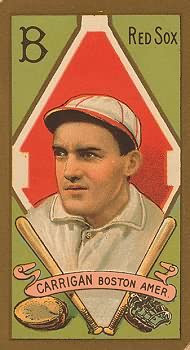

Bill Carrigan

An excellent defensive catcher who provided the Boston Red Sox with above-average offense for his position, Bill “Rough” Carrigan batted .257 in 709 career games, and once finished as high as eighth in the American League in batting average. Behind the plate, the 5-foot-9 175-pounder compensated for his lack of size with sheer toughness. Confrontational by nature, Carrigan rarely backed down from a fight, and usually came out on the better end of his many scraps. From 1913 to 1916, Carrigan was one of the most successful player-managers of the Deadball Era, piloting the Red Sox to back-to-back world championships in 1915 and 1916. After the latter season, the 32-year-old Carrigan, whom Babe Ruth later called the best manager he ever played for, walked away from the game to spend time with family and his business.

An excellent defensive catcher who provided the Boston Red Sox with above-average offense for his position, Bill “Rough” Carrigan batted .257 in 709 career games, and once finished as high as eighth in the American League in batting average. Behind the plate, the 5-foot-9 175-pounder compensated for his lack of size with sheer toughness. Confrontational by nature, Carrigan rarely backed down from a fight, and usually came out on the better end of his many scraps. From 1913 to 1916, Carrigan was one of the most successful player-managers of the Deadball Era, piloting the Red Sox to back-to-back world championships in 1915 and 1916. After the latter season, the 32-year-old Carrigan, whom Babe Ruth later called the best manager he ever played for, walked away from the game to spend time with family and his business.

Most sources indicate that William Francis Carrigan was born in Lewiston, Maine, on October 22, 1883, though the 1900 Census places his birth year at 1884. William was the youngest of three children of John and Annie Carrigan, Irish Catholic immigrants who had arrived in the United States prior to the Civil War. According to census records, John supported the family as a deputy sheriff. During his youth, William worked on local farms when not playing sports, and was a star football and baseball player at Lewiston High. After high school, he moved on to the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts. He starred as a football halfback for the legendary Frank Cavanaugh, who was later the subject of a movie (The Iron Major, starring Pat O’Brien) and is a member of the College Football Hall of Fame. On the diamond Carrigan played for Tommy McCarthy, the baseball star of the 1890s, who converted his young charge from the infield to catcher, a position Carrigan would play the rest of his career.

In the spring of 1906 Carrigan was signed to a Red Sox contract by Charles Taylor, the father of Red Sox owner John I. Taylor. Carrigan joined the struggling Red Sox directly in the middle of the season, immediately catching the likes of Bill Dinneen and Cy Young. In this initial trial, he hit just .211 in 37 games, but impressed with his play behind the dish. Sent to Toronto of the Eastern League the next season, he batted .320, and rejoined the Red Sox in 1908. The right-handed-hitting Carrigan was not a feared batsman, hitting just six lifetime home runs, but was soon one of the more respected members of the team. In 1908 he hit .235 as the primary backup to Lou Criger, but assumed the bulk of the innings for the next six seasons after Criger’s departure to the St. Louis Browns. His .296 average in 1909 was the highest of his career, and the eighth best in the league that season.

The well-mannered Carrigan earned the nickname Rough for the way he played. He was a well-respected handler of pitchers, and had a fair throwing arm, but it was his plate blocking that caused Chicago White Sox manager Nixey Callahan to say, “You might as well try to move a stone wall.” On May 17, 1909 he engaged in a famous brawl with the Tigers’ George Moriarty after a collision at home plate, while their teammates stood and watched. He had a fight with Sam Crawford a couple of years later, and maintained a reputation as someone who would not back down from a confrontation.

Fully entrenched as a regular by 1911, Carrigan had a fine season at the plate (.289 in 72 games) before suffering a broken leg on an awkward slide at second base on September 4. He caught the majority of the innings for the 1912 pennant winners, hitting .263, but was hitless in only seven at bats in the Red Sox’ World Series victory that fall.

In July 1913 the Red Sox were grappling with a series of injuries, fighting among themselves, and limping along in fifth place. Team president Jimmy McAleer fired manager Jake Stahl just months after his World Series triumph, and replaced him with his 29-year-old catcher. Carrigan liked Stahl, as did most of the team, and was reluctant to take charge of a team filled with veterans, many of whom were just as qualified for the job as he. McAleer persuaded Carrigan to take it. The Red Sox were a team fractured along religious lines, as Protestants like Tris Speaker and Joe Wood often crossed swords with the Catholics on the team, including Carrigan and Harry Hooper.

The club’s new manager commanded respect through the unique brand of toughness he brought to the job. Wilbert Robinson, who managed Brooklyn against Carrigan in the 1916 World Series, later said that Carrigan was serious when it came to his pitchers dusting a hitter off: “When Carrigan told one of his pitchers to knock a man down and the batter didn’t hit the dirt, the pitcher was fined.” The team played better the remainder of 1913 before finishing a strong second to Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics in 1914.

The most important event of the 1914 season was the purchase, at Carrigan’s urging, of pitchers Ernie Shore and Babe Ruth from Baltimore of the International League. Although Ruth gave his skipper a lot of credit for his development as a player, Carrigan was humble in his own assessment: “Nobody could have made Ruth the great pitcher and great hitter he was but himself. He made himself with the aid of his God-given talents.” Old Rough did allow that his protégé needed quite a bit of discipline, and Carrigan was there to provide it, even rooming with Ruth for a time. Carrigan caught Ruth in his pitching debut, on July 11.

Some might fault Carrigan for not seeing the potential of Ruth as a hitter. Given that the Red Sox were blessed with the game’s best outfield in Duffy Lewis, Tris Speaker, and Harry Hooper, and that Ruth soon developed into one of the game’s best pitchers, it is understandable why Carrigan did not wish to mess with success. In 1915 Carrigan did use Ruth occasionally as a pinch-hitter, and Babe responded with a team-leading four home runs.

The next two seasons brought Carrigan and his team their back-to-back World Series triumphs. Against the Phillies in 1915, Carrigan famously did not pitch Ruth, which some took as a message to the Babe that the team did not need him to win. Carrigan always disputed this, claiming he wanted to avoid using left-handed pitchers against the heavily right-handed-hitting Philadelphia club.

In early September 1916, Carrigan announced that he would be leaving baseball at the end of the season. He had actually wanted to quit after the 1915 Series, and had so told owner Joe Lannin, but his owner talked him into the one additional campaign. Carrigan later wrote, “I had become fed up on being away from home from February to October. I was in my thirties, was married and had an infant daughter. I wanted to spend more time with my family than baseball would allow.” He retired to his hometown of Lewiston and embarked on careers in real estate (as co-owner of several movie theaters in New England) and banking. A few years later he sold his theaters for a substantial profit and became a wealthy man.

When Lannin sold the club to Harry Frazee before the 1917 season, Frazee drove to Lewiston to try to talk Carrigan into staying on. After that, an offseason did not go by without offers from major-league teams to lure Carrigan back into the game. After a decade of trying, the Red Sox finally summoned Carrigan out of retirement in 1927 to manage the tail-end Sox. Offering proof that the players often make the manager, the Red Sox continued their struggles, finishing last for all three seasons during the second Carrigan regime, despite improving their record each year.

Carrigan was not happy with the way the players had changed in his time away. “These players didn’t talk baseball. They talked golf and stocks and where they were going after the game.” Players resisted practice, individual instruction, or talk of cutoff plays and other strategies. “Inside baseball had become a lost art,” he felt. Interestingly, he thought baseball was too concerned with finding good citizens: “I’ll take players who get arrested every night and win ball games two out of three afternoons to the best behaved second-division gang ever assembled.”

Moving back to Lewiston for good, Carrigan continued a very successful banking career. He joined the city’s Board of Finance in 1938, and became president of Peoples Savings Bank in 1953. Through the years, he was a frequent guest at Fenway Park for ceremonies and reunions. He was named to the Holy Cross Hall of Fame in 1968.

Carrigan married the former Beulah Bartlett in 1915, and they had two daughters, Beulah and Constance, and one son, William Jr. Wife Beulah died in 1958, but Old Rough hung on until July 8, 1969, when he passed away at the age of 85 in his beloved Lewiston. He was buried in Lewiston’s Riverside Cemetery.

Note: This biography originally appeared in David Jones, ed., Deadball Stars of the American League (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, Inc., 2006).

Sources

A primary source for this work was Bill Carrigan’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library. Other sources include:

Will Anderson, Was Baseball Really Invented In Maine? (Bath, ME: Will Anderson, 1992).

Jack Kavanagh, “Quit While You’re Ahead.” The National Pastime 11. SABR, 1993.

Kerry Keene, Raymond Sinibaldi, and David Hickey. The Babe in Red Stockings (Champaign IL: Sagamore, 1997).

Frederick G. Lieb, The Boston Red Sox. (New York: Putnam, 1947).

Tom Meany. Baseball’s Greatest Teams (New York: Barnes, 1949).

Fred Stein. And the Skipper Bats Cleanup (Jefferson NC: McFarland, 2002).

Glenn Stout and Richard A. Johnson. Red Sox Century (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2000).

Paul J. Zingg. Harry Hooper, An American Baseball Life. (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois, 1993).

Full Name

William Francis Carrigan

Born

October 22, 1883 at Lewiston, ME (USA)

Died

July 8, 1969 at Lewiston, ME (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.