Pedro Ramos

Despite 100-plus big-league victories, a half-dozen straight workhorse campaigns of 200-plus innings tossed, and a crucial role in a historic mid-’60s American League pennant drive, Pedro Ramos’s small degree of diamond immortality will likely always rest upon two individual pitches tossed in the midst of an erratic 15-season sojourn. Both fateful deliveries came while he wore the uniform of his first and most prominent big-league club, the hapless Washington Senators (“first in war, first in peace, and last in the American League”). If one searches for an exemplar of a big leaguer for whom a combination of ill-timing and his own character flaws sabotaged both a promising diamond career and a reckless post-baseball personal life, Pedro Ramos Guerra — “The Cuban Cowboy” — stands as the unmatched poster boy.

Despite 100-plus big-league victories, a half-dozen straight workhorse campaigns of 200-plus innings tossed, and a crucial role in a historic mid-’60s American League pennant drive, Pedro Ramos’s small degree of diamond immortality will likely always rest upon two individual pitches tossed in the midst of an erratic 15-season sojourn. Both fateful deliveries came while he wore the uniform of his first and most prominent big-league club, the hapless Washington Senators (“first in war, first in peace, and last in the American League”). If one searches for an exemplar of a big leaguer for whom a combination of ill-timing and his own character flaws sabotaged both a promising diamond career and a reckless post-baseball personal life, Pedro Ramos Guerra — “The Cuban Cowboy” — stands as the unmatched poster boy.

The first and most celebrated of those memorable heaves resulted in a prodigious Mickey Mantle home run that remains one of the popular talking points of baseball’s post-World War II Golden Era decade. The second, coming four years later, earned for Ramos and a pair of his fellow Cubanos a small but durable footnote in baseball’s endless list of nostalgic trivia. The problem with those two isolated moments, however, is that they both capsulate and obscure a much larger colorful career of one of the most talented if inconsistent and ill-starred hurlers of the mid-20th century.

The fateful pitch to Mickey Mantle resulted in one of the most memorable blasts among the considerable list of Mantle tape-measure shots. The setting was the first game of a May 30, 1956, Yankee Stadium twin bill in which Mantle faced and terrorized two of his favorite victims, Ramos (12 career homers) and Camilo Pascual (11 lifetime blasts).1 Struck by an errant Ramos fastball in his first trip, Mantle stepped up a second time with the Yankees on the short end of a 1-0 score. He quickly knotted the count with a shot that came within approximately 18 inches of being the first ball ever to exit the cavernous ballpark on the fly. In the second game of the afternoon, again batting from the left side, Mickey tattooed Pascual with an only slightly less impressive 450-foot blast to the top of the right-center-field bleachers. The prodigious shot off Ramos would be later duplicated, if not overshadowed, by another off Kansas City right-hander Bill Fischer, that latter smash (on May 22, 1963) also striking the right-field third-deck façade and ricocheting back onto the playing field.

The second fateful pitch, this time to future manager Whitey Herzog, resulted in a delectable tidbit of 1960s trivia — an all-Cuban triple play. The setting was Washington’s Griffith Stadium, the teams involved were the hometown Senators and the visiting Kansas City Athletics, and the date was July 23, 1960. In the top of the third inning, with Washington holding a 3-1 lead and Kansas City threatening to cut the gap, outfielder Herzog stood at the plate with a full count, Jerry Lumpe rested on first, and Bill Tuttle was the baserunner at second. Herzog lined the next pitch straight into the glove of pitcher Ramos (one out); Ramos whirled and heaved to first baseman Julio Becquer (doubling up Lumpe for out number two); Becquer then tossed down to second where shortstop José Valdivielso tripled up the slow-footed Tuttle. Presto, a big-league feat never before or since duplicated, an all-Cuban triple play.

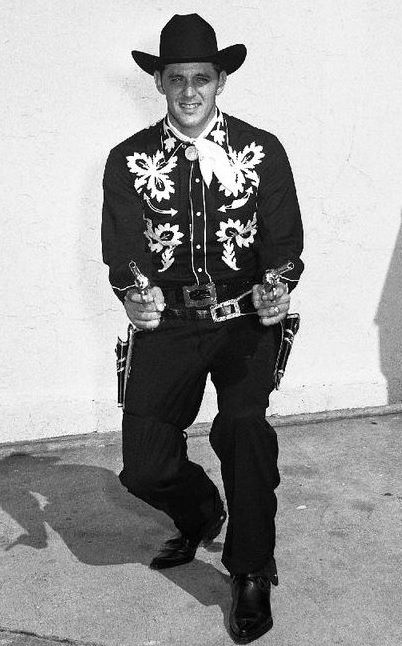

If the Mantle homer today maintains a rather unfair stature in Ramos’s more ample career, it admittedly does seem to fittingly symbolize “the good, the bad, and the ugly” aspects of the flashy Cuban’s 15-season big-league tenure. If Pedro Ramos did one thing more regularly and consistently than any of his contemporaries it was to serve up home-run balls. By most measures Ramos stands atop any potential list when it comes to surrendering mammoth blasts. During his own era Ramos (with a total of 315) fell considerably short of one-time career leader Robin Roberts (505); in the subsequent half-century numerous others have far outdistanced the Cuban in gopher ball numbers. Jamie Moyer (511 in both the National and American Leagues) is the current major-league record holder and Warren Spahn (NL, 434) and Frank Tanana (AL, 422) hold the individual league records; Ferguson Jenkins (484), Phil Niekro (482), and Don Sutton (472) have also posted near-record numbers that now dwarf the total Ramos reached. But in a study published in SABR’s Baseball Research Journal in 1981, Raymond Gonzalez clarified Ramos’s true stature as one of the top deliverers of long balls in all of major-league baseball’s extensive history. The far truer picture emerges when one examines ratios and not mere raw numbers, and here Pedro Ramos leaps to the top of the rankings with a circuit blast allowed in every 7.48 innings worked; this frequency outpaces the vulnerability numbers of Moyer (1/7.86), Roberts (1/9.29), Jenkins (1/9.30), Tanana (1/9.34), and other close rivals for this unwanted title. Ramos (the self-imagined gunslinger) truly loved to challenge the league’s strongest hitters and he often came out a loser.

The triple-play-launching pitch in 1960 is also not without its elements of symbolism, since Pete Ramos was indeed one of the centerpieces of the 1950s-era Cuban invasion of American League baseball in Washington and eventually far beyond. Latin American big-league recruits were indeed a rarity before the midpoint of the 20th century and of course race and the big-league color ban were prominent reasons for the shortage. Of the 44 true Latinos to reach “The Show” before Jackie Robinson (all of them white or perceived to be white), 38 hailed from Cuba, two apiece from Puerto Rico and Mexico, and one each from Colombia and Venezuela. The only legitimate big-league star had been Cuba’s Dolf Luque (27-game winner with Cincinnati in 1923), while eventual Hall of Famers like Martin Dihigo, Cristóbal Torriente, and José de la Caridad Méndez (Cubans all) joined countless North American blacks in the shadow world of the barnstorming Negro leagues circuit. The floodgates began to crack open with the arrival of 22 Cubans in the 1940s, a dozen of them cup-of-coffee journeymen bagged by Havana-based scout Joe Cambria for Clark Griffith’s cellar-dweller and penny-pinching Washington club. By the time a handful of truly legitimate pitching prospects begin to trickle into Washington from Havana in the early ’50s — in the persons of Conrado Marrero (1950), Sandalio Consuegra (1950), Julio Moreno (1950), and finally Pascual (1954) and Ramos (1955) — the Latino presence was finally as noticeable as the increasing numbers of promising African-Americans trailing Robinson into Brooklyn, New York (Giants), Cleveland, and Boston (Braves).

Ramos never reached the true stardom eventually found by his Havana-born teammate Camilo Pascual, an eventual American League pacesetter in complete games (1959, 1962, 1963), shutouts (1959, 1961, 1962), and strikeouts (1961, 1962, 1963), and a two-time 20-game winner (1962, 1963). Arguably this was in large part due to raw talent, but it also had a good deal to do with mere timing. Pascual (a double-figure winner five straight times in Washington) never blossomed until the transplanted Twins developed some formidable offensive support paced by the young tandem of Harmon Killebrew and Bob Allison. A first year in the new Midwestern surroundings found Pascual finally overhauling Pistol Pete with a respectable 15-16 ledger and a first strikeout crown (Ramos was an 11-game winner but lost a league-worst 20). But when things began to spike in Minnesota the following season Ramos never benefited, being shipped out on the eve of Opening Day to an equally inept Cleveland ballclub.

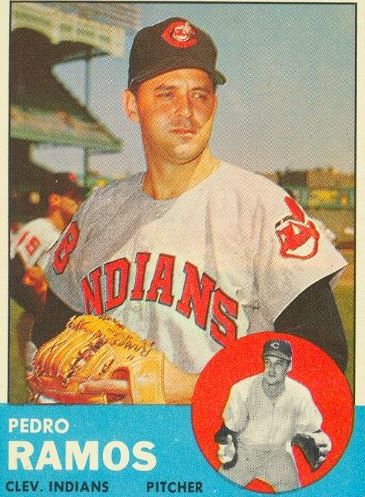

Despite the sometimes depressing numbers of his first half-dozen seasons, Ramos was never as bad as those raw numbers and the record pace of near-20-loss seasons might seem to suggest. He won more than Pascual in Washington despite one less season, compiling a six-year 67-92 ledger compared with Camilo’s 57-84 mark, and also logged more complete games (49 vs. 47) but trailed in strikeouts (566 vs. 891). On given days the hard-throwing Cuban Cowboy could be as dominant as anyone, and he even managed to flirt with a near no-hitter at the tail end of his tenure in Washington. If he was wild early on, his strikeout totals eventually became impressive. By 1958 his K’s rose to 132 (against only 77 free passes) and the favorable K/BB ratio improved further still in later years in Cleveland (169/41 in 1963) and New York (21/0 in the final month of 1964). In the late 1950s he also equaled teammate Pascual as a true ace on their Cienfuegos team back home in the Cuban winter circuit.

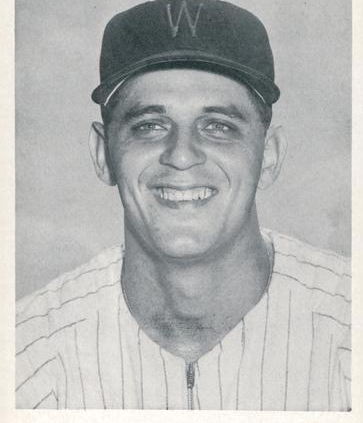

Obviously Ramos was plagued in his early big-league years by the weak-hitting and sloppy-fielding teammates who surrounded him, as of course was teammate Pascual. And Ramos also likely suffered from being rushed to the big leagues by a desperate Washington club strapped for young quality arms that could eat up large amounts of innings. Recommended for promotion to the big club by Cambria after only two minor-league campaigns (33 appearances as an 18-year-old with Class D Morristown and 43 outings as a 19-year-old with three different clubs at the C and B levels), the raw youngster experienced his first big-league game on April 11, 1955 — two weeks short of his 20th birthday. If a 5-11 rookie campaign was not eye-popping, it did suggest considerable future promise, as the latest Cuban to staff the Washington pitching arsenal posted a break-even mark (5-5) against the league’s top four clubs and fashioned a two-hit shutout of the third-place White Sox. He also logged three scoreless relief appearances against the champion Yankees and was already the staff workhorse with a club-leading 45 appearances, supplanting 1954 rookie sensation Pascual in that department.

The eldest child of Ramón Ramos and Sofia Guerra, Pedrito (Little Pete) was born in Cuba’s westernmost, tobacco-producing province of Pinar del Río on April 28, 1935. The actual birth location was the tiny village of Corojo in the municipality of San Luis, a district of Pinar del Río Province. The elder Ramón Ramos was reputedly a tobacco farmer known familiarly in the native village as Ramón Frias (Cold Ramón), and like his father before him, the eldest son would always be known to neighbors by a familiar descriptive nickname — Pedrito — somewhat ironically applied given the youngster’s already noticeable athletic build by his early teenage years. Four siblings followed Pedro into the Ramos homestead: three brothers and a young sister Ramona, who old-timers in Pinar still remember as a statuesque and striking beauty. Two of the younger Ramos offspring were named Ramón (nicknamed El Gallego) — remembered as a talented pitcher and first baseman in his own right — and Cristóbal, the only non-ballplaying brother. A third sibling remembered today by locals only by his nickname (El Pitcher) also distinguished himself on local baseball fields.

A rural upbringing in Cuba’s late-1930s and early-1940s version of the American Wild West would later provide a self-styled trademark persona and be often capitalized on as the strikingly handsome professional ballplayer adopted an off-the-field alter ego as a gun-toting cowpuncher, both on his native island and stateside. In Washington, Cleveland, and New York the Cuban hurler loved to dress in lace-trimmed black cowboy duds, taking on a striking resemblance to two of his movie-screen idols, the Lone Ranger and Bill “Hopalong Cassidy” Boyd. During a brief late-career surge in the media center that is New York, a number of publicity shots of Pistol Pete Ramos in full western regalia would appear in print.

In a brief character portrait of the star pitcher for the pages of Baseball Digest, Washington Post writer Bob Addie reported that Ramos improved his almost nonexistent English during early big-league days in Washington by watching his favorite Hollywood cowboy action movies. Addie also delighted in relating a charming tale of the pitcher’s first acquisition of a full cowboy suit, on a road trip to Kansas City.2 But the adopted gunslinger image eventually proved to have its dark side as well, especially in post-baseball days when gun-toting would become more of a profession than a hobby. But even while Ramos was an active ballplayer the adopted cowboy image sometimes encouraged reckless behavior. Author Mike Shannon (Tales from the Ballpark, 2000) quoted a report by Cleveland teammate Sonny Siebert that Ramos’s brief marriage to a Cuban beauty queen in the early ’60s came to a quick end when the hot-blooded pretend cowboy used his six-shooters to blast holes in the family television after he disapproved of his wife’s program choices.

In a brief character portrait of the star pitcher for the pages of Baseball Digest, Washington Post writer Bob Addie reported that Ramos improved his almost nonexistent English during early big-league days in Washington by watching his favorite Hollywood cowboy action movies. Addie also delighted in relating a charming tale of the pitcher’s first acquisition of a full cowboy suit, on a road trip to Kansas City.2 But the adopted gunslinger image eventually proved to have its dark side as well, especially in post-baseball days when gun-toting would become more of a profession than a hobby. But even while Ramos was an active ballplayer the adopted cowboy image sometimes encouraged reckless behavior. Author Mike Shannon (Tales from the Ballpark, 2000) quoted a report by Cleveland teammate Sonny Siebert that Ramos’s brief marriage to a Cuban beauty queen in the early ’60s came to a quick end when the hot-blooded pretend cowboy used his six-shooters to blast holes in the family television after he disapproved of his wife’s program choices.

Pedrito was making his reputation as an amateur pitcher by the time he reached his early teens, first performing for the Corojo village club in the provincial Free League (Liga Libre) in the early 1950s, and then for a club named La Opera that represented Pinar del Río Province in the national Amateur Athletic Union league. At 17 he was inked to a Senators contract (apparently by the ubiquitous Papa Joe Cambria) for a reported $150 bonus. The early signing of the raw teenager not only meant that Ramos would head off to the low-level North American minor leagues before ever pitching professionally in his homeland. It also was part of a disturbing trend that was by 1952 weakening Cuban baseball at all levels. The signing of such promising youngsters as Sandy Amorós (by the Dodgers) and Pascual, Ramos, and José Valdivielso (all by Washington) directly from the ranks of the juveniles (youth leagues) meant that the cream of Cuba’s best young stars would never get to showcase their talents in the wildly popular island-wide AAU circuit.

The young and unseasoned Ramos was one of the more profitable signings for Washington Senators birddogs roaming the Cuban countryside in the late 1940s and early ’50s under the direction of Joe Cambria. Those scouts and Cambria in particular pulled in quite a haul but found few true diamonds in the rough. And the fact that prospects like Pascual and Ramos survived at all had little to do with careful grooming and seemingly everything to do with the survival instincts and native toughness of the young Cubans. Dumped unceremoniously in Tennessee with almost no English and less in the way of worldly sophistication, the brash youngster showed enough pluck to survive with a 7-6 ledger (and a soaring 6.26 earned-run average plus one homer allowed for every nine frames worked) for the Class D Morristown club. A final teenage year was divided between Hagerstown (Class B Piedmont League) and a pair of Mountain States League ballclubs (Kingsport and again Morristown, now Class C), and more promise was flashed with an overall 19-6 mark and a far more respectable 3.26 ERA. Such limited low-level seasoning and the fact that Pete Ramos was still under 20 when he finally arrived prematurely in Washington is rationale enough to explain a solid if less than spectacular American League rookie campaign. And if the 1955 debut season was far from a disaster, the picture improved rapidly despite the drawbacks of laboring for a basement-dwelling Washington outfit. Pete would log more than 150 innings his second season (tops for a Washington right-hander), win in double figures, and climb above the .500 level with his 12-10 ledger. A year later he paced the club in innings pitched.

Across five final seasons of Washington tenure for the original Senators, Ramos was a genuine workhorse who won in double figures each of those campaigns. The downside was that he also rang up double-figure loss totals for each of those years. In three of those five campaigns Ramos actually paced the American League in total losses, dropping 18 in both 1958 and 1960 and 19 in 1959. He might have had the ignoble honor four years running had not teammate Chuck Stobbs dropped 20 (to Ramos’s 16) in 1957. Of course it has to be remembered that Ramos was the number one starter (ahead of Pascual and southpaw Stobbs) on a lackluster team that finished seventh once and occupied the eighth-place basement on the other four occasions. Pascual (eventually twice a 20-game winner once the club got to Minnesota) won fewer games than Ramos in all but the final two of those futile twilight seasons in the nation’s capital.

A more useful measure of Ramos’s early struggles than those won-lost ledgers was the elevated (sometime even astronomical) numbers for home runs surrendered and for hits and runs allowed. In the hit department his totals soared above 230 in each of his final five summers with the franchise. He also walked more than he struck out in his first two big-league campaigns. But his control soon improved and Ramos — who loved to challenge hitters pitch after pitch — doggedly learned to throw strikes consistently. The new talent for getting his fastball down the middle of the plate might go a long way to explaining the exploding home run totals. The reckless Cuban “launching pad” once gave up a single-season league record 43 circuit blasts (in 1957, long since broken), a major step toward his eventual dishonorable distinctions as big-league baseball’s all-time long-ball frequency leader.

Among the many footnotes dotting his career, Ramos would have the distinction of pitching the final game for the Griffiths’ Senators before the club finally pulled up stakes for greener grass in Minneapolis. On October 2, 1960, the Cuban ace went the distance before a sparse Griffith Stadium crowd (4,678) only to drop a 2-1 heartbreaker to Baltimore’s Milt Pappas. All too characteristically, the defeat came when Ramos allowed a solo shot in the eighth inning off the bat of light-hitting outfielder Jackie Brandt. Ramos also corralled the starting assignment for the Minnesota Twins franchise opener on April 11, 1961, enjoying better luck in logging the first-ever club victory with a 6-0 whitewashing of New York in Yankee Stadium. The new environs soon proved a true boon to fellow Cuban Camilo Pascual, who quickly translated better offensive support from Killebrew, Versalles, Allison, Oliva, and company into a complete career transformation. Pascual was soon the best right-hander in the American League, leapfrogging over Ramos as the new staff ace.

While Pascual soared in novel surroundings, things unfortunately didn’t get much better in Minnesota for Ramos. The landmark Opening Day success against his favorite cousins, the Yankees, sadly proved to be something of a season’s highlight. In his single summer with the newly renamed and revamped Twins, the former Washington ace again won in double figures (11), yet also lost a career high 20 and further solidified his rank as the league’s most willing victim. It was the fourth time Ramos was the American League’s pacesetter in defeats. The 27-year-old Cuban — still in his prime chronologically — seemed to offer living proof of an old adage: You had to be a pretty damn good pitcher to survive long enough in the big time to drop 18-plus outings on no fewer than four different occasions and still hold considerable value as a durable starter. But that value had by September 1961 been all but extinguished in Minnesota.

Then a corner was finally turned when Ramos received a new lease on life just before Opening Day of 1962. The expendable if durable right-hander was traded to the Cleveland Indians on April 2 for flashy Puerto Rican first baseman Vic Power and third-year pitcher Dick Stigman. The Twins were betting on Power to be the missing element in building a pennant challenger, and if it didn’t turn out quite that way immediately the trade did largely go Minnesota’s way. Stigman outstripped Ramos’s victory totals over the next couple of years and Power tutored blossoming Cuban import Tony Oliva before departing Minnesota in 1964. For Ramos it was little more than a backward move since the Twins continued to surge as contenders while the Indians continued to languish in the second division.

Won-lost columns more or less evened out for Pistol Pete during his two-plus seasons in Cleveland. In the second year he even managed to climb above water for only the second time in his career with a 9-8 posting. But the biggest moment on the lakefront ironically came not with his deliveries on the hill but with a swing of his bat. In the opener of a Municipal Stadium twin bill on May 30, 1962, he smashed two round-trippers, one a grand slam, off feeble offerings from Baltimore’s Chuck Estrada, thus accounting for five RBIs in the 7-0 whitewashing. Little more than a year later came another memorable slugging feat. On July 31, 1963, he joined with a trio of teammates (Woody Held, Tito Francona, and Larry Brown) to stroke the second of four consecutive home runs. The feat made the Indians only the second big-league club to string together four straight homers, and the Los Angeles Angels’ Paul Foytack the first hurler ever to yield four straight circuit blasts in an inning. It was one of two round-trippers in the game for Ramos, who not so surprisingly also yielded a pair of homers himself in the 9-5 victory over Los Angeles.

Despite such occasional power displays, the Cuban right-hander was never truly a major threat at the plate, as indicated by his anemic lifetime sub-Mendoza-Line batting average (.155). The free-swinging hurler was once cut down waving at pitches outside the strike zone on eight straight occasions. But Pete did provide some rather notable bench utility for all six of his big-league employers, utility resulting from his running speed if not from his bat speed. His running prowess actually became a colorful sidelight to his pitching career as early as the first seasons in Washington, where he was frequently used as a late-inning pinch-runner. And he garnered press attention over the years by repeatedly challenging Mickey Mantle (who repeatedly declined) to pregame foot-racing exhibitions. Washington Post writer Bob Addie did once report (Baseball Digest, March 1960) on an actual challenge match in Orlando’s Tinker Field during spring training in 1959 when the Washington speedster outlegged the Phillies’ Richie Ashburn by eight yards over a 70-yard outfield course. Reportedly the entire Washington and Philadelphia baseball press had wagered heavily of the outcome.

It would be hard to find a better single outing by Ramos than that reported July 1963 encounter with Foytack and the Angeles featuring not only Pistol Pete’s rare home run heroics but also a career-high total of 15 strikeouts in 8 1/3 innings. Yet an earlier masterpiece in Washington might vie for recognition as Ramos’s best single day in a big-league uniform. On July 20, 1960, in Detroit’s Briggs Stadium the then-25-year-old righty dominated the Tigers’ lineup during a complete-game one-hit, 5-0 whitewashing. On that occasion Ramos was robbed of the small degree of baseball immortality attached to a big-league no-hitter when Detroit slugger Rocky Colavito bounced a single in the eighth inning just beyond the outstretched glove of shortstop and fellow Cuban José Valdivielso. The final accounting was nine enemy K’s, four walks, and one additional Detroit baserunner via a hit batsman. Yet despite this rare brush with Cooperstown, at the end of the day Ramos’s midseason record still stood at an all-too-familiar six victories against 10 defeats (en route to a league-leading 18 defeats by season’s end).

If his career never got entirely untracked in Cleveland, Pete Ramos was nonetheless about to experience a second — this time far more miraculous — career renovation by the late stages of the 1964 campaign. In a tight pennant race heading down the stretch, the New York Yankees handed Ralph Terry and Bud Daley (as players to be named later) and $75,000 to the Indians in order to obtain Ramos for what they hoped would be some late-season bullpen support. It turned out to be one of the best deals (of so many during those New York dynasty years) that the Yankees ever made — one ranking right up there with several similar celebrated acquisitions of fading veterans like Johnny Mize (1949), Johnny Hopp (1950), Johnny Sain (1951), and Enos Slaughter (1954, 1956).

A lifelong starter, Ramos experienced a new life in his transformation into a bullpen stalwart with the American League champions. He suddenly and unexpectedly was able to produce some of the best and most consistent pitching of his career. Now a workhorse reliever instead of a workhorse starter, Ramos made 13 appearances in the final month for New York, striking out 21 in 22 innings without walking a single batter. It was a brilliant performance sufficient to lead New York to a fifth straight league title as the Bronx Bombers nipped the White Sox by a single game at the wire (with Baltimore but two games back). But Ramos didn’t receive much payoff for his stellar efforts (8 saves and a 1.23 ERA), which proved New York’s salvation during the stretch run. As a final-month addition he did not qualify for the Yankees’ World Series roster.

Such late-season brilliance did bring at least one bonus since it earned the now 30-year-old righty two more seasons in New York, where he eventually won eight overall and dropped 14 in 117 appearances, all but one as a reliever. But his roller-coaster career was now winding down and over the final four summers of the decade he spent the bulk of the time back in the minors. Traded to the National League Phillies before the 1967 campaign, he made but six starts there without a decision. Two years later, after toiling in Triple-A, he climbed back to the big leagues for brief additional stints, first with Pittsburgh and later with Cincinnati. He also returned to Washington with the expansion Senators under Ted Williams and made four appearances early in the 1970 season. That belated Washington reunion made him one of just seven players (along with Camilo Pascual, Don Mincher, Johnny Schaive, Roy Sievers, Zoilo Versalles, and Hal Woodeshick) to suit up for both the original and replacement editions of the 20th-century American League club residing in the nation’s capital. By the time Ramos had pitched his final big-league inning (on April 25, 1970, three days shy of his 35th birthday), the overall ledger stood at 160 defeats balanced by 117 games won.

If Ramos faded from the big-league scene after 1966 (the last season in which he logged at least 50 appearances), he remained active at the end of the decade at both the Triple-A and Double-A levels in a variety of lesser leagues. In 1967 there was a short stint with the Vancouver club of the Pacific Coast League (0-1 in only two outings). A year later there was another larger cup of coffee with Pittsburgh’s American Association farm team in Columbus (1-1, 29 games); in 1969 there was a return trip to Columbus (International League) and also Cincinnati’s farm in Indianapolis (American Association). In 1971 the fading Cuban split time with clubs in Savannah (Double-A Southern League) — where he posted three victories and lost five — and Richmond (Triple-A International League). And in a final 1972 North American professional assignment he visited Tidewater in the International League for nine appearances as part of a futile effort to resurrect a big-league career with the New York Mets. The quick-starter who was in the majors before he was 20 was all washed up as an active player (at least in the United States) before he was 37.

There were also a handful of late-career stopovers south of the border down Mexico way. The bulk of Ramos’s summers in the first half of the 1970s were spent in the Triple-A-equivalent Mexican League, where he eventually logged a respectable 50-38 lifetime ledger. He was 12-6 with Jalisco in 1970 and 13-10 with Puebla in 1972, then moved on to the Mexico City Reds where he also won in double figures two years running. During a final Mexican League sojourn in 1975, he co-managed (alongside fellow Cuban big leaguer Panchón “Pancho” Herrera) the basement-dwelling Villahermosa (Tabasco) Cardinals.

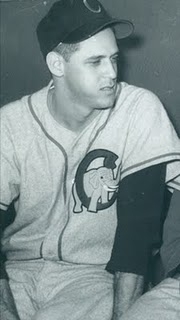

Although perhaps the island’s top prospect, the promising Pinar teenager had never pitched with pro clubs in his homeland before launching his salaried career in the United States. But once he reached big-league stature he immediately returned to make a significant mark in the home-nation four-team Cuban winter circuit. Teaming with Washington sidekick Pascual, Ramos hurled seven seasons (1954-1961) for the Cienfuegos Elephants; he eventually amassed the league’s ninth-best career winning percentage (.595) and also tied a record for most seasons (four) winning 10 or more games.3 He was both rookie of the year (1955-56) and MVP (1960-61) in the league and for three straight years (1958-1961) paced the circuit in innings pitched. He also was a league leader in games won (13 in 1956 and 16 in 1961), complete games (17 in 1961), strikeouts (twice), and shutouts (his final season with three). But in 1958-59 he also rang up the top number for defeats with his 6-13 mark, accounting for nearly a third of his third-place club’s setbacks.

Although perhaps the island’s top prospect, the promising Pinar teenager had never pitched with pro clubs in his homeland before launching his salaried career in the United States. But once he reached big-league stature he immediately returned to make a significant mark in the home-nation four-team Cuban winter circuit. Teaming with Washington sidekick Pascual, Ramos hurled seven seasons (1954-1961) for the Cienfuegos Elephants; he eventually amassed the league’s ninth-best career winning percentage (.595) and also tied a record for most seasons (four) winning 10 or more games.3 He was both rookie of the year (1955-56) and MVP (1960-61) in the league and for three straight years (1958-1961) paced the circuit in innings pitched. He also was a league leader in games won (13 in 1956 and 16 in 1961), complete games (17 in 1961), strikeouts (twice), and shutouts (his final season with three). But in 1958-59 he also rang up the top number for defeats with his 6-13 mark, accounting for nearly a third of his third-place club’s setbacks.

There were also three appearances in the post-winter-league Caribbean Series of the late 1950s (matching champions of the Cuban, Panamanian, Puerto Rican, and Venezuelan winter circuits). In February 1956 the Cienfuegos ace was that tournament’s only undefeated two-game winner. Two winters later he was drafted onto the Marianao roster and again was the pacesetter in starts and victories.4 A single victory in his final tournament appearance with Cienfuegos in 1960 ran the winter championship series ledger to an impressive 5-1 overall. Yet if Ramos was strong in the Cuban winter league he might have been better. Roberto González Echevarría (The Pride of Havana, page 324) quotes sportswriter Fausto Miranda (brother of big leaguer Willy Miranda) as reporting that the handsome, carousing Ramos’s many escapades with women likely had a somewhat negative effect on his overall performance.

Life was not especially kind to Ramos during his rough-and-tumble post-baseball life. He scouted briefly in Latin America before opening a cigar business in his adopted home city of Miami. But any dreams of coaching at the big-league level or perhaps developing young pitching talent in his adopted South Florida home were soon sabotaged by a string of disaster-fraught personal decisions. The retired athlete simply couldn’t adjust to life out of the limelight and would eventually run afoul of the law on serious drug and weapons charges, finally spending three torturous years in a federal prison in Florida. The colorful gunslinger image, once translated into a real-world lifestyle, eventually proved to have its huge and unappealing downside.

In his revealing portrait of Ramos’s tainted immediate post-baseball life, author Edward Kiersh suggested that the handsome Cuban’s wild off-field lifestyle was largely a reflection of a flamboyant, no-holds-barred on-field career. In Kiersch’s view the miscalculations on the mound that led to yielding so many home-run balls only paralleled the bad judgments linking Ramos to a far rougher ride in the multibillion-dollar Miami drug scene of the late 1970s and early ’80s. The ballplayer who once dressed up as a gunslinger for promotional photos eventually found himself immersed in a world of real bullets, immense (even deadly) risks, and true outlaw lifestyles. It was no longer play-acting, no longer merely a game. Getting hammered by the Yankees’ murderous lineup was a far cry from real bullets and play-for-keeps drug wars.

The first serious brush with the law came when the ex-ballplayer was arrested on September 3, 1978, in a Miami bar for harboring a gun (presumably an old habit from his Washington and Cleveland days) as well as a small package of marijuana. Ramos had by that time already invested in his first small cigar-manufacturing outfit in Little Havana and this legitimate business connection temporarily served him well. He was released on condition that he seek counseling, and all charges for this first offense were eventually dropped. Yet the downward spiral continued and less than a year later (July 31, 1979) the “big bust” followed when the athlete-turned-drug-dealer was apprehended (after an anonymous tip to police) while making a large cocaine delivery in South Miami. More evidence was uncovered (several additional kilos of coke stashed in Ramos’s house) and the case moved slowly through the courts for more than two years. But once again Ramos dodged a literal bullet when a judge ruled the search of his house had been illegal.

A third strike came in August of 1980 when Ramos was again arrested, this time for threatening a neighborhood bar owner with a revolver. Now the consequences were more serious — a felony charge of aggravated assault and an 18-month period of probation — but they were perhaps still not serious enough to halt the deadly spiral into big-time crime. The final shoe dropped a year later with a fourth arrest and a series of even more serious charges (speeding, drunken driving, and carrying a concealed weapon). Unfortunately for the pretend cowboy, this was 1980s urban Miami and not 1880s frontier Dodge City. Finally there was a conviction resulting in hard time — a sentence of three years in a Miami penitentiary. But again Ramos may have gotten off easy in light of his one-time baseball fame. Given the nature of his crime and stature as a repeat offender he might well have received a sentence ten times as long.

When Kiersh interviewed Ramos at the Hendry Correctional Institution at the edge of the Florida Everglades for his book chapter back in 1982, he found a man full of excuses, feeding on denial, and displaying little if anything in the way of responsibility or remorse. Like another fallen mound star of the 1960s who turned to a post-career life of crime — Denny McLain — Pete Ramos apparently always lived only by his own rules.5 Regarding the final sentencing for parole violation, the former big-leaguer saw only a case of purposeful entrapment and unjust treatment (perhaps the result of someone’s jealousy of his many liaisons with female companions). He excused the firearm as actually belonging to his wife and left in the car by mistake. He escaped into memories of once meeting Fidel Castro in Havana and hobnobbing with Richard Nixon in Washington. He boasted about how far he had come from the days when he labored as a waterboy in his father’s tobacco fields. His only joys outside of his fading memories were his assignment as pitcher for the facility’s softball team and the battered Yankees cap that prison officials allowed him to keep once the NY logo was torn off (since guards thought it might be too divisive a symbol on the prison grounds).

The ex-con kept his private life largely a well-guarded secret after his 1984 prison release. Precious little is known about family life, spouses, or regular travels between Miami and Managua across the subsequent three decades. Sparse contacts with other exiled Cuban players in Miami and few public appearances at their reunions have been the rule. Ramos did show up for occasional recreational baseball and softball games, and as late as 1988 (in his mid-50s) he pitched briefly in Miami’s Nica League (sponsored by Nicaraguan exiles during that country’s most recent civil war), performing for a team called the Tigres de Hialeah that also boasted José Canseco’s twin brother, Ozzie Canseco. And he briefly served as part-time pitching coach at Miami-Dade Community college in the early ’90s.6 Reports of many liaisons with numerous women have circulated, but only one verifiable marriage and one known offspring are documented. While pitching for the Cleveland Indians and still in his mid-20s Ramos married Zedia Balbuena, a Cuban beauty recently named Miss Cuban Carnival of 1961.7 That marriage produced one daughter (name unverified), reputed to have inherited all of her mother’s stunning beauty. It was obviously the ill-fated marriage to Balbuena that Cleveland teammate Sonny Siebert had in mind in his colorful account of the television shooting incident that caused a rapid divorce.

Ramos’s connection with Nicaragua extends all the way back to his playing days. He appeared there in the short-lived professional winter league of the late 1960s and was once on the losing end of a no-hit effort by local mound hero Tacho Velázquez. He also appeared from time to time in other exhibitions, most notably an undefeated seven-game barnstorming tour in 1967-68 against local pros (shortly after the demise of the Nicaraguan winter circuit), when he and fellow Cuban hurler José Ramón López doubled as outfielders on nonpitching days. And into the early 1980s he occasionally performed in his familiar role on the pitcher’s mound during informal Managua softball games.

But Ramos’s part-time residence in the Central American nation has been largely devoted in recent decades to his start-up cigar enterprise. He began in the 1980s producing a brand of Honduran cigars in a small factory at Esteli (Nicaragua’s third largest city) of which he was part owner and on-duty quality-control supervisor. The marketing of these cigars under the label of the Don Pedro Ramos brand drew upon his baseball fame but the business has been at best only a moderate success. As several online cigar magazines have observed, Ramos had about as much luck in crafting and peddling cigars as he had in winning games back in Washington and Minnesota. A main point of distribution for the product has been a tobacco shop maintained in Miami’s Little Havana district for the past quarter-century.8

But if Ramos had become a legitimate businessman by the 1990s, the rough gunslinger image had apparently not been entirely expunged. One correspondent for the online journal Smoke Magazine (www.smokemag.com) writes in less than glowing terms of his visit with the ex-player while touring Nicaraguan factories in the late ’90s. The anonymous writer explains that Ramos was still packing a pistol on his hip as he had during playing days in Washington and gangster adventures in Miami. The facility was largely empty on the day of the visit but “Of course, Ramos spent a good portion of our visit waving around the pistol he wears on his hip and telling stories about the people he has shot on a dare.” The writer concludes that he didn’t hang around long for the boasting session and the online magazine even provided a photo (Ramos with cigar in mouth, box of Don Pedros in hand, and pistol and holster on hip) as evidence of the strange encounter.

Like many of the more colorful big leaguers of a half-century back, Washington’s “big loser” of the Golden Age ’50s is today the subject of many a tall tale. Those tales may be mostly apocryphal but they make much better reading today than the dry lists of homers gifted or league-leading totals for games lost or innings pitched. Baseball myth always outshines its omnipresent statistical or factual archives.

Mickey Mantle, for one, reportedly commented on Ramos’s penchant for carrying a pistol to the ballpark. The Mick once apparently reflected nostalgically on the delights of playing in the nation’s capital city and said the attraction came in large part because of the pair of colorful Cuban hurlers he used to feed off there: “Pedro Ramos always carried a gun” remembered the Yankee Hall of Famer, “and he and Camilo Pascual would laugh and rag each other about who gave up the longest home runs to me. …”9

A more popular and widely circulated anecdote is one concerning Ted Williams that for years has enjoyed high currency despite the lack of authenticity. The legend has a young Ramos striking out the Splendid Splinter and then rolling the ball into the Washington dugout for safekeeping. At game’s end the Senators rookie approached the Boston dugout hoping for a signature to memorialize his feat. Boston hurler Mel Parnell once related a version of the tale that first had the impetuous Williams exploding in anger, then softening and saying, “All right, give me the goddamn ball and I’ll sign it.” The punch line continues with Williams smacking a towering homer off Ramos a couple of weeks later. Rounding first Williams supposedly shouted at the young Cuban, “I’ll sign that son of a bitch too if you can ever find it!” Unfortunately this same story has been even more frequently attached to the career of another ’50s-era Washington Cubano named Conrado Marrero. Marrero for his part denies it ever happened in his case, and the story (never verified by either of the principals involved) seems far too good to be true, regardless of whose biography it is plugged into.10

But in the end these charming tales never obscure the realities, which teeter somewhere between the brightest and ugliest sides of the fabled American Dream. As an untutored Cuban farmboy, Pedro Ramos rode his talented arm and brazen nature to fame and a substantial career as a popular baseball pitching idol in one of the sport’s true “golden” ages. But there was always more failure than success, more defeat than victory. He pitched with truly anemic teams most of his career and is thus remembered as a record-setting loser; his most memorable niche was the delivery of “gopher balls” to enemy hitters. After baseball he disgraced himself, his countrymen, and his sport with a chosen life of violent crime. And in Miami’s Little Havana Cuban exile community, where a handful of remaining Cuban pro ballplayers of the pre-Castro era are still adored as living idols, Pete Ramos is the one Cuban big leaguer of his generation who remains largely a forgotten man.11

Last revised: August 31, 2011

Acknowledgments

The author is especially indebted to the assistance offered by SABR member and noted Latin American baseball historian Alberto “Tito” Rondon in providing personal anecdotes and sparse details concerning Ramos’s post-baseball activities. Valuable background information was also forthcoming from Cuban scholar and Pinar del Río resident Juan Martínez de Osaba y Goenaga, author of Spanish-language biographies of Pedro Luiz Lazo and Omar Linares.

Sources

Personal Correspondence

Multiple e-mail exchanges with Alberto “Tito” Rondon, Juan Martínez de Osaba y Goenaga (in Cuba), and Ralph Maya (all during August 2011).

Articles

Addie, Bob. “The Senators’ Pistola Pedro.” Baseball Digest, March 1960: 65-66.

Bjarkman, Peter C. “Bridge to Cuba’s Baseball Past.” New York Times, August 14, 2011: Sports Section, 9.

Bjarkman, Peter C. A History of Cuban Baseball, 1864-2006. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Publishers, 2007.

Bjarkman, Peter C. Baseball with a Latin Beat: A History of the Latin American Game. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Publishers, 1994.

Figueredo, Jorge S. Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball, 1878-1961. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Publishers, 2003.

Gonzalez, Raymond. “Pitchers Giving Up Home Runs.” Baseball Research Journal, Volume 10. Cooperstown, New York: Society for American Baseball Research, 1981: 18-28.

González Echevarría, Roberto. The Pride of Havana: A History of Cuban Baseball. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Kiersh, Edward. Where Have You Gone, Vince DiMaggio? New York: Bantam Books, 1983. (“Pedro Ramos, Behind Bars with the Cocaine Cowboy,” 213-220)

Shannon, Mike. Tales From the Ballpark: More of the Greatest True Baseball Stories Ever Told. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2000.

Simons, Herbert. “How to Marry a Ballplayer.” Baseball Digest, September 1964: 17-28.

Torres, Angel. La Leyenda del Béisbol Cubano, 1878-1997. Miami: Review Printers, 1996. (Pedro Ramos Guerra profile on pages 186-187)

Torres, Angel. Tres Siglos de Béisbol Cubano, 1878-2006. Miami: Best Litho, Inc., 2005.

Online

Bjarkman, Peter C. Connie Marrero, SABR BioProject (Published March 2010, updated April 2011).

Bjarkman, Peter C. Adolfo Luque, SABR BioProject (Published April 2010).

“Honduran tobacco is about to reveal its secrets.” Smoke Magazine, September 1998 online issue. http://www.smokemag.com/0998/feature2.htm (pages 2-4).

Pedro Ramos minor league pitching statistics, from Baseball-Reference.com.

“The Ted Williams and Pedro Ramos Story.” Baseball-Fever.com, January 2011 online posting. http://www.baseball-fever.com/showthread.php?101826.

Welch, Matt. “The Cuban Senators.” ESPN Page 2 Journal. Summer 2002 on line issue. http://espn.go.com/page2/wash/s/2002/0311/1349361.htm

Photo Credits

Topps Company, Author’s Collection

Notes

1 Ramos and Pascual eventually stood second and third on the list of Mickey Mantle’s most frequent career home-run victims. Early Wynn (13 gopher balls) ranks at the top of the list.

2 Journalist Addie (Baseball Digest, March 1960) elaborated on the account of Ramos’s first Washington cowboy duds. As Addie remembered it, catcher Clint Courtney showed up at the team hotel in Kansas City with a newly purchased pair of western boots that so intrigued the Cuban that he demanded to be taken to the same location to purchase his own gear. Addie continued his tale as follows: “We flew back to Washington and had to wait around the airport for our bags. I think the funniest sight I saw was Ramos slumped against a pillar, half-asleep. He was dressed in his cowboy suit, boots and all, but he wore a light topcoat. He looked like a little boy who got tired of being Wyatt Earp or Marshal Dillon and was now surrendering to the sandman.”

3 Ramos received his single significant post-career honor when elected to the Miami-based Cuban Baseball Hall of Fame maintained by the Federation of Cuban Ballplayers in Exile. That selection (alongside former big leaguer Tony Taylor) came in 1981 (preceding the selection of teammate Camilo Pascual by two years), and Cuban winter league records were seemingly most responsible for the honor. But it should be pointed out that the Miami hall of fame would by the late 1980s lose most of its credibility as a legitimate honor once it began installing virtually every remaining living exile player. There were 36 inductees in the combined years of 1984-1986 and then (after the institution went dormant for nearly a decade) another 36 in 1997 alone. This Miami hall is not to be confused with the original Cuban Hall of Fame in Havana that enshrined 68 Cuban immortals between 1939 and 1961 and then disappeared after the 1959 Castro-led revolution. As of 2011 efforts were under way to revive the original Cuban “Cooperstown” in either Havana or Matanzas.

4 As is still the practice in the modern-era version of the Caribbean Series, pennant-winning teams representing each of the four winter circuits could draft additional players from within their own league. In this instance, Pedro Ramos was drafted (along with New York Giants backup receiver Ray Noble, another regular for Cienfuegos) to fill out (strengthen) the Marianao Tigers lineup for the post-season series. Big leaguers Minnie Miñoso and José Valdivielso also played on the same championship Marianao ballclub managed by Nap Reyes, and Chicago’s Bob Shaw was the pitching ace.

5 Denny McLain the embezzler (and investor in illegal gaming operations) had nothing on Pete Ramos, the gun toter and drug dealer. Comparing the white-collar crimes of McLain to the drug trafficking, gun possessions, and threatened assaults committed by Ramos provides as stark a contrast as do their big-league winning percentages. If McLain’s reckless lifestyle caused him to unwisely mix with bad company, Ramos’s plunge into a life of hard crime made the Cuban bad company himself.

6 A New York Times article (July 13, 1991) reporting on the defection of future big leaguer René Arocha (during a Cuban national team visit to Tennessee) carried a brief quote from Ramos (“He has the potential of Nolan Ryan”) and cited his coaching assignment at Miami-Dade.

7 The Ramos-Balbuena marriage was announced in a Baseball Digest article entitled “How to Marry a Ballplayer.” Author Herbert Simons listed the Ramos nuptials under a section entitled “Become a Model.” In his poignant portrait of Ramos’s prison experience, Edward Kiersh does not indicate which wife Ramos was blaming for owning the weapon hidden in his vehicle. That it was not Balbuena seems evident since Kiersh also comments on the prisoner’s loss of such valued liberties as “having a cigar, or a weekly visit from his new wife.” He had married (and apparently divorced) Balbuena two decades earlier.

8 Fellow Cuban big-league hurler Luis Tiant Jr. also eventually followed Ramos into the cigar-producing business in Nicaragua. The El Tiante Cigars brand was launched — with the former Red Sox star as front man and major investor — in early 2007, in time for the 25th anniversary of Tiant’s big-league swan song season.

9 The image of a pistol-packing, hot-blooded Cuban is also attached to Adolfo Luque, and a number of stories have been circulated (as recounted in my SABR BioProject biography of Luque) about the quickly-angered Cuban threatening American Negro leaguers with a loaded weapon during his late-career managerial tenures in Mexico and Havana. The Mantle comments may or may not be apocryphal, as much in character as they might seem with likely observations by the Yankee slugger. Author Matt Welch is the source of the Mantle quote (on-line for www.ESPNpage2.com in 2002). But Welch claims he is quoting from Mantle’s 1985 book The Mick, a source where this passage never appears. Also, Mantle’s recollections of Cuba and its ballplayers are in their own right somewhat unreliable. In The Mick Mantle says he visited Havana in the winter of 1953 against the unsettling backdrop of Castro’s raging revolution. But Fidel in truth did not launch his campaign in the Sierra Maestra until five years after Mantle’s Havana visit.

10 The versions of this story attached to Marrero’s career — along with Marrero’s denials — are provided in my SABR BioProject biography of Connie Marrero and also my portrait of baseball’s last living centenarian published in the August 14, 2011, edition of the New York Times. Mel Parnell’s version of the Ramos-Williams story comes originally from David Halberstam’s volume Teammates: A Portrait of a Friendship (Hyperion, 2003), the story of Williams, Bobby Doerr, Johnny Pesky and Dom DiMaggio with the 1949 Boston Red Sox. But if (unlike Marrero) Ramos has never denied the account, the statistical details of his early seasons in Washington certainly do it for him. Facing Williams 10 times in 1955 (his rookie season), 14 times in 1956, and 20 times in 1957, Ramos indeed did yield several homers and numerous hits to the Splinter, yet he never struck him out in those earliest campaign. The only combination of a Ramos strikeout followed by a Williams homer transpires during Ted’s final season of 1960 (where if there was a verbal confrontation it certainly didn’t happen when Ramos was a brash young rookie). Nice legend, no factual basis. (The statistical details of the Williams vs. Ramos at-bats are provided in an on-line commentary at www.baseball-fever.com, posted in January 2011.)

11 One of the best examples of how far Pedro Ramos has fallen off the radar screen for the Miami Cuban exile community is found with Angel Torres’s third self-published volume dedicated to memorializing the pre-Castro Cuban baseball experience. In his 200-page 2005 publication Tres Siglos de Béisbol Cubano, author Torres includes portraits, photos, anecdotes, statistics, and obituaries connected to nearly every imaginable baseball figure of Cuban origin or ancestry. Outside of inclusion in a few statistical lists, Ramos never gets a single mention, and it is difficult to believe that this omission is merely accidental.

Full Name

Pedro Ramos Guerra

Born

April 28, 1935 at Pinar del Rio, Pinar del Rio (Cuba)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.