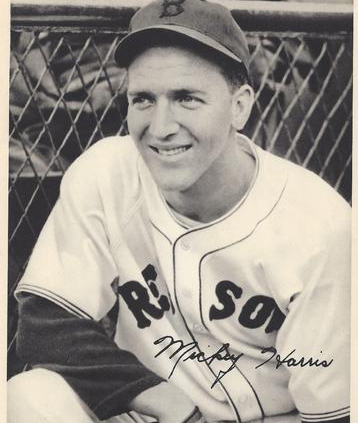

Mickey Harris

“Me a pop-off? Aw, that’s bunk.” — Mickey Harris, Boston Post, May 20, 1941

“Me a pop-off? Aw, that’s bunk.” — Mickey Harris, Boston Post, May 20, 1941

Mickey Harris is well known for an impressive amount of self-confidence and for posting a 17-9 record as one of the key components of the starting staff that carried the 1946 Boston Red Sox to their World Series showdown with the St. Louis Cardinals. After his impressive All-Star ’46 season, Mickey struggled to work through arm troubles that kept him from having any further success as a starting pitcher. He did, however, pitch well as a reliever for Bucky Harris’s Washington Senators in 1950 before he retired from baseball in 1953 at the age of 36.

Maurice Charles “Mickey” Harris was born on January 30, 1917, in the Belmont Park section of Queens Village, New York. He batted and threw left-handed, weighing in at 6 feet tall and 195 pounds during his playing years. His father, Maurice Sr., was himself a semipro infielder in the New York area. Mickey had a sister, Gertrude, and one brother, Henry.

It was in the infield that Mickey, as his father preferred to call him, got his start. At Public School 109, Jamaica Industrial High School, Harris found himself planted at first base, but when circumstances in a doubleheader required a new pitcher, Harris took the mound and never went back.

His semipro career began in the Queens-Nassau League, where he used the extra $5 to $10 a game the pitchers earned to supplement his day job of “spraying paraffin on milk containers for a dairy company.”1 In 1937, either through his own motivation or on the recommendation of his peers, the 19-year-old left-hander decided to pursue the next level, ending up at one of Bill Terry’s tryout camps for the New York Giants. In an attempt to launch some modicum of a professional career, Harris received permission to toss batting practice for the Giants, hoping to have his talent noticed. Unfortunately for Harris, the gambit did not pan out.

After Harris had spent two months working out with the Giants, his mother contacted the club’s front office in an effort to prevent her son from risking the possibility of losing his paying day job.2 The contact finally got Terry’s attention. Mickey was quoted in a May 20, 1941, Boston Post article: “He [Terry] told me that he hadn’t known I was jeopardizing my job in order to try out, and advised me to go back to work…. Naturally, I was hurt that nobody paid any attention to me for two months.”

Having had his immediate hopes of joining up with the major leaguers dashed against more realistic prospects, Harris continued to pitch in the Queens-Nassau League. His ability caught the eye of Red Sox scout and former big league umpire Jack Egan, who was helping to construct the new Boston farm system under the watchful eye of Farm Director Billy Evans.3 Egan scouted Harris from the sidelines, and saw the lefty serve up a game-winning grand slam. Harris later recounted the event for Boston sportswriter John Drohan:

“I’m pitching out on the Island for the Queens Alliance club. We’re playin’ the Belair Civics. The score is tied in the ninth when they load the bases on me. Then I throw my home run ball and everybody walks out on me.

“An old guy with gray hair comes up to me. When he asks me what I threw the batter, I think he’s a nosey fan. I told him a hook. He then asked me what my best pitch was. I told him my fastball. ‘Then why didn’t you throw it?’ he says.

“I got the red-ears anyways, so I says, ‘Well, if you can do any better, here’s my glove.’ But the old guy says, ‘Now, don’t lose your head. I’m Jack Egan and I scout for the Red Sox.’ I says, ‘Oh, yeah? I’m Lefty Grove.’ But he shows me credentials enough to convince me he’s the McCoy.”4

Harris ended up signing a contract for $100 per month and a bonus of $100. “I held out for an extra $50 bonus and got it,” he recalled.5 The contract was with the Red Sox affiliate in Clarksdale, Mississippi, in the Cotton States League. Egan initially attempted to skip the entry-level Clarksdale and place Harris in Little Rock of the Southern Association in 1938, but Harris was rejected.6 It was in the Little Rock spring training camp in 1938, however, that Harris heard his first words of encouragement from a member of a major league front office.7

In a training camp outing, nerves caused Harris to walk seven straight men. Out from under this cloud Billy Evans pulled a silver lining for the club’s young addition: “You were throwing the ball faster to the seventh man than you were to the first and that was what counted with me. You’re going to be all right.”8

Back pitching with Clarksdale for the 1938 season, Harris posted a 17-18 record. The following year, 1939, Harris found himself at the next level for the Scranton Miners in the Eastern League. There he greatly improved his control and improved his record to 17-4, shared the league lead in winning percentage with a mark of .810, and led in strikeouts with 148 in 184 innings pitched. As his control improved, so did his chances of making the big club in Boston.

Harris’s 1939 season is most remembered for helping solidify the cocky image he would carry with him for most of his playing days. In the 1939 Eastern League playoffs, Harris demonstrated the full force of his confidence. Wrote Hub Miller of Baseball Magazine:

“In the process of pacing Scranton to a pennant, the pride of Queens Village beat the Springfield club half a dozen times. But when the two rivals came together in the playoffs, Springfield won a close decision. Spencer Abbott, the Springfield manager and no shrinking violet, devoted the afternoon to giving Harris a verbal going over. Spencer used every word in a ballplayer’s book.

“Of course there wasn’t anything the young Harris could do about it. He had to stand out there and take it. But as he walked past the Springfield bench at the end of the game, he stopped and pointed a finger at Abbott, said: ‘You had your innings today, Abbott. But remember this. Next year you’ll still be down here, riding the same old busses and I’ll be in the big leagues. And every time I go through Springfield on the train I’ll stick my head out the window and wave to you.’”9

Indeed, Harris’s prophecy came to pass the following season. Early in 1940, Red Sox manager Joe Cronin decided to carry Harris, on the strength of his 17-4 season at Scranton, and on the show Harris put on at camp. “The Bosox pilot [Cronin] decided to have a look at the young southpaw and as the training period progressed, it was evident that Mickey had a live fastball, a sharp curve, and good control.”10 Still, Mickey’s overconfidence again got higher billing than his pitching talents, as he was overheard remarking in training camp, “The pitchers on this ballclub don’t look so hot. Winning twenty in the American League ought to be a cinch.” His image was further aided by an ill-concealed phone call home, in which he informed his parents that he would be replacing established Red Sox left-hander Fritz Ostermueller. Cronin cracked down on the fresh young southpaw for the remainder of camp, though Harris would come to have the last laugh, as he made the 1940 team.

Harris won his Red Sox debut in Fenway Park on April 23, 1940, against the Washington Senators and hurler Dutch Leonard, 7-2. He followed up with a win at Philadelphia over George Caster, 7-3. From there, he slumped, losing to Cleveland’s future Hall of Famer Bob Feller, and earning a no-decision against the Yankees’ Spud Chandler. The sudden drop-off stemmed from the most rookie of mistakes: Harris was tipping his pitches.11 Cronin shipped Harris back to the Scranton Miners in July; in his first major league stint, he’d posted a 4-2 record. As if to demonstrate to the skipper that his decision was ill-informed, Harris went on to post an Eastern League-leading ERA of 2.25.

Harris’s first full season came the following year, in 1941. Harris himself acknowledged early in the spring that he had been unprepared for a full season the previous year:

“My trouble last season?” remarked Harris, “That’s easy to answer.… In one word. Inexperience! I wasn’t ready.…

“I knew from the outset, even after winning those early games, that I needed more seasoning. Joe (Cronin) wanted me to throw overhead, because he felt it was my best pitch, and I felt the same way myself. Then from lack of experience, I found myself serving up too many fat pitches, like the day in St. Louis when they hit three homers off me.

“Yes, I knew my own faults and defects, and I’m sure that Cronin did the right thing sending me to Scranton. There I worked regularly, improved my overhead delivery and won 10 out of 15 games.…

“I’m frank to admit that I still have a lot to learn, but I know that I’m much better equipped right now than a year ago this month, and I sure hope I stay with the Sox this time.”12

Harris did remain in Boston for the entire 1941 campaign. He had matured enough to finish the year with a mark of eight wins and 14 losses, and even managed to be selected for the 1941 All-Star team, where he witnessed Ted Williams’ historic game-winning home run to right field at Briggs Stadium in Detroit. Still, the excitement of his debut season was overshadowed by the onset of World War II.

In May 1941, Harris was classified 1A by his draft board in Queens, available for unrestricted military service. There were enough volunteer student reclassifications, so Mickey was assured that he would not likely be summoned until that fall. His brother, Henry, offered to serve in Mickey’s stead in attempt to help along the fledgling major-league career, but “[t]he Army wouldn’t buy the deal and so Mickey lost some of his best baseball years.”13

On October 14, 1941, a month after his originally anticipated draft date, Harris was called into active service as Private Maurice Harris, 83rd CAAA (Coast Artillery Anti-Aircraft) at Fort Eustis, Virginia. Harris was stationed in the Panama Canal Zone, far from the concerts of Europe and the Pacific, and seemed to take his service requirements in stride. Said Harris to an unidentified journalist that November, “I’m still young and I’ll be back.”

Harris maintained his form by pitching for the Balboa Brewers in the Panama Canal Department Army League. His professional experience held him head and shoulders above most of the competition, as Harris led his Brewers to the Canal Zone League championship in 1942. To cap it off, Mickey attained the highest pitching honor in baseball, tossing a perfect game. On April 12, 1942, he retired all 27 batters of the Canal Zone All-Stars on only 67 pitches, striking out five, in a 9-0 victory for Balboa. Said Harris, “The greatest thrill I ever got in baseball came to me in the Army, when I pitched that perfect game in Balboa. I got more kick out of that than I did out of winning my first professional game, or even winning my first full game with the Red Sox.”14

Unfortunately, Harris injured his pitching arm in 1943, and was unable to help the Brewers repeat as Canal Zone League champions. Still, he managed to help the Brewers regain their top spot in 1944, and set a Canal League single-game strikeout record by whiffing 20 hitters on March 27, 1945.

Additionally, the 26-year-old Harris married Dorothy Elizabeth Baumann in St. Mary’s Catholic Church in the Canal Zone on August 6, 1944. They had three boys: Richard, William, and Kevin.

Mickey confidently returned from the Army after his heroics in the Canal Zone League. Crowed Harris, “I’ll win 25 this year. Yeah, I know that I wasn’t facing Joe DiMaggio, Charlie Keller, Jeff Heath, Lou Boudreau, and a lot of other big league clouters down there but if a pitcher has control with a good amount of stuff, he can win in fast company. When I went into the Army, lack of control bothered me. I have that now and I’m just telling you that I’ll win 25. Check with me next September 30.”15

Upon returning from his time in the military, Mickey found himself an integral part of the rotation that helped carry the Red Sox to their first World Series appearance since 1918. Although he didn’t end up reaching his 25-win prediction, Harris did manage to win his first seven starts of the ’46 campaign en route to a 17-9 season record. He was unable, however, to come through when it counted most, losing both of his World Series starts to the St. Louis Cardinals.

Harris pitched Games Two and Six, losing to St. Louis lefty Harry Brecheen in both games. Although the final score in Game Two was 3-0, Harris himself was responsible for only one of the runs. Mickey bore more responsibility in Game Six, the Red Sox losing 4-1, handing over three Cardinal runs in the third inning. The real culprit in both losses was a Boston lineup unable to push across any runs.

In addition to being his best season, 1946 would turn out to be the only season in which Harris would win 10 games or more. The two closing World Series losses marked the beginning of the end for Harris’s career. In 1947 his playing time was limited to 52 innings as the result of arm troubles that Harris claimed originated during a spring training start against the Cincinnati Reds.16 In 1948, Harris threw 113 2/3 innings but managed only a 7-10 record. A healthier Harris started the 1949 campaign, but after posting only two wins in 37 2/3 innings for Joe McCarthy’s Red Sox, he and outfielder Sam Mele were shipped to the Washington Senators for right-hander Walt Masterson.

In Washington the early returns on Harris were equally disappointing. He wrapped up 1949 as a starter for the Senators but managed only two more wins against 12 losses for the capital club, continuing the downward trend. In 1950, however, Mickey’s career picked up some unexpected life.

The Washington manager was none other than Bucky Harris, the man responsible for converting Yankee hurler Joe Page into a reliever. During spring training, Bucky reportedly walked up to Mickey and said, “Look, you’ve always been a starting pitcher. From now on, you’re a relief pitcher.” Bucky’s explanation was simple: “The guy’s got the temperament.… He’s cocky and confident. He’s the kind of guy who loves a fight and loves to show how he can get out of trouble. He’s got stuff and he’s been around the league for a long time. And he’s never going to do me much good as a starter. That’s for sure.”17

By August, Bucky knew his decision to convert Mickey had been a success: “That man has saved at least 15 ball games for me,” he told a Boston sportswriter. “He’s pitched in maybe 35 or 40. Sometimes, if my pitchers are going well, I don’t use him for a week, and sometimes I need him every day for a week. It doesn’t make any difference what I ask him to do. He does it, and that’s what counts. You know what? With Page having a bum year, this guy’s the best relief pitcher in the American league. Outside of that Jim Konstanty pitcher over in the other league, he’s the best relief pitcher in baseball.”18

As it turned out, Harris did indeed save 15 games in 1950, to lead the league. He also led the league in appearances, toeing the rubber in 53 games and finishing 43 of them. The key to his success as a reliever was to eliminate his weakness as a starter, namely, his inability to pitch more than a few good innings because of his arm troubles.19 Add a “newly developed slider pitch,”20 and Harris found some late life in his new home.

He had a mediocre season on a mediocre team in 1951; Washington’s most successful pitcher was Connie Marrero, with 11 wins. His career in Washington lasted one inning longer, and eight days after the 1952 season began, the Cleveland Indians purchased Harris’s contract from the Senators for $10,000. At 35 years old, Harris was on his way to his third major league club. His stay in Cleveland would be even shorter than in Washington. After tossing 46 innings of relief for the Tribe, Harris found himself placed on waivers at the close of the season. When no claims were submitted, Mickey received his unconditional release on March 27, 1953. With that, his career in professional baseball came to a close, as Mickey announced his retirement that spring.

“I figured I might have one or possibly two years left in the majors,” said Mickey, “and I concluded that I’d be better off to get out while I’m still young and healthy.”21

After his baseball career ended, Mickey held jobs as a car salesman in North Cambridge, Massachusetts, as the Western New York salesman for AMF bowling equipment, and as a maintenance worker for Holy Sepulchre Cemetery and Alexander Hamilton Insurance Company. Both maintenance positions were held in his home of Farmington, Michigan, where he had lived for 15 years.22

Mickey Harris died of a heart attack suffered while bowling on April 15, 1971. He was 54 years old.

Last updated: July 31, 2020.

Note

This biography originally appeared in the book Spahn, Sain, and Teddy Ballgame: Boston’s (almost) Perfect Baseball Summer of 1948, edited by Bill Nowlin and published by Rounder Books in 2008.

Notes

1. Shirley Povich, “Call for ‘Mr. Trouble!’” Baseball Digest (September 1950): 90.

2. Jack Malaney, “Harris, Red Sox Hurler, Labels ‘Pop-off’ Tag as Bunk, but Mickey’s No Mouse in Standing Up for His Rights,” Boston Post, May 20, 1941.

3. Peter Golenbock, Red Sox Nation (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2005) 101.

4. John Drohan, “Mickey Whistles While He Wins — So Does His Fastball.” Mickey Harris Player File, A. Bartlett Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

5. Summary of Mickey Harris’s signing and career, May 1971. Mickey Harris Player File.

6. Povich, “Call for ‘Mr. Trouble!’” 91.

7. Jack Malaney, “Red Hot Rookie of Red Sox: Harris Makes Grade on Hill in Hurry,” Boston Post, April 11, 1940.

8. Malaney, “Red Hot Rookie.”

9. Hub Miller, “The Whistler From Queens,” June 1947. Mickey Harris Player File. A. Bartlett Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

10. Malaney, “Harris Labels Tag as Bunk.”

11. Malaney, “Harris Labels Tag as Bunk.”

12. Fred Knight, “Hash, Harris Ready to Make Comebacks,” March 3 1941. Mickey Harris Player File, A. Bartlett Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

13. “Brother Bob Offered To Serve in Army.” Mickey Harris Player File, A. Bartlett Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

14. Tom Meany, “Mickey Harris Had Biggest Thrill in Canal Zone,” PM Syndicate, July 8, 1942.

15. Quote from Mickey Harris predicting success in 1946, March 1946. Mickey Harris Player File, A. Bartlett Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

16. Hy Hurwitz, “Mickey Harris Ordered Not to Touch Baseball for Next Two Weeks,” 26 June 1947. Mickey Harris Player File, A. Bartlett Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

17. Al Hirshberg, “ ‘Fireman’ Harris Haunts Red Sox” August 19, 1950. Mickey Harris Player File. A. Bartlett Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

18. Hirshberg, “Harris Haunts Red Sox,” August 19, 1950. Mickey Harris Player File.

19. Hirshberg, “Harris Haunts Red Sox,” August 19, 1950. Mickey Harris Player File.

20. Povich, “Call for ‘Mr. Trouble!’”

21. “Mickey Harris Quits Game,” 1953. Mickey Harris Player File.

22. “Maurice ‘Mickey’ Harris,” Farmington Observer, April 21, 1971, 14B.

Additional sources

Daniel, Dan. “Daniel’s Dope.” World Telegram, October 7, 1946.

Eberenz, Leo J. “3 in Row for Harris in Canal Zone Finals.” May 25, 1944. Mickey Harris Player File. A. Bartlett Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

Feldman, Chic. “Of Mickey Harris Late Pitching Idol.” The Scranton Tribune, April 24, 1971.

Grossman, Leigh, ed. The Red Sox Fan Handbook, Everything You Need to Know to be a Red Sox Fan or Marry One, Updated for 2005. Boston: Rounder Books, 2005.

“Harris, Red Sox, Is Rated Class 1A of Army Draft.” May 28, 1941. Mickey Harris Player File. A. Bartlett Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

“Harris, Ex-Red Sox, Married in Canal Zone.” United Press, August 7, 1944.

“Harris, Mele For Masterson.” United Press, June 13, 1949.

“Harris, Mickey C,” Detroit Free Press, April 17, 1971.

Photo Credit

The Topps Company

Full Name

Maurice Charles Harris

Born

January 30, 1917 at New York, NY (USA)

Died

April 15, 1971 at Farmington, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.