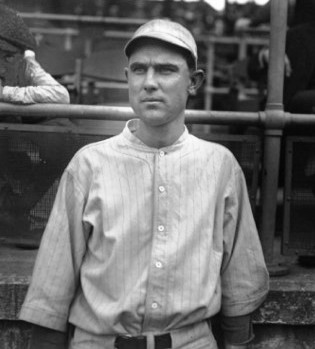

Ernie Shore

A towering Southern farm boy with the mind of an engineer, pitcher Ernie Shore is forever linked with Babe Ruth. Teammates on three clubs and in two World Series, they together tossed what many fans and some historians long considered a perfect game—albeit an odd one in which the Babe faced the first batter and Shore the final twenty-six.

A towering Southern farm boy with the mind of an engineer, pitcher Ernie Shore is forever linked with Babe Ruth. Teammates on three clubs and in two World Series, they together tossed what many fans and some historians long considered a perfect game—albeit an odd one in which the Babe faced the first batter and Shore the final twenty-six.

The second of Henry and Martha Shore’s five sons, Ernest Grady Shore was born on April 24, 1891, in rural Yadkin County, North Carolina. His family raised tobacco, wheat, peas and other crops near the hamlet of East Bend, twenty-three miles northwest of Winston-Salem. Henry’s father also had a farm nearby.

Tall, rangy, and awkward, young Ernie never liked farming. Setting tobacco with a peg, Shore said later, “just kills your back. It wasn’t for me.” As a teenager he occasionally played outfield for a local team called the Red Strings. In 1910 he enrolled in the preparatory department at Guilford College in Greensboro, N. C., the only Quaker college south of Philadelphia. Shore hoped to become a civil engineer. He would teach mathematics at Guilford in the off-seasons after graduating in 1914.

Shore pitched on the college’s baseball squad for five seasons, including two years after he had turned pro—“Guilford being one of the few that allows professionals on its teams (provided the player has made the college team before he enters the professional ranks and makes a certain grade),” Baseball Magazine explained. His coach for four seasons was Chick Doak, later the skipper at North Carolina State. Shore’s college record was 38-8-2.

New York Giants Manager John McGraw, a famous judge of young talent, asked Doak to send Shore North for a trial in 1912. The Giants thus acquired “the thinnest pitcher in captivity,” the New York Times wrote. “He reported yesterday from Guilford College, North Carolina. His front elevation is 6 feet 3 inches, and he looks as if he weighed about 110 pounds.” He actually was just over 6-feet-4 and closer to 180 pounds, but the Times no doubt was correct about Shore’s appearance.

McGraw used the raw right-hander almost exclusively to pitch batting practice. On June 20, however, he dispatched Shore to relieve George Wiltse in the ninth inning of a 21-2 blowout at Boston. The outing went badly. A New York Sun headline labeled the game the “HUB MINSTREL SHOW.”

“Shore got an unmerciful pounding, and on ten hits the Braves scored ten runs,” the New York Tribune reported. “These, however, were not enough to win.” Sporting Life thought the rookie had “about as thrilling a ‘baptism of fire’ as has befallen the lot of any youngster attempting to break into the big show.” Mercifully, only three of the ten runs were earned; the final score was 21-12.

This inning was the only one Shore ever threw for the Giants. McGraw ordered him down to Indianapolis in September. The move looked to Shore “like an attempt to deprive me of all rights to the World Series receipts. I frankly told McGraw that I should not go.” Suspended by his irascible skipper, Shore went home to East Bend, “lost my share of the series money, and felt rather sour at baseball on all accounts.”

Shore paid a $25 fine the following January to gain reinstatement by the National Commission. He played in 1913 at Greensboro in the North Carolina State League, where Chick Doak was his manager. Shore posted a respectable 11-12 record for the tail-end club. Jack Dunn of Baltimore in the International League then drafted him for $400.

Dunn’s 1914 Orioles were considered one of the best minor-league clubs ever assembled. He had “two wonderful pitchers in Ruth and Shore—two more for Connie Mack,” Sporting Life noted. But a new Federal League team in Baltimore siphoned off his fan base, so Dunn quickly sold Shore, pitcher George Herman Ruth, and catcher Ben Egan to the majors. Many expected them to land with Mack’s Athletics, but instead they all went to the Boston Red Sox.

Shore made his Boston debut on July 14 at home against the Indians. It went much better than his inning in the same city against the Braves. Shore was “cool and deliberate in the box, and he showed the Cleveland Club a dazzling assortment of fast balls, curves and change of pace and held them to two hits, winning his game, 2 to 1,” Sporting Life wrote. “It was this game that seemed to wake up the Red Sox to the possibility of World’s Series money.” (Boston finished second to Mack’s strong Philadelphia team.)

The big right-hander won four games in less than a month and stayed with the big club while Ruth went back down to the minors in Providence. The press dubbed Boston’s rookie “Long” Shore. Cleveland manager Joe Birmingham called him “the greatest young pitcher who has broken into the big show since Walter Johnson.” He added, “I believe that Shore’s fast ball is just as fast as was Johnson’s when Walter came east from Idaho. Shore right now possesses a better curve than Johnson.” The Giants’ castoff posted a remarkable 10-5 record in just half a season.

Ruth stayed in the majors with Boston in 1915. He and Shore assembled matching 18-8 records for the season. (Shore had the better E.R.A.—1.64 to the Babe’s 2.44.) Shore had such good movement on his pitches that managers Clark Griffith of Washington and Hugh Jennings of Detroit both accused him of doctoring balls. Shore attributed his remarkable break to the size of his hands and fingers. “Whatever I am able to get on the fast ball in the way of sudden breaks comes wholly from the way in which I hold the ball and deliver it,” he said later.

Shore and his former Baltimore teammates roomed together on the road, but man-child Ruth was a poor match for the mild-mannered Southerner. A story circulated for years that Shore had asked for a new roomie after the Babe had used his toothbrush without asking and then said innocently, “That’s all right, Ernie, I’m not particular.” (Ruth actually used his shaving brush, Shore said, but it made a better story the other way.) The Babe was soon paired with the next in a long succession of roommates. While in Boston, Shore lived in the home of legendary Mayor John Francis “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald. (The mayor’s grandson, John F. Kennedy, was born in 1917 during Shore’s tenure with Boston).

The Red Sox met the Philadelphia Phillies in the 1915 World Series. Ruth didn’t take the mound at all during the series and batted only once as a pinch-hitter. Still the greater Boston star, Shore started Games 1 and 5 for manager Bill Carrigan. “I ate my heart out on the bench in that Series,” the Babe wrote in his 1948 autobiography. Carrigan planned to start him in Game 6, Ruth wrote, but by then the series was over.

Shore faced Grover Cleveland Alexander in the opening game. He pitched well but Alex got all the breaks in a 3-1 Philadelphia victory. “Shore deserved to win,” teammate Tris Speaker said. “He pitched the best game I have ever seen turned in during a world’s series.” The Philadelphia Public Ledger conceded that Alexander “was really outpitched by young Ernie Shore, the giant right hander of the Red Sox.” Even as an elderly man, Shore recalled that if the Phillies’ hits were lined up end-to-end, “they still wouldn’t reach the outfield grass.”

Boston took the next two games, each a 2-1 squeaker. Shore then faced George Chalmers in Game 4. This time the luck was all on his side. “Shore was wild and was batted hard,” the Public Ledger groused. “Sensational fielding and pure luck saved him several times.” Again, the final score was 2-1. The Red Sox wrapped up the series in Game 5 with a 5-4 victory—the fourth consecutive one-run decision.

Shore had another decent season the following year. “ERNIE SHORE HITS HIS STRIDE,” the Globe headlined in May 1916. He finished at 15-10, but Ruth was much better at 23-12. Shore nonetheless was again assigned to Game 1 of the World Series with Brooklyn. Facing Rube Marquard in Boston, he was shaky but leading 6-1 entering the ninth inning. Then walks, bobbles, and screaming singles quickly brought in three Dodger runs.

“When I found they were hitting me, I tried to put more stuff on the ball, and when I did so I couldn’t locate the plate,” Shore wrote in Baseball Magazine. He was lifted for Carl Mays with two outs, which he found “rather tough.” Mays gave up another run to make the score 6-5 before getting the final out. Sportswriter Hugh Fullerton called the game “one of the wildest, weirdest exhibitions of baseball ever staged.”

Shore rebounded to conclude the Series with a 4-1 win over Jeff Pfeffer in Game 5. “The long Carolinian, once passed up by the Giants, came back with bells on and pitched a great world’s series game,” Frederick G. Lieb wrote in the New York Sun. “He subdued the Dodgers with three scattered hits, one of them an infield scratch. He had Brooklyn hypnotized. Its only run drifted in on a passed ball.” Brooklyn outfielder Zach Wheat wrote, “Shore has the best fast ball I ever saw. If we faced him regularly I believe I could fathom it, but in a short series he had us guessing.”

Despite the North Carolinian’s star turn in the series, Ruth continued to eclipse Shore in 1917. “Ernie Shore and Carl Mays are good hurlers but they cannot stand a great deal of work and it looks very much as if it will be up to Ruth and Dutch Leonard to bear the brunt of the pitching responsibility,” columnist Ralph Davis wrote that spring in the Pittsburgh Press. Still, Shore’s greatest moment on a ball field was ahead.

The Babe took the mound at Fenway Park for the first game of a Boston-Washington doubleheader on June 23, 1917. Umpire Brick Owens called the first three pitches to leadoff batter Ray Morgan all balls. After heated jawing, Ruth blew up on Owens’ ball four call and charged with fists flying. Shore loyally maintained decades later that Ruth hadn’t actually struck Owens, but the Bambino admitted in his autobiography, “I really socked him—right on the jaw…They’d put you in jail today for hitting an umpire.” Teammates had to drag the ejected hurler off the diamond.

Player-manager Jack Barry summoned Shore from the bench for an emergency start. “Try to get through this inning,” he said. Shore tossed his five allotted warm-up pitches and began. Morgan tried stealing on the first pitch but Boston catcher Sam Agnew gunned him down. Shore then retired two batters with five more pitches and returned to the dugout. The big right-hander said he felt fine, so Barry sent him to the bullpen to warm up properly while Boston batted.

Shore came back out and retired the next 23 consecutive batters. Then Mike Menosky stepped up to the plate, the last chance for the Senators. The speedy outfielder laid down a bunt ordered by manager Griffith. The bunt was “pretty good,” Shore recalled, but Barry rushed in from second for a bare-hand grab and flip to first for the out. Shore had retired each of the 26 batters he’d faced, plus the man left on base by Ruth.

Years later the former mathematician calculated that he hadn’t thrown 75 pitches the whole game, which he called the easiest he ever pitched. “I just threw it up there,” he said years later, “and they hit it to the outfield or the infield.” (He believed he had pitched better in September 1915 during a crucial 12-inning, 1-0, win at home over Harry Coveleski of the Tigers.)

“Modest Ernie Shore took a place in the Hall of Fame as a no-hit, no-run, no-man-reached-first base pitcher,” the Boston Globe later proclaimed of the Washington game. But whether it constituted a perfect game or simply a unique no-hitter would be debated for decades. The only clarity in 1917 came from William Harridge, secretary of the American League. He wired a sportswriter a month afterward: “Ernie Shore is credited with a no-hit game in the official scores of June 23.”

America was meanwhile fighting World War I in Europe. Enlistments and the military draft began depleting big-league rosters that summer as Shore joined Barry and teammates Chick Shorten, Duffy Lewis, and Mike McNally in enlisting in the Naval Reserves. Shore ended the season at 13-10 with one save as the Red Sox finished second to Chicago. The Sox volunteers then reported for duty in November.

Barry assembled a powerhouse First Naval District ballclub at the Charlestown Navy Yard. Unofficially called the Wild Waves, the team played Harvard, other local colleges, and various military teams. Del Gainer, Herb Pennock and Jim Cooney of the Red Sox signed on, as did Arthur Rico and Henry Schreiber of the Boston Braves. Rabbit Maranville of the Braves also played for a while before shipping out on the battleship USS Pennsylvania. Shore pitched while assigned as a yeoman in the district paymaster’s office.

The North Carolinian took the mound on May 5 as Barry’s Navy nine faced an Army team from Camp Devens skippered by Red Sox teammate Harold Janvrin. The free game before 40,000 fans at Braves Field was “high grade,” declared the Globe, with Shore “pitching in world championship form” in a 5-1 victory. But Barry’s team soon became an embarrassment of riches for the Navy, which began shipping out players. (It eventually would disband the team altogether, citing “exigencies of the service.”) Several teammates left for sea duty, but Shore remained in Boston. He pitched another gem against Camp Devens at Fitchburg, Massachusetts, on June 9, defeating Braves’ prospect Rube Rube Cram 2-1 in ten innings.

Shore was then assigned to officers’ school at Harvard. He received an ensign’s gold stripe in December 1918, becoming the only big-leaguer to earn a Navy commission during the war (although five weeks after the Armistice). “It is his ambition to make a couple of tours of sea duty as an officer before he is placed on the reserve list,” the Globe reported, “and after having done so, the service may appeal to him so that he will stay in it permanently, if he can.”

Ensign Shore was traded to the Yankees the next day, sent to New York with Leonard and Lewis for pitchers Slim Love and Ray Caldwell, catcher Al Walters, and outfielder Frank Gilhooley. This exchange was the “most important baseball trade locally for years,” wrote the New York Times. It also was the first of the blockbuster deals that would dismantle the heart of the Red Sox team and reassemble it in New York.

Whatever Shore’s hopes about going to sea, the Navy didn’t need another newly minted one-striper after the war. He exchanged his dress blues for pinstripes in time for 1919 spring training, but caught an illness from teammate Ping Bodie and was bedridden for a few days. He then endured a miserable 5-8 season in which he often rode the bench or sat in the bullpen. “Ernie Shore came up from the South looking like a million dollars, but he was almost immediately stricken by a bad case of mumps,” the New York Tribune wrote that winter. “He never fully recovered during the season. He should be himself again in 1920.”

The former sailor tried to explain his poor season at spring training in Jacksonville. He rightly noted to the New York Telegram that many other ballplayers returning from the service hadn’t played well in 1919. “The only thing I can attribute it to is that the hard army or navy drilling trained other muscles than those used in ball playing and tightened up some of the baseball muscles. That would apply particularly to pitchers,” Shore said. “I believe my arm is right again and I am hoping I will have one of my old-time Boston seasons.” Many years later, however, he acknowledged, “My arm was shot by that time.”

Shore’s key contribution that 1920 spring came in an exhibition game with the Dodgers when Ruth went into the stands after a heckler who had called him a “piece of cheese.” The man pulled a knife, whose length and lethality varied in the telling. “There was no blood shed,” the Brooklyn Eagle reported. “Pitcher Ernie Shore, of the Yankees, who was close by in his street clothes, stepped between as peacemaker.” (Ruth wrote in his autobiography that Yankees co-owner Til Huston had jumped between him and the fan. Likely, both Shore and Huston had stepped in.)

The 1920 season started encouragingly when 5,000 fans turned out for Ernie Shore Day at a Yankees-Dodgers exhibition in Winston-Salem on the trip North. “They had lots of opportunity for noise-making,” the Eagle reported. “Ernie allowed the Brooklyns no hits in five innings and Ruth wafted the ball twice to the far reaches of the racetrack at the fair grounds.”

Shore’s regular season, though, was even worse than 1919’s. He finished at just 2-2, with one save. The Yankees dispatched him with pitcher Bob McGraw, catcher Truck Hannah, and first baseman Ham Hyatt to the minor-league Vernon Tigers for shortstop Johnny Mitchell in January 1921. (The Vernon club played outside Los Angeles in the Pacific Coast League.)

“The passing of Ernie Shore, the Carolinian collegian, to the minors shows how quickly a man’s usefulness in baseball may wane,” wrote the New York Telegram. “The war hurt many ball players, but none more than Ernie. . . . Some time during that year in the service he lost the smoke on his fast ball, and at one time Ernie ran Walter Johnson a close second for speed. Another crime to be laid at the door of the Kaiser!” Babe Ruth said after World War II that he had thought Shore “was going to be the best pitcher in baseball. He went away to the last war and came back a year later with a dead arm.”

Shore had a 2-5 season in the PCL in 1921, splitting the year between Vernon and San Francisco. The only highlight was tossing a shutout against the Tigers at home with the Seals. His career ended quietly in 1922 with a ruling from Commissioner Kennesaw Mountain Landis that Vernon had to accept him back after San Francisco released him. Shore then asked for and received his release in July, without having pitched an inning for anyone that year.

He hoped to run a ballclub in New England, but instead returned to Winston-Salem to open a car dealership. Shore thus began his life outside baseball. In 1926 he married Lucille Harrelson, a farmer’s daughter from Spartanburg, South Carolina. Five years later he opened an insurance agency after car sales fell during the Depression. In 1936, deeply in debt, Shore was pressed by a group of friends to run for sheriff of Forsyth County. “I don’t mind telling you, I needed the job,” he admitted later. He ran hard, won a runoff election, and remained in office 34 years.

Often wearing a civilian suit with his badge clipped to the belt, Shore had a lasting effect as a lawman. With just six men walking beats when he took office, he brought in the first patrol cars and equipped them with two-way radios—a first for a North Carolina sheriff. By the time he retired in 1970, Shore headed a modern department with 70 deputies.

In 1956, Sheriff Shore helped raise funds to build a new minor-league ballpark in Winston-Salem. (Ernie Shore Field remained in professional use until 2009, when it was replaced by a new facility, sold to Wake Forest University, and renamed.) Sportswriters also called that year for comments on Yankees pitcher Don Larsen’s perfect game in the World Series. “I never saw a cleaner game,” said Shore, who had watched it on TV.

Shore also often met national figures visiting Forsyth County. He was on hand in 1954 to greet Dodger great Jackie Robinson. U.S. Senator Sam Ervin introduced him to President-elect John F. Kennedy in 1960, saying that Shore had once roomed with his grandfather. A deputy recalled that JFK “just hugged the sheriff’s neck.” Baseball scribes called Shore again in 1961 as the Yankees’ Roger Maris’ chased Babe Ruth’s home run record. “He will do it, I think,” Shore said early that September. “I hate to see Babe’s record broken. I guess most of the old-timers do.”

The long debate over Shore’s amazing 1917 relief performance continued. Some record books listed it as a perfect game, others didn’t. “I realize you can make a good case for the game not being perfect, since I didn’t pitch a complete game,” Shore said. “But how complete is complete? You have to get 27 men out. I got 26 of them out and the other was retired when I was pitching. No other pitcher retired a single batter.”

The debate was finally settled in 1991 when an eight-man “committee of statistical accuracy” headed by Commissioner Fay Vincent dropped Shore’s game from the list of perfect games. It instead became a combined no-hitter with Ruth. The committee also took away Harvey Haddix’s no-hitter for his 12 perfect innings for Pittsburgh in a 13-inning loss to Milwaukee, and removed the asterisk from Maris’ home run record (the main issue it was created to address).

Shore wasn’t alive to hear the verdict. The retired sheriff had been in poor health after a stroke in 1975. He died three months following the death of his wife of 54 years, passing away at home in Winston-Salem on September 24, 1980. An old friend in the sheriff’s department remembered Shore not as a ballplayer but as “a law enforcement officer, a leader in our community and a friend to our county.”

For the rest of the baseball community, a line from a 1961 New York Herald Tribune article might have been a fitting tribute to Ernie Shore: “Say his name anywhere that baseball is known about and this one day at Fenway will spring to mind.”

December 31, 2010

Sources

Baltimore Sun

Baseball Digest

Baseball Encyclopedia

Baseball Magazine

Baseball-reference.com

Babe: The Legend Comes to Life, by Robert W. Creamer

The Babe Ruth Story, by Babe Ruth and Bob Considine

Boston Globe

Brooklyn Eagle

History of North Carolina, vol. 3, by Hugh Talmage Lefler

New York Herald Tribune

New York Telegram

New York Times

New York Tribune

New York Sun

The October Heroes: Great World Series Games Remembered by the Men Who Played Them, by Donald Honig

Perfect!: Biographies and Lifetime Statistics of 14 Pitchers of “Perfect” Baseball Games, with Summaries and Boxscores, by Ronald A. Mayer

Philadelphia Public Ledger

Ernie Shore player file, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library

Sporting Life

The Sporting News

Washington Times

Winston-Salem: A History, by Frank Tursi

Winston-Salem Journal

Full Name

Ernest Grady Shore

Born

March 24, 1891 at East Bend, NC (USA)

Died

September 24, 1980 at Winston-Salem, NC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.