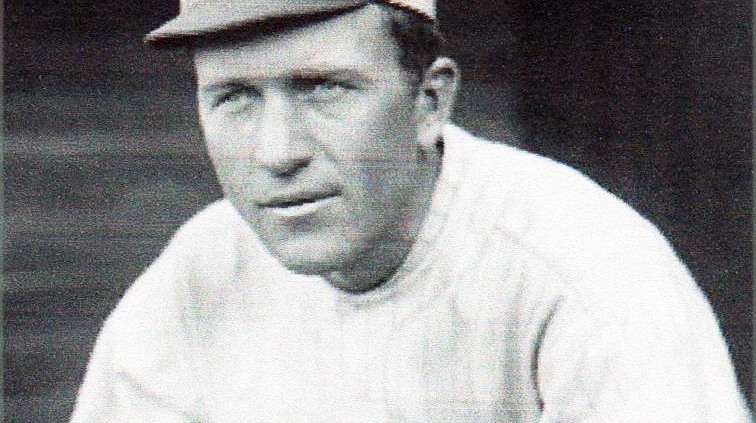

Bert Daniels

If, like beauty, the assessment of baseball talent lies in the eye of the beholder, the wide divergence of opinion on the abilities of Deadball Era outfielder Bert Daniels can be rationalized. Opinions, naturally, may differ. With our subject, whether it was his batting, defense, or base running, Daniels was both praised and derided — sometimes almost simultaneously — by contemporary commentators. A century later, the application of modern metrics consigns Daniels to the category of slightly below-average ballplayers. That rating, however, might have been a bit higher had Daniels reached the majors faster. His elevation was retarded because he was still playing college ball at age 27.

If, like beauty, the assessment of baseball talent lies in the eye of the beholder, the wide divergence of opinion on the abilities of Deadball Era outfielder Bert Daniels can be rationalized. Opinions, naturally, may differ. With our subject, whether it was his batting, defense, or base running, Daniels was both praised and derided — sometimes almost simultaneously — by contemporary commentators. A century later, the application of modern metrics consigns Daniels to the category of slightly below-average ballplayers. That rating, however, might have been a bit higher had Daniels reached the majors faster. His elevation was retarded because he was still playing college ball at age 27.

Whatever the toll on his baseball fortunes, Daniels doggedly pursued that education, financed by playing minor league ball under a laundry list of aliases. It enabled him to obtain the academic credentials necessary for entrance into the profession that occupied his post-baseball life: civil engineering. For more than 40 years, he alternated between government service, corporate employ, and private consulting. But during the 1930s, Daniels also returned to the game, enjoying a highly successful seven-spring run as a college baseball coach. Thereafter, he resumed his engineering responsibilities full time and stayed engaged in that work until just shortly before his death in 1958. The story of this eventful, multi-faceted life follows.

Bernard Elmer Daniels was born on October 31, 1882, in Danville, Illinois, a coal mining center located about 130 miles south of Chicago. Bert, as he was known throughout life,1 was the oldest of eight children. His father, John Randolph Daniels, was a carpenter-turned-factory foreman whose WASP ancestry traced back to colonial Virginia. His mother was Agnes Brigid (née Hughes), the Maryland-born daughter of Irish Catholic immigrants.

When Bert was still a youngster, the family relocated to Joliet, a larger city not far from Chicago. There he was educated through graduation from Joliet High School. Following high school, he found a job with the Chicago and Eastern Railroad Company and was assigned to the maintenance of way and engineering department. Some years later, Daniels recounted that “this gave me my first inclination to engineering work. I was pretty fair in mathematics and got along well in algebra.”2

Decent-sized (5-feet-11, and 175 lbs.),3 athletically gifted, and exceptionally fleet-footed, the youthful Daniels was a standout on local gridirons and diamonds. But with a professional football league still two decades away, he gravitated toward a career in baseball. A right-handed batter and thrower, Bert played outfield on various area semipro clubs, including the top-flight Joliet Standards. He entered the professional ranks in 1905, signing with the Albany Senators of the Class B New York State League.4 Before the season started, however, Daniels jumped to the Woodstock (Ontario) Maroons of the independent Canadian League.5 He served as an everyday outfielder, helping Woodstock (48-32, .600) cruise to the league title.

Daniels made a belated start on attaining an advanced education that fall, enrolling in St. Thomas College, a liberal arts school located in Minneapolis.6 Enticed by former Woodstock teammates who were Villanova undergraduates, Daniels switched schools the following spring, joining them at the Philadelphia college. With school administrators looking the other way, he then became the Wildcats left fielder. Back home for the summer, Daniels resumed his professional career with the inelegantly named Jackson Convicts of the Class D Southern Michigan League, hitting .256 in 24 games. Then he jumped again, this time joining the Lancaster (Pennsylvania) Red Roses of the outlaw Tri-State League.7 This move precipitated Daniels’s suspension from Organized Baseball,8 but that was not a matter of immediate concern for him. Nevertheless, he adopted the name “Walsh” for the remainder of the season, the first of the numerous aliases that Daniels used during his minor league days.9 That fall, he returned to Villanova, where, in addition to attending class, he manned the left end position on the football team.

The 1907 baseball season brought more of the same. After playing spring ball at Villanova, Daniels joined the Kane (Pennsylvania) Mountaineers of the Class D Inter-State League. But with his name still on Organized Baseball’s ineligible list, he adopted the alias “Thomas Barrett.”10 When Kane disbanded in mid-July, Barrett moved on to the Waterbury Authors of the Class B Connecticut League. Manager Jim O’Rourke of the rival Bridgeport Orators, however, soon got wise to Barrett’s true identity and had him expelled from the circuit.11 Undaunted, Daniels, under the name “Tommy Bothwick,” finished the season playing for an independent pro club in nearby Manchester, Connecticut.12

Over the winter, Daniels abandoned Villanova to enter the University of Notre Dame, a force in college athletics situated in South Bend, Indiana. Here, his previous college experience more or less repeated itself. Notre Dame officials were not unmindful of the whiff of professionalism that attached to Daniels when he suited up for the baseball team. But the minor league aliases that he had adopted served their purpose, providing both him and school officials with deniability when needed. In addition to a generally permissive attitude when it came to ND athletes — any number of whom were charged with professionalism during Daniels’s stay in South Bend13 — Notre Dame administrators were likely impressed by the fact that Daniels was a bona fide, class-attending student, serious about earning a degree. Nor did it hurt that he was paying his own way through school, albeit via the minor league salaries that he was obliged to conceal.14 Whatever the case, first baseman Daniels quickly became an important cog in a powerhouse Notre Dame lineup that included future major leaguers Jean Dubuc, George Cutshaw, Red Kelly, and Frank Scanlan. By the end of the 1908 campaign, the ND nine was the class of the Midwest, having posted a gaudy 20-1 (.952) record.

Daniels did not fare as well with Organized Baseball. Earlier that year his petition for reinstatement had been denied by the National Commission on jurisdictional grounds. Because Daniels was not a major leaguer, the commission ruled that the proper venue for his petition was the National Association of Minor League Clubs, the overseer of minor league baseball.15 This rejection required Daniels to devise a new alias when he returned to the pro ranks in the summer. As “Bert Berger” he played outfield for the league-leading (34-16, .680) Allentown (Pennsylvania) club in the independent Atlantic League.16

Given his foot speed, athleticism, and prior gridiron experience, a reluctant Daniels was induced to try out for the Notre Dame football team when he returned to campus that fall.17 He subsequently played halfback in intra-squad scrimmages.18 However, there is no evidence that Daniels ever saw any intercollegiate football action during his time at ND. Instead, he stuck to his studies and baseball. In spring 1909, his college eligibility was briefly placed under scrutiny by school officials,19 but he was cleared to play before the campaign began. Stationed again at first base, he batted .290 for a relatively disappointing 13-5-1 (.722) Notre Dame nine.20 At season’s end, he was elected team captain for 1910.21 But as it turned out, his time in South Bend had reached its end.

During that summer, Daniels returned to Pennsylvania to play for the Altoona Mountaineers of the now-recognized Class B Tri-State League. With his name still on the ineligible list, he adopted a new alias for the 1909 season: Bert Ayres.22 Despite getting a late start with his new club, he impressed. In 52 games, he batted .335, attracting the attention of major league scouts in the process. Meanwhile, Daniels had somehow managed to regain his eligibility to play in Organized Baseball. Before the season was up, his contract rights were acquired by the New York Highlanders, perennial American League also-rans.23 Highlander scout Arthur Irwin, a former major league infielder and manager, was an ardent Daniels admirer. “He is a wonderful hitter, base runner, and fielder,” exclaimed Irwin, likening Daniels to no less than Ty Cobb.24

Daniels had resolved to try to make a livelihood in professional baseball. But he also realized that he would need credentials for a post-baseball occupation. To that end, and with a college diploma finally within reach, he enrolled in Bucknell University, a Pennsylvania school renowned for its engineering program, at the close of the 1909 season.25 While there, he joined the Sigma Chi fraternity and kept in baseball shape by playing first base for the university varsity the following spring, rather than reporting to Highlanders’ spring camp.26 In June 1910, one important career goal was thus achieved. By then 27 years old, Daniels was awarded his coveted Bachelor of Science degree in civil engineering by Bucknell. He then reported to the Highlanders.

Bert Daniels made his major league debut on June 25, 1910, pinch-running for Hal Chase and then taking over at first base in the ninth inning of a 7-4 New York road victory over the Washington Senators. At the time, third base was a problem for Highlanders manager George Stallings, with regular Jimmy Austin temporarily laid up. Despite having virtually no experience at the position, the newly arrived Daniels was dispatched to the hot corner. In six games there, he fielded tolerably (.917 FA) while holding his own at the plate. Soon thereafter, Daniels supplanted veteran Charlie Hemphill in the New York outfield.

Despite getting into only 95 games, Daniels led the Highlanders in stolen bases (41) and placed second in runs scored (68) to right fielder Harry Wolter. Contributing to a healthy .356 on base percentage was his knack for getting hit by pitches. His modus operandi was to crowd the plate and make little effort to avoid tight pitches.27 The result: an American League-leading 16 HBP, the first of three times that he would pace the junior circuit in that category. His other rookie stats — .253 BA, with only 22 extra-base hits including a lone home run — were pedestrian. Still, the newcomer had made a good enough impression and appeared to have a future with a club seemingly on the rise, at last. New York finished in a tie for second place (88-66, .571).

Over the winter, a pall was cast on Daniels’s prospects by New York’s acquisition of veteran outfielder Roy Hartzell.28 But Highlanders player-manager Hal Chase — the star first baseman had taken the club reins late the previous season — decided to install the versatile Hartzell at third instead and leave Daniels in place. As an everyday outfielder, mostly in center field, the second-year man seemed to establish himself as a major leaguer in 1911. In 131 games, he batted.286, solid for the Deadball Era, with 27 extra-base hits and 31 RBIs. He also stole 40 bases. Except for base thefts, however, his numbers did not match those of outfield mates Birdie Cree (.348/56 xbh/88 RBIs) or Harry Wolter (.304/36 xbh/36 RBIs). The outfield-capable Hartzell also posted better marks (.296/31 xbh/91 RBIs). Furthermore, New York slid to sixth place in AL final standings (76-76-1, .500). With changes doubtless in the offing for 1912, Daniels’s status with the club was insecure.

On Opening Day 1912, Daniels was the New York center fielder, getting a base hit off Boston’s Smoky Joe Wood in a 5-3 setback. Soon thereafter, it was widely reported that he had been placed on waivers by new Highlanders manager Harry Wolverton.29 However, an injury that sidelined right fielder Wolter then afforded Daniels a reprieve. He took advantage of it, doing effective work in the leadoff spot and showing “better base running ability than any other of the Hilltop men.”30 The approval was not unanimous, though. For example, the Washington Herald asserted that “Bert Daniels is having an in-and-out season with the Highlanders. He has been playing with flashes of good and bad form.”31 Still, reviews of his play were mostly positive that season. A St. Louis newspaper offered this late-season encomium: “With his great fielding ability, Daniels is a star hitter. He is one of the most valuable ball players showing on any diamond.”32

In the service of a last-place (50-102-1, .329) New York club, Daniels posted numbers comparable to his previous season’s work: .274 BA, with 38 extra-base hits, and 37 stolen bases. He also again led the American League in HBP (18). With discharged manager Wolverton replaced by Frank Chance, the Peerless Leader who had led the Chicago Cubs to four recent National League crowns, a brighter future was predicted for both the ball club and for Daniels. Among his boosters was Detroit Tigers manager Hughie Jennings, who stated, “I have been expecting for two years to see Bert Daniels round into a star of the first magnitude [and] Chance is just the man to polish Daniels off.”33

Our subject, however, was hardly without critics. In a nationally syndicated offseason article, New York sportswriter Bill Macbeth classified a supposed Daniels asset — his base running — as a liability. “Bert Daniels should be a great base runner — but never has been,” Macbeth asserted. “Daniels came from the Tri-State League with a great reputation as a base runner. He never panned out in the big show because he always seemed to slide into instead of away from the ball. All a base guardian had to do was to block Bert and he was duck soup.”34 Daniels was also faulted for nullifying the large leads that he took by slow first steps when attempting to steal a base. “Let him learn to get away quickly and slide properly and he should be a ‘bear,’” wrote Macbeth.35 Daniels was reputedly the fastest man in major league baseball yet was thrown out stealing 20 times (35% of his theft attempts)] in 1912 — the only season for which caught stealing stats are currently available for him. Thus, the Macbeth critique appears to have some basis.36 In any event, it was not the only time that Daniels’s base running was found wanting in the press.37

While press commentators dissected his abilities, Daniels prepared for his post-baseball life by working that winter in the civil engineering department of the New York Central Railroad.38 With a fourth manager in four seasons to impress, however, the quiet, sober, and serious Daniels reported to New York Yankees spring camp in Bermuda that March in his customary tip-top physical condition.39 During camp, conflicting commentary about his playing abilities continued to surface. A Michigan newspaper described Daniels as “a sure master of flies”40 at about the same time that an Ohio sportswriter deemed him “a poor outfielder.”41 Comment on his batting also tended to conflict. One newspaper described him as “a highly respected batter”42 while another cited a “weakness at the bat” sufficient to likely keep him out of the everyday New York lineup.43

More important to Daniels, he got off to a good start with his new skipper. First-rate work in spring camp prompted manager Chance to install him at the top of the lineup as the 1913 season began, but Daniels did not hit well. Getting hit was another matter. In a June 20 clash with Washington, he was hit by a pitch his first three times at bat — by three different Senator pitchers.44 Several weeks later, he briefly interrupted his season’s work to take a bride, marrying 23-year-old New Jerseyite Alice Cooper. The birth of daughter Arlene (1918) and son Bert (1922) subsequently completed the Daniels family.

With his Yankees firmly ensconced in the AL basement (33-66, .333), manager Chance decided to shake up his roster. On August 9, he sent Daniels (and his meager .216 batting average), backup infielder Ezra Midkiff, and $12,000 to the Baltimore Orioles of the Class AA International League in return for hot-prospect shortstop Fritz Maisel.45 In the trade’s aftermath, a Jersey City paper observed that Daniels’s “greatest ability lay in his speed, but he did not know how to use it, for several slower men on the club were better base runners. He was a fast and fairly accurate outfielder, but his hitting was always weak.”46

In Baltimore, Daniels did little to bolster his chances for another major league shot. In 41 games, he batted a tepid .241 with only eight extra-base hits. Given another opportunity the following year, he turned it around. In 66 early-season games in 1914, he batted a robust .324, with 23 extra-base hits and 21 steals. But revitalizing his promotion prospects soon embroiled Daniels in inter-league controversy. First, he refused to accept a trade to the Louisville Colonels of the Class AA American Association, professing a determination to remain in the East.47 But outraged International League President Ed Barrow suspected that Daniels was actually stalling until arrangements were made for him to jump to the Baltimore Terrapins of the newly arrived Federal League.48 Terrapins president Carroll William Rasin promptly denied the charge, insisting that it was club policy to avoid contact with Orioles players in the interest of maintaining intra-city peace.49 Orioles club boss Jack Dunn thereupon terminated the imbroglio by selling the contract of Daniels — who was amenable to this transaction — to the Cincinnati Reds.50

Given a second major league life, Daniels got off well with his new club, batting a respectable .281 in his first 15 games in a Cincinnati uniform. Regrettably, he could not keep up that pace. By the close of the 1914 campaign, his batting average had sunk to a powerless .219 in 71 games, and he did not figure in second baseman- manager Buck Herzog’s plans for 1915. But Daniels was still wanted by the Louisville Colonels, who purchased his contract from the Reds in December.51

The sale brought the major league career of Bert Daniels to an end at age 32. In 526 games spread across five seasons, he posted a .255 batting average, with 121 extra-base hits but only five home runs. His ratio of strikeouts (224) to walks/HBP (275) was above the Deadball Era norm, as was his .349 on base percentage. Daniels stole 159 bases, but with complete caught stealing data unavailable, the cogency of criticism of his base running is difficult to assess. Although handicapped by a weak throwing arm, his superior range probably elevates him to the above-average category as a defensive outfielder. In the end, and being essentially a singles hitter a significant minus, Bert Daniels appears to rate as slightly below average for a 1910-1914 major leaguer.52

Daniels proved a useful acquisition for Louisville. Batting mostly in his familiar leadoff position, Bert batted .299 with a professional-career-high 112 runs scored for the fourth-place (78-72, .520) Colonels in 1915. He returned to Louisville the following season and was among American Association batting leaders when he fractured a fibula sliding during a late-June contest with the Kansas City Blues.53 Out of action for the next two months, Daniels finished with a .313 BA in 52 games. Later that fall, a syndicated news article provided this forlorn status update: “Bert Daniels, Hailed as Future Cobb, 34, Now Almost Forgotten.”54

Daniels suited up for Louisville again in 1917, but age and injury had taken their toll. In 137 games, he batted a soft .254 and seemed bent on retiring at season’s end. It therefore came as something of a surprise when the following April, he agreed to accept the post of player-manager of the St. Joseph (Missouri) Saints of the Class A Western League.55 By then, however, America was focused on the World War I effort, with many minor leagues shuttered for the duration. The Western League began the season as scheduled but ceased operation in early July. Before the shutdown, Daniels piloted St. Joseph to a seventh-place (30-38, .441) berth, contributing a .285 batting average in 54 games to the effort.56

Although he continued working as a civil engineer in the offseason, Daniels still wanted to play ball once hostilities ended. In April 1919, it was announced that he had signed with the Reading (Pennsylvania) Coal Barons of the International League.57 But he never reported. Instead, Daniels tended to his engineering work, playing an occasional semipro game on weekends. An urge to give it one last try, however, brought Daniels’s days in Organized Baseball to a close on a somewhat sour note. Signed by the New Haven (Connecticut) Indians of the Class A Eastern League for the 1921 season, he was again a no-show. Unforgiving New Haven management promptly suspended him and placed his name on OB’s ineligible list.58 The suspension was lifted, and his eligibility restored at season’s end, but Daniels was genuinely retired from baseball by that time.

During the 1920s, Daniels took up residence in New Jersey, living with his wife and children in various Newark suburbs and alternating between working for local government and doing private engineering consulting work. In 1931, he got back into the game, accepting the post of head baseball coach at Manhattan College.59 Taking over a squad that had gone 7-11 (.388) the previous year, he promptly transformed the Jaspers into a winner. Over the next seven springs, Manhattan registered an excellent record of 93-38-1 (.710). But in 1939, the press of engineering projects obliged Daniels to resign his coaching job.60

During World War II, Daniels worked for the federal government as an inspecting engineer for airfield and barracks projects. In 1950, he assumed the post of sanitary engineer for the Town of Cedar Grove, his place of residence since 1945. He added the duties of acting town building inspector a few years later.

By the time of his retirement in 1956, Daniels was suffering from coronary artery disease. While at home on June 6, 1958, he suffered a fatal heart attack.61 Bernard Elmer “Bert” Daniels was 75. Following a Requiem Mass said at St. Catherine of Siena Church, Cedar Grove, his remains were interred at Immaculate Conception Cemetery in nearby Montclair. Survivors included his widow, two children, three grandchildren, two sisters, and a brother.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

Sources for the biographical information imparted herein include the Bert Daniels file with two completed player questionnaires in the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York; US Census and other government records accessed via Ancestry.com; and various of the newspaper articles cited in the endnotes, particularly the informative “Daniels Shines for N.Y. Highlanders,” Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Patriot, August 11, 1910. Unless otherwise noted, stats have been taken from Baseball-Reference.

Notes

1 Daniels used his actual first name Bernard only rarely, customarily identifying himself as Bert E. Daniels. The TSN player contract card and 1958 obituary use of the first name Bertram for him was mistaken.

2 According to Daniels himself in “Daniels Shines with N.Y. Highlanders,” Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Patriot, August 11, 1910: 8, re-printing an article originally published in the New York Journal.

3 Per the posthumous player questionnaire completed by son Bert Daniels, Jr. Modern baseball authority lists Daniels as slightly smaller.

4 Same as above. See also, Joliet (Illinois) Evening Herald, September 14, 1905: 5, and April 23, 1905: 5.

5 Per “Daniels Shines,” above.

6 See “Personals and Newsy Notes,” Joliet Evening Herald, December 24, 1905.

7 Per “Baseball Notes,” Kalamazoo (Michigan) Gazette, July 24, 1906: 5, and confirmed by Daniels in “Daniels Shines,” above.

8 See “Barred from Organized Baseball,” Washington (DC) Evening Star, August 15, 1906: 9. See also, Brooklyn Standard Union, August 15, 1906: 8.

9 Per “Daniels Shines,” above.

10 The real Thomas Barrett was a Joliet schoolboy friend of Daniels.

11 Per “Daniels Shines,” above.

12 Same as above. The real Tommy Bothwick was a Joliet Standards teammate of Daniels.

13 Pitcher-outfielder Jean Dubuc and catcher Ray Scanlan were briefly withheld from action after being publicly accused of playing in the semipro Chicago City League until a perfunctory Notre Dame internal investigation cleared them. In an ironic twist, star Notre Dame cager Pete Vaughn was dogged by reports that he played professional baseball under the name Bert Daniels. See “Charge Vaughn Is Professional; Detroit A.C. Claims His Name Is Bert Daniels,” South Bend (Indiana) Tribune, February 15, 1909: 9. Vaughn, too, was later cleared by school officials.

14 Again, as explained by Daniels in “Daniels Shines,” above.

15 See “Daniels Case a Lesson,” Detroit Free Press, February 9, 1908: 13; “Bert Daniels Not Reinstated,” Baltimore Sun, February 9, 1908: 10.

16 “Daniels Shines,” above. Allentown’s ace pitcher was Frank Scanlan, a Notre Dame teammate who played under the name “Strauss.”

17 See “Thirty-Five Men Out for Practice,” South Bend Tribune, September 22, 1908: 9.

18 See “Crowd to Witness Notre Dame Plays,” South Bend Tribune, November 5, 1908: 12; “Daniels Joins Eleven To-Day,” South Bend Tribune, November 3, 1908: 9.

19 See “Bert Daniels Still Under Ban,” South Bend Tribune, April 3, 1909: 13; “Around the Circuit,” Evansville (Indiana) Courier, April 2, 1909: 11.

20 Per stats published in “Season a Success at Notre Dame,” South Bend Tribune, June 12, 1909: 12.

21 See “Bert Daniels to Lead 1910 Varsity,” South Bend Tribune, June 11, 1909: 14.

22 See again, “Daniels Shines,” above. Regarding his latest alias, Daniels declined to identify its source but cryptically told his interviewer that “after I am married I might tell you.”

23 As noted in Sporting Life, September 11, 1909: 2. It was later revealed that New York acquired Daniels’ contract for the piddling sum of $250, plus a minor league catcher. See “Bert Daniels Cheapest Investment in Leagues,” Joliet Evening Herald, August 16, 1910: 6.

24 See “Kind Words for Daniels,” Harrisburg Patriot, February 8, 1910: 10.

25 “Daniels Shines,” above.

26 See “Daniels Reports in June,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, January 23, 1910: 17.

27 As recalled years later by former major league infielder Ernie Johnson. See L.H. Gregory, “Gregory’s Sport Gossip,” (Portland) Oregonian, June 8, 1926: 15.

28 See “Hartzell Has Chance to Earn Regular Berth in the Outfield,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 3, 1911: 15.

29 The waiver report, uncontradicted by manager Wolverton, was published in the New York Evening World, April 27, 1912: 7; Washington Evening Star, April 26, 1912: 16; and elsewhere.

30 According to a widely-circulated Associated Press dispatch dated June 21, 1912.

31 “Bits of Baseball,” Washington (DC) Herald, June 16, 1912: 39.

32 “Bert Daniels of the Yanks Is a Marvel,” St. Louis Star, September 13, 1912: 9.

33 “Jennings Roasts Murphy of Cubs,” Bridgeport (Connecticut) Evening Farmer, December 21, 1912: 7. See also, “Hughie Likes Daniels,” Omaha Bee, February 16, 1913: 34.

34 W.J. Macbeth, published as “Training Yanks for Speed,” Evansville (Indiana) News-Journal, March 9, 1913: 20; “Chance Trails Others in Demand for Speed,” Memphis Commercial Appeal, March 9, 1913: 37; “Chance Trying to Drill More Speed into New York Yankees,” Seattle Times, Match 9, 1913: 28.

35 Same as above.

36 In Daniels’ defense, it should be noted that his 64.9 successful theft rate was the highest on the New York club.

37 Particularly cutting was another preseason piece which maintained that “speed never made a base runner and never will. … If ability to cover the ground with great rapidity were all that an athlete needs to steal bases, Bert Daniels of the Yankees would be one of the best in the business instead of one of the worst.” Mutt & Jeff, Atlanta Georgian, March 4, 1913: 15.

38 Per “Short Lengths,” Jackson (Michigan) Citizen Press, January 24, 1913: 12.

39 Although the American League’s New York entry had no official nickname, the club was usually called the Highlanders during its 1903-1912 tenure at Hilltop Park. The more headline-friendly Yankees or Yanks, however, had appeared in newsprint since 1904 and was almost universally adopted once the club moved to the Polo Grounds for the 1913 season. This profile utilizes the same club nickname differentiation.

40 “Yankees All Set,” Kalamazoo Gazette, April 9, 1913: 8.

41 Irving M. Howe, “Chance Has Job,” Columbus Dispatch, April 1, 1913: 16.

42 See again, “Yankees All Set,” Kalamazoo Gazette, April 9, 1913: 8

43 “Chance Handed Larry a Lemon Slab Artist,” (Jersey City) Jersey Journal, March 21, 1913: 19.

44 Bert Gallia, Joe Engel, and Long Tom Hughes were the Senator pitchers.

45 As reported in “Chance Busy Building Up the Yankees,” Elmira (New York) Star-Gazette, August 9, 1913: 9; “Yankees Paid Big Price for Maisel,” Paterson (New Jersey) Morning Call, August 9, 1913: 3; and elsewhere.

46 “Baseball Babble,” Jersey Journal, August 9, 1913: 7.

47 Per “Two More Birds Sold,” Baltimore Sun, July 15, 1914: 5; “Former Yanks Now Colonels,” Louisville Courier-Journal, July 15, 1914: 6. See also, “Sportograph,” Rockford (Illinois) Morning Star, August 9, 1914: 15, asserting that it was Daniels’ wife who objected to the Louisville move.

48 See “Barrow Puts Foot Down on Jumpers,” Newark Evening Star, May 21, 1914: 16. See also “Will Bring Zinn Home,” Baltimore Sun, July 17, 1914: 5; “Daniels May Join Knabes,” Washington Evening Star, July 17, 1914: 22.

49 Per C. Stark Mathews, “Daniels to Remain with Oriole Team,” Baltimore Sun, July 17, 1914: 8.

50 As reported in “Bert Daniels Bought by Reds,” New York Times, July 21, 1914: 7; “Daniels Bought by Redlegs,” Cincinnati Post, July 20, 1914: 2; and elsewhere.

51 See “Colonels to Get Bert,” Boston Herald, December 17, 1914: 8; “Bert Daniels Sold,” Cincinnati Enquirer, December 11, 1914: 6. The deal was a straight cash transaction but the amount that Louisville paid for Daniels was not publicly disclosed.

52 Daniels received a -1.8 Total Player Rating in the final edition of Total Baseball. Retosheet assigns Daniels a -.2.8 BFW.

53 Per “Daniels’ Leg Broken; Out for Two Months,” Louisville Courier-Journal, June 25, 1916: 42.

54 Trenton Evening Times, October 31, 1916: 13.

55 See “Bert Daniels Will Manage St. Joseph Ball Team,” Omaha World-Herald, April 6, 1918: 16; “Will Manage Saints,” St. Joseph (Missouri) News-Press, April 6, 1918: 8.

56 Per Western League stats published in the 1919 Spalding Official Base Ball Guide, 109. Baseball-Reference provides no data for Daniels in 1918.

57 Per “Dooin Signs Daniels,” Harrisburg Patriot, April 22, 1919: 11; “Bert Daniels to Play with Reading Team,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 21, 1919: 14.

58 As memorialized on Daniels’ TSN player contract card and reported in the Twin Falls (Idaho) News, June 25, 1921: 3.

59 As reported in “Daniels to Coach Jasper Ball Team,” Brooklyn Times, January 27, 1931: 74; “Bert Daniels Jasper Coach,” Yonkers (New York) Statesman, January 26, 1931: 14; and elsewhere.

60 According to the Jersey Journal, March 14, 1939: 15. At the time, Daniels was the chief engineer of Essex County.

61 The Daniels death certificate officially lists the cause of death as coronary thrombosis.

Full Name

Bernard Elmer Daniels

Born

October 31, 1882 at Danville, IL (USA)

Died

June 6, 1958 at Cedar Grove, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.