Andre Dawson

Determination made Andre Dawson a great player — determination to come back after more than a dozen knee operations, determination to show baseball how overlooked he was during his first 11 years playing north of the border, determination to become one of the most well-rounded players in the game’s history. Andre Dawson showed that determination on his face with a menacing scowl at the plate and was one of baseball’s true five-tool players. He could run, hit, hit with power, field, and throw and was among baseball’s best in each category.

Determination made Andre Dawson a great player — determination to come back after more than a dozen knee operations, determination to show baseball how overlooked he was during his first 11 years playing north of the border, determination to become one of the most well-rounded players in the game’s history. Andre Dawson showed that determination on his face with a menacing scowl at the plate and was one of baseball’s true five-tool players. He could run, hit, hit with power, field, and throw and was among baseball’s best in each category.

Dawson was born on July 10, 1954, in Miami, Florida, and was the oldest of eight children. He played his first Little League game in 1963, showing his athleticism at a young age and regularly playing with kids who were several years older. It was there he received his nickname, “The Hawk,” by his uncle because he had a hawk eye at the plate. But Dawson also loved other sports. He played football for Southwest Miami High School, and in 1971, severely injured his knee.

“A North Miami receiver blocked one of our corner backs into me, and his helmet struck my left knee,” Dawson wrote in his autobiography, “I went down immediately. Rolling back and forth on the field in pain, I knew that I was seriously hurt. When I tried to stand, I couldn’t. My leg wobbled like Jell-O. The trainers insisted I had only strained a ligament in my knee, and they sent me home.” Unfortunately for Dawson, it was much worse.

“Later that night I started to get a burning sensation in my leg and found it impossible to sleep. The next morning my mother took me to the hospital. An orthopedic surgeon diagnosed me as suffering from torn cartilage and ligaments.” He would have to have surgery the next morning. It was the first of many knee surgeries for Dawson.

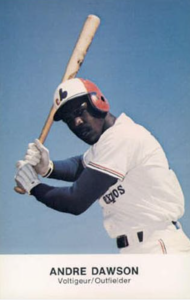

After he recovered from his first surgery, Dawson narrowed his athletic focus to baseball. He made the baseball team at Florida A&M University and was drafted in the eleventh round by the Montreal Expos in 1975. After one year in Lethbridge, Alberta, and most of a season split between Quebec (Double-A) and Denver (Triple-A), Dawson was a September 11 call-up in 1976.

Dawson’s first full season in the majors was in 1977, and he made the most of it in Montreal’s center field. Dawson batted .282 with 19 home runs, 65 RBIs and 21 stolen bases. He tallied 148 hits and 64 runs scored and won the National League Rookie of the Year. He married his wife, Vanessa, in 1978. That year, his batting average fell to .253, but he clubbed 25 home runs and drove in 72 runs. He was hit by 12 pitches to lead the league in that painful category. In 1979, he batted .275, with 25 HRs, and 92 RBIs.

Dawson opened the new decade with his best performance yet. In 1980, he had his first season batting over .300 (.308). He also had 17 home runs, 96 runs scored, 87 RBIs and 34 stolen bases. Dawson won his first of eight Gold Glove Awards that year and his first Silver Slugger Award as well. It was the most well-rounded season in Dawson’s young career, and he was out to prove it wasn’t a fluke.

In 1981, Dawson batted .302 in a season split by a player strike. He earned his second Gold Glove and Silver Slugger and finished second in the National League MVP voting behind Philadelphia third baseman Mike Schmidt. He reached 24 home runs and 26 stolen bases in the shortened season, his third 20-20 season, and was named an All-Star for the first time. But most importantly, Dawson led the Expos to the National League playoffs. In the National League Division Series against the Philadelphia Phillies, Dawson batted .300 with two stolen bases and a run scored to help Montreal win in five games. Next up was the Los Angeles Dodgers — Dawson’s favorite team growing up. Dawson’s average slipped to .150 as the Dodgers won the pennant in five games.

Determined to continue his strong play and get the Expos back to the playoffs in 1982, Dawson completed his third consecutive season in winning a Gold Glove, Silver Slugger, and batting .301. He earned his second All-Star appearance, but the Expos missed out on the playoffs. In fact, the Expos would never make the playoffs again.

In 1983, Dawson had perhaps his best season. At least his most well rounded. He led the National League with 189 hits and 341 total bases. He also batted .299 with 32 home runs and 113 RBIs — the first time he reached either the 30 homer or 100 RBI plateau. He also scored 104 runs and stole 25 bases and again was named an All-Star and won Gold Glove and Silver Slugger honors. He was named The Sporting News Player of the Year, but once again, he finished second in the NL MVP voting, this time to Atlanta center fielder Dale Murphy.

Dawson had his first down year in 1984. The artificial turf in Montreal’s Olympic Stadium was making his knees worse. It had begun to show on the field. He played in just 138 games and batted .248. He had moved to right field so he would have less ground to cover on the turf and won a Gold Glove in his first season in right, showing that it was his knees that were struggling, not his ability. In 1985, Dawson improved to .255 but still only played 139 games. He hit three home runs in a game at Wrigley Field near the end of the season.

Ten years in the majors was starting to show. Dawson turned 32 in the middle of the 1986 season and based on the two seasons of struggle he had in 1984-85, many thought The Hawk’s career was on the downslide. But in 1986, without playing a full season (130 games), and going on the disabled list for the first time in his career with a hamstring injury, his hitting improved to .284 with 20 home runs in the final year of his contract.

Dawson was hoping his resurgence would lead to a superstar contract that he thought he deserved. After all, he had finished second in the MVP voting twice, won the Rookie of the Year Award and six Gold Glove Awards during the past ten years with the Expos. He set Montreal’s records for career games, at bats, runs, hits, doubles, triples, home runs, runs batted in, extra base hits, total bases and steals (all have been broken).

So after a strong 1986 season, Dawson was the greatest player in the history of the franchise and still one of the top outfielders in baseball. In today’s free-agent market, Dawson, as the prize free agent of the off-season, would have been looking at offers of more than $10 million a season. But baseball was different in 1987. Dawson received no offers from other teams. The only offer came from Montreal and included a pay cut, which Dawson has continuously referred to as “insulting.” The same team that went out and made moves to get players like Tony Perez and Dave Cash 10 years before, was trying to low-ball the best player in franchise history.

Dawson and his agent Dick Moss went on the offensive, inquiring about his services to other teams. What they didn’t know yet was that the baseball owners were colluding to try and stop free agency. As union head Marvin Miller said, “It was an agreement not to improve your team.” The owners would be found guilty of collusion and be forced to pay the players in lost wages. But that wouldn’t come until later. Meanwhile, Dawson found himself in a dilemma. He had grown up with the Montreal Expos, playing his entire career with the club. But they wouldn’t really budge on the poor offer since no other teams made Dawson an offer. He also wanted to play somewhere that had natural grass in the outfield (Dawson had undergone eight knee surgeries by this point) and somewhere where he could get the proper respect as a superstar.

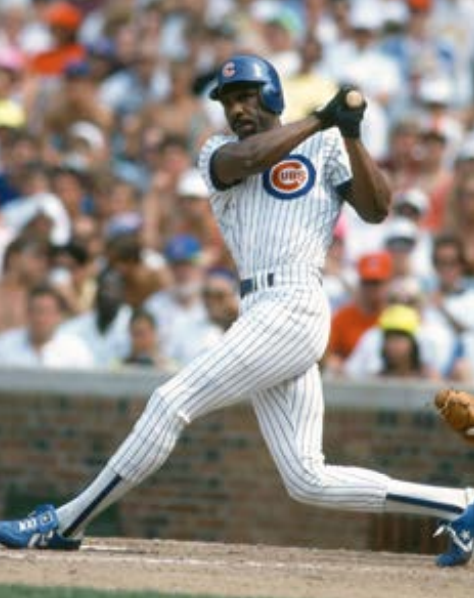

Dawson narrowed his prospective teams down to a handful. Then finally he and Moss decided that playing for the Chicago Cubs would be the best fit for him as well as the team. Dawson and Moss went to the Cubs’ spring training facility in Arizona with a blank contract and told them to make whatever offer they wanted and he would sign. “This is no joke,” Moss told Chicago General Manager Dallas Green. “Andre really wants to play for the Cubs, and he will do so for any salary that is fair. That is why we left that section of the contract blank. Feel free to fill in your own numbers.” Within 24 hours, he was a Chicago Cub, though he would actually be paid less than he would have been in Montreal. But to play in Chicago, where Dawson had always performed well, and play on natural grass, it was an improvement. If the Cubs had not accepted the offer, Dawson might have signed with another team or even gone to play in Japan, which his wife Vanessa was wary of, unless he changed his mind and re-signed with the Expos.

“I can’t describe for you the feeling of elation I experienced as we walked out of Green’s office that afternoon,” Dawson wrote in his autobiography. “I had taken back control of my own life.” The Chicago Cubs made out like bandits, getting Dawson for far less than his market value. With both the team and Dawson happy, The Hawk was eager to prove to the Expos what they would be missing and to the Cubs what they had gained. Dawson would not only turn in the best season of his career, but one of the best offensive seasons of the previous 20 years.

Dawson had always been able to hit for power, but playing healthy and at Wrigley Field helped his power numbers reach new heights with his new team. He dedicated the season to his grandmother, Eunice Taylor, who died early in 1987. It motivated him to make it his best. He hit for the cycle on April 29. Things were going great. The fans embraced Dawson immediately, especially the “Bleacher Bums” in right field.

Dawson had always been able to hit for power, but playing healthy and at Wrigley Field helped his power numbers reach new heights with his new team. He dedicated the season to his grandmother, Eunice Taylor, who died early in 1987. It motivated him to make it his best. He hit for the cycle on April 29. Things were going great. The fans embraced Dawson immediately, especially the “Bleacher Bums” in right field.

No opposing team felt his wrath more than the San Diego Padres. As the Cubs hosted the Padres for a series in July, Dawson had already hit six home runs off manager Larry Bowa’s team. Eric Show was San Diego’s best pitcher, and Dawson had not fared well against him during his career in Montreal, hitting a measly .091. Dawson turned that tide in 1987. He hit a home run off Show in San Diego early in the season, then knocked Show out of the game with a base hit. On July 7 at Wrigley Field, Dawson belted a home run off Show in his first at bat. Show was furious, and in Dawson’s next at bat, he hit Dawson in the face with a pitch. “With the brand of sinking fastball that Show throws, it is often impossible to pick it up until it’s too late,” Dawson said. “That is what happened with the first pitch in my second at-bat. I never really saw the ball leave his hand. The next thing I knew, I was lying face down in the dirt. My head was throbbing with the impact of a thousand sonic booms.”

Meanwhile, Cubs pitcher Rick Sutcliffe had immediately charged out of the dugout to go after Show. San Diego first baseman John Kruk caught Sutcliffe before he reached Show, but it took more than Kruk to restrain Sutcliffe. While Dawson was down, he heard teammate Leon Durham say, “It’s a shame we’re going through this at all. We’re supposed to be out here enjoying the game. But look at the guy’s face.” After lying in and out of consciousness for a few minutes, Dawson got up and went after Show, prompting Show’s ejection from the game. He ran into the dugout just before Dawson could get there as Tony Gwynn restrained him. “My first thought was revenge at the time,” Dawson said.

Dawson was rushed to Northwest Hospital and underwent 21 stitches to close the wound and had a plastic surgeon work on most of it from the inside. Dawson missed a few games but was back for the All-Star Game. It was his first trip in four years and first as a Chicago Cub.

The second half picked right up where the first left off for Dawson. On August 1, playing on a hot and humid day, Dawson hit three home runs in a game against the Phillies. “I didn’t even think I was going to make it past the fifth inning,” he said. “The fans started getting into it and I hit a third home run. It is just unbelievable considering the circumstances [heat] when you can barely get from the dugout to the outfield.” But unfortunately, despite Dawson’s heroics, the Cubs finished in last place. It was bittersweet for Dawson, who had enjoyed his best season, leading the National League with 49 home runs, 137 RBIs and 353 total bases while batting .287. He also won his first Gold Glove and Silver Slugger as a Cub. But Dawson’s biggest honor came when he outdistanced St. Louis shortstop Ozzie Smith 269-193 for the MVP award. Dawson had 11 first-place votes to Smith’s nine and was the first player to win the MVP while playing for a last-place team. It didn’t matter if his team was in first or last place, Dawson played the game the same way. “I am very intense when I am out on the playing field,” he told interviewer John Calloway in 1987. “I play the game as hard as I am capable of playing and try not to let up.”

In 1988, Dawson’s power numbers dropped to 24 home runs and 79 RBIs, but he surged to a .303 batting average, made the All-Star team and won his eighth and final Gold Glove. What was more important was the Cubs improved to fourth place and were showing signs of a turnaround. Dawson was one of the key figures in the turnaround, along with veteran second baseman Ryne Sandberg and pitcher Rick Sutcliffe, as well as youngsters Shawon Dunston at shortstop and Greg Maddux on the mound.

Things quickly came together for the Cubs in 1989 under manager Don Zimmer. Mark Grace had taken over for Durham at first and batted .314 while the Cubs started three rookies: catcher Damon Berryhill and outfielders Jerome Walton and Dwight Smith. Walton batted .293 and was named Rookie of the Year. Dawson, limited to 118 games slugged 24 home runs and knocked in 77, though he did reach the career marks of 300 home runs and 2,000 hits in 1989. He reached both milestones the year his first child, Darius, was born. It was enough to help the Cubs win 90 games and make the playoffs. Dawson struggled at 2 for 19 but drove in three runs in a five-game loss to the San Francisco Giants in the NLDS. It would be the last time Dawson ever reached the playoffs.

Dawson was finally healthy all season in 1990, in time for the birth of his daughter, Amber, and drove in 100 runs in 1990 and 1991, marking the only time in his career to accomplish the feat back-to-back. He slugged 27 and 31 home runs, respectively, as the new decade began, and played in his final two All-Star Games, including 1990’s at Wrigley Field and 1991’s at Toronto’s Skydome, where Dawson hit a home run off the glass windows of the centerfield restaurant against then-Red Sox pitcher Roger Clemens — more than 450 feet away. But after retuning from the All-Star break, the Cubs finished fourth. Dawson finished his Cubs career in 1992 with 22 home runs and 90 RBIs.

On December 9, 1992, Dawson signed as a free agent with the Boston Red Sox. It was a move to another hitter-friendly stadium in Fenway Park. It was also a move to the American League for the first time in his career, allowing the slugger to play the outfield and also give his knees a break by being the designated hitter from time to time. He was feeling strong and felt if he played a couple of more seasons he would reach 3,000 hits and 500 home runs. But Dawson tore more cartilage in his knee during the season and his age was starting to show. He hit just 13 home runs — one being the 400th of his career and contemplated retirement.

But on April 10, 1995, Dawson returned to the National League, joining the Florida Marlins. He was primarily a pinch-hitter for two seasons before retiring after the 1996 season with 438 home runs, 1,591 RBIs, 2,774 hits, 314 stolen bases, 1,373 runs scored. Dawson joins Barry Bonds and Willie Mays as the only Major League baseball players in history with more than 400 home runs and over 300 stolen bases. He also won eight Gold Gloves and was an eight-time All-Star. He joined the Florida Marlins’ front office as a special assistant.

Five years after he retired, Dawson made his first appearance on the writers’ ballot for the Baseball Hall of Fame. He garnered 45.3 percent of the vote — a good showing on a first ballot but a far cry from the 75 percent needed for election. But Dawson’s vote totals saw a steady rise and in 2010 — his ninth year on the ballot – Dawson received 77.9 percent of the vote and was the lone electee from the writers’ ballot to be enshrined. He joined manager Whitey Herzog and umpire Doug Harvey, who were elected by the Veterans Committee, in the Class of 2010.

“Now, I fully understand why it is so tough to get into the Hall of Fame,” Dawson said. “It is a very sacred Hall of Fame. It is a close-knit fraternity. That meant a lot…I think it is a process. They are not going to crowd the Hall. More than a couple of guys won’t get in without getting a magic number (like 500 home runs or 3,000 hits). It is not like the Football Hall of Fame where so many get in each year. There are guys who deserve to get in so it takes some time. I was just hoping it wouldn’t take too long that I wouldn’t enjoy it.”

He went into the Hall of Fame with a Montreal Expos cap (the Hall of Fame makes that decision) after 11 years there. His plaque also made special mention of his unsurpassed determination and revitalization after moving to the Cubs, where he hit 174 home runs in six years.

“I feel Montreal was a platform but Chicago catapulted me to that status,” Dawson said. “It got to the point where the numbers maybe look good enough to get in. I felt like I had gotten the best of what I could get out of my abilities.” His moving induction speech focused on the theme: “Love the game, and the game will love you back.” His website is andredawson8.com.

Last revised: April 30, 2011

Sources

Dawson, Andre with Tom Bird. Hawk. Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing House, 1994.

D’Addona, Dan. 2010 interview with Andre Dawson.

Calloway, John. 1987 video interview for “He’s a Hero.”

Baseball-Reference.com

Baseballhalloffame.org

Full Name

Andre Nolan Dawson

Born

July 10, 1954 at Miami, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.