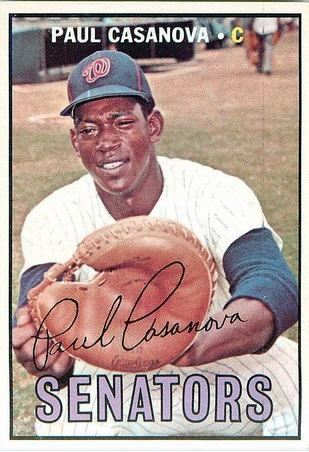

Paul Casanova

Paulino Casanova — known to English speakers simply as Paul — enjoyed his two best big-league seasons straight away. In 1966, the Cuban set a career high in homers with 13 and was named catcher on The Sporting News American League All-Star team. In 1967, he went to the midseason All-Star game for the AL. Casanova never hit as well after that, posting a lifetime average of .225 with the Washington Senators and Atlanta Braves. Yet his skills as a receiver — especially his outstanding arm — kept him in the majors through 1974.

Paulino Casanova — known to English speakers simply as Paul — enjoyed his two best big-league seasons straight away. In 1966, the Cuban set a career high in homers with 13 and was named catcher on The Sporting News American League All-Star team. In 1967, he went to the midseason All-Star game for the AL. Casanova never hit as well after that, posting a lifetime average of .225 with the Washington Senators and Atlanta Braves. Yet his skills as a receiver — especially his outstanding arm — kept him in the majors through 1974.

Casanova’s career had many intriguing dimensions. In his native Cuba, he apprenticed for two winters, from 1959-60 to the end of professional play there in 1960-61 — though he never got into a league game. Like another Caribbean catcher, Elrod Hendricks, two big-league organizations released him in the early ’60s — but he made it after paying a lot of dues at lower levels. Casanova played with the Indianapolis Clowns in 1961, as the barnstorming club kept the memory of the Negro Leagues alive. He stayed active and won notice in semi-pro ball. After making it to the majors, he also spent nine winters in Venezuela, from 1965-66 through 1974-75.

An elbow injury ended Casanova’s career during spring training 1975, but he came back to play in the Senior Professional Baseball Association at age 47 in 1989. He coached for several years in the minors, and later founded his own academy. In his seventies, he was still supporting the game at the grassroots level there, with the involvement of other former ballplayers from Cuba who came by to lend their expertise.

Paulino Casanova Ortiz was born on December 31, 1941 in Perico, a small city located in the Cuban province of Matanzas. Some baseball references currently show the date as December 21 and the place as Colón, but Casanova offered these corrections in 2012. Colón was the town where he was raised. His father, Alejandro Casanova, was a sugar cane laborer. His mother, María Herminia Ortiz, was a maid. Paulino was the fourth of seven children, all boys.

For insight on Casanova’s playing days — from childhood to his years as a professional — one rich source is his talk with author Brent Kelley for the book of interviews with Negro Leaguers, “I Will Never Forget.” He told Kelley, “Ever since I was a kid I wanted to play so bad. . .The reason why I became a catcher was because I was no good at all.” At the age of nine, he was so determined to play that he cut down a tree to make his own bat, fashioned a mask from wire, made his own glove too, and then formed his own team from the other kids who got left out.1

When he was 13, Paulino’s family moved to the capital city of Cuba, La Habana. There he played Little League and sandlot ball. He also got to play occasionally with a semi-pro team with many older men who had played black ball in the United States. Then, at the age of 17, he joined the Almendares Alacranes of the Cuban professional league. The chance came courtesy of Tony Taylor, a fellow Matanzas native who was then playing for Almendares and was in the early stage of his 19-year big-league career.2

With the Scorpions, Casanova sat and observed behind first-stringer Allen Jones, a career minor-leaguer; Enrique Izquierdo; and Jesús McFarlane.3 The youngster did not see any action even after Jones broke his right index finger and was lost for a few weeks.

The club’s part owner and general manager, Monchy de Arcos, was also head scout in Cuba for the Cleveland Indians.4 He gave Paulino a contract with the Indians, with a bonus of 200 Cuban pesos (then equal to US$200). In 1967, Casanova told Washington sportswriter Bob Addie, “I never forgot those 200 pesos. The first thing I did was give some money to my mama and then I went out and bought a lot of clothes. I always liked clothes. I didn’t know it then, but I was in for a lot of trouble before I ever got to the big leagues.”5

The young catcher went to spring training at Daytona Beach, Florida. The competition was heavy, but “I was willing to do anything,” Casanova told Addie. “They felt sorry for me and gave me a job as bullpen catcher” with Minot of the Northern League (Class C).6 He got into just 10 games, with a mere six at-bats. A 1969 feature from The Day of New London, Connecticut (where Casanova lived and worked for some time) said, “He was with the club a month when Minot acquired another catcher — a $30,000 bonus baby. Casanova was put on the reserve list. Released at the end of the season, he returned to Cuba.”7

Back with Almendares, Casanova continued to learn on the bench behind Izquierdo and McFarlane. Only Cubans played in the league’s final season. In the last game, on February 8, the pennant was on the line between Cienfuegos and Almendares, which entered with equal 34-31 records. But Pedro Ramos dominated for the Elephants, who won 8-2. With the game out of reach, Casanova, a “nervous 19-year-old. . .was about to get his first at-bat. But his dream never came true. Casanova was left standing in the on-deck circle when a teammate flied out to end the game. The next day he fled the country with six other players.” They went to the Mexican embassy and got visas for Mexico, and went from there to the United States.8 Casanova told Brent Kelley, “If I would’ve went back to Cuba I probably would’ve been Cuban and never got a chance to play here.”9

The Indians had invited Casanova back after his first season with Minot, but released him again in April 1961. Bob Addie told the story in 1967 of how “the breaks continued to go sour for the earnest young catcher.”10 However, Casanova corrected that version in 2012. Assigned to Newton-Conover in the Western Carolinas League, he took a cab from Charlotte — but he had no money in his pocket and could not explain to the irate cabbie that somebody with the club would pay. “I spent the night in jail since I had no place to sleep, and they were kind enough to allow me to sleep in one of the open cells until the next day when one of the police officers did me a favor and called Cleveland. A scout was sent to pay the cabbie, who had retained a glove and a pair of new shoes in collateral until his fee was paid,” Casanova recalled.

He then toured the country for three months with the Indianapolis Clowns, sleeping in the team bus most of the time. A big thrill came when he got a hit off Satchel Paige while going 5-for-5 in a morning/afternoon/night tripleheader. He also recalled hitting a homer off Joe Black, the former Brooklyn Dodger who was still active in semi-pro ball in New Jersey. He earned $300 a month. The Clowns paid half of his salary and San Antonio — then a Chicago Cubs farm club — paid the other half. Dick King, the general manager of San Antonio, recommended Casanova to the Cubs organization after seeing him play.11

That summer, the Clowns visited New London to play a team representing Electric Boat, the submarine manufacturer based in nearby Groton, Connecticut. This game had two big effects on Casanova. First, Washington Senators scout John Caruso (who was based in Holyoke, Massachusetts, where he owned a restaurant) saw him play. He said that he would be in touch about a contract. Second, the catcher met a New London woman named Minnie Johnson. “They corresponded during the summer and were married when Casanova returned to New London at the close of the season.” They had two children: Paulino Antonio and María Luisa.12

Casanova didn’t hear from John Caruso. He wondered what had happened; unbeknownst to him, the scout had been in a car accident and was hospitalized for six months. Meanwhile, “Casanova did a variety of odd jobs. In the winter, he shoveled snow with a street gang and, in the summer, he operated a steamroller for a construction company. . .He also worked part-time laying linoleum and did whatever [else] he could.”13 As he recalled in 2012, that included washing cars, which strengthened his arm.

Still just 20 years old, Casanova appeared twice for San Antonio in the 1962 season, with just one at-bat, before getting released once again in April. That summer he played for the Quaker Hill club in the Morgan League, a semi-pro circuit that operated in southeastern Connecticut from 1934 through 1985.14 That chance came thanks to Jorge Hernández, another Clowns veteran who had worked at the same trucking company with Casanova during the winter in New London.15

Casanova also played with Electric Boat’s team, which went up to Barre, Massachusetts for a tournament. John Caruso was there — for months, he had thought the young Cuban had gone back home. In the interim, a tryout with the New York Mets had come to nothing, but when Caruso saw Casanova’s arm on display, he signed him.16

In 1963 and 1964, Casanova played for Geneva, a Senators farm club in the New York-Pennsylvania League. He finally got some regular duty, playing 94 games and posting a .261-7-34 batting line in 1963. He started to emerge the following year, hitting .325-19-99 in 120 games and making the NYP All-Star team at catcher along with Jerry Moses.

Unfortunately, he did not have the opportunity to develop his game in winter ball in those years. Starting in 1962-63, former Commissioner Ford Frick had prevented Latino ballplayers from going anywhere other than their home country in the winters — which hit Cubans particularly hard, since the Castro regime had done away with their league. Casanova did, however, play in the Florida Instructional League.

Casanova spent his third year in A ball in 1965, hitting .287-8-76 in 142 games for Burlington of the Carolina League. That September, he got his first call to the majors; as Bob Addie in The Sporting News wrote, “The catching situation is acute with the Senators, which is the reason that Casanova is being given a trial.”17 He got into five games, and got his first hit — an RBI double off John O’Donoghue of Kansas City — on September 28 at D.C. Stadium.

In the winter of 1965-66, Casanova was able to play in Venezuela. He joined Tigres de Aragua, a first-year franchise whose batboy was a skinny young local named Dave Concepción — the future All-Star shortstop of the Cincinnati Reds.18 The club’s big star was Rico Carty. Carty was in South America that winter because the league in his homeland, the Dominican Republic, was still not operating amid political turmoil.19 More important, though, was the experience that Casanova gained by playing against major-leaguers such as Luis Aparicio.20

Casanova started off 1966 at Double-A, with York in the Eastern League. He played five games there but was then needed in Washington. As he told Brent Kelley, “The only reason I get my break because everybody get hurt and they had to play me.” John Orsino had a sore arm and so manager Gil Hodges put him at first base. Doug Camilli started most of the games behind the plate early on, but then he split a finger. In May, the Nats sent catcher Mike Brumley down and called up two receivers: Jim French and Casanova. In his second appearance, “Cassie” (or “Cazzie,” as his teammates also called him) hit his first big-league homer, breaking up a no-hitter by Fred Talbot of Kansas City in the eighth inning.

Soon after, Orsino went on the emergency disabled list — he had a cyst on a nerve in his throwing elbow that needed an operation. French’s knee bothered him, opening the door for Casanova to become the regular. In early June, Bob Addie wrote a description reminiscent of Charles Johnson, the big-league catcher of the 1990s and 2000s. “Big, good-natured Paul Casanova, with the arm of a rifle and the potentially-powerful bat, has been doing all the catching. . .He stands 6-4 and weighs 190 solid pounds.”21

After Doug Camilli went on to suffer a broken thumb, the Senators were so thin at catcher that they even activated coach Joe Pignatano, who had last played in the majors in 1963. Yet Casanova, despite being banged up all over like all big-league backstops, stayed in the lineup. Later that season, he got mention as an AL Rookie of the Year candidate. Longtime major-league catcher Rollie Hemsley, who lived in the D.C. area, had seen him in person at Senators home games and offered constructive criticism. Gil Hodges said, “He has done a remarkable job for his first year in the big leagues.”22

Casanova set career highs in games played (141), at-bats (551), and RBIs (53) in 1967. One particularly memorable game started on the evening of June 12. In Washington, the Senators and Chicago White Sox played a 22-inning marathon. Casanova caught the whole thing, receiving 268 pitches. As he recalled in 2012, “The reason the game went so long was because of my defense” — he wiped out a number of runners. He went 1-for-9, missing a chance to end it in the 20th when he hit into a third-to-home-to-first double play with the bases loaded — but his one hit was the game-winner at 2:44 A.M.23

In those days, the fans had still not regained the privilege of voting for the All-Star teams. The players, managers, and coaches cast the ballots, and Casanova came in second behind the AL’s clear-cut winner, Bill Freehan of Detroit. When the game was played, in Anaheim Stadium, Freehan stayed in throughout the entire 15-inning contest. Casanova was sad and disappointed that AL manager Hank Bauer did not see fit to use him at all, without even a word as to why.24

Casanova had much success that year with his arm against the White Sox, a running club. On August 28, the Senators beat the Sox, 2-1, thanks again to his defense. He picked Don Buford off third after Buford faked a dash to the plate. Then in the ninth, with Tommie Agee on third and Ken Berry on first, Duane Josephson struck out. Casanova bluffed Agee back to third after Berry lit out for second, then he threw to second baseman Tim Cullen, who trapped Agee off third to end the game. At various points that year, his snap throws picked runners off every base. Joe Garagiola, the catcher turned broadcaster, said to Casanova, “The Army could use you as a secret weapon. I never saw a gun like that.”25

The pitcher as the August 28 game ended was SABR member Dave Baldwin, who recalled the action in 2012. “That game in which Cazzie caught Agee off third occurred after he had acquired the reputation of having the best arm of all catchers in the American League. I remember thinking that we were lucky that Agee wasn’t paying attention to that reputation.

“Cazzie and I were teammates first at Burlington, North Carolina, in the Carolina League, in 1965. I was just learning to pitch at the age of 27, making the switch from throwing overhand to throwing sidearm and submarine. We were both learning a lot that season. He was very helpful to me, letting me know how the pitches were behaving (a pitcher can’t tell if the ball is sinking, sailing, or tailing). I remember he encouraged me to throw more screwballs, a pitch I should have used more throughout the remainder of my career.

“What I remember best about Cazzie is his rifle arm. The Washington coaches (Pignatano and [Rube] Walker) worked with him to improve his accuracy. Cazzie gained confidence and wasn’t afraid to try to catch runners off base, as Agee discovered.”

That winter, however, as a stipulation of Casanova’s new contract, Senators general manager George Selkirk forbade the catcher to play in Venezuela. Selkirk thought that it was wearing Casanova down late in the big-league season.26 By contrast, Paulino felt that winter ball benefited his summer hitting.27

The player may have known better than the GM. In 1968, he got off to a terrible start with the bat, and he was optioned to Triple-A Buffalo for a stretch during June and July. The slump and the demotion weighed on his mind and overall play.28 When he returned, things improved just a bit — he got over the Mendoza Line just once all year, on August 30, when his average stood at .201. He finished at .196, with 4 homers and 25 RBIs.

According to what he told Brent Kelley, Casanova was not skilled in calling a game when he first made it to the majors. When he focused on improving in that area, his hitting suffered — he modestly noted that he wasn’t the kind of catcher like Johnny Bench who could accomplish both things.29 Yet his arm remained powerful and accurate — during his big-league career, Casanova gunned down 40% of the runners who tried to steal against him (210 out of 524).

Casanova also told Kelley that he learned a lot from John Roseboro (a Senators teammate in 1970) and Earl Battey of Minnesota. He added that black catchers then were an elite few — akin to football quarterbacks, men of African descent found it hard to win the trust from management to call a game.30 He made another interesting point about Battey with Venezuelan columnist Broderick Zerpa, calling the Twins catcher the first whom he could remember to throw runners out from his knees. Casanova adopted the style himself, well before Benito Santiago gained wider notice for it.31

From 1969 through 1971, Casanova played under Ted Williams with the Senators. When Williams took over for Jim Lemon, Paulino said, “I’m looking forward to meeting him. Everybody says he’s a real nice guy. I’ll be glad to get all the help I can from a great hitter like him. He will bring up the morale of the team. The players will hustle for him.”32 Looking back in 2012, Casanova said of Williams, “A good friend of mine, a tremendous person. Wanted everyone to hit like him and nobody could hit like him.”

Casanova’s hitting did not pick up appreciably during his three last years in Washington: a .216 average overall, with 15 homers and 93 RBIs. He also remained a free swinger throughout his career, with an on-base percentage of just .252. Nonetheless, he still got the bulk of the catching duties over this period, ahead of the even weaker-hitting Jim French (.196 lifetime), John Roseboro (at the end of the line in 1970), and Dick Billings.

On December 2, 1971, the Texas Rangers — the move of the Senators franchise had been approved that September — traded Casanova to Atlanta for another catcher, Hal King. King was generally better known for his bat than his catching, yet he had hit just .207 in 1971. He was a lefty swinger, though, and the Rangers wanted him to pair with Billings and Ken Suarez (obtained the same day).33

From 1972 through 1974, Casanova was a backup catcher for the Braves. The first year, he was behind Earl Williams, a strong hitter who didn’t relish being behind the plate. In ’73, Johnny Oates came over from the Baltimore Orioles in the deal that sent Williams away, but he hurt his leg in July, and so Casanova was the starter during the second half of the year. In ’74, he was the third-stringer; Atlanta obtained Vic Correll near the end of spring training and gave Correll his first real chance to play in the majors. Overall, Casanova played in 173 games during those three seasons, batting .210 with 9 homers and 36 RBIs.

Casanova and Henry Aaron became quite friendly in Atlanta because they were both alumni of the Indianapolis Clowns.34 The biggest on-field highlight of his time in Atlanta was catching knuckleballer Phil Niekro’s no-hitter on August 5, 1973. Paul helped carry Niekro off the field “because he’s a beautiful guy.”35 Analyzing the game, he declared, “I’ve never seen his knuckler better and he threw 95% knucklers. I just tried to keep him cool and keep him throwing it. All I worried about was blocking the ball.”36

Padres manager Don Zimmer responded, “It’s pretty hard to hit a ball that Casanova can’t even catch.” When asked in 2012 about his approach to receiving the knuckleball, Paulino responded, “It is like catching butterflies with a catching glove.”

It’s also noteworthy that Ted Williams said, “Casanova is one of the better knuckleball hitters around.” That was in August 1969, after a game-winning pinch-hit homer off Wilbur Wood, who said, “He [Casanova] can hurt you with his power. He swings hard and when he makes contact, he can hit a long ball.” Paulino himself said, “I’ve been lucky against him” — actually, his record against butterfly artists was mixed. 37

Except for 1967-68, Casanova returned to Venezuela for winter ball through his big-league career. After his first two years with Aragua, he spent the rest of his South American career with Tiburones de La Guaira. Overall, during 450 games across nine seasons, he hit .268 with 20 homers and 200 RBIs. He was a member of three champion teams. In 1966-67, he reinforced the Caracas Leones in the playoffs; then he was with La Guaira as the Sharks won in 1968-69 and 1970-71.

In 2008, Casanova told Broderick Zerpa, “In Venezuela, they play a form of baseball that’s more fun than in the majors. The fans make you play and make you want to win each game. They’re not waiting for the playoffs, you have to win the games from early in the season.”38

Casanova was back with the Braves in spring training 1975, but Atlanta released him — which might not have been legal, for he had hurt his arm. A 1989 article showed him looking back. “Paul Casanova bends his right arm and with a long finger traces a scar running around his elbow. ‘After this, that was all,’ he says matter-of-factly. ‘It was over for me. I was only 33.’”39

In 1985, Casanova finally got to swing a bat in the uniform of the Almendares Blues. It came as he made his first appearance in the in the annual benefit for the Federation of Cuban Professional Baseball Players. He hit a double off Luis Tiant and said, “This is really exciting for me. I never got to play for (Almendares). I never had the feelings these other guys had. This is really my debut.” The story in the Fort Lauderdale Sun-Sentinel also emphasized Cuban camaraderie. “Unlike 24 years ago, Casanova was not playing to win. He was playing to see old friends, sign autographs for Latin American fans and share old memories. ‘It really doesn`t matter what teams we’re playing for,’ Casanova said. ‘It`s always exciting when we get together again.’”40

When the Senior Professional Baseball Association began play in the fall of 1989, Casanova joined the Gold Coast Suns, managed by Earl Weaver. He said, “This is like coming back to life. When you have to leave the game and you get a chance to come back to it, that’s when you appreciate what the game is.”41

In 1992, Casanova became part of the Chicago White Sox organization. He told Brent Kelley that at first he was going to be bullpen coach with the big club, but because of vision problems, he wound up instead with their Class A farm team in Hickory, North Carolina as a first base coach and catching instructor. One of the young players he came to with Hickory there was Magglio Ordóñez, then still a teenager. “I worked there for two years, going on three,” Casanova recalled, “But when the strike came they let everybody go.”42

In March 2010, SABR member Nick Diunte devoted one of his regular columns to “Paul’s Backyard,” as Casanova’s academy affectionately became known for its location. He praised Paulino and his fellow Cuban, former big-league shortstop Jacinto “Jackie” Hernández, for their vigor, love for the game, keen eyes, and relaxing, encouraging nature.43 Plenty of people shared Diunte’s opinion.

Along with all its training equipment, the academy also served as “a virtual museum with a focus on the Cuban legends who represent Casanova and Hernandez’s home country.”44 Casanova was an ambassador of sorts, keeping in touch with many of the Cuban vets living in South Florida. Younger big-leaguers had ties to the academy too, such as J.D. Martínez. “Flaco” trained under Casanova and Hernández and rewarded them with his first homer in the majors on August 3, 2011.45

Paul Casanova was a most amiable personality — photos of him almost without exception showed a pleasant smile on his face. As Broderick Zerpa put it, “To talk with Paulino Casanova is an activity that, aside from being a lot of fun because of his great sense of humor, is really educational for those who want to learn more about baseball every day. Without doubt, to talk with this baseball globetrotter is to get to know in depth the game at the end of the ’60s and beginning of the ’70s in the Caribbean and the Big Show.”46

Casanova appeared at Major League Baseball’s FanFest as part of the entertainment surrounding the 2017 All-Star Game, which was held in Miami. He was in a wheelchair, because for some time he’d had severe back problems and other health issues that required regular medical attention and some hospitalizations.47 Nonetheless, he was in typical good humor as he talked about how salaries had spiraled since he broke into the majors. “We only played because we loved the sport,” he said.48

During 2017, Casanova had been suffering from respiratory problems, and severe cardiorespiratory complications ensued after his public appearance in Miami. On August 12, he died at the age of 75, surrounded by family members. His remains were to be cremated.

Nick Diunte wrote a column for the website La Vida Baseball full of warm memories — his own and others’ — about Casanova. Diunte observed, “Paul was the glue that held together a generation of baseball players,” and added, “Look at the game of today, and Casanova’s fingerprints are all over it.”49

Luis Tiant, who heard the news from fellow Cuban Tony Oliva, was saddened by the loss of his longtime friend, with whom he had played in Cuba and Venezuela. Jackie Hernández underscored Tiant’s emphasis on how caring Casanova was and how much he helped others. “To the end a good and respected person,” said Hernández. “Casanova was very proud that his baseball academy helped so many youngsters learn and enjoy the game and advance in their career.”

An earlier version of this biography appeared in “Cuban Baseball Legends: Baseball’s Alternative Universe” (SABR, 2016), edited by Peter C. Bjarkman and Bill Nowlin.

Acknowledgments

Grateful acknowledgment to Paulino Casanova for his ongoing help with the SABR BioProject’s effort to honor Cuban ballplayers. He provided handwritten comments on his own story to José Ramírez on a draft copy (reply received July 2, 2012). Thanks also to Dave Baldwin for his memories (via e-mail, June 7, 2012) and to Nick Diunte.

Continued thanks to Jackie Hernández and Luis Tiant for their ongoing input, especially following the loss of their dear friend (conversations with José Ramírez, August 13, 2017).

Sources

Books

Jorge S. Figueredo, Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball, 1878-1961. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc. 2003.

Internet resources

www.baseball-reference.com

www.retrosheet.org

www.purapelota.com (Venezuelan statistics)

www.checkoutmycards.com

Notes

1 Brent Kelley, “I Will Never Forget”: Interviews with 39 Former Negro League Players. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2003, 16. The Casanova interview took place in late 2000 or early 2001, since he noted that his friend Tommie Agee had just died.

2 Kelley, “I Will Never Forget”, 16-17.

3 McFarlane’s full given name was Orlando de Jesús, and he was known as both Orlando and Jesús in his playing days.

4 For more on the life and career of Julio “Monchy” de Arcos, see his obituary in The Sporting News, April 16, 1966, 56. He died in a car accident in Florida at the age of 43.

5 Bob Addie, “Luck, Pluck Made Casanova Darling of Senators’ Hearts,” The Sporting News, April 8, 1967, 20.

6 Addie, “Luck, Pluck Made Casanova Darling of Senators’ Hearts.” Kelley, “I Will Never Forget”, 16.

7 John DeGange, “The Paul Casanova Story,” The Day (New London, Connecticut), February 20, 1969, 41.

8 Randall Mell, “Like Old Times,” Fort Lauderdale Sun-Sentinel, December 16, 1985.

9 Kelley, “I Will Never Forget”, 16.

10 Addie, “Luck, Pluck Made Casanova Darling of Senators’ Hearts”

11 Kelley, “I Will Never Forget”, 13-15.

12 DeGange, “The Paul Casanova Story”

13 Addie, “Luck, Pluck Made Casanova Darling of Senators’ Hearts”

14 Jack Cruise, “Morgan League disbands,” The Day, March 26, 1986, D1.

15 DeGange, “The Paul Casanova Story”

16 DeGange, “The Paul Casanova Story.” Kelley, “I Will Never Forget”, 14.

17 Bob Addie, “Senators Bring Up Five from Hawaii Farm club,” The Sporting News, September 18, 1965, 17.

18 Broderick Zerpa, “Paulino Casanova: ‘En Venezuela la pelota es más divertida,’” Línea de Primera, November 26, 2008 (http://lineadeprimera.wordpress.com/2008/11/26/paulino-casanova-%E2%80%9Cen-venezuela-la-pelota-es-mas-divertida%E2%80%9D/)

19 That winter, there was a three-team circuit formed by the Federation of Dominican Players. The teams represented colors rather than cities: the Blues, Yellows, and Reds.

20 Kelley, “I Will Never Forget”, 17. Casanova re-emphasized this in his last public appearance in July 2017.

21 Bob Addie, “Selkirk Won’t Ask Settlement from Birds for Ailing Orsino,” The Sporting News, June 4, 1966, 21.

22 Bob Addie, “Nat Casanova Makes Goo-Goo Eyes at Rookie of Year Prize,” The Sporting News, September 3, 1966, 20.

23 Bob Addie, “Nats Go Home with Milkman; 6-Hour Frolic,” The Sporting News, June 24, 1967, 11.

24 Merrell Whittlesey, “Casanova Loses Cool over Nat Cold Shoulder,” The Sporting News, July 13, 1968, 24.

25 Bob Addie, “Casanova’s Rifle Wing Amazes Garagiola,” The Sporting News, September 16, 1967, 27.

26 Bob Addie, “Casanova First of Nats in Fold; Mitt Star Pockets $5,000 Hike,” The Sporting News, November 18, 1967, 32.

27 DeGange, “The Paul Casanova Story”

28 Whittlesey, “Casanova Loses Cool over Nat Could Shoulder”

29 Kelley, “I Will Never Forget”, 15.

30 Kelley, “I Will Never Forget”, 17.

31 Zerpa, “Paulino Casanova: ‘En Venezuela la pelota es más divertida’”

32 DeGange, “The Paul Casanova Story”

33 Merle Heryford, “Rangers Size Up Foster as Home-Run Threat,” The Sporting News, December 18, 1971, 47.

34 Kelley, “I Will Never Forget”, 19.

35 Wayne Minshew, “A First for Atlanta — Niekro’s No-Hit Gem,” The Sporting News, August 18, 1973, 22.

36 “Niekro: Brave No-Hit World,” wire service reports, August 6, 1973.

37 Bob Wolf, “Knuckleball to Casanova Was Just a Sitting Duck,” Milwaukee Journal, August 7, 1969, 16. Though Casanova was 6 for 14 (.375) against Wood, he was 4 for 17 (.235) against Eddie Fisher and 1 for 10 (.100) against Hoyt Wilhelm.

38 Zerpa, “Paulino Casanova: ‘En Venezuela la pelota es más divertida’”

39 “Playing Extra Innings,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, October 31, 1989, E1.

40 Mell, “Like Old Times”

41 “Senior baseball league offers opportunity to revive love affair,” wire service reports, November 2, 1989.

42 Kelley, “I Will Never Forget”, 18.

43 Nick Diunte, “Baseball lives in Paul’s backyard,” Examiner.com, March 28, 2010 (http://www.examiner.com/article/baseball-lives-paul-s-backyard)

44 Ibid.

45 Nick Diunte, “J.D. Martinez’s first home run excites cheers in Hialeah,” Examiner.com, August 3, 2011 (http://www.examiner.com/article/j-d-martinez-s-first-home-run-excites-cheers-hialeah)

46 Zerpa, “Paulino Casanova: ‘En Venezuela la pelota es más divertida’”

47 Brooks Robinson was severely injured in January 2012 after falling from a stage during a charity event at the Seminole Hard Rock Hotel and Casino in Hollywood, Florida. Casanova had also fallen from the same stage earlier that night. However, according to Nick Diunte, who was at the event, Casanova — unlike Robinson — did not suffer lasting complications from his fall. E-mail from Nick Diunte to Rory Costello, August 14, 2017.

48 Catalina Ruiz Parra, “Homenaje a las leyendas latinas del béisbol,” El Nuevo Herald (Miami, Florida), July 8, 2017.

49 Nick Diunte, “Paul Casanova: Everyone’s ‘Hermano,” La Vida Baseball, August 13, 2017 (https://www.lavidabaseball.com/paul-casanova-everyones-brother/).

Full Name

Paulino Casanova Ortiz

Born

December 31, 1941 at Perico, Matanzas (Cuba)

Died

August 12, 2017 at Miami, FL (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.