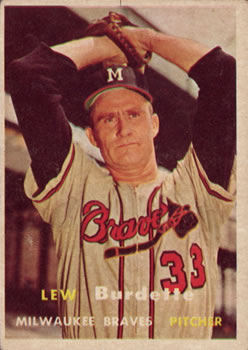

Lew Burdette

Throughout his 18-year major-league career, Lew Burdette was known for his antics as much as for his success on the mound. One of the best control pitchers of the 1950s, the right-hander paired with his roommate and best friend Warren Spahn to form one of the greatest and most durable pitching combinations in baseball history.

Throughout his 18-year major-league career, Lew Burdette was known for his antics as much as for his success on the mound. One of the best control pitchers of the 1950s, the right-hander paired with his roommate and best friend Warren Spahn to form one of the greatest and most durable pitching combinations in baseball history.

Typically in collaboration with Spahn, Burdette was a notorious prankster who did everything from slipping snakes into umpires’ pockets to intentionally posing as a lefty for his 1959 Topps baseball card. On the mound his nervous mannerisms such as fixing his jersey and hat, wiping his forehead, touching his lips, and talking to himself could, in the words of one of his managers, Fred Haney, “make coffee nervous.”1 Burdette’s behavior undoubtedly helped to distract batters, but it also led to frequent accusations that he threw a spitball. While the pitcher, supported by his teammates and umpires, always denied that he threw the spitter, he saw the benefit of cultivating the reputation that he did, as he famously stated, “My best pitch is one I do not throw.” He relied on a sinking fastball, slider, and changeup to reach the 200-win mark on the way to helping to lead his team to two World Series appearances. Above all, though, Burdette is best remembered for turning in one of the most dominant performances in postseason history when his three complete-game victories over the New York Yankees helped lead the Milwaukee Braves to the 1957 World Series title.

Selva Lewis Burdette, Jr. was born on November 22, 1926, in Nitro, West Virginia, to Agnes Burnett and Selva Lewis Burdette, Sr., a plant foreman at an American Viscose Rayon plant in Nitro. Generally known by his middle name, throughout his life he spelled it “Lou.” While he played a lot of sandlot baseball as a child, his first athletic success came with the Nitro High School football team, because the school didn’t have a baseball team. He failed to make the local American Legion team, but after graduating from high school in 1944 he used his father’s connections to get a job at the Viscose plant (his sister and younger brother also worked there) as a message boy on the condition that he pitch for the company’s baseball team. At 17 years old, playing in the Industrial League of the Viscose Athletic Association, Burdette went 12-2 against teams from companies including DuPont, Monsanto, and Carbide.

Burdette’s fledgling baseball career was put on hold when he entered the Air Corps Reserve in April 1945. Because the ranks were full, he was never given the opportunity to fly and instead was placed with a welding outfit. Released from active duty after six months, he enrolled at the University of Richmond and joined the baseball team. Burdette quickly drew the attention of scouts from a number of major-league teams, including one from the Boston Braves who told him, “I don’t like the way you pitch. You may as well forget about baseball.”2 Signed by the Yankees in 1947 for $200 a month, Burdette was assigned to Norfolk, Virginia, in the Class B Piedmont League to begin his professional career.

Burdette pitched in only six games in Norfolk, then was sent to Amsterdam, New York, of the Class C Canadian-American League. In 150 innings he showed a great deal of promise, posting nine wins against ten losses and a stellar 2.82 earned-run average. He continued to improve the following season with Quincy, Illinois, in the Class B Three-I League, finishing the season at 16-11, with an ERA of 2.02 and a league-record 187 strikeouts. He moved up the organizational ladder once again, spending 1948 and 1949 with the Yankees’ Triple-A affiliate in Kansas City, where he roomed with Whitey Ford. Facing tougher competition, for the first time, Burdette struggled, and was relegated to the bullpen.

During his time in the Yankees system, Burdette occasionally worked with roving pitching coach Burleigh Grimes. Though known as one of the great spitball pitchers, Grimes refused to teach Burdette how to throw the spitter out of a concern that if caught Burdette would be banned from professional baseball. However, Grimes suggested that because of his behavior on the mound and the movement on his breaking pitches, particularly his sinking slider, Burdette could use the spitball as a psychological weapon, so that even though he didn’t throw it, batters would convince themselves that he was and come to the plate looking for it.

While with Kansas City, Lew married his fiancée, Mary Ann Shelton. They had met in a bowling alley in Charleston, West Virginia, in October 1948, and decided to get engaged as Lew was leaving for spring training the following March. Upon hearing that the wedding was scheduled for the fall of 1949, the Kansas City front office, wanted to stage the wedding at home plate. Mary nixed the idea and the couple married quietly in Charleston in June 1949. Their first son, Lewis Kent, was born in July 1951.

Despite his pitching struggles in Triple-A, Burdette was called up to the Yankees when the rosters expanded in September 1950. He made his major-league debut for the defending World Series champions on September 26 against the Washington Senators, getting Gil Coan to ground out to end the fifth inning. The next spring he was invited to spring training, then was optioned to San Francisco in the Pacific Coast League. Playing for manager Lefty O’Doul, Burdette started 26 games and did his best to show that he belonged back in the majors, striking out 118 while walking 78 in 210 innings. And although his record stood at 14-12, half of the losses were by one run. Then, on August 29, 1951, Burdette’s career radically changed when he was traded to the Boston Braves as a throw-in when the Yankees sent $50,000 for pitcher Johnny Sain to help them with their push for the postseason.

Burdette spent the final month of the season with the Braves, making three short relief appearances. In 1952 he worked mostly out of the bullpen and demonstrated that he could ably shoulder a heavy workload, leading the team with 45 appearances, foreshadowing the durability that highlighted his career. (During his career Burdette was consistently among the league leaders in innings pitched, games started, and complete games.)

Before the 1953 season, frustrated by his team’s second-tier status in Boston, owner Lou Perini moved the club to Milwaukee. The Braves were immediately embraced by the fans as the players were showered with everything from cars to free dry cleaning. While the Braves had drawn only 281,278 fans in their final year in Boston, they surpassed the mark after only 13 home games in Milwaukee. That first year, they set a National League attendance record, as 1,826,397 saw the Braves play at the new County Stadium.

The Braves’ popularity coincided with their emergence as one of the dominant teams in the National League. Adding Hank Aaron and a number of other key players to the roster, the Braves became perennial pennant contenders, finishing no lower than third in the standings from 1953 to 1960. Beginning the 1953 season in the bullpen, Burdette moved into the starting rotation when Johnny Antonelli and Vern Bickford were injured. Despite making only 13 starts, Burdette finished the season with six complete games, a record of 15-5 and a 3.24 ERA; he was clearly ready to move into the team’s rotation as soon as a spot opened up.

The Brooklyn Dodgers became the Braves’ biggest rivals during this period, finishing one spot ahead of the Braves in the final standings in each of the Braves’ first four years in Milwaukee in races that often went down to the final week. Twice Burdette found himself at the center of run-ins with one of the Dodgers’ African-American stars, and was accused of being racially prejudiced – charges that he and his teammates vehemently denied. In August 1953, the Dodgers’ Roy Campanella charged Burdette on the mound with his bat in hand after he struck out and the two men exchanged angry words. Both benches emptied, but no punches were thrown and play quickly resumed. After the game Jackie Robinson told the press that Campanella only charged the mound after Burdette had addressed him with a racial slur. A similar incident occurred three years later when during pregame warm-ups Jackie Robinson threw a baseball at Burdette’s head (he missed) in response to being called a “watermelon.” Burdette emphatically denied that his comment was racially motivated, claiming that he was joking about Robinson’s “spare tire, not his race.” The two spoke after the game, and Robinson was placated by Burdette’s apology and explanation, and put the matter behind him.

Based on Burdette’s stellar 1953 season as both a starter and reliever, expectations were high for Burdette and the team coming into 1954. Burdette moved into the starting rotation when Antonelli and Bickford were traded. Throughout the season the Braves were plagued by injuries to position players and inconsistent pitching – at the All-Star break, the Braves’ trio of Spahn, Burdette, and Bob Buhl were a combined 15-26 and the Braves sat 15 games out of first place. Burdette had a strong second half, however, going 8-5 to end with a 15-14 record, with an impressive 2.76 ERA, second best in the National League. Despite Burdette’s performance, the Braves were never able to seriously contend for the pennant. In 1955 Burdette finished with a 13-8 record and a 4.03 ERA. But once again, the team was never in contention as the Dodgers simply ran away from the rest of the National League en route to their first World Series title.

During his time in the minor leagues and his first few years in the majors, Burdette returned to Nitro each offseason. Lew and Mary’s second child, Madge Rhea, was born on Christmas Day, 1954. Her birth was particularly newsworthy because Lew helped deliver the baby in a police ambulance on the way to the hospital. Then the growing Burdette family began to split their time between Milwaukee and Sarasota, Florida, where Lew spent his offseasons as a vice president in a local real-estate firm. The couple’s third child, Mary Lou, was born only days before Burdette’s masterful performance in the 1957 World Series. A third daughter, Elaina, was born in May 1960.

As his career was taking off, accusations that Burdette threw a spitball became increasingly common from opposing managers and players. Cincinnati manager Birdie Tebbetts (who became Burdette’s manager on the Braves in 1961 and 1962) and National League President Warren Giles even went as far as separately commissioning motion pictures of Burdette pitching – though the films never showed that he was using the illegal pitch. Braves manager Fred Haney countered that his pitcher was not doing anything wrong, saying, “He’s just a fidgety guy on the mound.” Every time the charges arose, Burdette, along with his teammates and even the umpires, would deny them and emphasize the psychological advantage his nervous actions on the mound provided.

Burdette started on Opening Day in 1956 and cruised to a 6-0 win over the Chicago Cubs, allowing only five hits and one walk. The Braves battled Brooklyn and Cincinnati for the pennant until the final game of the season. With the Braves one game behind the Dodgers on the last day, Haney started Burdette against the St. Louis Cardinals needing a win plus a Pittsburgh win over Brooklyn to take the pennant. While Burdette led his team to a 4-2 victory, the Dodgers also won, and the Braves finished one game back. Although the season ended disappointingly, it was another successful season for Burdette. He led the league in ERA at 2.70 (Spahn finished second at 2.78) and in shutouts with six. His 19 wins, against 10 losses, were the fourth highest in the league, and he received a handful of votes for the Most Valuable Player award.

Expectations were extremely high for the Braves going into the 1957 season. Burdette performed to his now-usual standards, and was named to his first All-Star team. The Braves finally won the pennant, in large part by relying on their top three starters; Spahn, Burdette, and Buhl combined to finish with a record of 56-27. Burdette was 17-9 with a 3.72 ERA.

Spahn lost the World Series opener at Yankee Stadium to Whitey Ford, then Burdette pitched a complete game to defeat Bobby Shantz, 4-2. Taking the mound four days later with the Series knotted at two games apiece, Burdette shut out the powerful Yankees to lead the Braves to a 1-0 victory over his former Kansas City roommate Whitey Ford. When the Yankees won Game Six, it was assumed that Spahn would take the hill for the Braves in the finale. However, with Spahn unable to recover from a bout of Asian flu, Burdette, with only two days of rest, started against Don Larsen. Burdette pitched another complete-game shutout, holding the Yankees to seven hits and allowing only one walk, as the Braves won, 5-0. Posting an ERA of 0.67, Burdette matched the greatest World Series pitching performances by the being the first pitcher since Stan Coveleski in 1920 with three complete-game victories, and the first since Christy Mathewson in 1905 to have two shutouts. As the World Series MVP, Burdette was showered with awards and honors. He gave talks on the lecture circuit, made numerous appearances on television (including “The Steve Allen Show” and Camel cigarette ads), and even cut a novelty record, “Three Strikes and You’re Out.”

Burdette turned in another great season in 1958 as the Braves repeated as National League champions. At 20-10 he reached the 20-win mark for the first time, and tied with Spahn for the best winning percentage in the National League. His batting even improved significantly, as he finished the season with a .242 batting average and 15 runs batted in. On July 10 against the Los Angeles Dodgers at their temporary home in Memorial Coliseum, Burdette smashed two home runs, one a grand slam off Johnny Podres. This was the second time in two seasons that Burdette had hit two home runs in a game – he had done so against Joe Nuxhall in Cincinnati on August 13, 1957.

Facing the Yankees once again in the World Series, after a Spahn victory in the opener, Burdette cruised to a 13-5 victory in Game Two in which he hit a three-run home run in the first inning. But although Milwaukee jumped to a 3-1 Series lead, Burdette lost Games Five and Seven, giving up a combined 10 earned runs and allowing the Yankees to battle back and win the title.

Vying for their third consecutive pennant in 1959, the Braves relied heavily on their core veterans. Eddie Mathews and Hank Aaron responded with stellar offensive seasons and were among four Braves, along with Burdette and Del Crandall, to finish in the top 12 of the MVP voting that season. Although Burdette had a career-high 21 wins, tying him with Spahn for the league lead, and appeared in both 1959 All-Star Games, he lost 15 games and the heavy workload took its toll as he gave up career highs in home runs (38) and hits allowed (312) – both the highest in the league.

Burdette was a central player in one of the most memorable games in history when he took the mound against Harvey Haddix and the Pirates on May 26, 1959, in Milwaukee. Haddix pitched 12 perfect innings, retiring 36 Braves in order, only to lose in the 13th inning when Joe Adcock drove in Felix Mantilla (who had reached on an error). While not as perfect as Haddix had been, Burdette turned in an excellent performance, giving up 12 hits and no runs. After the game a sympathetic Burdette phoned Haddix to tell him, “You deserved to win, but I scattered all my hits, and you bunched your one.” Not sharing Burdette’s sense of humor (or at least his timing), the taciturn Haddix hung up on him.

Tied with the Dodgers at the end of the season, the Braves and Dodgers had a best-of-three playoff for the pennant. Down one game after Carl Willey lost the playoff opener, Burdette took a 5-2 lead into the bottom of the ninth inning of Game Two and seemed well on his way to tying the series. However, after giving up three straight singles to Wally Moon, Duke Snider, and Gil Hodges with no outs, Burdette was pulled and could only watch helplessly as the Dodgers drove in all three to send the game to extra innings. In the 12th inning, facing reliever Bob Rush, the Dodgers’ Carl Furillo drove in Gil Hodges to end the Braves’ season.

After four seasons in which Milwaukee either reached the World Series or came up just short, it was becoming increasingly evident that the Braves dynasty was coming to an end, in large part due to the advancing age of many key players. Burdette performed as consistently as ever, though, going 19-13 with a 3.36 ERA in 275? innings. On August 18, 1960 facing Philadelphia and former teammate Gene Conley, he pitched a no-hitter, defeating the Phillies, 1-0. Allowing no walks, Burdette faced the minimum 27 batters. The only thing that kept him from a perfect game was hitting the Phillies’ Tony Gonzalez with a pitch in the fifth inning. Gonzalez was subsequently erased by a double play.

After dropping to fourth place in 1961 (Burdette was 18-11), the Braves made a concerted effort to bring in younger players in 1962. Birdie Tebbetts, Burdette’s former nemesis from Cincinnati, replaced Chuck Dressen as manager late in the 1961 season. Inconsistent all season long in 1962, Burdette was one of the victims of the youth movement, and started only 19 games, about half his usual number. Then his 13 years with the Braves came ended on June 15, 1963, when he was traded to the St. Louis Cardinals for minor-league pitcher Bob Sadowski and utilityman Gene Oliver.

Although Burdette preferred to start, the Cardinals traded for him because they thought he could be used as both a starter and reliever. His first game with the Cardinals, a complete-game victory over the New York Mets on June 18, seemed to suggest a return to form as a front-line starter. Burdette faced his former roommate Spahn when he faced off against the Braves on July 25. Once again going the distance, Burdette won, 3-1. But he struggled most of the season, posted only a 3-8 mark with the Cardinals, and against his wishes, was increasingly relegated to long relief appearances.

Despite again being on a contending team, Burdette was unhappy with his role on the Cardinals and pushed for a trade. He was traded early the next season to the Cubs for pitcher Glen Hobbie, missing out on the Cardinals’ 1964 World Series title. Reunited with Bob Buhl, Burdette was again given the chance to start. His struggles continued though and he finished the 1964 season with a 10-9 record and an ERA near 5.00. On May 30, 1965, Burdette was sold to the Phillies. Two starts he made in September represented his continuing struggles and inability to pitch for extended stretches. Against Cincinnati on September 5, he gave up six earned runs in 1? innings, and in his next start, the Braves scored five earned runs off him in two innings.

Released by the Phillies at the end of the season, Burdette spent his final two seasons in the majors with the California Angels. Adding a knuckleball, Burdette had an excellent season in 1966 when he made 54 appearances out of the bullpen as a key middle reliever. He won his 200th game on July 22 when he entered a game against the Yankees with the score tied 4-4 and the the Angels scored two runs to win, 6-4. But the resurgence was short-lived and Burdette pitched in only 19 games in 1967. His final major-league pitching appearance came on July 16, when he threw a scoreless eighth inning in a loss to the Minnesota Twins. In August the Angels sent him to their Pacific Coast League affiliate in Seattle, his first trip to the minors since 1951. Burdette appeared in 13 games in Seattle before being recalled in September; however, now 40 years old and recognizing that he was not going to be used in any significant capacity, he retired.

After retiring, Burdette took a job scouting pitchers for the Central Scouting System. In 1969 and 1970 he split time between coaching pitchers in the Gulf Coast League and his hometown of Sarasota, where he tried his hand at various businesses, including a gas station and a night club. In 1972 he became the Atlanta Braves pitching coach, and was reunited with longtime teammate Eddie Mathews when Mathews was named manager halfway through the season. Burdette was excited about rejoining the Braves’ organization, saying, “They’ve always been my club. Everything good happened when I was with the Braves. They’ve been my life.”3 But he left the Braves after the 1973 season, and worked in public relations for a Milwaukee brewery and then in cable television in Florida for 20 years until he retired.

Embracing his connections to the Braves, Burdette was a regular at old-timers games and baseball functions over the years. He appeared on the Baseball Hall of Fame ballot for the first time in 1973, the year that Spahn was elected. Burdette received votes in each of the 15 years he was eligible, peaking in 1984 at 24.1 percent. In 1998 he was inducted to the Florida Sports Hall of Fame and in 2001 was elected to the Braves Hall of Fame.

Burdette died on February 6, 2007, in Winter Garden, Florida, after battling lung cancer. One of the most fitting tributes came from a longtime teammate, shortstop Johnny Logan, who summed up Burdette’s career and personality by remarking, “I don’t know if he threw a spitter or not. His ball would really sink. He was a hell of a battler. Whatever Spahnie did, Lew wanted to do better. They had that competition between them. Lew was a big star but he always gave Spahnie the credit.”4

This biography is included in the book “Drama and Pride in the Gateway City: The 1964 St. Louis Cardinals” (University of Nebraska Press, 2013), edited by John Harry Stahl and Bill Nowlin. It is also included in “Thar’s Joy in Braveland! The 1957 Milwaukee Braves” (SABR, 2014), edited by Gregory H. Wolf.

Sources

Allen, Phil. “Biggest Froggy, Biggest Pond: The Lew Burdette Story.” Baseball Digest, December 1957: 29-33

Buege, Bob. The Milwaukee Braves: A Baseball Eulogy. Milwaukee: Douglas American Sports Publications, 1988.

Chen, Albert. “The Greatest Game Ever Pitched.” Sports Illustrated, June 1, 2009: 63-67.

Driver, David. “The Pride of Nitro: Baseball Star Lew Burdette.” Goldenseal, Fall 1998: 56-62.

Mumau, Thad. An Indian Summer: The 1957 Milwaukee Braves, Champions of Baseball. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2007.

Schoor, Gene. Lew Burdette of the Braves. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1960.

Sutter, L.M. Ball, Bat, and Bitumen: A History of Coalfield Baseball in the Appalachian South. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2009.

Vincent, Fay. We Would Have Played for Nothing: Baseball Stars of the 1950s and 1960s Talk About the Game They Loved. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2008.

Lew Burdette Clipping File at National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, New York.

Notes

1 Phil Allen. “Biggest Froggy, Biggest Pond: The Lew Burdette Story.” Baseball Digest, Vol. 16, no. 10 (December 1957) : 30.

2 David Driver. “The Pride of Nitro: Baseball Star Lew Burdette.” Goldenseal (Fall 1998): 59.

3 “Burdette Sees Life on ‘Outside.’” Unattributed clipping in Burdette’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

4 Tom Haudricourt. “Obituary; Lew Burdette 1927-2007; Farewell to a Hero: Crafty Right-Hander Led Braves to to Glory in ’57 Series.” Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel February 7, 2007: C1.

Full Name

Selva Lewis Burdette

Born

November 22, 1926 at Nitro, WV (USA)

Died

February 6, 2007 at Winter Garden, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.