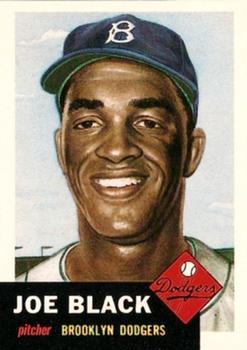

Joe Black

Joe Black helped lead the Brooklyn Dodgers to the 1952 pennant, going 15-4 with 15 saves, and a 2.15 ERA. He won the NL’s Rookie of the Year Award and became the first African American pitcher to win a World Series game. “Let’s put it this way,” Dodgers manager Chuck Dressen told reporters, “Where would we be without him?”1 Teammate Carl Erskine said, “He put us in the World Series. He was the main cause to get us there.”2

Joe Black helped lead the Brooklyn Dodgers to the 1952 pennant, going 15-4 with 15 saves, and a 2.15 ERA. He won the NL’s Rookie of the Year Award and became the first African American pitcher to win a World Series game. “Let’s put it this way,” Dodgers manager Chuck Dressen told reporters, “Where would we be without him?”1 Teammate Carl Erskine said, “He put us in the World Series. He was the main cause to get us there.”2

During the middle of the 20th century, Black, along with Joe Page, Jim Konstanty, and Hoyt Wilhelm, helped define the importance of relief pitching as a specialty. Managers and fans began to recognize relievers’ value to teams rather than view them as failed starting pitchers.

Black was born on February 8, 1924 in Plainfield, New Jersey, an industrial and residential city of 30,000 people, 13 miles from Newark. He grew up in a racially mixed working class neighborhood with white friends in school and in the community, including in his athletic activities. He was the third of six children born to Joseph Black and Martha Watkins Black. His father, a skilled mechanic, had to resort to menial part-time jobs until he found a job in 1937 with the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration. His mother took in laundry and worked as a cook and housekeeper for white families. Starting at nine years old, Joe took odd jobs to help the family. He and his siblings wore hand-me-down clothes, but were never hungry. His parents were religious, strict and demanded respectful behavior. Joe’s mother never got past third grade and could barely read or write, but insisted that her children do well in school. “Ain’t nobody better than you,” she asserted. Black and other low-income students “made a determination to prove that we were not dumb despite the fact that we were poor.”3

Some Plainfield police officers provided Black and his friends with equipment and uniforms and taught them how to play team baseball.4 By the time he reached Plainfield High School (PHS), Black was an outstanding athlete and excellent student. He played on the football and basketball teams and played first base, third base, left field, and catcher for the baseball team, but did not pitch.5 He was named PHS’s outstanding athlete for the 1941-42 school year.6

Black was fortunate that Plainfield had many amateur and semi-pro sports leagues that supplemented his high school athletic activities on weekends and during summers. Some of these team rosters included former and current minor league, college, and Negro League players. He pitched and played catcher, infield, and outfield — often playing multiple positions in one game.

As he was nearing his high school graduation in 1942, his dream of playing in the majors was shattered.

“I was batting .400 when I was a senior in high school. The scouts were talking to other people, but they didn’t speak to me. I said, ‘Hey, I am the captain of the team. I out-hit them all — why don’t you sign me?’ A scout said, ‘Because you are colored, and they don’t play baseball in the big leagues.’” As Black recalled, “I got mad and hateful. I had a scrapbook of ballplayers, and I tore up all of their pictures — they were all white. The one picture that I didn’t tear was Hank Greenberg, my idol. He was big and hit home runs, and that’s what I wanted to do. My mother said, ‘Son, you can’t be mad.’ I said, ‘But mama, white people won’t let me play!’”7

During the summer after his 1942 high school graduation, Black kept up his frenetic pace. He played on several teams in different local leagues, including the Plainfield Black Yankees, for whom he pitched and played in the infield.8 Simultaneously, he worked nights in a factory.9 In a game on May 31, Black played second base and hit two home runs.10 Two weeks later, Black pitched, played second base, had two hits, and scored three runs.11 A week later, the Plainfield Courier-News reported that “Big Joe Black, pitcher, infield, outfielder, and catcher, depending on the needs of his team, took a turn on the mound Sunday afternoon and entered baseball’s mythical hall of fame by hanging up a no-hit, no-run game at the expense of the Bound Brook Indians, 12-0, at Cedarbrook Park.”12 That summer he also pitched for the Abbond-Royal team, a business-sponsored club in the Plainfield area Twilight League.

Black received a partial football scholarship at Morgan State College [now University], a historically black institution in Baltimore, beginning in September 1942. Growing up in Plainfield, Black had felt the stings of prejudice and discrimination, but moving to Baltimore, a legally segregated city, was a different experience.

As he recalled, “You would go into a store to try on a pair of shoes, and you couldn’t try them on. You couldn’t try a coat on. You bought stuff, but you couldn’t bring it back—whether it fits or not.”13

In college, he learned about Black history; that gave him a new-found pride in his race.14 He joined Omega Psi Phi fraternity and made lasting friendships.

Although Morgan State did not have a baseball team, Black was still a three-sport athlete in college — playing end and defensive back for the football team, center on the basketball team, and competing in the high jump and hurdles on the track team.

In the summer of 1943, after his freshman year, Black and his college friend Cal Irvin (brother of future New York Giants star Monte Irvin) went to a Negro League game between the Baltimore Elite Giants and the Newark Eagles at Bugle Field. Vernon Green, the Elite Giants’ business manager, overheard Black boasting that he was as good or better than some of the players on the field. Green arranged for Black to try out for the team. He played several games at shortstop, hit poorly, and asked the manager to give him a chance to pitch.15 The official Negro League record book lists Black as having pitched in two games for the Elite Giants that season.16

Black joined the Army Medical Corps on August 17, 1943.17 He served for 2 ½ years in the Army during World War 2, until March 1946.18 “Sixteen months after I was drafted before I touched a rifle. I pitched a lot,” he told Roger Kahn.19

At the Veterans Administration Hospital at Stewart Field air force base on Long Island, he was assigned to an all-black unit in the Physiotherapy Department, trained to work with shell-shocked soldiers suffering from various mental disorders.20 While stationed in Long Island during football season, he played with the Carters football team in Plainfield’s semi-pro league on weekends.21 During baseball season, he played for the Elite Giants during weekend passes and furloughs, pitching nine games in 1944 (3-3) and one game in 1945 (0-1). In 1945, after a seven month stint at Camp Barkeley in Texas, his battalion was moved to Missouri’s Camp Crowder.22 The Stewart Field Panthers were racially integrated but Camp Crowder was segregated. However, the military brass made an exception for Black, allowing him to pitch for the otherwise all-white baseball team.23 The coach, Tommy Bridges, an All-Star pitcher with the Detroit Tigers, helped Black improve this pitching.24 When the team went on road trips to play other military teams or college teams, Black had to stay in the bus while his white teammates ate at Southern segregated restaurants. When Camp Crowder’s basketball season came around, however, Black was back on an all-black team.25

Black was 21 years old and still in the Army, when, in October 1945, Branch Rickey signed Jackie Robinson. ”I started dreaming,” Black recalled. “And that’s what happened to most of the guys in the Negro Leagues. You forgot your age. You said, ‘If Jackie makes it, I can make it.”’26

A month after his Army discharge in March 1946, Black was back with the Elite Giants for whom he played that season. He returned to Morgan State for his sophomore year (playing football and basketball) and returned to the Elite Giants during the summer of 1947. That fall, a few months into his junior year, Black left Morgan State to accept an $800 month offer to pitch in the Venezuela winter league for the Magallanes team.27 He started 10 games, finished six, relieved in seven more, pitched 94 innings, won four games, and lost seven.28 Black spent several winters playing in winter leagues in Mexico, Venezuela, and Cuba.

In March 1948, he rejoined the Elite Giants and played with them each spring and summer until 1950, winning 45 games and losing 37. In 1946 and 1947 he led the Negro National League in games pitched (20 and 26, respectively), but his best years were 1948 through 1950, when he was 10-5, 11-7 and 8-3, as a starting pitcher. He pitched in the 1947, 1948, and 1950 All-Star East-West games at the Polo Grounds, Yankee Stadium, and Comiskey Park, respectively, and helped the Elite Giants win the 1949 Negro League National Championship.29

During the 1949-50 off-season, he returned to Morgan State to take courses toward his degree in psychology and physical education. After graduating in 1950, at 26, Black pitched for the Elite Giants during the summer, then joined a barnstorming team of Black players led by Luke Easter. In the fall, Black joined the Cienfuegos Elefantes in the integrated Cuban winter leagues.

While in Cuba in 1950, Black met Fidel Castro, then a young lawyer and budding politician. Castro often attended winter league games. In addition, Black played a one-on-one basketball game with the future “jefe.” Castro corresponded with Black when Black was with the Dodgers in 1952.30

While in Cuba in 1950, Black met Fidel Castro, then a young lawyer and budding politician. Castro often attended winter league games. In addition, Black played a one-on-one basketball game with the future “jefe.” Castro corresponded with Black when Black was with the Dodgers in 1952.30

In 1951, the Dodgers purchased his and Jim Gilliam’s contracts from the Elite Giants for $11,000.31

The Dodgers sent Black to their Triple-A teams in Montreal and St. Paul, where he posted a combined 11-12 record with a 3.28 ERA.32

During the winter he returned to Cuba to play for the Cienfuegos team. Ray Noble (a Cuban catcher for the New York Giants), and Cienfuegos manager Billy Herman helped Black improve his control and set batters up. “It was there,” Black recalled, “that I truly learned to combine the mental and physical aspects of pitching.”33

In Cuba, Black pitched 163 innings in 27 games, leading the league in ERA (2.42) and games won (15), while losing six games.34

Black’s time in Cuba opened his eyes “to recognize that all societies don’t use skin pigmentation as an evaluation tool.”35 Even in Montreal and St. Paul — far from the American South — Black confronted racism, including the N-word and other slurs, much more from opposing teams’ players than from the fans.36

Black pitched 170 innings in the minors and another 163 innings in Cuba, so his arm was sore when he showed up at the Dodgers’ Vero Beach spring training camp in 1952.37 He didn’t tell anyone. He had neither a contract nor a place on the roster.

The team’s spring training facility, Dodgertown, was integrated. Black and white players slept, ate, and practiced together in the compound. It had its own swimming pool, basketball court, pool tables, and occasional movie nights. But the world immediately outside Dodgertown was segregated. Blacks couldn’t eat in the restaurants or get a haircut and were banned from Vero Beach’s beaches, movie theaters, and golf courses. Laundries wouldn’t take their clothing. When the Dodgers traveled to play exhibition games, black and white players had to stay in separate hotels.38

The Dodgers assigned Black to room with Robinson. When Robinson walked into the room they were sharing in Vero Beach, he asked Black, “Can you fight?” “Yeah,” Black responded. “But we’re not going to fight,” Robinson said. He explained, “We can’t allow those crazy sons of bitches to bother us. We have the ability to play, and we’re going to show them that we’re in baseball to stay.”39 Robinson took the time to “impress upon me the psychological changes that must be endured by the black ballplayers,” Black recalled.40 Robinson had endured racial slurs from fans and opposing players, even years after he’d established himself as a star ballplayer. “I couldn’t have done it,” Black said.41

Rooming with Robinson helped give Black the perspective he needed to channel his anger on the mound. Several white Dodgers extended their hand in friendship to Black, including Preacher Roe, who was the first player to greet him when he arrived at the Vero Beach clubhouse. Roe was an outstanding pitcher who grew up in rural Arkansas, and who, like Black, was one of the few players to have graduated from college.42 Other players helped him adjust to pitching in the majors. Catcher Roy Campanella taught Black not to tax himself too much while warming up before games. He observed that he was “throwing your best pitches before the game.”43

The Dodger rookie would become the 25th person of color to play in the major leagues in the 20th century. He was only the fifth Black pitcher. He was the fifth Black player to wear Dodger Blue.

Manager Chuck Dressen first put Black into a game on May 1 when he started the seventh inning against the Cubs at Wrigley Field. He struck out slugger Hank Sauer (that year’s NL MVP), struck out third baseman Randy Jackson, and got catcher Toby Atwell (who was leading the NL in batting) to ground out to second base.44 The game put the Dodgers in first place, ahead of the Giants, where they would remain for the rest of the season.

After his first seven appearances (14 innings), Black’s ERA stood at 0.00. At the All-Star break, Black was 3-0 with five saves in 38 2/3 innings, with a 1.63 ERA. Dressen relied on him more during the second half of the season. Black lifted up the Dodgers to help compensate for the loss of Don Newcombe (who was in the army) and for the injuries to the other pitching mainstays, including Preacher Roe, Carl Erskine, and Ralph Branca. Dressen used Black as a utility reliever. In his 54 relief appearances, he pitched less than two innings 22 times, two innings 17 times, three innings four times, four innings four times, five innings three times, six innings twice, seven innings once, and eight innings once. Eight of his 11 stints pitching four innings or more occurred down the stretch in August and September.45

By the end of the season, he had appeared in 56 games with a 15-4 record and 15 saves. In 142 innings, he struck out 85 batters, walked only 41, and gave up just nine home runs. Black’s 2.15 ERA was the NL’s lowest, but he was eight innings short of the threshold for the title. The winner was another rookie reliever, the Giants’ Hoyt Wilhelm, with a 2.43 ERA in 159 innings.

Black, who stood 6’2” and 220 pounds, with broad shoulders, long arms, and big hands, had only two pitches — a powerful fastball and a “nickel curve,” which broke like a slider. He made up for his limited repertoire by having pinpoint control.46

Toward the end of the season, Black received a letter that included a death threat from someone claiming to be a Giants fan. Black had to endure a police escort to and from the ballpark.47

Throughout the season, Black faced racist catcalls from fans and opposing players. When that happened, Robinson would typically walk to the mound to calm Black down. “Forget it,” he said. “Just pitch.”48 One night after a game with the Cardinals, Stan Musial apologized for his teammates’ racist remarks. “I’m sorry that happened,” Musial said, “but don’t let things like that bother you. You’re a good pitcher.”49 At that time, the Cardinals did not have a single person of color in their entire organization.

Black could intimidate opposing hitters by knocking them down with his fastball. “We’re professionals,” he explained. “If I send a guy into the dirt, it isn’t personal.” But at times he used the knock-down pitch as a weapon against racism. In one game, players on the all-white Cincinnati Reds (they did not integrate until 1954) began singing “Old Black Joe” from the opposing team’s dugout, trying to rattle Black on the mound. “I was seething,” Black recalled. He quickly knocked down several Reds hitters. After that, Black recalled, “The singing came to a halt.”50

Dressen started Black in his two final games of the season, thinking that he might have to use him as a starter in the World Series.

The World Series was between two New York City teams. They were scheduled to play seven games in seven days, with no travel days in between. That shaped Dressen’s decision to start Black in the first game, anticipating that he would pitch the fourth game and, if necessary, the seventh game.

Wrote AP sportswriter Gayle Talbot, “Never before in big league history has a champion of either circuit been forced to undertake such as desperate gamble.”51 New York Times writer John Debringer wrote that Black “found himself cast in as difficult a role as ever was assigned to a rookie.”52

In the opening game, Black threw a six-hitter to beat Allie Reynolds 4-2, making him the first African American pitcher to win a World Series game. 53 Three days later, Black faced Reynolds again in the fourth game at Yankee Stadium. Black gave up only three hits and one run in seven innings. But Reynolds pitched a shutout and defeated the Dodgers 2-0. (Dodgers reliever John Rutherford gave up another run in the eighth inning).54 Strapped for pitching, Dressen called on Black to start the seventh game at Ebbets Field. “Brooklyn’s Hopes for Series Honors Ride on Trusty Arm of Joe Black Today,” read the New York Times headline that morning.55 Black pitched well for three innings, giving up no hits and no runs, but then, in his third start in seven days, he ran out of gas. In both the fourth and fifth innings he surrendered two hits and one run, including a homer by Gene Woodling. In the sixth inning, Black gave up a home run to Mickey Mantle and a single to Johnny Mize. Dressen brought in Roe to relieve Black. Four Yankee pitchers held the Dodgers to two runs for a 4-2 victory and the World Series championship.

Although Black was aggressive on the mound, he had an easy-going personality. He got along well with reporters. The press liked Black because he was smart, articulate, and straightforward with them. New York Times sports columnist Arthur Daley wrote that Black is “far more intelligent than the average ball player, better educated (he’s a graduate of Morgan State College) and has a sharper sense of humor.” Black, he wrote, was “just bursting with class.”56

For the most part, reporters treated him well in their stories. At the end of the pennant race, and after the Sporting News had named him Rookie of the Year, Black sent a bottle of scotch to the scribes who traveled with the Dodgers during the season as a “small token of gratitude for having written so many nice things about me this season.”57

Toward the end of the season, sportswriters debated whether Black or Wilhelm would win the NL’s Rookie of the Year award, selected by the Baseball Writers Association of America. Wilhelm had a better W-L record (15-3 vs. 15-4), pitched in more games (71 vs. 56), and hurled more innings (159 vs. 141). Black had a better ERA (2.15 to 2.43) and his team won the pennant. Wilhelm’s Giants finished second. Nineteen writers voted for Black; only three voted for Wilhelm.58

Most baseball experts expected the NL MVP award to go either to Black or Robin Roberts. The righty Roberts was 28-7 with 30 complete games with the fourth-place Philadelphia Phillies. 59

But when the BWAA made the announcement on November 21, Hank Sauer, the slugging outfielder for the fifth-place Chicago Cubs, was declared the winner. Sauer tied for the NL lead in homers (37), led the league in RBIs (121), and batted .270.

The selection of Sauer was controversial among sportswriters and fans.60 United Press sportswriter Oscar Fraley observed that “anybody who knows the difference between a bunt and a punt must be completely flabbergasted” by Sauer’s selection.61

Twenty-four baseball writers, three from each National League city, cast ballots.62 Sauer received 226 votes, Roberts 211, and Black 206, followed by Wilhelm (133 votes) and Musial (127 votes). Sauer and Black each got eight first-place votes, followed by Roberts’ seven first-place tallies. (The Dodgers’ Duke Snider earned the one other first-place vote).63

Some writers may have believed that an everyday player, not a pitcher, should get the MVP award.64 Between 1911 (when the award was first bestowed) and 1951, only 12 pitchers, and one reliever (the Phillies’ Jim Konstanty in 1950), had won that prize. Sauer may have prevailed because writers divided their votes between three pitchers — Black, Roberts, and Wilhelm — which allowed Sauer to win the award.65

According to United Press’ Fraley, three of the 24 writers left Black’s name off their ballots entirely and one gave Black a tenth-place vote. Jackie Robinson approached one of those writers and accused him of racism.66

This controversy over whether pitchers should get the MVP over everyday position players led eventually to creation of the Cy Young award for best pitchers in 1956.

Despite starting three World Series games and winning the Rookie of the Year award, Black accepted a contract for only $12,500 for the next season.67

Black players had fewer opportunities to earn extra money from endorsements than their white counterparts. But after his rookie season, Black — a genuine star and photogenic — made money doing ads for Lucky Strike cigarettes (even though he didn’t smoke) and writing a column, sponsored by Lucky Strikes, which ran in black newspapers. In one June 1953 column, Black described how teammates Pee Wee Reese and Robinson approach base stealing, concluding, “Yessir, base stealing adds a lot of enjoyment to a ballgame. Just like Luckies will add a lot of enjoyment to your smoking hours once you’ve made them your steady smoke.”68

Near the end of the baseball season, Dressen told Black that he might need him to become a starting pitcher and that he should add a new pitch to his repertoire. While pitching for Roy Campanella’s all-Black post-season barnstorming team, Black experimented trying to throw a knuckleball, without success. When Black got to Vero Beach for spring training, he tried to learn to pitch a forkball, a change-up, and a sinker, but he couldn’t grip the ball properly because of a deformity he had on his index finger. The Dodger coaches worked with Black to experiment on his stride on the mound, at times urging him to lengthen it and at other times to shorten it. Nothing worked, so Dressen told Black to go back to his former pitching style. But by then Black had forgotten what he’d done to achieve so much success in his rookie year. He couldn’t get his old form back, and each time he took the mound — during spring training and after the season started — he had lost his form and, with it, his confidence.69

In his second season, Black was no longer the domineering pitcher he had been in 1952. He could still throw hard, but his control, timing, and pitching mechanics suffered. His teammates and even players on opposing teams offered advice, but it didn’t help. By July, Dressen no longer trusted Black as the closer. Black pitched in fewer games and clutch situations. Black recalled that “I was not a pitcher. I was a thrower, without control or confidence.”70 The Dodgers won the pennant, but Black’s contribution was nothing like his previous year’s record. He pitched in 34 games and only 71 innings. His W-L record was 6-3, but his ERA skyrocketed to 5.33. He had only five saves. He pitched only one inning during the Yankees-Dodgers six game World Series.

In 1954, the Dodgers’ new manager, Walter Alston, used Black sparingly. By May 26 he had pitched in five games and given up 11 hits, including three homers in seven innings, walked five batters, and struck out three, with a 11.57 ERA.71

On May 30 the Dodgers demoted him to their Montreal AAA team. Soon after arriving in Montreal, the team doctor discovered that Black had torn muscles in his right shoulder. This helped account for the loss of speed on his fastball. For the rest of the season, a doctor gave him weekly cortisone shots to ease the pain. His performance improved. He started 24 games and relieved in seven more. In 185 innings, he struck out 94 batters and walked 61, but allowed 181 hits. He won 12 games, lost 10 games, and finished with a 3.60 ERA.

Black spent the fall barnstorming again with Campanella’s all-stars, showing signs of recovering his rookie year brilliance.72 He pitched 15 innings with a 2.93 ERA, but it didn’t satisfy the Dodger brass. On June 9, they traded him to the Cincinnati Reds for outfielder Bob Borkowski. That year the Dodgers would win their first World Series, but Black was no longer on the team.

The Reds used him in as both a starter (11 games) and reliever (21 games). He pitched 102 innings, went 5-2, with a 4.22 ERA.

In 1956, manager Birdie Tebbetts used Black exclusively in relief. He accumulated a 3-2 record and 4.52 ERA in 32 outings, but his performance was uneven. He won his last major league game on June 24, going five and two-thirds innings without giving up a hit to beat the Dodgers in relief.

In January 1957, the Redlegs sold Black to the Seattle Rainiers in the Pacific Coast League. During the Rainiers’ spring training in San Bernardino, Black’s arm began hurting. A doctor at the local VA hospital did X-rays. They revealed bone chips in his right elbow and a small crack developing in his humerus, the bone from the shoulder to the elbow. Afraid of being let go, he didn’t tell anyone. Manager Lefty O’Doul used Black as both a starter and reliever. In 23 2/3 innings he gave up 34 hits and 17 runs.73

On May 25, after going 1-1, with a 4.94 ERA, Black was sold to the Tulsa Oilers, a Phillies franchise in the AA Texas League.74 He made his first start on June 4 against Oklahoma City. Black pitched nine innings and left with the score tied 5 to 5. At the end of June, he was put on the disabled list with a sore arm. After a few more so-so outings, Tulsa released him on July 16. By then, he could barely lift his arm.

At the end of July, after serving as a part-time batting practice pitcher with the Dodgers,75 Black contacted Washington Senators manager Cookie Lavagetto, a former Dodger infielder, to ask for a chance. The Senators signed him as a free agent on August 1, making him the team’s first American-born black player.76 (The team had three black Cubans and one black Panamanian before hiring Black).77

Black had lost the velocity on his fastball, and lost his confidence, and players teed off on him. He pitched seven games and 12 2/3 innings for the Senators, giving up 22 hits, losing one game, and ending the season with a 7.11 ERA. His last major league outing was on September 11, 1957 against the Tigers.78 At season’s end, despite his sore arm, he joined barnstorming teams in Panama, the Dominican Republic, Mexico, Texas, and the West Coast. In Waco, Black and his black teammates went to a segregated movie theater. To demonstrate the irrationality of racism, Black, speaking Spanish, convinced the theater manager he was Cuban and was allowed to sit in the all-white seating section.79

Black had lost the velocity on his fastball, and lost his confidence, and players teed off on him. He pitched seven games and 12 2/3 innings for the Senators, giving up 22 hits, losing one game, and ending the season with a 7.11 ERA. His last major league outing was on September 11, 1957 against the Tigers.78 At season’s end, despite his sore arm, he joined barnstorming teams in Panama, the Dominican Republic, Mexico, Texas, and the West Coast. In Waco, Black and his black teammates went to a segregated movie theater. To demonstrate the irrationality of racism, Black, speaking Spanish, convinced the theater manager he was Cuban and was allowed to sit in the all-white seating section.79

When he returned his Senators contract unsigned, the team gave him his unconditional release on November 25, 1957. He could not endure more cortisone shots to relieve his pain, but he was unwilling to undergo an operation.80 At 33, his professional baseball career was over.

For the next six years — from 1957 through 1963 — Black taught physical education and coached baseball at the junior high school and high school levels in Plainfield, his hometown. Black’s students were a roughly equal mix of black and white young people, although he was one of the few black teachers in the school district. Black was a popular teacher and a stern disciplinarian, well known for his after-school “happy hour” sessions of tough conditioning exercises and calisthenics for students who did not take his gym classes seriously.

While teaching, he took graduate classes in education at Rutgers University and Seton Hall University, but didn’t complete his master’s degree, as he had hoped to do.81 As a teacher, Black earned about $4200 a year. To make extra money, he worked part-time in a local department store and sold encyclopedias. He occasionally pitched for several local semipro teams and sometimes pitched batting practice for major-league clubs. He organized an integrated barnstorming team, Joe Black’s All-Stars, that played in towns across New Jersey and Pennsylvania.82 He also ran Plainfield’s Optimist Baseball League for 13 to 15 year old boys, insisting that every player, regardless of talent level, play at least two innings each game.83

Black enjoyed teaching, but he had alimony and child support to pay and he was not earning enough to provide for himself and his family. Greyhound threw him a lifeline. He worked for the company from 1963 to 1987, much longer than he played professional baseball.

In 1961, six years after the Montgomery bus boycott, Americans watching television saw black and white civil rights activists being pummeled by white racist thugs as they exited from buses they sought to integrate as part of the Freedom Rides.

As the nation’s best-known bus line, Greyhound became associated with segregation in the eyes of the black community. To address this image problem, Greyhound began a recruitment effort to hire more African American employees, including drivers and sales executives. It also began a series of advertisements showing black and white passengers sitting in the same sections of buses.84

In 1962, Greyhound recruited Black to represent the company to black communities and let them know that Greyhound did not condone racist violence or segregation, or discriminate in hiring black employees.

In September 1963, Black moved to Chicago, home of Greyhound’s headquarters, to become director of special markets. By 1967, he was promoted to vice president of special markets for the parent company, Greyhound Corporation. When Greyhound moved its headquarters to Phoenix in 1971, Black moved there as well.

Black did a great deal of traveling, speaking to community groups, churches, schools, colleges, corporate seminars, and other organizations around the country.

Although his implicit message was that Greyhound was a good corporate citizen, his explicit message was to encourage parents to push their children to do well in school and to tell young people that education and hard work was the path out of poverty and into the middle class.

On behalf of Greyhound, Black developed local Woman of the Year and Father of the Year awards, given to people who helped improve their communities. Black would arrive to deliver a speech and give out the awards. Black also invited black professionals to talk to local young people about their educational and career trajectories. He organized seminars for young people about drug and alcohol abuse. He also helped black people get jobs with Greyhound. He got Greyhound to donate to black colleges and establish college scholarships, purchase goods from minority-owned businesses, and open accounts with local black-owned banks.85 To keep his hand in baseball, he persuaded Greyhound to sponsor an award for the players who led each league in stolen bases. Black presented the award every year.

Black acknowledged that for many years, “I accepted the rewards of the [civil rights] Movement passively, which wasn’t exactly paying one’s dues.” After meeting Martin Luther King he learned “how much greater the Movement is than the individual.” He committed himself “to extend my hand, to help black people understand our responsibilities, within our community, during our quest for equality of opportunity — and to help de-emphasize hate.”86 Black was one of many athletes and entertainers who attended the 1963 March on Washington, and three years later, at the invitation of Rev. Jesse Jackson, he joined pickets in front of Chicago stores that refused to hire or promote black employees. When King was murdered in 1968, Black flew to Atlanta and served as an usher at the funeral at Ebenezer Baptist Church.87

In 1972, after Jackie Robinson had become partly blind and close to death from diabetes, Black pressured Commissioner Bowie Kuhn to honor Robinson for breaking baseball’s color barrier 25 years earlier. Kuhn invited Robinson to throw out the first ball before the second game of the World Series in Cincinnati on October 15. Robinson used the occasion to criticize baseball for its slow racial progress.88 After Robinson died nine days later, Black was one of the six pallbearers at his funeral.89

Between 1969 and 1985, Black wrote a syndicated column, “By the Way,” that was published in Ebony and Jet magazines and about 40 black newspapers, including the Chicago Defender and Pittsburgh Courier. Each column included his photograph and was always signed “Joe Black, Vice President, The Greyhound Corporation.” He also recorded his columns for broadcast on over 50 radio stations serving black listeners.90

In his speeches and columns, Black acknowledged the harsh realities of racism, and expressed support for the civil rights movement in overturning barriers, but he also put much of the onus on the black community.

In 1979, he told a newspaper columnist that his message to black audiences was that “the social revolution is over. We accomplished what we set out to do. Now we must take advantage of each new opportunity that is presented.”91

Black was like a stern parent. He stressed the importance of education, hard work, ambition, respect for women, the responsibilities of black fathers, the problem of street crime and violence within black communities, the need for more black-owned businesses, the centrality of religious faith, the necessity for black Americans to participate in civic and community life, the need for graduates of black colleges to donate to their alma maters to help them thrive, and to take full advantage of the new voting rights laws.

In one column, Black wrote, “Yelling words and mouthing phrases like ‘Black Power,’ ‘Soul,’ or ‘black is beautiful’ can’t erase the problems in the ghetto. What can erase them are the things we can do to help our young people understand the true meaning of ‘intellectual power.’ If they learn, they’ll have a better chance to earn.” He encouraged parents to visit their kids’ schools, talk with the teachers, get involved with the PTA, and participate in neighborhood activities.

As he explained in his autobiography, “The ‘system’ is designed to allow some Black people to ‘escape’ from their socio-economic deprivation. And for reasons, not known to me, I was designated as one of the chosen few.”92 Black’s main message — which both reflected his personal feelings and was in line with the ideology of big corporations like Greyhound — focused on black self-help. He emphasized the importance of “educational preparation, pride, initiative, loyalty, and respect.”93

These values may have reflected mainstream attitudes in the black community, but some black activists believed that Black was “blaming the victim.” He was occasionally labeled an “Uncle Tom” or an “Oreo” (black on the outside, white on the inside).

Black’s educational background, hard work, and high salary didn’t immunize him from the reality of racism. When he interviewed Black for The Boys of Summer, Roger Kahn asked him why he lived on Chicago’s far south side, a predominantly black neighborhood a long way from his job at Greyhound’s downtown headquarters, when he could afford a more fashionable neighborhood. Black explained that he and his wife had once sought to buy a home in a development in the Chicago suburb of Lombard that included a pool, tennis courts, and a community social hall.

The sales manager asked Black where he worked. “The Greyhound Company,” Black answered. “What are you? A driver?” the sales manager asked. After Black handed him a card showing that he was a vice president, the sales manager asked, “What do you make?” Black said he, “Put down in excess of thirty five thousand dollars a year.” The amount put him at the upper end of the middle class. The sales manager asked Black if his job required him to do a lot of traveling and Black explained that he was often on the road. The sales manager said, “Well, you certainly earn enough, but if you travel, I can’t encourage you to buy. We don’t let anyone use the recreation room until they’re eighteen, and some of these seventeen-year olds, pretty husky fellers by the way, are kicking up a fuss. Rebelling. Throwing stones. Acting up. Now, Mr. Black, it certainly would be a terrible thing if these white seventeen-year-olds threw rocks through the window of your thirty-two-thousand dollar house, possibly injuring your wife while you were traveling and not here to protect her.”

Black’s white friends offered to buy one of the houses and then sell it to him — a tactic that was often used by civil rights groups seeking to integrate housing developments. Black refused. “Like hell. Something like that happens to you every day in your life if you’re black.”

As Black told Kahn, “There are plenty of places where, if a black man wants to live there, he has to fight a war.” Black didn’t want to fight a war. As Kahn wrote, “he has adjusted to bigotry, without accepting it.”94

Black had a wide network of friends among celebrities in show business, sports, politics, and business. One was Bill Cosby. In 1991, Cosby invited Black and Frank Robinson to appear on an episode of The Cosby Show, portraying former Negro League players reminiscing about their former teammates and rivals.95

As an expression of their common support for education as a means of upward mobility, Cosby headed a fundraising event in 2006 at Morgan State to raise money for the Joe Black Endowed Scholarship for Aspiring Teachers.96

Black retired from Greyhound in 1987, at age 63, after his daughter Martha Jo graduated from high school.

In 1989, soon after he became Baseball Commissioner, Bart Giamatti hired Black to talk with players about their futures. Black played at a time before the players union had freed players from the reserve clause. This gave rise to sports agents and huge salaries. By 1990, the minimum MLB salary was $100,000; the average was $597,537. The harsh reality was that the average player spent only five years in the big leagues, but few gave much thought to managing their money and planning for life after their playing days were over. Black visited players to discuss these matters, urging them to meet with financial planners to help invest their earnings wisely, and to go back to school in the off-season to complete their educations. But he quickly became discouraged because players showed little interest. “Ninety percent of them don’t think about that. They all think, ‘I’m going to play until the day I die.’”97

If Black couldn’t help contemporary players plan for their futures, he could help former players who were down on their luck. In 1986, a group of former major league players (led by Joe Garagiola and Ralph Branca) created the Baseball Alumni Team (later renamed the Baseball Assistance Team) to identify and help former players who couldn’t pay their rent or mortgage, utility bills, medical bills, or for a proper funeral for a spouse. Black, who became one of BAT’s vice presidents, would hear about an indigent ex-player or his widow and often make a personal visit to assess their situation and offer support. Some of them were players (or their widows) that Black had played with or against. Black drew on his network of retired players, and traveled to spring training camps to raise money for the BAT fund among current players. Some made significant contributions but he was saddened that others with multi-million salaries refused to help.

In 1992, Black urged Commissioner Fay Vincent to compensate living Negro Leaguers, most of whom never got the opportunity to play in the majors. Some also faced hard times. “These men don’t want charity, but they should be included in the Players Association medical plan,” Black said.98 Vincent asked Black and Len Coleman (a former football star at Princeton and former commissioner of New Jersey’s Department of Community Affairs) to recommend a plan. They suggested that those who played in the Negro Leagues before Robinson joined the Dodgers in 1947 should be eligible. In 1993, MLB gave 39 Negro League veterans and their spouses lifetime health insurance.

But it took a lawsuit by former Negro League and Boston Braves star Sam Jethroe to force MLB to deal with the problem that most former Negro League players lacked the full four years in the majors required to be eligible for a pension. A federal judge dismissed the suit because the statute of limitations had expired. But Chicago White Sox chairman Jerry Reinsdorf convinced other owners to set up a special fund to provide annual payments of $7,500 to $10,000 to 85 former Negro League players who had also played at least one day in the majors. Coleman, by then NL president, appointed Black to chair the committee administering the pension plan, which began in 1997. In 2004, two years after Black died, Commissioner Bud Selig expanded eligibility for the program to 27 other players who spent at least four years in the Negro Leagues but who never played in the majors.99

Black became a well-known figure in Phoenix. He did a lot of charity work in the area, serving on the boards of the local Big Brothers organization, the Salvation Army, the National Minority Junior Golf Scholarship Association, and a member of the local Kiwanis Club. He was also in demand as public speaker.

In 1993, soon after MLB awarded Phoenix a new franchise, the new team — the Arizona Diamondbacks — hired Black to serve as its community affairs representative. He was a regular in the Diamondbacks’ dugout during batting practice and in the press box and regularly attended major leagues games around the country.

Black was sitting near the Marlins dugout during seventh game of the 1997 World Series. With the Indians ahead 2-0 in the seventh inning, the Marlins’ Bobby Bonilla was in the on-deck circle, waiting to bat against Cleveland’s rookie pitcher Jaret Wright. The youngster was pitching a one-hitter. Black called Bonilla over and told him about pitching to Mickey Mantle in the seventh game of the 1952 World Series. Black got Mantle out twice by pitching him inside but when Mantle came to bat for the third time in the sixth inning, he adjusted his batting stance by stepping back in the batter’s box. Black didn’t notice and Mantle smashed a home run. Forty-five years later, Black urged Bonilla (4 for 26 in the series), to learn from Mantle’s example. Bonilla followed his advice, stepped back in the batter’s box, and hit a homer. Bonilla glanced over at Black as he rounded third base. The Marlins eventually won the game (and the World Series) in the 11th inning. 100

Many people recounted Black’s generosity. During spring training in 1955, when Black was struggling to maintain his place on the Dodgers’ roster, he befriended Sandy Koufax, then a rookie. Many Dodgers resented Koufax because, as a “bonus baby,” he was guaranteed a place on the roster irrespective of his experience or talent. The fact that he was Jewish compounded their hostility. “I was shunned by every player on the team except one. Joe Black came over to me, put his arm around me, and said, ‘Come on, kid, I’ll show you the ropes.’ We became great friends for life even though Joe was traded to Cincinnati in the middle of the season. He was there for me in my time of need.”101 According to his biographer, “Koufax never forgot Joe Black’s kindness.”102

Deeply religious and a regular church goer, Black didn’t smoke or drink, but when his playing days ended he ate to excess and by his 60s had ballooned to close to 300 pounds. Although he was a public figure with many friends, he described himself as a “homebody” with little appetite for parties and the social whirl.103 Despite his strong belief in family, Black was a failure as a husband. He was married seven times. “My marriages didn’t work because neither party worked hard enough for them to work,” he explained in his autobiography.104

Black had two children — Joe Frank Black (known as Chico), born May 26, 1952, and Martha Jo, born July 5, 1969. He took parenting responsibilities seriously and was a devoted father. When he and Martha Jo’s mother divorced, Black fought for and won custody of his five-year old daughter at a time, 1975, when courts rarely granted custody to fathers. As his daughter wrote in her memoir, Joe Black: More Than A Dodger, Black “went to every PTA meeting. He’d tell my teachers, ‘Hi, I’m Joe Black, I’m Martha Jo’s father. If there’s any problem, you call me.’ My dad was very instrumental in everything that I did. I loved my mother, but my father was a great parent.”105 She recalled, “The best part of my dad was that he raised me as a single parent in Paradise Valley, Arizona.”106 Martha Jo works in marketing for the Chicago White Sox. Joe (Chico) Black works for MAAX Industries in Arizona.

Black was inducted into Morgan State’s Sports Hall of Fame. He received honorary degrees from Shaw College in Detroit (1974), 107 Central States University (1977),108 and Morgan State (1983). 109 In 1981, Black received the Distinguished Broadcaster Award from the Academy of Professional Broadcasters for “influence on the minds and lives of young Black Americans” through the radio broadcasts of his “By the Way” columns.110 In 1987, Coretta Scott King bestowed Black with the Martin Luther King Distinguished Service Award at a ceremony in Atlanta.111 That same year, he was honored by the National Association for Sickle Cell Disease for his work as a board member and for educating the public about the disease.112 In 1991, he delivered the commencement address at Miles College, an historically black institution in Birmingham.113 In 2001, he was inducted into the New Jersey Sports Hall of Fame.

Black died of prostate cancer on May 17, 2002 at age 78 at the Life Care Center in Scottsdale, Arizona. Memorial services were held in Phoenix and Plainfield, attended by hundreds of friends, family, and former teammates and students. In Plainfield, Barbara Hill sang one of Black’s favorite songs, “If I Can Help Somebody.”114 He wanted his ashes spread on the Plainfield High School baseball field. City officials refused to allow it, but his son Chico visited the diamond and scattered them there anyway.115

The honors continued after he died. Morgan State created the Joe Black Endowed Scholarship for Aspiring Teachers. In 2010, the Washington Nationals created an annual Joe Black Award given to a person or group that promotes baseball in Washington’s inner city. In 2002, the Arizona Fall League, where major league prospects hone their skills, named its annual MVP trophy for Black.116 The Arizona Diamondbacks named a room at Chase Field in his honor. In 2010, the Plainfield school board named the Plainfield High School baseball complex the Joe Black Baseball Field.117

Many writers describe Black as having risen “out of nowhere” to lead the Dodgers to the 1952 pennant. This is misleading. As Black told Roger Kahn, “I couldn’t go into organized ball until Jackie made it and the quotas let me, and if we want to get sad, we can think that I pitched my greatest games in miserable ball parks, in the colored league, with nobody watching.”118

But Black was not resentful. Throughout his life, he expressed appreciation for the opportunities he had to play MLB and to use that experience, plus his college education and hard work, as a springboard for his career as a teacher, in corporate America, and as part of the civil rights movement.

Black touched many lives in many ways. “Baseball was the least of what he did,” said his friend Jerry Reinsdorf.119 “He was a psychologist, a humanist, a businessman and, across his 78 years, a magnificent advertisement for America,” wrote Roger Kahn.120

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Cassidy Lent at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Giamatti Library and Research Center; Martha Jo Black; Larry Treadwell, Lucera Parker, David Alexander, and Paul Baker at Shaw University; Erika Gorder, Dory Devlin, Daniel Villanueva, Betsy Feliciano-Berrios, and Carissa Sestito at Rutgers University; Laurie Pine at Seton Hall University; Gary Fink; E.J. Krieger; Mike Long; Bill Nowlin; Jacob Pomrenke; and Alan Cohen.

This biography was reviewed by Donna Halper and Bruce Harris and fact-checked by Paul Proia.

Sources

In addition to the sources shown in the notes, the author used Baseball-Reference.com and Seamheads.com.

Notes

1 Carl Lundquist, “Dodgers Break Even With Giants on Joe Black’s Pitching,” Knoxville (Tenn.) News- Sentinel, September 9, 1952: 12.

2 Martha Jo Black and Chuck Schoffner, Joe Black: More Than A Dodger (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2015), 4.

3 Joe Black, Ain’t Nobody Better than You (Scottsdale, Arizona: Ironwood Lithographers, 1983), 21.

4 Black, Ain’t Nobody, 28.

5 “Achievement Records Set in PHS Gym,” Plainfield (NJ) Courier News, March 15, 1941: 15.

6 Hugh Delano, “The Inside Track,” Plainfield Courier News, June 17, 1960: 30.

7 Richard Goldstein, “Joe Black, Pitching Pioneer for the Dodgers, Dies at 78,” New York Times, May 18, 2002: A13, https://www.NYTimes.com/2002/05/18/sports/joe-black-pitching-pioneer-for-the-dodgers-dies-at-78.html; Milton Brown, “Gentleman Joe,” The Oracle, Fall 2017: 20, https://oppf12d.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Oracle-Fall-2017.pdf. This article is based on an interview Black did with Brown in 2000.

8 The team took the same name as a team in the Negro Leagues, but it was a different entity.

9 Black, Ain’t Nobody, 29-30.

10 “Black Yankees Trounce Marinos,” Plainfield (NJ) Courier-News, June 1, 1942: 12.

11 “Black Yanks Beat Brunswick Nine,” Plainfield (NJ) Courier-News, July 6, 1942: 13.

12 “Black Pitches No-Hit Game for the Yankees,” Plainfield (NJ) Courier-News, July 13, 1942: 12.

13 Brown, “Gentleman Joe,” 21.

14 Black, Ain’t Nobody, 34-37.

15 Black, Ain’t Nobody, 61-64.

16 Dick Clark and Larry Lester, editors, The Negro Leagues Book (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 1994); and http://www.seamheads.com/NegroLgs/player.php?playerID=black01joe; Because Morgan State didn’t have a baseball team, Black did not jeopardize his amateur status, according to the rules of the Central Intercollegiate Athletic Association, the athletic conference of historically black colleges.

17 Black, Ain’t Nobody, 39; “Joe Black, PHS Great, Stars with Army Nine,” Plainfield Courier News, August 22, 1944: 11.

18 Black and Schoffner, Joe Black, 145.

19 Roger Kahn, The Boys of Summer (New York: Harper and Row, 1971), 278.

20 Black, Ain’t Nobody, 41-42.

21 “Saracens to Face Carters A.C. For City Independent Grid Title Thursday at Green Brook,” Plainfield (NJ) Courier-News, November 24, 1943: 13.

22 “Joe Black, PHS Great, Stars with Army Nine,” 11; “Topeka Ball Club at Camp Crowder Sunday,” Neosho (Missouri) Daily Democrat, May 19, 1945: 3.

23 “Joe Black, PHS Great, Stars With Army Nine,” 11.

24 Black, Ain’t Nobody, 71-73.

25 “Star Quintets Play in Crowder Tourney,” Joplin (Missouri) Globe, January 10, 1946: 8A.

26 Goldstein, “Joe Black, Pitching Pioneer”: A13.

27 “Seeks Pro Career,” Plainfield Courier News, November 14, 1947: 23.

28 “Former PHS Star on S. American Nine,” Plainfield Courier News, November 13, 1947: 24.

29 Dick Clark and Larry Lester, 314; Larry Lester, Black Baseball’s National Showcase: The East-West All-Star Game (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2001), 348-349 and 440.

30 Black, Ain’t Nobody, 75-76; Black and Schoffner, Joe Black, 166.

31 Buzzy Bavasi, “The Real Secret of Trading,” Sports Illustrated, June 5, 1967, https://vault.si.com/vault/1967/06/05/the-real-secret-of-trading; https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/B/Pblacj103.htm.

32 https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/player.fcgi?id=black-001jos.

33 Black, Ain’t Nobody, 81.

34 Black and Schoffner, Joe Black, 172.

35 Black, Ain’t Nobody, 82.

36 Black, Ain’t Nobody, 76-79.

37 Black and Schoffner, Joe Black, 77.

38 Black, Ain’t Nobody, 85; Black and Schoffner, Joe Black, 38.

39 Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson: A Biography (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997), 245.

40 Black, Ain’t Nobody, 85; Black and Schoffner, Joe Black, 86.

41 Harold Parrott, “Inside Jackie Robinson,” The Sporting News, February 3, 1973: 31-32.

42 Black, Ain’t Nobody, 88-89; Black and Schoffner, Joe Black, 41.

43 Black, Ain’t Nobody, 94.

44 Harold Burr, “Dressen Orders Hit Drills For Rusty Flock,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, May 2, 1952: 16, https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1952/B05010CHN1952.htm.

45 https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1952/Kblacj1030011952.htm.

46 Neil Lanctot, Campy: The Two Lives of Roy Campanella (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011), 183; Gayle Talbot, “Joe Black Key to Dodger Hopes As Series Starts,” Nashville Banner, October 1, 1952: 20.

47 Black, Ain’t Nobody, 114; Black, More Than, 198-202; “Black’s Life Threatened: Dodger Ace Ordered to Stay Away From Polo Grounds,” New York Times, September 5, 1952: 20.

48 Black, More Than, 123.

49 Black, Ain’t Nobody, 104.

50 Black, Ain’t Nobody, 102; Roger Kahn, Into My Own: The Remarkable People and Events That Shaped a Life (New York: St. Martin’s, 2007), 281; Peter Golenbock, Bums: An Oral History of the Brooklyn Dodgers (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1984), 319. In Kahn’s version, Black knocked down two Reds hitters; in Golenbeck’s version, he knocked down seven of them. Black’s daughter Martha Jo discusses Black’s use of the brushback pitch in her biography, Joe Black: More Than a Dodger, on page 154. Black also mentions it in his autobiography, Ain’t Nobody Better Than You on page 102. He is clear that he used the brushback pitch as a weapon. The author has, in the text, quoted Black directly: “The singing came to a halt.”

51 Gayle Tablot, “Rookie Hurler Carries Brooklyn Hopes,” Deseret News and Telegram (Salt Lake City), September 30, 1952: 17.

52 John Drebinger, “Three Dodger Homers Beat Yanks in Series Opener, 4-2,” New York Times, October 2, 1952: 1.

53 https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1952/B10010BRO1952.htm.

54 https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1952/B10040NYA1952.htm.

55 Roscoe McGowen, “Brooklyn’s Hopes for Series Honors Ride on Trusty Arm of Joe Black Today,” New York Times, October 7, 1952: 36.

56 Arthur Daley, “Most Valuable Player?” New York Times, September 14, 1952: 2S.

57 Black, Ain’t Nobody, 135; Roscoe McGowen, “Roberts of Phils Takes 27th Game By Turning Back Dodgers, 9 to 7,” New York Times, September 25, 1952: 39.

58 John Drebinger, “Black of Dodgers and Byrd of Athletics Capture Awards as Rookies of Year,” New York Times, November 22, 1952: 18.

59 Arthur Daley, “Most Valuable Player?” New York Times, September 14, 1952: 2S.

60 Roscoe McGowan, “Dodgers 4-Year Run Paced by Jackie, Peewee,” The Sporting News, December 3, 1952: 15; John Drebinger, “Sauer Chosen Over Roberts and Black As Most Valuable in National League,” New York Times, November 21, 1952: 30; Arthur Daley, “A Question of Value,” New York Times, November 26, 1952: 30; Gayle Talbot, “Eastern Writers Fuming Over West’s Alleged Bloc for Sauer,” Herald News (Passaic, New Jersey), November 21, 1952:14.

61 Oscar Fraley, “‘Halt and Blind’ Picked MVP Awards,” Tucson Daily Citizen, November 22, 1952: 9.

62 https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/1952_National_League_Most_Valuable_Player_Award.

63 Black and Schoffner, Joe Black, 275.

64 In 1952, the Cy Young Award for best pitcher did not yet exist. It began in 1956.

65 In the AL, Bobby Shantz (24-7, 2.48), the ace of the fourth-place Philadelphia Athletics, captured the MVP. It was the first time since 1938 that both MVP awards went to players whose teams didn’t win the pennant. John Drebinger, “Sauer Chosen Over Roberts and Black as Most Valuable in National League,” 30, https://www.baseball-reference.com/awards/awards_1952.shtml#NL_ROY_voting_link.

66 Oscar Fraley, “Fraley Sour on Sauer’s Choice as Most Valuable,” Herald-News (Passaic, New Jersey), November 21, 1952: 16; Joe Black, Ain’t Nobody, 118.

67 Kahn, The Boys, 255.

68 Black and Schoffner, Joe Black, 155-56; here’s an example of Black’s Lucky Strikes column in 1953, http://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lcPCN/sn83045120/1953-07-11/ed-1/seq-5.pdf.

69 Black, Ain’t Nobody, 120-121. Black discussed how he lost confidence after he changed his pitching style in this 2002 videotaped interview: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pwcKjumM8ac.

70 Black, More Than, 296.

71 https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1954/Kblacj1030031954.htm; https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/b/blackjo02.shtml.

72 Roscoe McGowen, “Black and Roebuck of Dodgers Accept Terms for Next Season,” New York Times, January 6, 1955: 32.

73 Black, Ain’t Nobody, 128.

74 “Kretlow, Black Sold By Raniers,” Longview (Washington) Daily News, May 25, 1957: 3; Bruce Brown, “From the Sidelines,” San Bernardino Sun, May 31, 1957: 25.

75 “Joe Black Returns to the Dodgers,” Hartford Courant, June 22, 1957: 13.

76 Black, Ain’t Nobody, 130-131.

77 Rick Swaine, The Integration of Major League Baseball: A Team by Team History (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2009), 166-176.

78 https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1957/B09112WS11957.htm.

79 Black, Ain’t Nobody, 133.

80 Black, Ain’t Nobody, 139. From his early youth, after a friend died in the hospital, Black was fearful of doctors and hospitals. He refused to undergo an operation on his pitching arm which might have helped restore his fastball. He failed to get a check-up that might have diagnosed his prostate cancer before it spread too far and eventually killed him.

81 In 1958, Black took a graduate course in Health Education for Teachers at Rutgers University, according to a July 22, 2020 email from Carissa Sestito at Rutgers University. Black took two graduate courses — Educational and Vocational Guidance and Study of the Individual in Personnel and Guidance — at Seton Hall University during the summer of 1960, according to a July 1, 2020 email from Laurie Pine at Seton Hall University.

82 “Black’s Stars Play Tomorrow,” Plainfield Courier News, August 22, 1959: 11; “Joe Black Sparkles for All Star Team,” Plainfield Courier News, May 9, 1960: 24; Hugh Delano, “The Inside Track,” Plainfield Courier News, June 17, 1960: 30.

83 Black, Ain’t Nobody, 152; Jim Peoples, “Black is Still An Optimist in Baseball League and Work,” Plainfield Courier News, June 9, 1960: 32.

84 Edward Reilly, The 1960s: American Popular Culture Through History (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2003), 49.

85 Black and Schoffner, Joe Black, 261.

86 https://newspapers.library.in.gov/cgi-bin/indiana?a=d&d=INR19740504-01.1.2&e= — — — -en-20 — 1 — txt-txIN — — — –.

87 Black, Ain’t Nobody, 185 and 192.

88 Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson: A Biography (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997), 459.

89 Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson: A Biography, 460.

90 Source: Biography of Joe Black on the program for his memorial service in Phoenix in 2002.

91 Bob Quincy, “Fame and Fastball Faded by Message Remains,” Charlotte (N.C.) Observer, November 16, 1979: 12.

92 Black, Ain’t Nobody, 227.

93 Black, Ain’t Nobody, 241.

94 Kahn, The Boys, 265-266.

95 https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0547111/.

96 https://vdocuments.mx/alumni-news-fall-2006.html.

97 Black and Schoffner, Joe Black, 307.

98 Dave Anderson, “Sports of the Times: Here’s a Soda for Buck Leonard,” New York Times, June 1, 1992: C5, https://www.nytimes.com/1992/06/01/sports/sports-of-the-times-here-s-a-soda-for-buck-leonard.html.

99 Bill Nowlin, “Sam Jethroe,” SABR biography project, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/5f1c7cf9; N. Jeremi Duru, “Sam Jethroe’s Last Hit,” in Ron Briley, ed., The Politics of Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2010); N. Jeremi Duru, “Exploring Jethroe’s Injustice: The Impact of an Ex-Ballplayer’s Legal Quest for a Pension on the Movement for Restorative Racial Justice,” University of Cincinnati Law Review, Vol. 76, Spring 2008, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1114209; Larry Moffi and Jonathan Kronstadt, Crossing the Line: Black Major Leaguers, 1947-1959 (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1994); Howard Bryant, Shut Out: A Story of Race and Baseball in Boston (New York: Routledge, 2002); Anderson, “Here’s a Soda;” Brad Snyder, “Jethroe seeks legal victory in bid for baseball pension,” Baltimore Sun, April 22, 1995, https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/bs-xpm-1995-04-22-1995112081-story.html; “Lawsuit Dismissed,” New York Times, October 6, 1996: Section 8: 13, https://www.nytimes.com/1996/10/06/sports/lawsuit-dismissed.html; Murray Chass, “Pioneer Black Players To Be Granted Pensions,” New York Times, January 20, 1997: C9, https://www.NYTimes.com/1997/01/20/sports/pioneer-black-players-to-be-granted-pensions.html; Ronald Blum, “Negro League Players Gain Pension Eligibility,” Indiana (Pennsylvania) Gazette, January 20, 1997: 17; Philip Dine, “Negro Leaguers Who Played in the Majors Finally Win Pensions,” St. Louis Post Dispatch, January 24, 1997: 31; Jim Auchmutey, “‘He’s Our Jackie’: Sam Jethroe, The First Black Braves Play, at 79 Fights Barriers to a Baseball Pension,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, June 22, 1997: 85; Richard Goldstein, “Sam Jethroe is Dead at 83; Was Oldest Rookie of the Year,” New York Times, June 19, 2001: A21, https://www.NYTimes.com/2001/06/19/sports/sam-jethroe-is-dead-at-83-was-oldest-rookie-of-the-year.html; Stan Grossfield, “He’s Still Game: At 80, Ex Negro Leaguer Is Raising Five Children and Hoping for a Pension,” Boston Globe, March 31, 2004: 67; Brady Dennis, “Pay is for Player of Bygone Era,” Tampa Bay Times, May 18, 2004: 9; Gregory Lewis, “Negro Leaguers To Get Their Share,” South Florida Sun Sentinel, May 18, 2004: 40; Doug Gladstone, “MLB Isn’t Paying Pensions to Herb Washington and Other Persons of Color,” Bleacher Report, July 17, 2012, https://bleacherreport.com/articles/1261542-mlb-isnt-paying-pensions-to-herb-washington-and-other-persons-of-color.

100 https://sabr.org/latest/neyer-joe-black-bobby-bonilla-and-a-little-adjustment/; https://tht.fangraphs.com/winner-takes-all-which-was-the-best-world-series-game-seven/; https://medium.com/the-christian-counterculture/paying-forward-our-mistakes-a5589a1df3a2.

101 Steven Michael Selzer, Meet the Real Joe Black (New York: Universe, Inc., 2010), 152; Jane Leavy, Sandy Koufax: A Lefty’s Legacy (New York: HarperCollins, 2002), 66-67, 69-70.

102 Leavy, Sandy Koufax, 76.

103 Black, Ain’t Nobody, 231.

104 Black, Ain’t Nobody, 232

105 Black and Schoffner, Joe Black, 220.

106 Personal email from Martha Jo Black to Peter Dreier, June 1, 2020.

107 “Shaw College to Award Honors to 4,” Detroit Free Press, May 9, 1974: 37. Many articles and profiles of Black say that he received an honorary doctorate from Shaw University, a well-known historically black institution in North Carolina. At my request, Larry Treadwell IV (Shaw University’s Director of Library Services) and Paul Baker (the university archivist) searched but did not find evidence that Black was honored by that institution. Source: Email from Larry Treadwell, August 7, 2020, and phone call with Paul Baker, August 6, 2020.

108 “On Campus,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 16, 1977: 11.

109 https://commencement.morgan.edu/honorary-degrees/.

110 “Joe Black to Receive The Distinguished Broadcaster Award,” Carolina Times, April 18, 1981: 9, https://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn83045120/1981-04-18/ed-1/seq-9/.

111 “Greyhound Executive Picked for King Award,” Arizona Republic, December 14, 1986: 53.

112 https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1987-pt22/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1987-pt22-1-3.pdf.

113 “Cosby Tells Graduates to Advance Civil Rights,” Alabama Journal, May 13, 1991: 2.

114 Kara Richardson, “Mourners in Plainfield Recall Baseball Hero,” Bridgewater Courier News, June 2, 2002: A1; Harry Frezza, “Extraordinary Gathering Bids Farewell to Black,” Bridgewater Courier News, June 2, 2002: E1.

115 Black and Schoffner, Joe Black, 352.

116 Black and Schoffner, Joe Black, 352.

117 Jeremy Walsh, “Plainfield To Name Baseball Field After Joe Black, The First Black Pitcher to Win a World Series,” (Newark, N.J.) Star-Ledger, July 15, 2020, https://www.nj.com/news/local/2010/07/plainfield_to_honor_pioneering.html; Jeff Grant, “Plainfield Renames Field for Joe Black,” BCN, September 26, 2010; “Joe Black Ballfield Dedication Tomorrow,” Plainfield Today, September 24, 2010, http://ptoday.blogspot.com/2010/09/joe-black-ballfield-dedication-tomorrow.html.

118 Kahn, The Boys of Summer, 264.

119 Scott Merkin, “Black Was a Giant On and Off the Field,” MLB.Com, February 10, 2011.

120 Roger Kahn, “Hard Thrower, Soft Heart,” Los Angeles Times, May 18, 2002: 90, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2002-may-18-sp-kahn18-story.html.

Full Name

Joseph Black

Born

February 8, 1924 at Plainfield, NJ (USA)

Died

May 17, 2002 at Scottsdale, AZ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.