May 14, 1918, 15; “Comiskey Wipes 2 Shipbuilders Off Roster,” Chicago Tribune, June 12, 1918, 11. Jackson’s local draft board in Greenville, South Carolina, reclassified him as 1A, the most likely to be called up, despite the fact that he was married. Williams and most of the other married ballplayers were classified 2A and unlikely to be called up to the service.

28 “Where Jackson Goes, Williams Follows,” The Sporting News, March 3, 1919, 3.

29 Ibid.

30 “Baseball Season Will Close Sept. 1,” New York Times, August 3, 1918.

31 “Comiskey Wipes 2 Shipbuilders Off Roster,” Chicago Tribune, June 12, 1918, 11. Happy Felsch also quit the team later in the season to go work in a shipyard.

32 Bob Hoie, “1919 Baseball Salaries and the Mythically Underpaid Chicago White Sox,” Base Ball: A Journal of the Early Game, Vol. 6, No. 1 (Spring 2012), Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 30-31. According to Hoie, “Williams later told Kid Gleason that he would never rejoin the White Sox until they paid him the $183.16 that was owed to him … a claim rebuffed by the National Commission.” It’s unknown whether the White Sox ever did pay him.

33 Jim Leeke, “The Delaware River Shipbuilding League, 1918.” The National Pastime: From Swampoodle to South Philly, SABR, 2013.

34 Ibid.

35 Ibid.

36 James Crusinberry, “Gleason Dispels Doubt Regarding Players’ Return,” Chicago Tribune, February 21, 1919, 11.

37 Hoie, 31.

38 William Gleason, “James and Kerr Will Be Able to Back Up Cicotte and Williams Successfully, If Necessary, Their Pilot Writes.” Washington Post, September 28, 1919, 22.

39 “Got $5,000 After Fourth Game, Says Williams,” Boston Globe, September 29, 1920, 16.

40 Black Sox historian Bob Hoie provides evidence in his Base Ball article, based on American League contract cards now available at the Baseball Hall of Fame, that the White Sox had the third-highest Opening Day payroll among American League teams and the highest total salary payout in 1919 — a far cry from the myth of Charles Comiskey’s miserliness that has endured over the years. For a detailed explanation of the issue, read Hoie’s “1919 Baseball Salaries and the Mythically Underpaid Chicago White Sox.”

41 Hoie, 30-31.

42 I.E. Sanborn, “White Sox Crushed Again, 4 to 2,” Chicago Tribune, October 3, 1919, 21.

43 Billy Evans, “Umpire Fooled by Chicago’s Work,” Evansville Courier, December 19, 1920.

44 “Story of Second Game by Innings,” New York Times, October 3, 1919, 11.

45 Gene Carney, Burying the Black Sox: How Baseball’s Cover-Up of the 1919 World Series Fix Almost Succeeded (Dulles, Virginia: Potomac Books, 2006), 202-03.

46 Boston Globe, September 29, 1920.

47 Quotation from Lefty Williams grand-jury testimony cited in Bill Lamb, Black Sox in the Courtroom: The Grand Jury, Criminal Trial and Civil Litigation (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2013), 58. There were also reports, before Lefty Williams gave his grand-jury testimony in September 1920, that Lyria had placed bets against the White Sox during the Series. It’s unclear when she first learned of the fix.

48 Carney, 203.

49 The best-of-nine experiment lasted only until 1921.

50 Lamb, 59.

51 Carney, 199-205.

52 J.M. Flagler, “Requiem for a Southpaw,” The New Yorker, December 5, 1959. Some sources claim the threat was made against Lyria’s life instead. We do know one thing for sure: The character “Harry F.,” who supposedly made the threat against Williams’s life in Eliot Asinof’s Eight Men Out, was invented by the author. Asinof told Gene Carney in an interview for Burying the Black Sox that he created “Harry F.” for legal reasons, in order to protect his work against copyright theft. See Carney, 204-05.

53 Hugh Fullerton, “Is Big League Baseball Being Run for Gamblers, With Players in the Deal?” New York Evening World, December 15, 1919.

54 Carney, 203. Williams was deposed twice, in May 1923 and January 1924, for Joe Jackson’s lawsuit against the White Sox seeking back pay owed to him. In the latter deposition, Williams was inconsistent about many aspects of the World Series scandal, including when he received the payoff from Chick Gandil and Jackson’s role in the fix. But his testimony is more credible than a second-hand anecdote about Lyria told 40 years after the Series ended, which seems to be the strongest independent evidence that any threats were made against Lefty and/or Lyria. Although it’s impossible to know how truthful they were, Williams, Cicotte, Jackson, and Felsch all made public statements about feeling double-crossed during the Series and that they began playing to win. See, e.g., The Sporting News, October 7, 1920, 2: “Williams and Cicotte said that after the awful howl was raised they decided they had better pitch real ball in the closing games of the Series, but by that time things were so upset on the team because of accusations, threats, etc., that it didn’t make much difference whether the conspirators tried to play ball or not.”

55 “World Series Gate Receipts and World Series Player Shares,” Baseball-Almanac.com. Accessed online at http://baseball-almanac.com/ws/wsshares.shtml on August 11, 2010.

56 For an analysis of baseball’s institutional cover-up of the 1919 World Series fix, read Gene Carney’s Burying the Black Sox.

57 Hoie, 30-31.

58 Baseball-Reference.com.

59 A copy of Shoeless Joe Jackson’s grand-jury testimony transcript is available online at BlackBetsy.com.

60 Lamb, 57-59. Williams’s grand-jury testimony was not made available to the public until 2007 by the Chicago History Museum.

61 Lamb, 141.

62 Baseball-Reference.com Play Index.

63 Ibid.

64 The bill of sale between Jackson and Williams was filed on October 6, 1921, in Chicago; a copy is now held by the National Pastime Museum.

65 “Near Death,” Chicago Tribune, March 30, 1923, 26. The Tribune reported that Williams lapsed into a coma at Columbus Hospital in Chicago, but he came out of it a day later.

66 A February 19, 1924, report filed by a private investigator hired by White Sox counsel Alfred Austrian stated that Lyria had not seen her husband in three weeks. She was working as a waitress at the Seafoam Restaurant at 22nd Street and Michigan Avenue, while he had reportedly traveled to Milwaukee to attend Joe Jackson’s back-pay trial against the White Sox. This letter is now housed in the Chicago History Museum.

67 Louis Gollop, “Black Sox Invade Duluth-Range Ball League,” Duluth News Tribune, June 23, 1922; “Black Sox Close Northern Invasion With Duluth Game,” Duluth News Tribune, July 6, 1922; “Black Sox-Hibbing Teams Clash at Athletic Park,” Duluth News Tribune, July 16, 1922. The “Ex-Stars” went just 4-8 on their 12-game tour of the Mesabi Iron Range in northern Minnesota.

68 Lynn E. Bevill, “Outlaw Baseball Players in the Copper League: 1925-1927,” Master’s thesis, Western New Mexico University, 1988. Accessed online at bevillsadvocate.com on April 5, 2010.

69 Ibid.

70 Lowell Blaisdell, “Mystery and Tragedy: The O’Connell-Dolan Scandal,” Baseball Research Journal No. 11, Society for American Baseball Research, 1982.

71 El Paso Times, August 9, 1926. Williams hit the first batter, threw him out at second base when he tried to advance, and then retired the next 20 in a row.

72 Bevill, “Outlaw Baseball Players in the Copper League: 1925-1927.”

73 Ibid.

74 Gandil abruptly quit the Chino Twins right before the postseason began. Despite two wins by Williams, Chino won the series four games to three.

75 1930 United States Census, accessed online at Ancestry.com. Chicago Telephone Directories, 1931-36, Chicago History Museum.

76 “State Leads in Increase of Population,” Los Angeles Times, December 4, 1937. Charles C. Cohan, “Steady Gain in Population,” Los Angeles Times, December 4, 1938. Lorania K. Francis, “California Now Fifth State in Population,” Los Angeles Times, September 14, 1940. “Southland Important Hub of World Affairs,” Los Angeles Times, January 2, 1941.

77 Index to Register of Voters, Los Angeles County, California, 1938-42, accessed online at Ancestry.com. Burbank City Directories, 1937-42, Burbank Central Library. Lyria’s brother, Lawrence Wilson, a widower, had been living in Burbank since at least 1928 and one of his sons, Louis, was also listed as a truck driver in the Los Angeles County voter rolls.

78 Email to the author from Bob Hoie, August 21, 2010. See also: “Owners File Paving Plea For Lindley Ave.,” Los Angeles Times, November 2, 1953.

79 A copy of the telegram can be found at BlackBetsy.com.

80 Index to Register of Voters, Los Angeles County, California, 1944-46, accessed online at Ancestry.com.

81 David Dunaway, Aldous Huxley Recollected: An Oral History (Walnut Creek, California: AltaMira Press, 1999).

82 Index to Register of Voters, Los Angeles County, California, 1948-54, accessed online at Ancestry.com.

83 Index to Great Register, Orange County, California, 1954-64, accessed online at Ancestry.com; Eddie West, “West Winds,” Santa Ana Register, November 8, 1959.

84 1959 Laguna Beach Criss Cross City Directory, Orange County Public Library; Laguna Beach Historic Survey, Vol. 4, California Department of Parks and Recreation, 1981.

85 West, “West Winds.”

86 “Claude (Lefty) Williams of Sox Fame Dies at South Laguna,” Santa Ana Register, November 6, 1959, B-2; “Certificate of Death: Claude Preston Williams,” filed November 9, 1959, State of California, Department of Public Health. Numerous inquiries by researchers and journalists with Melrose Abbey have failed to uncover the specific location of Williams’s ashes.

87 After Chick Gandil was interviewed by Sports Illustrated in September 1956, Lyria wrote a letter to Katie Jackson on October 16 in which she commented, “I am glad they do not know where we live. We sure would send them chasing if they came here.” This handwritten letter was sold by Christie’s Auctions in 1998.

88 Paul Green, “The Later Lives of the Banished Sox,” Sports Collectors Digest, April 22, 1988, 196-97.

89 Flagler, “Requiem for a Southpaw.” In the same article, Lyria gave additional credence to the idea that they had not forgotten the gamblers’ ominous message: “He was wrong, I guess,” she said, “but he was only a youngster when it happened. All those others were doing it, and he didn’t understand what it really meant and, besides, he was threatened.”

90 In 1981 the Yankees’ George Frazier tied Williams’s record with three World Series losses against the Los Angeles Dodgers. But no one suggested that he had thrown the Series.

Full Name

Claude Preston Williams

Born

March 9, 1893 at Aurora, MO (USA)

Died

November 4, 1959 at Laguna Beach, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.