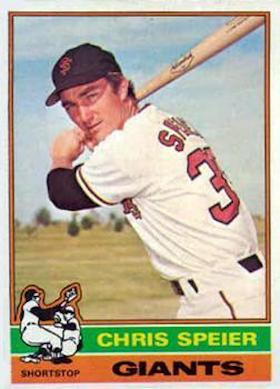

Chris Speier

It wasn’t unusual that Chris Speier was a Bay Area dude who played for the San Francisco Giants, nor that he was discovered by a major league scout while playing semi-pro ball. But for a California dude to be discovered playing ball in a Canadian town better known for its annual Shakespeare festival than for baseball? Now that’s unusual!

It wasn’t unusual that Chris Speier was a Bay Area dude who played for the San Francisco Giants, nor that he was discovered by a major league scout while playing semi-pro ball. But for a California dude to be discovered playing ball in a Canadian town better known for its annual Shakespeare festival than for baseball? Now that’s unusual!

Chris Edward Speier was born on June 28, 1950, in Alameda, California, to Wes and Marcene Speier. He graduated from Alameda High School in 1968. He also played in local leagues, one time going 6-for-7 in a game for the Alameda Athletic Association with two doubles and five RBIs.

Speier’s local reputation encouraged the Washington Senators to draft him in the 11th round of the 1968 amateur draft. He chose instead to play college ball at the University of California Santa Barbara , and made the varsity squad as a freshman. While there, his opportunity to try life above the 49th parallel came about when his college team’s pitching coach, Rolf Scheel, invited him to join the Stratford Hoods of the Intercounty Baseball League, where Scheel went to pitch.

“Most of the fellows were older types – much older than I was,” recalled Speier. “Each team was allowed to use four imports and Mr. Hannah used to scout the league pretty closely.”1

The Intercounty League has been in existence since 1919 and consists of teams from southern and eastern Ontario. It was easy for Detroit-area scouts to cross the border to look for players. One of them, the Giants’ Herman Hannah, saw Speier and convinced the Giants to draft him.

Speier became the second overall pick in the 1970 January draft.2 Even though he was only19 , the Giants thought enough of his ability to have him skip Class A, sending him instead to Class AA Amarillo of the Texas League. After a slow start, he reached the point where, by his own assessment, he was playing more consistently but needed to improve.

“I feel I’m doing a competent job,” he said in an interview. “I have to improve on everything. I must learn to hit better.”3

He improved enough to hit .283, with six home runs and 66 RBIs. His numbers gave him a chance at the starting shortstop job when the Giants convened for spring training in 1971. His competition was the incumbent, Hal Lanier, who had played the position with San Francisco for the previous seven seasons. Speier wanted Lanier’s job and began working to get it even before spring training began. That work ethic prompted some people to think he was a bit off his rocker.

“Chris Speier began his campaign for Hal Lanier’s shortstop job long before spring training opened,” wrote Jack Hanley in The Times of San Mateo California. “In early January he reported daily to Candlestick Park to run wind sprints. Construction workers giving Candlestick a new look thought he was some kind of nut.”4

Speier obviously didn’t care what others thought because that work led to a marvellous training camp and the starting shortstop job at the age of 20 and with only one year of professional ball behind him. He not only hit well and played solid defense, he infused the team with a youthful enthusiasm that even affected jaded veterans such as Willie Mays.

“It’s easy to lose interest when the club isn’t going well,” the Say Hey Kid said, “but I’ll tell you I’m all excited this year and I have to say it’s all because of the kid shortstop. What I like best about him is that he isn’t cocky.”5

Giants’ manager Charlie Fox was just as effusive in praising his young shortstop.: “Speier is making plays we haven’t been able to make before,” Fox said. “Lanier has played outstanding shortstop for us over the years. But Speier has tremendous range and skill and throwing ability…This kid reminds me of Pee Wee Reese, who was one of the best.”6

For the year, Speier hit .235 with eight home runs and 46 RBIs. The accolades from teammates and management didn’t translate into any votes for Rookie of the Year (Earl Williams of Atlanta won the award), but he did help the Giants win the National League West Division. They lost the National League Championship Series to the Pittsburgh Pirates in four games despite Speier’s .357 average.

After a highly successful rookie year, Speier felt he deserved a raise and, doing his own negotiating, saw his sophomore season salary jump to a reported $20,000 from a rookie stipend of $12,500. With his new contract in hand, Speier decided to try becoming a switch-hitter. He experimented with the idea all through spring training in 1972 and into the first few games of the season. He resumed hitting exclusively from the right side by mid-April, simply because he wasn’t confident hitting left-handed.

Abandoned experiment notwithstanding, Speier had career highs in home runs (15) and RBIs (71) and hit .269. He also made the first of three consecutive All-Star teams. He went 0-for-2 with a sacrifice in the Classic as the National League defeated the American League 4-3. But despite his personal accomplishments, Speier could not prevent the Giants from plummeting to fifth place, going 69-86.7 He did, however, make the team’s highlight film watchable, according to teammate Willie McCovey.

“After the season we had last year, I didn’t think they could get 26 minutes

of good film,” the Hall-of-Fame first baseman said. “Thank goodness for Chris Speier.”8

He also began enjoying married life when he tied the knot with Aleta Pagnini of Medford, Oregon. Aleta not only brought his carefree bachelor days to an end, she also had a profound effect on him spiritually.

“When I started playing I was a roustabout,” he said. “I was single and I caroused. But the one thing that she showed me that really turned me on was the way to God…With me God and my family are one-two; baseball is third.”9

Speier’s two goals for the 1973 season were for the Giants to win and to cut down on his career-high 92 strikeouts from the previous season. The latter objective seemed easier to accomplish after the team’s awful 1972 campaign. Somehow, though, they defied the experts. After a hot 15-5 start, they played better than expected and finished at 88-74. Although Speier’s average dropped to .249, he hit 11 home runs and equalled his career high of 71 RBIs. He played in the All-Star Game again, going 0-for-2, and cut his strikeout total to 69.

Another All-Star selection in 1974 did little to counter a frustrating season for both Speier and the Giants. At one point in June, he was briefly moved to second base and replaced at shortstop by Bruce Miller. Chris was one of a number of players who criticized manager Charlie Fox for how he handled the lineup – Fox was fired on June 27 – and had another mediocre season at the plate (.250, nine home runs and 53 RBIs). The Giants floundered, finishing in fifth place in the NL West with a 72-90 record.

One of the contributing factors to that terrible season was all the second fiddles who played third base for the team, as six different players spent time there during the campaign.10 When spring training for 1975 began, the club’s brain trust toyed with the idea of moving Speier to the position.

Prior to 1975, the hot corner had scalded 44 other players since the Giants moved to San Francisco from New York. Even Orlando Cepeda (four games in 1959) and Mays (once in 1964) played there. Such a move clearly didn’t come with a lot of job security, but fortunately for Speier, management left him at short and pencilled in Steve Ontiveros as their Opening Day third baseman. The Ontiveros experiment didn’t work, as the team used seven men there during the season. Even Speier played a game there.11 Despite the infield instability, the Giants were a much better team, going 80-81 under Wes Westrum. Speier’s offensive numbers improved as well: .271 with 10 homers and 69 RBIs. He also had better defensive numbers: only 12 errors , the first time in his career that he had fewer than 20 in a season. Speier attributed his better play to a more positive overall outlook.

“I re-evaluated myself during the winter,” Speier said, “and tried to put my priorities in order. I think I’m in the best mental and physical shape of my career.”12

Prior to the 1976 season, Speier and his teammates had to deal with the distraction of a potential sale of the Giants by longtime owner Horace Stoneham to a group in Toronto. It wasn’t until spring training was well underway that the issue was settled when a local ownership group headed by Bob Lurie bought the team for $8 million and kept them in San Francisco.

Neither the team nor Speier performed well early in the season. In what turned out to be a harbinger of things to come, the Giants made two moves that indicated that management was not pleased with how the shortstop position was being handled. They acquired Marty Perez from the Braves on June 13, and started him at shortstop 12 times during the season. Perez, at 30, was four years older than Speier. In August they brought Johnnie LeMaster up from the minors, intending to start him at shortstop and move Speier to second base. Speier balked at the move, a decision that led manager Bill Rigney to play him sporadically the rest of the month. In one of his rare starts, a 5-4 16-inning win at home against Montreal on August 21, he played first, second and third, but not short. The Giants limped to a 74-88 record, Speier batting just .226 with three home runs and 40 RBIs. A change of scenery and a reunion with an old friend beckoned.

The 1976 Montreal Expos were, to put it mildly, a disaster, with a 55-107 record. A regime change was in order, and that included Speier’s former manager Fox assuming the general manager’s role. His shortstop going into the 1977 season was Tim Foli, a volatile personality whose temper tantrums had alienated him from his teammates. Speier, on the other hand, was not happy in San Francisco because of both his contract and the direction the team was headed. The two clubs swapped shortstops on April 27, 1977.

“If you put Tim Foli and Chris Speier in a room and asked me to choose the man that I think would help us the most to become winners, I’d choose Speier,” said Fox. “It’s that simple. We feel we can win with Speier.”13

Speier was delighted to go to Montreal, “because I’m looking forward to being with a team that goes about getting the players necessary to win. I think that the Expos made very positive moves over the winter by getting Dave Cash and Tony Perez and I’m elated to think that I’m going to a team that thinks that way.”14

Happy though he may have been, it took some time before Expos fans warmed up to him. Speier joined the club while they were on a west coast trip and started poorly. He was rusty after spending most of the early season on the bench; he appeared in only six of the Giants’ first 15 games. During his first home stand as an Expo, the fans booed lustily after he went 0-for-10 in a doubleheader loss to the Cubs. His play steadied, and by the end of the season, fans knew that acquiring Speier was a good move despite the mediocre numbers (.234 batting average with five home runs and 38 RBIs).

Speier became a rarity among Expos players in that he didn’t hightail out of town as soon as the season was over. He bought a cottage in the resort town of St. Adele, 45 miles north of Montreal, and eventually the family lived there year round. His children learned to speak French at school and with their friends, and his daughter Erika even sang the Canadian national anthem en francais at an Expos game.

The highlight of Speier’s 1978 season came on July 20 when he hit for the cycle and drove in six runs during a 7-3 victory over the Atlanta Braves at Olympic Stadium. It was the second cycle in team history and the first since his predecessor, Foli, performed the feat in 1976 against the Cubs.

Controversy preceded Speier’s accomplishment. He had gone 1-for-18 at the plate since the All-Star break and was getting an earful from Fox before the game when team player representative Steve Rogers intervened on Speier’s behalf. Rogers and Fox soon came to blows.

The Expos underachieved in 1978, going 76-86 when a number of people expected them to contendfor the division title. Speier though, had a comeback of sorts. He played 150 games, his highest total since 1973, with a .251 batting average, five home runs and 51 RBIs.

The team came of age in 1979, going 95-65 and coming within one game of the National League East Division title. As heady as the season was for the club and Expos fans, it was a difficult one for Speier. An off-season back injury that occurred while weight-lifting forced him to miss time during spring training. Although he played on Opening Day and in the early part of the season, he spent most of July on the disabled list. He was also benched for most of September, even though the Expos had to play eight doubleheaders during the month because of early-season rainouts. In one stretch of three consecutive twin bills he played only one full game. Overall, he appeared in 113 contests and batted only .227 with 7 home runs and 26 RBIs.

Many people considered the Expos “the team of the ‘80s,” and as the decade got started, it seemed as if Chris Speier was going to be the team’s designated bench-warmer. His ongoing back problems contributed to an atrocious start in 1980, not only with the bat, but with the glove as well Expos manager Dick Williams benched him on April 29 when he was hitting just .184 and fielding poorly, with eight errors in his first 13 games. Speier made only one start over the next four weeks, but won his job back on May 26 when he got three hits in a 4-0 Expos win at Wrigley Field and robbed the Cubs’ Ivan de Jesus of a hit.

“I didn’t like it [the benching] but finally it helped me realize that there were certain things I had to do,” said Speier. “It gave me a good chance to look at my own approach.”15

Speier took full advantage of his introspection. Unlike 1979, he played regularly in September as the Expos battled the Phillies down to the last weekend of the season for the division title before the Phillies clinched it on the second-to-last day. His batting average shot up to .265, although he hit only one home run and had 35 RBIs.

One might have thought that Speier’s 1981 season was sponsored by the numbers two and five because he hit .225 with two home runs and 25 RBIs. This statistical coincidence reflected how odd the year was for everyone, as a mid-season player strike forced major league baseball to divide the campaign into two “halves,” with the winner of the first half playing the second-half champion in a special playoff.

The Expos and Phillies faced off in the National League East. As he did in 1971, Speier played spectacularly in the clutch against Philadelphia, going 6-for-15 ; at one point he got on base seven consecutive times. The Expos defeated the Phillies in five games to advance to the National League Championship against the Dodgers. Unfortunately he was stricken with the “can’t-hit-itis” that plagued the rest of the team against Los Angeles – the entire club hit only .215 with one home run and eight RBIs in five games – and made only three hits in 16 at-bats (.188).

The team’s anemic(.246) hitting in 1981 prompted management to hire former Phillies hitting coach Billy DeMars for 1982 . Speier said that DeMars helped him from the start of spring training.. His average rose to .257, but it was his RBI total that stood out, as he had 60 ribbies that year, his highest total since 1975. He also hit seven home runs.

On June 14, 1982, he pulled off the time-honored hidden-ball trick against his opposite number with the Cardinals, Ozzie Smith, at Busch Stadium. With Smith on second and one out, Willie McGee flied out to center fielder Andre Dawson who threw the ball back to Speier. Expos pitcher Bill Gullickson then looked at the plate in preparation of throwing the next pitch when Speier, ball still in glove, tagged a wandering Smith for the third out of the inning.

Smith had the last laugh, however. He went 1-for-2, stole two bases and made the pivot on the game-ending double play, standing his ground even though Tim Wallach was barrelling in on him.

As rejuvenating as the 1982 season was, 1983 proved the opposite for Speier. A sprained elbow ligament put him on the disabled list in late May. In August, his playing time was reduced when the Expos called up shortstop Angel Salazar from Class AAA and traded for second baseman Manny Trillo, which prompted the team to move Doug Flynn from second to shortstop. Speier played in only 88 games that season, again batting .257, but with only two home runs and 22 RBIs.

Speier had already seen this scenario in San Francisco, and when his playing time in 1984 was limited to 25 games and his average mired at .150, it was hardly a surprise when the Expos traded him to St. Louis on July 1, where he didn’t count on much playing time behind Smith. As fate would have it, Smith injured his wrist on July 14 when Ed Whitson of the San Diego Padres hit him with a pitch. Speier filled in until Oz returned on August 20, then was traded to the Minnesota Twins, for whom he appeared in 12 games.

It’s fair to speculate that the reduction in Speier’s playing time and the arrival of Bill Virdon as Expos manager was not just coincidental. “I always thought that I was getting the shaft in Montreal,” he said. “A lot of times you aren’t given another opportunity.”16

A more telling comment was offered by 10-year-old Justin Speier. “I’m going to miss all my friends, the house and the school,” he said when asked about leaving his home in St. Adele. “I’m not going to miss Bill Virdon.”17

Speier signed with the Chicago Cubs as a free agent the day before the 1985 season opened. His career revived a bit, as he played in 106 games and batted .243 with four home runs and 24 RBIs. What distinguished this season from previous campaigns was his versatility. He played primarily at shortstop (58 games) but he also played at third in more games (31) than he had in his entire career (25).

Maybe playing third base agreed with him. In 1986 he played third base more (53 games) than he did shortstop (23 games) and batted .284, the highest batting average of his career, albeit in 155 at-bats. He also had six home runs and 23 runs batted in.

Those numbers didn’t induce the Cubs to sign him for 1987, so Speier inked a one-year contract with the Giants. He then proved that you can go home again by playing in 111 games splitting time between second, third and short. He also hit his first grand slam in 15 years in an 10-6 win over St. Louis, then hit his second salami of the week four days later in a 9-4 win at Pittsburgh. This accomplishment was part of a very good year for both Speier and the Giants. They won the National League West, but lost the NLCS in seven games to the Cardinals. Speier contributed 11 home runs, tied for the second-highest total of his career, with 39 RBIs and a .249 batting average but went hitless in five at-bats during the playoffs.

Speier’s on-field career wound down after that. He played in 82 games in 1988 with three home runs and 18 RBIs, and had two ribbies and a .243 average in 44 at-bats in 1989. His back landed him on the disabled list three times that final season, and he was left off the team’s post-season roster as they made it to the World Series for the first time since 1962 (they were swept by the Oakland A’s). A respectable 19-year career was over.

Speier has had jobs with various organizations in baseball since retiring as a player, including the Athletics, Cubs and Reds. He also managed in the minors and won a World Series ring in 2001 as the third base coach for the Arizona Diamondbacks. As of 2015, he was a special assistant to Reds general manager Walt Jocketty.

Chris also had the privilege of seeing his son Justin reach the major leagues. Justin had a 12-year career as a relief pitcher with seven teams. He compiled a 35-33 won-lost record with 17 saves.

Last revised: August 15, 2021 (zp)

Sources

Contra Costa (California) Times

Attheplate.com

Baseball-reference.com

1980toppsbaseball.blogspot.com

Santa Cruz Sentinel

The Argus (Fremont, California)

The Expos in their Prime by Alain Usereau

Hitting for the Cycle, by Joseph G. Donner, SABR Research Journal archives

Ottawa Journal

Sports Illustrated

Cincinnatireds.com

Notes

1 “Giants’ Rookie Speier Reminiscent of Pee Wee,” The Gazette (Montreal), May 29, 1971.

2 The first pick, which belonged to the Senators, was career backup catcher Bill Fahey, who played 11 years for Washington/Texas, San Diego and Detroit.

3 Putt Powell, “Speier’s Heart Set for San Francisco,” Amarillo Globe-Times, July 23, 1970.

4 Jack Hanley, “’Ifs’ Give Giants New Look This Year, ” The Times, (San Mateo, California), March 22, 1971.

5 Joe Sargis, “Making Giants Go,” “Independent Journal,” (San Rafael, California) May 14, 1971.

6 Giants’ rookie Speier reminiscent of Pee Wee,” The Gazette (Montreal), May 29, 1971.

7 A strike at the beginning of the season prevented teams from playing a 162-game schedule.

8 Ralph Chatoian, “Giants’ Highlight Film Features Young Stars,” Daily Independent Journal (San Rafael, California), January 10, 1973.

9 Pat Putnam, “They’re Neither Too Old Nor Too Young,” Sports Illustrated, April 30, 1973.

10 They included Chris Arnold, Ed Goodson, Dave Kingman, Bruce Miller, Steve Ontiveros, and Mike Phillips.

11 In addition to Ontiveros and Speier, the Giants used Jack Clark, Goodson, Marc Hill, Miller and Phillips.

12 “Westrum Needs More Speiers,”DailyIndependent Journal,” April 30, 1975.

13 Ian MacDonald, “Expos trade of Foli for Speier forced by club’s pitching need,” The Gazette, April 28, 1977.

14 Ibid.

15 MacDonald, “Chris Speier back at short after month on the bench,” The Gazette, May 27, 1980.

16 “Green Paces Cards Pasty Braves, 8-5,” The Pantagraph, (Bloomington, Illinois), August 20, 1984.

17 Susan Schwartz, “Quebec scored big hit with Speier family,” The Gazette, July 7, 1984.

Full Name

Chris Edward Speier

Born

June 28, 1950 at Alameda, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.