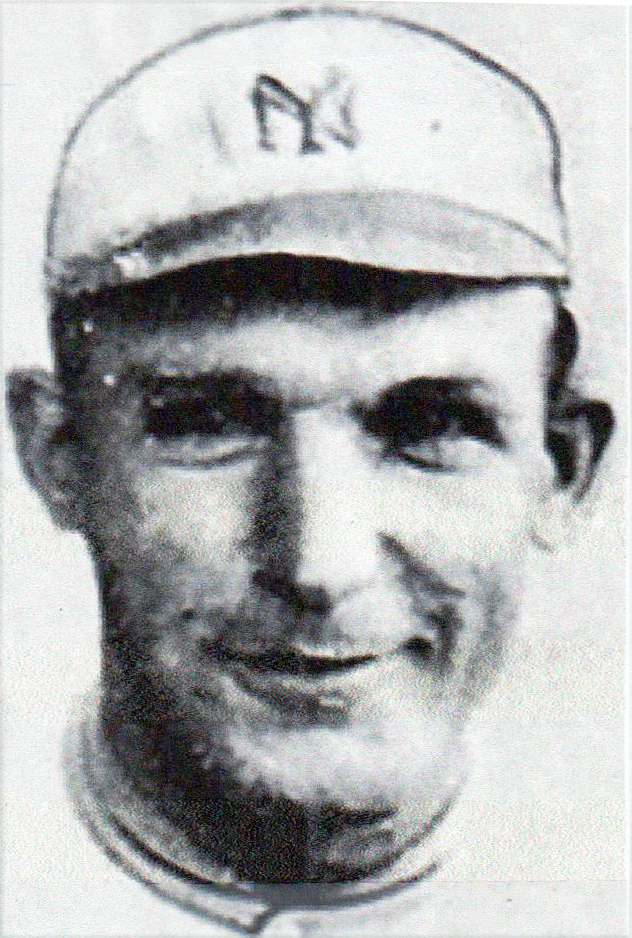

Otis Johnson

Looking back more than a century after his passing, long-forgotten Deadballer Ote Johnson presents a study in contradiction. A multi-tool player, Johnson seemingly possessed the talent required for an extended major league career. Yet his record book entry is confined to the 1911 season with the New York Highlanders.1 The reason perhaps? Every playing asset displayed by Johnson appeared to be offset by a corresponding deficiency. Examples abound.

Looking back more than a century after his passing, long-forgotten Deadballer Ote Johnson presents a study in contradiction. A multi-tool player, Johnson seemingly possessed the talent required for an extended major league career. Yet his record book entry is confined to the 1911 season with the New York Highlanders.1 The reason perhaps? Every playing asset displayed by Johnson appeared to be offset by a corresponding deficiency. Examples abound.

A switch-hitting shortstop, Johnson demonstrated long-ball power sufficient to be a minor league leader in home runs. At the same time, he hit for a low average and struck out frequently by era standards. Ditto on defense. At one point or another during his 13-year professional career, Johnson’s natural athleticism placed him at every position on the diamond. But he was a substandard defensive player at most of them. A powerful throwing arm prompted periodic use of Johnson as a pitcher, but arm miseries hampered his lone season in the big leagues. Sober and hardworking with an outgoing personality, Ote was a favorite of teammates, club management, baseball fans, and the sporting press. Notwithstanding that, he sabotaged his first major league audition by antagonizing Highlanders field leader George Stallings. Even Johnson’s demise reeked of contradiction. Physically fit and brimming with good health, he died young; an offseason hunting accident ended Ote Johnson’s life at age 32. His story follows.

Otis L. Johnson was born on November 5, 1883, in Fowler, Indiana, a small town situated near the Illinois border. He was the younger of two sons2 born to New Jersey native George Edward Johnson (1854-1917) and his Indiana-born wife Viola (née Cory, 1861-1931), both church-going Methodists. When Ote (as he was usually called) was still a boy, the Johnson family relocated across state to Muncie, a commercial and industrial hub located 50 miles northwest of Indianapolis. There, father G. Edward secured long-term employment as a factory night watchman. The extent of Ote’s schooling is unknown but by the time of the 1900 US Census, the teenager was working in the same handle-making plant that employed his father. Johnson was also beginning to attract attention as a baseball prospect playing with Muncie area sandlot, amateur, and semipro nines.3

In January 1903, Ote took a bride, marrying a 16-year-old local girl named Edith (maiden name unknown). In time, the couple had two children, Mabel Elizabeth (born 1904) and William Otis (1908). Several months after his marriage, Johnson entered the ranks of professional baseball, signing with the Dallas Giants of the Texas League (then Class D).4 A sturdily built (5-foot-9, 185 pounds) switch-hitter who swung from the heels, he promptly established what would become a career-long hitting pattern, posting a low (.216) batting average coupled with long ball power (12 homers, third-highest among circuit batters). Primarily an erratic shortstop (.880 fielding percentage),5 the strong-armed Johnson also pitched the odd exhibition game for Dallas.

With the Texas League elevated to Class C for the 1904 season, Johnson returned to Dallas for his sophomore campaign. In 100 games, he upped both his batting (.260) and fielding (.899) percentages,6 and smacking a team-leading 10 dingers earned him the nickname Home Run. When the Texas League season abruptly ended in mid-August, the cash-strapped Dallas club sold Johnson to the Little Rock Travelers of the Class B Southern League.7 Installed as the everyday shortstop, he got by with the bat (.232 average) and glove (.913 fielding percentage) in 20 games. He was retained by Little Rock for the coming season.

Playing for last-place Little Rock clubs the next two years, Johnson’s career stalled. During that period, he alternated between short, third base, and the outfield – and batted so poorly that he was deemed more of a pitching prospect (2-6 in 12 games) by 1906.8 Johnson began the following campaign in the Class C South Atlantic League, pitching for the Charleston Sea Gulls. But two early season homers prompted his shift to first base. By mid-season, Ote was the club’s regular shortstop. In 121 games, he batted a solid .263 with 12 home runs in the weak-hitting loop,9 while chipping in a 5-3 log on the mound for the league champion (75-46, .620) Sea Gulls.

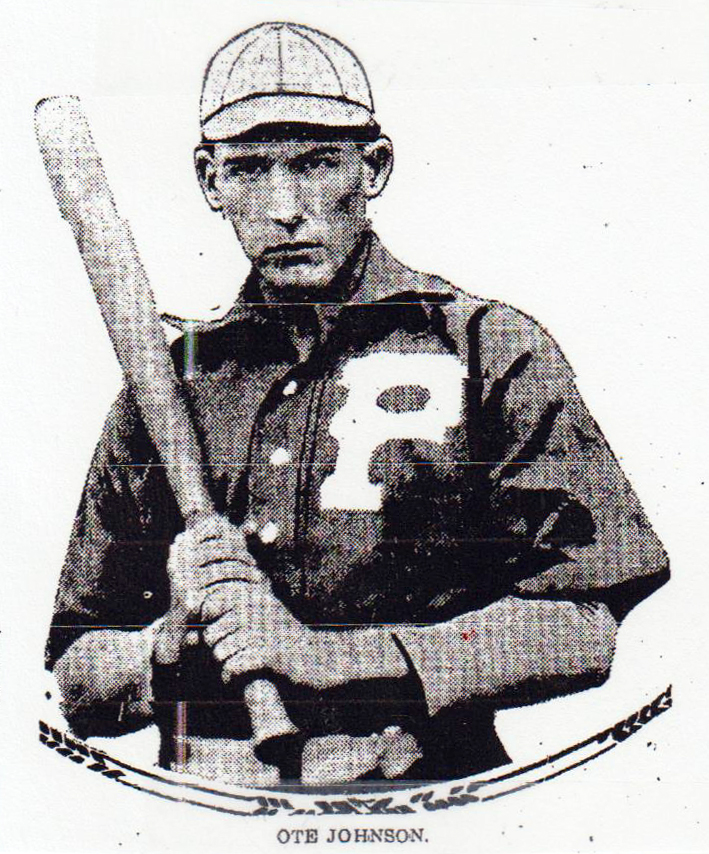

In late August, Charleston sold the contract of “the premier long-distance hitter of the circuit” to the Portland Beavers of the Class A Pacific Coast League.10 Used almost exclusively at shortstop, Johnson fielded tolerably (.932) but batted only .215 in 41 games for his new club. Still, that was good enough for the last-place (72-114, .388) Beavers to bring Johnson back for another season.

Both the Portland Beavers and Ote Johnson made giant strides in 1908. Over a grueling seven-month schedule, Portland improved to 95-90-2 (.514), good for second place in the four-club PCL. Much of the improvement was attributable to the versatile Johnson, who hit the ball hard – a .281 average with team leadership in homers (10), extra-base hits (61), slugging average (.430), and total bases (282). He also saw defensive action all over the diamond. In the opinion of Beavers pitcher Jesse Garrett, “Ote Johnson was the best of the players in the PCL. His regular position is third base but he played every position in the infield and pitched and caught several games. He is hitting them in terrific fashion and covers a lot of ground.”11 The local press concurred, declaring that “Johnson was the star all-around player of the league.”12 Such acclaim, however, was not enough to get Ote selected during the late-season draft of minor league players by big league clubs. Portland was, therefore, delighted to have him back for 1909.

Portland and Johnson continued to progress in the new year. The Beavers improved to 122-87 (.583), good for second place in a PCL expanded to six clubs. Playing in 205 of his club’s 209 regular season games, Johnson was a standout. He paced the circuit with 13 home runs and finished second in the league batting race with a .293 average. Ote was also the Portland club leader in runs (108), base hits (195), doubles (41), slugging average (.432), and total bases (287). All in all, Johnson was “one of the most dangerous batsmen” in the Pacific Coast League.13 His defense at the hot corner, however, was shaky; Johnson’s 57 errors were tops among PCL third basemen for the 1909 season. Yet while “not a great star in the fielding line,” Johnson was “a steady, conscientious player and possesses one of the best throwing arms of any infielder in the league,” observed the Morning Oregonian.14 He was also “one of the most popular players on the team.”15

Portland and Johnson continued to progress in the new year. The Beavers improved to 122-87 (.583), good for second place in a PCL expanded to six clubs. Playing in 205 of his club’s 209 regular season games, Johnson was a standout. He paced the circuit with 13 home runs and finished second in the league batting race with a .293 average. Ote was also the Portland club leader in runs (108), base hits (195), doubles (41), slugging average (.432), and total bases (287). All in all, Johnson was “one of the most dangerous batsmen” in the Pacific Coast League.13 His defense at the hot corner, however, was shaky; Johnson’s 57 errors were tops among PCL third basemen for the 1909 season. Yet while “not a great star in the fielding line,” Johnson was “a steady, conscientious player and possesses one of the best throwing arms of any infielder in the league,” observed the Morning Oregonian.14 He was also “one of the most popular players on the team.”15

Johnson’s performance did not go unnoticed by major league ball clubs, and in mid-August the New York Highlanders acquired his contract for a reported $4,000.16 Like other minor league talent being stockpiled by New York club boss Frank Farrell, Johnson was instructed to complete his minor league campaign and thereafter report for spring training with the Highlanders in 1910. In the interim, Ote returned home to Muncie, where he earned $6-$7 per day as a glass blower at a fruit jar plant.17

Johnson showed well in spring camp and was expected to supplant light-hitting Jimmy Austin as the New York third baseman. Enthused Highlanders manager George Stallings informed onlookers that he thought that Johnson would “make a great name for himself this season.”18 Ote made the Highlanders’ Opening Day roster, but inexplicably saw no game action during the season’s first week. It was then revealed that “trouble arose between him and the manager [Stallings] shortly after the opening of the season and rapidly developed into an open fight.”19 The cause of the friction was not publicly disclosed – but before he ever saw action in a regular season major league game, Johnson was banished to the Jersey City Skeeters of the Class A Eastern League.20 The Highlanders retained an option on Johnson’s services, but the normally affable ballplayer was bitter about his treatment, declaring that he would “quit playing baseball before he will work under present New York management.”21

Johnson’s performance in Jersey City livery was so poor as to render moot his return to New York anytime soon. By mid-June, a .186 batting average had him relegated to the Jersey City bench.22 His bat revived when restored to the Skeeters lineup; his average was up to .223 at season’s end. And he showed power. Johnson’s 35 extra-base hits included a team-leading nine home runs while his slugging average (.364) was second-best.

Meanwhile in New York, events were turning in Johnson’s favor. A tumultuous public row led to the ouster of nemesis Stallings as Highlanders manager, with slick-fielding first baseman Hal Chase installed as his late-season replacement.23 Over the winter, new skipper Chase revealed that he intended to shift incumbent Highlander shortstop Jack Knight to second base and try out the exiled Johnson at shortstop.24 Eastern League President Ed Barrow voiced his approval of the plan, stating that “Otis Johnson will make good with the Highlanders. He can field as well as anybody and is a terrible sic] hitter in the pinch. With men on bases Johnson has a world of confidence in himself and is a terror to pitchers.”25 For his part, Johnson was thrilled to have another chance in New York under a different manager. “I said I would be back in the big leagues if I had to sneak over here in my nightshirt,” joked Ote. “Now, I am back and just watch them get me out of the league.”26

In his second Highlanders spring camp, Johnson started slowly. But his bat heated up in time for him to again make the club’s regular season roster. On April 12, 1911, Ote Johnson made his major league debut as the New York shortstop in an Opening Day match against the defending world champion Philadelphia A’s at Shibe Park. Behind the three-hit pitching of Hippo Vaughn, the Highlanders won, 2-1, with Ote scoring the decisive run in the top of the eighth. Otherwise, Johnson’s performance (0-for-2 at the plate, and an error in six chances at short) was forgettable. He broke into the hit column the following day with a triple (and a walk) off A’s right-hander Jack Coombs in a 3-1 New York victory.

From there, Johnson’s stick faltered. A report by New York sportswriter Bozeman Bulger pointedly commented that the “new Highlander player [was] not batting hard enough to keep himself warm.”27 Two games after striking out in all three of his at-bats, “Home Run” Johnson clubbed his first major league four-bagger, a two-run shot off right-hander Charlie Smith in a 4-3 Highlanders win in Boston on April 27. But soon thereafter Ote was bedeviled by off-field problems. In mid-May, he left the club for several days to visit his ailing mother in Muncie.28 Shortly after returning to the club, Johnson was back in Indiana instituting divorce proceedings against his wife.29 Edith Johnson had deserted her husband and taken up with another man.30

Ote’s play picked up in May, and previously critical Bozeman Bulger sang his praises. “Otis Johnson has done some wonderful fielding and throwing at short. He has also shown himself a wonder at reaching base via the four-ball route,” wrote Bulger in early June. But Johnson’s hitting was “not as heavy as was expected,” and the return of Knight to shortstop was predicted by the scribe.31 Shortly thereafter, manager Chase made the switch, moving Knight over from second base and installing Earle Gardner at the keystone.32 Johnson’s prospects for regaining his position were then jeopardized by the need to return to Indiana for proceedings on his divorce suit. When Edith Johnson failed to appear, Ote was granted the sought-after decree and awarded custody of his two children, as well.33

Upon his return to New York, Johnson was sidelined for a month by throwing arm miseries.34 He made an emergency appearance in a mid-July game in Cleveland – Ote had been left behind on the road trip and had to “answer an S.O.S” in order to fill in at second base.35 But he was “still having a great deal of trouble with a bad arm … [and] it gives him a great deal of pain to throw the ball across the diamond.”36 Bad wing notwithstanding, Johnson had a productive burst the following week, registering a quartet of two-hit games that included home runs on July 25 and 26, in the second game of a doubleheader. Immediately thereafter, an 0-for-15 skid returned Ote to the bench, and from there on he saw only sparing action until season’s close.

In all, Johnson made 71 game appearances for the 1911 New York Highlanders. His.234 batting average (49-for-209) was well below the club norm (.272), but his on-base (.363) and slugging (.378) percentages were modestly above average. Expected to supply the long ball, Johnson had been a disappointment, with only three homers counted among his 18 extra-base hits. He had also been less than stellar on defense, posting substandard fielding percentages at short (.907 in 47 games), second (.897 in 15 games), and third base (.909 in three games).37

After guiding his club to a sixth-place finish, manager Chase was relieved of command, and Johnson did not fit into the plans of incoming skipper Harry Wolverton. Over the winter, his contract was sold to the Rochester Hustlers of the Class AA International League.38 At age 28, Ote Johnson’s major league days were behind him.

Once again, Johnson was unhappy with his treatment by New York, asserting that “he should have at least been given the opportunity of accompanying the Highlanders this year on the spring training trip.”39 Still, Johnson resolved that he would be “going back to the big show” as soon as he fulfilled his one-year contract with Rochester.40 But before embarking on that campaign, Ote had another announcement to make: his engagement to 22-year-old burlesque dancer Violette Dusette.41 On May 21, 1912, the couple tied the knot in the rectory of St. Luke Episcopal Church in Rochester at noon, and then departed for the Hustlers ballpark. With his new bride watching from the stands, Ote’s 10th-inning double brought Rochester a 4-3 victory over Baltimore.42

Johnson went on to post facially solid numbers for his new club, (.264 batting average/.411 slugging) with a club-leading 52 extra-base hits. But his 44 errors were worst among International League second basemen,43 and the locals were plainly dissatisfied with Johnson’s performance. At season’s end the leading Rochester newspaper took aim at Ote’s $2,750 salary, sneering, “that salary would be all right for a player able to deliver the goods, but Johnson didn’t show much better than $250 a month quality.”44 Club management evidently felt the same way, selling Johnson’s contract to the Binghamton Bingos of the Class B New York State League that November.45

Johnson feasted on lower-level minor league pitching. In 136 games, he posted a career-best .323 batting average. He also fielded well at both shortstop (.951 in 100 games) and second base (.956 in 34 games).46 Ote even did a little late-season pitching and catching for Binghamton.47 Duly impressed, the St. Paul Apostles of the Class AA American Association scooped up Johnson in the postseason minor league player draft.48 But his stay in St. Paul was relatively brief. After 45 games, Johnson was back in the New York State League, sold to the Elmira Pioneers.49 And as before, he enjoyed Class B pitching, smashing a circuit-leading 13 home runs50 in only 94 games. He also played a capable shortstop (.958 fielding percentage) for the pennant-winning (90-48, .652) Pioneers. Elmira therefore reserved him for the next season.51

Although only 31 and coming off a productive minor league season, Ote Johnson was no longer a major league prospect. But with his young family gathered about him and gainfully employed by a shoe manufacturing plant in the offseason, Johnson seemed happily settled in western tier New York. He returned to Elmira in 1915 and posted stat totals that bore many career hallmarks: Deadball Era-lofty home runs (14), walks (80), and strikeouts (74),52 with mediocre defense (.928 in 126 games) at shortstop. Once again at season’s end, the ball club promptly reserved him for the oncoming year.53

On November 9, 1915, Johnson and several friends spent the day rabbit hunting near Oswego.54 At around 3:00 that afternoon, one of the party winged a fox. In pursuit of the wounded animal, Johnson stumbled and fell, accidentally discharging both barrels of his shotgun into his abdomen. Bleeding profusely, he was driven at breakneck speed to a nearby hospital. Despite being in considerable pain, Ote maintained his sense of humor during the trip. “Oliver,” he informed the driver, “it’s better that one should die than for you to kill all of us to save me.”55 Johnson survived the harrowing car ride, but his massive internal injuries proved irreparable. Otis L. “Ote” Johnson died at Johnson City Hospital shortly after 4:00 PM.56 Only four days before, he had celebrated his 32nd birthday.

News of Johnson’s passing stunned area residents. One recalled that Ote “was always willing to do a favor for a friend, always even-tempered and withal a ‘hale fellow well met.’”57 Following a funeral service concelebrated by Episcopal and Methodist clergymen, the deceased was laid to rest in Floral Park Cemetery, Johnson City. Survivors included second wife Violette, children Mabel and Billy, his parents, and brother Bill Johnson.

Acknowledgments

This biography was originally published in the August 2023 issue of The Inside Game, the quarterly newsletter of the Deadball Era Committee

This version was reviewed by Gregory H. Wolf and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Tony Oliver.

Sources

Sources for the biographical detail provided above include the Otis Johnson file maintained at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York; US Census and related data accessed via Ancestry.com; articles on Johnson published on-line by Baseball History Daily, October 10 and 17, 2013; and certain of the newspaper articles cited in the endnotes. Unless otherwise specified, stats have been taken from Baseball-Reference and Retrosheet.

Notes

1 By 1911, the more headline-friendly Yanks or Yankees had largely supplanted Highlanders as the unofficial nickname of the American League Base Ball Club of Greater New York. But in the writer’s view, a certain clarity is achieved by using Highlanders for the club during its tenure at Hilltop Park (1903-1912) and reserving Yankees for thereafter.

2 Ote’s only sibling was older brother William, born in 1876.

3 Johnson also garnered press notice as a running back/kicker for Muncie’s semipro football team. See e.g., “Football Material for Muncie’s City Team,” Muncie (Indiana) Morning Star, September 6, 1902: 2.

4 See “Dallas vs. Paris,” Dallas Morning News, May 5, 1903: 4. Johnson was signed on the recommendation of Dallas catcher Claude Berry, a fellow Muncie resident.

5 Per the 1904 Reach Official American League Guide, 268.

6 Per the 1905 Reach Official American League Guide, 272.

7 As reported in “Near End of Season,” Dallas Morning News, August 14, 1904: 11. The Southern League became a Class A circuit in 1905.

8 A late-season doubleheader that Johnson pitched against Atlanta included a two-hit shutout deemed “one of the greatest games ever seen on the Little Rock diamond,” according to a Little Rock Daily News commentary reprinted in the Muncie (Indiana) Evening Press, September 16, 1905: 6.

9 Sea Gulls teammate Tom Raftery handily won the league batting title with an unspectacular .301 mark, while the champion Charleston club posted a meager .217 average as a team.

10 See “Gossip of the Diamond,” (Portland) Sunday Oregonian, September 8, 1907: 37; “Signs Two Cracks,” Morning Oregonian, August 21, 1907: 7. The purchase price was $500.

11 “Garrett Is Back from Coast,” Dallas Morning News, November 7, 1908: 11.

12 “Ote Johnson Is Star Performer,” Morning Oregonian, November 21, 1908: 7.

13 P.J. Petrain, “Two Players Sold,” Morning Oregonian, August 7, 1909: 7.

14 Same as above.

15 Same as above.

16 As reported in “Yankee Manager Unearths a Find,” Washington (DC) Times, August 15, 1909: 12; “Ote Johnson Will Go to the New York Americans,” San Luis Obispo (California) Telegram, August 11, 1909: 6; and elsewhere.

17 Per “Ote Johnson Now in the Limelight,” Muncie Evening Press, February 5, 1910: 8.

18 Per a wire service article “Otis Johnson, Third Sacker, From Whom Great Things Are Expected,” published in various New Jersey dailies. See e.g., (Bridgewater) Courier-News, April 4, 1910: 5; Perth Amboy Evening News, April 1, 1910: 9; Trenton Evening Times, April 1, 1910: 8.

19 Per “Johnson Not with Yanks,” Muncie Evening Press, May 2, 1910: 3.

20 See “American Leaguers in Fight,” Courier-News, May 11, 1910: 9; “Otis Johnson in Jersey City Uniform,” (Jersey City) Jersey Journal, April 28, 1910: 3.

21 Per “Johnson Sent Back to Jersey City, N.J., Team,” Muncie Morning Star, May 10, 1910: 8. In another outburst, Johnson stated that if recalled by New York “he hoped that [Stallings] would be dead,” adding that he “would take nothing from the manager but the money to pay the fine for whipping him.” See “Johnson Not with Yanks,” Muncie Evening Press, May 2, 1910: 3.

22 Per “Chummie’s Column,” (Portland) Oregon Journal, June 18, 1910: 10.

23 Stallings had publicly questioned the integrity of Chase’s play, much to the displeasure of American League President Ban Johnson, then an ardent supporter of the flashy first baseman. Under backstage pressure from Johnson, New York club boss Frank Farrell subsequently discharged Stallings and gave the manager’s post to Chase.

24 See “Ote Johnson Will Join ‘Comebacks,’” Oregon Journal, December 9, 1910: 17; “Shift Knight to Second,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, December 8, 1910: 11; “Trenton Team at Willard Park,” Paterson (New Jersey) News, December 3, 1910: 6.

25 “President Barrow Says ‘Ote’ Johnson Sure to Make Good,” Oregon Journal, January 29, 1911: 34.

26 “Pulling for Ote Johnson,” Charleston (South Carolina) Evening Post, February 2, 1911: 3.

27 See “Otis Johnson Will Have to Improve with Stick to Keep Job at Shortstop,” New York Evening World, April 19, 1911: 14.

28 As reported in “Ote Johnson Is Home to Visit Sick Mother,” Muncie Evening Press, May 14, 1911: 10. Viola Johnson recovered her health in due course and long outlived her son.

29 Per “Ball Player Asks Divorce,” Muncie Evening Press, May 22, 1911: 8.

30 The 1910 US Census places Edith Johnson and children under the roof of one Hale Silver in Salt Lake City.

31 Bozeman Bulger, “Highlanders Bank on Gardner to Brace Up Oft-Changed Infield,” New York Evening World, June 6, 1911: 16.

32 As reported by F.A. Perner, “Former Coasters Batting Over .300 Mark,” San Francisco Chronicle, June 18, 1911: 57: “Ote Johnson has been benched for weak hitting.”

33 Per “Ote Gets Divorce,” Cincinnati Post, June 23, 1911: 9; “Court Record,” Muncie Evening Press, June 22, 1911: 11.

34 See J. Ed Grillo, “Pertinent Comment on Happenings in Sportdom,” Washington Evening Star, June 23, 1911: 15. See also, “Sporting Writer Praises Johnson,” Muncie Evening Press, July 25, 1911: 3, quoting the commendation of Johnson by sportswriter Mark Roth in a recent New York Globe column.

35 Per “Krapp to Pitch for Cleveland Today,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 18, 191: 7.

36 “A Few Short Ones,” Albuquerque (New Mexico) Morning Journal, July 20, 1911: 4.

37 Johnson’s fielding numbers were markedly inferior to those posted by Earle Garner at second base (.959 FA in 101 games) and Roy Hartzell at third (.936 in 122 games), but no worse than the below par figures of replacement shortstop Jack Knight (.907 FA in 80 games).

38 As reported in “Bumpus Jones Sold to Ganzel for $2,500,” Jersey Journal, December 13, 1911: 9; “Wolverton Will Stick to Chase,” Morning Oregonian, December 11, 1911: 10; and elsewhere.

39 “Otis Johnson Should Prove Tower of Strength to the 1912 Hustlers,” (Rochester) Democrat and Chronicle, February 14, 1912: 10.

40 Same as above.

41 See “Ote Johnson Will Wed Apache Dancer,” Jersey Journal, April 5, 1912: 9; “Vaudeville Star to Marry Otis Johnson,” Democrat and Chronicle, April 3, 1912: 21. The two had met the previous summer when both were performing in Chicago.

42 See “Rochester 4, Baltimore 3,” Providence Evening Bulletin, May 21, 1912: 16. See also, “Otis Johnson Weds an Eastern Actress,” Muncie Morning Star, May 23, 1912: 8; “Otis Johnson, of Muncie, Wins Game for Rochester of International League in Tenth Inning on His Wedding Day,” Muncie Evening Press, May 22, 1912: 7.

43 Tied for IL worst actually, per stats from the 1913 Reach Official American League Guide, 237.

44 Democrat and Chronicle, October 20, 1912: 34.

45 As reported in “Ote Johnson Toboggans to the N.Y. State League,” Jersey Journal, November 9, 1912: 11; “Bingos Strengthening Club,” Watertown (New York) Times, November 7, 1912: 6; and elsewhere.

46 Per the 1914 Reach Official American League Guide, 283-284.

47 Johnson alternated ably between both positions during a 9-7 loss to Elmira on September 14.

48 As noted in the Buffalo Evening News, October 9, 1913: 18.

49 Per “Otis Johnson Joins Elmira,” Elmira (New York) Star-Gazette, June 9, 1914: 8; “International League Clubs Show Up Big Leaguers,” Newark Evening Star, June 6, 1914: 16. The Johnson purchase price was “nearly $1,000.”

50 Per the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, eds. (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, 3d ed., 2007), 252.

51 Per the Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) Times-Leader, October 19, 1914: 15.

52 Per NYS League stats published in the Elmira Star-Gazette, September 8, 1915: 8. The league season ended five days thereafter. See also, the 1916 Reach Official American League Guide, 248, 252.

53 See “Sixteen Men Are Reserved for the Colonels,” Elmira Star-Gazette, October 25, 1915: 8.

54 The events attending the fatal hunting trip were recounted in the national, local, and sporting press. See e.g., “Rabbit Hunt Fatal to Otis Johnson, Ball Player,” Indianapolis Star, November 10, 1915: 11; “Johnson Succumbs to Gun Wound Sustained Hunting Near Oswego,” Elmira Star-Gazette, November 10, 1915: 20; “Victim of Accident,” Sporting Life, November 27, 1915: 16.

55 “Johnson Dies of Injuries,” Berkshire Evening Eagle (Pittsfield, Massachusetts), November 11, 1915: 14. See also, “Details of Tragic Death of Former Muncie Ball Player,” Muncie Evening Press, November 17, 1915: 6.

56 The Johnson death certificate lists shock as a contributing factor to his demise.

57 “Details of Tragic Death,” above.

Full Name

Otis L. Johnson

Born

November 5, 1883 at Fowler, IN (USA)

Died

November 9, 1915 at Johnson City, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.