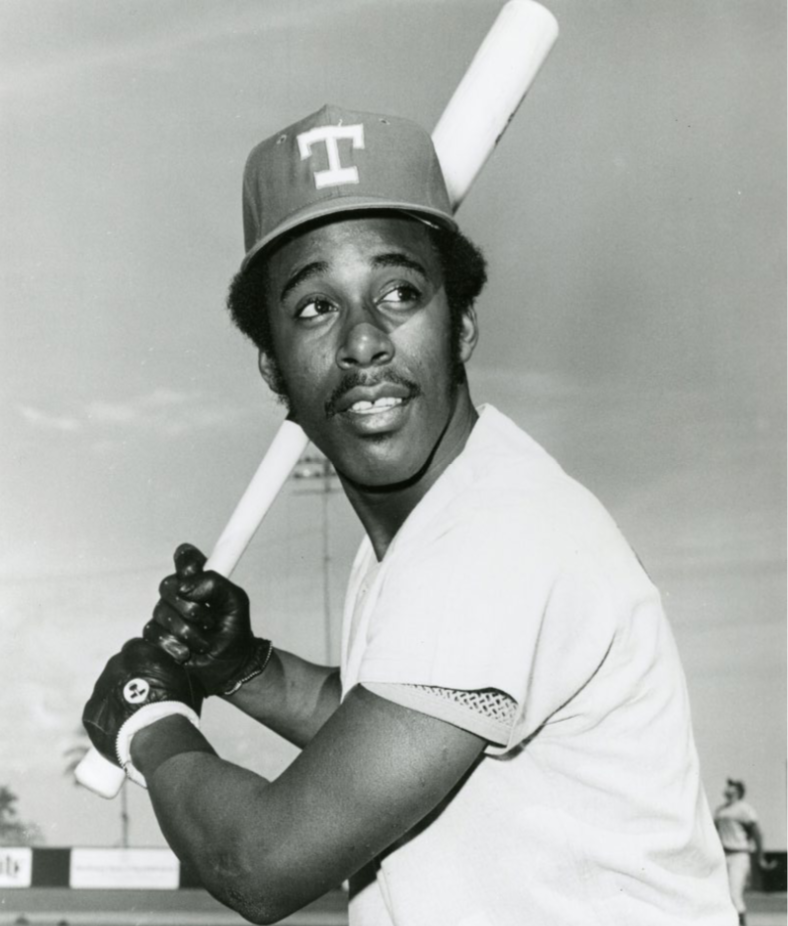

Elliott Maddox

From the moment he was born in the back seat of a car in the parking lot of the East Orange (New Jersey) General Hospital, during a snowstorm on December 21, 1948,1 Elliott Maddox showed a knack for doing things on his terms. He was a premier defensive outfielder who had just begun to show his offensive talent when a cruel date with destiny paid him a visit one rainy night at Shea Stadium. Maddox’s story is not merely one of promise cut short by injury. In an 11-year major-league career, he would have the unusual distinction of being traded from three different teams by manager Billy Martin and playing for four other managers who are in the Baseball Hall of Fame. He was a college-educated man who did not let baseball define or control him. He was also an outspoken figure who had the courage to stand up for what he believed in.

From the moment he was born in the back seat of a car in the parking lot of the East Orange (New Jersey) General Hospital, during a snowstorm on December 21, 1948,1 Elliott Maddox showed a knack for doing things on his terms. He was a premier defensive outfielder who had just begun to show his offensive talent when a cruel date with destiny paid him a visit one rainy night at Shea Stadium. Maddox’s story is not merely one of promise cut short by injury. In an 11-year major-league career, he would have the unusual distinction of being traded from three different teams by manager Billy Martin and playing for four other managers who are in the Baseball Hall of Fame. He was a college-educated man who did not let baseball define or control him. He was also an outspoken figure who had the courage to stand up for what he believed in.

Jackie Robinson had just broken baseball’s color barrier the year before Maddox was born, and even though his parents rooted for the Brooklyn Dodgers and took him to games at Ebbets Field, young Elliott developed a lifelong connection to another team, the New York Yankees, whom he remembered cheering for during the 1958 World Series. Years later he would not only don Yankee pinstripes, but play in the World Series for his favorite team. Still, the only autograph he received or even requested when he was young was that of Jackie Robinson.2

His parents, Willie and Martha,3 both grew up in Georgia and settled in New Jersey after World War II when his father returned from overseas service with the US Coast Guard. His father was an auto mechanic.4 Elliott’s family, which included an older brother, Willie Jr.,5 and a younger sister, lived in Vauxhall, a predominantly African-American section of Union. He played Little League, Teener League, and American Legion ball in Union, New Jersey, and semipro ball for the East Orange Soverels of the Essex League.

During high school, Elliott lettered in baseball, basketball, soccer, and track. By 10th grade he was the starting third baseman for Union High School. In his senior year, as the starting shortstop, he batted cleanup and led his team to the state championship in 1966. That year, he was picked by the Houston Astros in the fourth round of the amateur draft. Following the advice of baseball great and fellow New Jerseyan Larry Doby, he did not sign, instead preparing for college and his future, believing he would be drafted again.6 In contrast, a high-school teammate, pitcher Al Santorini, who signed a contract that same year as a first-round pick of the Atlanta Braves, would be out of baseball at age 24 after amassing only 17 big-league wins.

After receiving scholarship offers from more than 100 colleges, Maddox chose the University of Michigan, based on its reputation both athletically and academically as well as its proximity to relatives in Detroit. Initially a premed major with aspirations of being an orthopedic surgeon, Elliott switched to prelaw when it was evident that he could not play baseball and maintain such a demanding academic schedule.7 While Maddox was the first black student at Michigan on a baseball scholarship, he was actually the third black major leaguer to have played baseball for the university.8 The first two, trailblazing brothers Moses Fleetwood Walker and Welday Walker, played for Toledo of the American Association in 1884 until it became apparent that the league would not tolerate players of color or teams that employed them.

In his sophomore year (1968), his only season playing for Michigan, Maddox led the Big Ten in batting with an average of .467 while playing the outfield. The Detroit Tigers made him their number-one pick in the Secondary Phase of the June 1968 amateur draft, and Maddox was signed by Tigers scout Rabbit Jacobson for $40,000. The Tigers allowed him to report late to spring training to accommodate his academic schedule.

After reporting, Maddox batted .314 in 40 games with Lakeland in the Florida State League before moving to Rocky Mount in the Carolina League, where he hit .297. The memorable highway billboard outside Rocky Mount read: “You Are Entering Klan Country.”9 Unable to rent a motel room there, he found lodging with a local black family. Nevertheless, in 1969 his .301 average was eighth best in the Carolina League. In late 1969, while playing in the Florida Instructional League, Maddox and his four black and Puerto Rican teammates had to sleep in their cars for three days because no motel would give them rooms. The 20-year-old Maddox called Tigers general manager Joe Campbell and, introducing himself as the number-one draft pick, declared, “We’re tired of sleeping in cars; we’re not going to sleep in cars any more.”11 Within two hours they had rooms on the beach like the other ballplayers. Maddox’s outspokenness raised concerns with the Tigers when they learned he had participated in civil-rights sit-ins at the University of Michigan, and the GM “warned me about any future demonstrations.”12

Maddox made the Tigers’ big-league club in 1970 spring training. His major-league debut came as a pinch-hitter on April 7, when he grounded out against the Senators’ Joe Grzenda. Batting against the Indians’ Dean Chance in the fourth inning on April 21, Maddox singled home the tying run with his first major-league hit. He then got an infield hit in the ninth and scored the decisive run. He hit his first big-league homer nine days later off the Royals’ Mike Hedlund in the ninth inning to seal a Tigers win. By June, manager Mayo Smith had Maddox batting second between Dick McAuliffe and Al Kaline.13 He showed his versatility by playing six positions that season. In September, Maddox returned to Michigan for his senior year while simultaneously playing for the Tigers 40 miles away. As he later described it, “I was literally playing and going to college at the same time. I did homework on the road trips and always had my books around the locker room. Some of the guys, like Gates Brown, used to kid me about using big words in the dugout, but everything went pretty smoothly.”14 For the season he had an on-base percentage of .332 despite batting only .248, and was voted the Tigers’ rookie of the year by the Detroit Sports Broadcasters Association.

After the 1970 season, manager Smith was fired and was replaced by Billy Martin, who in his only season of managerial experience, had guided the Minnesota Twins to the American League West title in 1969, during the first year of divisional play. Under Martin, the Tigers immediately traded Maddox along with pitchers Denny McLain and Norm McRae and third baseman Don Wert to the Washington Senators for pitchers Joe Coleman and Jim Hannan and infielders Ed Brinkman and Aurelio Rodriguez. Of the players the Senators received in the deal, only Maddox would still be playing by 1973. Denny McLain, who had been suspended for associating with gamblers, was one year removed from back-to-back Cy Young Awards, including the first 30-win season in 34 years.

This deal paid dividends for the Tigers, who won the American League East title in 1972. The Senators had just been purchased two years earlier by Bob Short, who over-leveraged himself in a deal that saw him outbid comedian Bob Hope for bragging rights to a major-league team in the nation’s capital.15 In order to help attract fans to the lowly Senators, whose ticket prices were the highest in the league,16 Short hired Ted Williams, who had been retired from baseball for nine years and had never managed before.

Maddox was hardly intimidated by the legendary Williams, and was not afraid to challenge his orthodoxy about baseball or politics. “He was lecturing us on hitting one day and I said that’s not the way Clemente and Aaron do it, and that made him mad,” Maddox said. “He couldn’t understand that not everyone is 6-3 and 200 pounds and has his reflexes. And I’d agitate him about Nixon. He thought Nixon was the greatest, and when I said something about him, he’d sputter all over the place.”17

Maddox recalled reporting to the Senators in 1971 during the Vietnam War, thinking he would be drafted. He described showing up in Pompano Beach for spring training with a big Afro and “looking like Jimi Hendrix with the tassels hanging down. And which just irked Ted to no end my coming in dressed like that.”18 When Maddox displayed a “Free Angela Davis” bumper sticker on his locker, referring to the radical activist who was jailed and later acquitted in a high-profile murder case, he was told to remove it, and believed he was from then on labeled a troublemaker, and was threatened with being sent down to the minors.19

One player in spring training who liked the bumper sticker and presumably the courage in displaying it was Curt Flood, himself no stranger to bucking authority.20 That spring, Maddox briefly roomed with Flood, whose own courage to fight baseball’s reserve clause made him a pariah in the baseball establishment and forced him to miss the 1970 season. Flood was signed by Bob Short as a big-name attendance draw after refusing to play for Philadelphia when the Cardinals traded him to the Phillies. Maddox greatly admired the way Flood took a principled stand against the baseball establishment,21 and almost certainly regarded Flood as an inspiration years later when he too would take baseball to court. Maddox said his later experience as a player representative could be attributed to Flood’s example, among other factors.22

Maddox soon proved himself a valuable fixture in center field, as he led all American League outfielders in 1971 with 3.05 Range Factor per Nine Innings. In early 1971, Williams said of Maddox: “He’s going to be some player in two years.”23 At the plate, Maddox hit an anemic .217 for the season. But the disappointment that would be seared into the collective memory of DC baseball fans in 1971, and for decades to come, was when owner Bob Short moved the team to Arlington, Texas, where they became the Texas Rangers. A blog account of the riotous last Senators game at RFK Stadium recalled that after two teenagers’ homemade banner cried, “How Dare You Sell Us SHORT,” several players showed their support. “Outfielder Elliot Maddox gave the Black Power Fist Salute with his batting glove on – to the youngsters – to great admiration from the fans.”24 Maddox hit an eighth-inning sacrifice fly that put the Senators ahead, 7-5, and proved to be the last Senators at-bat, when a runner was caught stealing. In fact, as the Yankees batted in the top of the ninth inning, angry fans, feeling betrayed by the owner’s move to greener pastures, rioted to the extent that the game could not be finished and the Senators lost by forfeit.

With the Rangers, Williams called Maddox “perhaps the best defensive center fielder in the American League.”25 The Rangers experimented with Maddox as a switch-hitter during spring training, though that was soon abandoned when his low average cost him the Opening Day center-field job to rookie Joe Lovitto. Maddox became the regular center fielder in late April. He was batting just .224 on June 12 when a pulled muscle kept him out of the lineup for 17 games. After many games as a pinch-runner or defensive replacement, Maddox started games in left and right before regaining the center-field job on August 4. During a 13-game span in August, Maddox batted .327 and raised his average to a modest .252. His season ended abruptly on August 29 when he broke his hand while diving back to first base at Yankee Stadium.26 Still, in just 98 games, he stole 20 bases, tied for 12th in the American League. The Rangers finished sixth in their division with a record of 54-100.

In 1973 Maddox was optimistic that his injuries and underperformance from the year before were behind him and that he would establish himself not only as the regular center fielder, but as a decent hitter. Ted Williams departed and was replaced by rookie manager Whitey Herzog. In spring training Maddox predicted he would hit .280. Herzog downplayed such expectations, saying, “We’ll take .250 or .260 with all his other assets.”27 Indeed, Maddox started off well and was among the league leaders at the end of April with an average of .326. Then his productivity declined sharply. In May and June of 1973, he missed 20 games with a sore shoulder and pulled hamstring.28 He was batting .228 in September when Herzog was replaced by Billy Martin for the final 23 games of the season. Maddox played in just 11 of those games, starting two, and going 4-for-10, ending the season at .238. For the season he stole only five bases, and none after July 1.

The Rangers sold Maddox to the Yankees for $40,000 in March 1974. It was a welcome opportunity for the New Jersey native to show the team he cheered for as a boy that he was better than his major-league career to that point, and worthy of the first-round draft pick he had been six years earlier.

He also was starting with a clean slate under manager Bill Virdon, who commented, “After we got him, I heard he was a militant. But I don’t pay attention to that stuff.”29 In late May, the Yankees skipper caused a stir by moving veteran Bobby Murcer from center field to right and naming Maddox as the regular center fielder. As Virdon, himself a former outfielder, recalled years later, “Maddox was one of the best while he was physically able.”30 Many believed that Murcer belonged in center, the rightful heir to former teammate, Yankee legend, and fellow Oklahoman Mickey Mantle. Maddox was already hitting .283 at the time of the switch, but afterward both he and Murcer showed increased production and the Yankees won 13 of their next 19 games. The decision to move Murcer from center field to right field in favor of Maddox was even mentioned on Maddox’s 1975 Topps baseball card: “One of Mgr. Virdon’s most controversial moves of 1974 was inserting Elliott in centerfield and moving Bobby Murcer to right. Elliott responded with superb hitting and flawless fielding.”31

In July 1974 Maddox had the satisfaction of two four-hit games two days apart, against teams he had formerly played with, on July 3 in a loss to the Tigers and on July 5 in a 14-2 triumph over Billy Martin’s Rangers. The Yankees battled for the division lead all year, and held first place into the latter half of September, but ultimately finished second, two games back of the Baltimore Orioles. For Elliott Maddox, 1974 would go down as his career year as he finally stayed healthy and showed he could hit as well as field. His .303 average was fifth best in the American League, and his .395 on-base percentage ranked fourth. Despite only three homers and 45 RBIs, he ranked fourth in Wins Above Replacement (WAR) among position players with 5.4. He was second among league outfielders with 18 assists. He finished eighth in the American League MVP voting. The New Jersey Sportswriters Association named him Player of the Year.32

While Elliott Maddox the ballplayer was finally realizing his potential through consistency on the field, Elliott Maddox the man decided to convert to Judaism so that his religious affiliation would be consistent with his personal beliefs. The son of a Baptist father and Methodist mother, Maddox was first exposed to Judaism through several childhood friendships and visits to the home of his Little League coach, Mr. Shapiro, whose family warmly welcomed him. He believed that the upbringing of Jews and blacks alike made them “more willing to accept people for who they are.”33 His sense of spiritual kinship between Jews and blacks was solidified during a Judaic history class at the University of Michigan. “Talk about slavery, the Exodus … coming out of Africa, you may want to call it Egypt.”34 His parents were supportive of his newfound spiritual identity: “They thought it was great that I finally believed in something.”35 In a 2004 article that coincided with his upcoming appearance at a Baseball Hall of Fame event honoring Jews in baseball, Maddox addressed “anti-Semitism on the field, in the clubhouse, from management. It’s alive and well in a very sick way.”36 In a 2010 documentary on Jews in baseball, Maddox quipped, “I always considered myself a good two-strike hitter. Being black and a Jew I got the two strikes. So, now I can handle anything.”37

While playing in New York, Maddox upheld his reputation for being outspoken in addressing the racial divides even on integrated teams. He said that when a black football player was mobbed by teammates following a touchdown, “half those guys would probably stab him in the back if they had the chance. The only reason they’re patting him on the back is that he’s putting money in their pockets.”38

During spring training, when Maddox accused Billy Martin of lying to him about his chance to play when he was with the Rangers, he became the target of a couple of errant pitches, and a brawl ensued.39 The feud continued into the regular season when the Yankees and Rangers first played in New York. When Maddox was predictably plunked by a Rangers pitcher in May, he asked Commissioner Bowie Kuhn to intervene “before somebody gets seriously hurt.”40 That would be the last time he would play against Martin’s Rangers, though he would still have to deal with Martin again.

During the 1974 and ’75 seasons, while Yankee Stadium was closed for renovation, the Yankees played all their home games at Shea Stadium, the Mets’ ballpark in Flushing, Queens. Playing on a soggy Shea Stadium outfield on Friday night, June 13, 1975, with the Yankees clinging to a narrow lead in the ninth inning, Maddox slipped while catching a fly ball and suffered a season-ending injury. He tore cartilage and two ligaments in his right knee. Still, the Yankees, who were battling for first place and desperately needed outfielders following injuries to Bobby Bonds, Lou Piniella, and Roy White, wanted Maddox to return that season and put off surgery until after the season. The day after his injury, the team fell out of first place and only briefly returned. In August, less than three months later, the Yankees fired Bill Virdon and replaced him with Billy Martin, who at least publicly said all the right things about wanting a healthy Maddox back in the lineup.41 On September 3, with the team already 12½ games out, surgery was finally performed when it was obvious how serious the injury was. That season, which had started out with such promise, ended with Maddox batting .307 in just 55 games. The Yankees finished in third place, 12 games behind the Red Sox.

Maddox, wearing a heavy metal leg brace, received a standing ovation from appreciative fans in his first home game at Yankee Stadium on June 22, 1976, over a year after his devastating injury, when he was announced as a pinch-hitter, before responding with a double. Not performing as well as hoped, he returned to the disabled list on July 1. He was returned to the active roster by September 1 in order to be eligible for the postseason. He hit just .217 in 18 regular-season games in 1976. In three ALCS games against the Kansas City Royals, he was 2-for-9 with a double and an RBI. As the starting right fielder in Game One of the World Series, Maddox hit a triple in his second at-bat. The World Series that year was the first one to employ the designated hitter, a role that Maddox filled in Game Two. (He was 0-for-3.) Although the Yankees were swept in four games by the Cincinnati Reds, nobody on the team was happier and had worked harder to be there than Elliott Maddox.

Maddox wound up suing the Yankees, the Mets, the City of New York and others for $12 million in damages for the unsafe playing conditions he had to play under at Shea Stadium that fateful night that changed everything. Though he had alerted the manager and grounds crew to the wet field conditions before the incident, that fact was used to argue that he assumed the risk because he could have refused to play.42 That legalistic argument may be unrealistic in the context of a player who does not want to hurt his team’s chances during a pennant race, or jeopardize his job security, or compromise his teammates’ trust by refusing to play in unsafe conditions. In 1985 the New York State Supreme Court ruled against Maddox.43

In November 1976, Maddox had a second surgery to remove seven chips in his knee, without the consent of Yankees doctors. In January, the Yankees traded him along with outfielder Rick Bladt to the Orioles for Gold Glove outfielder Paul Blair. Maddox said that upon learning of the trade, he jokingly told Orioles manager Earl Weaver to sell his house. “It stood to reason that as soon as I got there, Billy Martin would be on his way to Baltimore.”44 From his debut in July until the end of the season, Maddox batted .262 in 49 games for the Orioles.

Maddox was not away from New York long. He signed a five-year $950,000 free-agent contract in November 1977 with the National League Mets. There were a few noteworthy aspects of his signing, one of which was that he would be returning to Shea Stadium, the site of his devastating injury. Even though the Mets were a party to his lawsuit, as leaseholders of Shea Stadium, it did not stop them from signing him. Also, Maddox was among the first major-league free agents ever signed by the Mets, who had been known for their parsimonious refusal to pay Tom Seaver and other stars their fair market value. Maddox played with the Mets from 1978 through 1980, under manager Joe Torre, posting averages of .257, .268, and .246 respectively. He endured a couple more stints on the disabled list during that time. In 1980 he played in 130 games, mostly at third base, which he found harder on his knees than playing the outfield. Despite his discomfort at the hot corner, his .956 fielding percentage was fourth among league third basemen. In 1980 he was hit by pitch a league-leading six times. In February 1981, the Mets released Maddox with two years remaining on his contract. For his career, he hit .262 with 18 homers and 234 RBIs over 11 seasons.

After retiring from baseball, Maddox worked as an investment banker on Wall Street for seven years and managed an ice-cream parlor that went bankrupt.45 He coached for the Yankees in Fort Lauderdale and as a roving instructor in 1990-1991. He then worked for eight years as a senior foster-care counselor in Broward County, Florida. As a single father, he had to stop when it interfered with his family time. Maddox had three children with two wives.

In 1989, as the Soviet Union began to unravel, Maddox traveled to Poland to help establish Little League baseball.

In 1997 he was inducted into the Union County, New Jersey, Baseball Hall of Fame. In 2004, the Jewish Sports Hall of Fame inducted him and his former Yankee teammate Ron Blomberg as honorees. In 2003, a circuit judge in Florida acquitted Maddox of grand theft and perjury charges in connection with income received while on disability leave from his counselor position with state Department of Children and Families.46 In 2006, he taught baseball fundamentals to Israeli youths in preparation for the short-lived Israel Baseball League.

In 2010, 35 years after his conversion to Judaism, Maddox had a bar mitzvah ceremony attended by more than 300 youngsters at the Ron Blomberg Baseball Camp in Milford, Pennsylvania, where Maddox had run clinics for five years.47 Over the years, he has had no fewer than 13 surgeries on his knee.48 As of 2018, Maddox lived in Coral Springs, Florida.

This article was published in “The Team That Couldn’t Hit: The 1972 Texas Rangers” (SABR, 2019), edited by Steve West and Bill Nowlin.

Notes

1 Transcript of Elliott Maddox interview by Rebecca Alpert, for Jewish Major Leaguers, Inc., conducted March 7, 2005. The 26-page oral history can be found in Maddox’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library. All existing baseball databases show Maddox as being born on that date in 1947.

2 Ibid.

3 Dave Hirshey, “Elliott Maddox: ‘I Always Say What’s on My Mind,’” New York Times Magazine, April 23, 1978.

4 Peg Stomierowski, “Bias Plagues Sports Like Other Fields, Says Maddox,” Binghamton Press, February 13, 1975.

5 njsportsheroes.com/elliottmaddoxbb.html, retrieved March 5, 2015.

6 Elliott Maddox, “Blending Athletics and Academics,” New York Times, June 15, 1980.

7 Peter Ephross with Martin Abramowitz. Jewish Major Leaguers in Their Own Words (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co, Inc., 2012), 170-71.

8 baseball-almanac.com/college/university_of_michigan_baseball_players.shtml.

9 Hirshey.

10 Sam Abady, “Appeal Play – Maddox in Mudville,” baseballlibrary.com, May 28, 2007, retrieved on March 5, 2015. Note: As of early 2018, this site now seems to be in accessible.

11 Ephross, 172-73.

12 Hirshey.

13 Watson Spoelstra, “Maddox Quick to Learn – Tiger Tutors Taking Bows,” The Sporting News, June 27, 1970: 16.

14 Maddox. “Blending Athletics.”

15 nats320.blogspot.com/2006/11/night-my-washington-senators-died_26.html.

16 Ibid.

17 Larry Merchant, “The Yanks’ Main Man,” New York Post, undated September 1974 newspaper clipping in Maddux’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

18 Ephross, 172.

19 Ibid.

20 Brad Snyder, A Well-Paid Slave: Curt Flood’s Fight for Free Agency in Professional Sports (New York: Viking, 2006), 214.

21 Ibid.

22 Interview by Rebecca Alpert.

23 George Minot Jr., “Williams Looks to Knowles for Longer-Lasting Relief: Maddox Tickles Manager’s Fancy,” Washington Post, February 25, 1971 retrieved from ProQuest Historical Newspaper Online Archive.

24 nats320.blogspot.com/2006/11/night-my-washington-senators-died_26.html.

25 Randy Galloway, “Maddox Eyes ’73: Start of Something Big,” The Sporting News, September 23, 1972: 36.

26 Merle Heryford, “ ‘Forgotten Man’ Maddox Producing,” The Sporting News, May 26, 1973: 10.

27 Merle Heryford, The Sporting News, May 26, 1973: 14.

28 Randy Galloway, “Ranger Ramblings,” The Sporting News, June 2, 1973: 4.

29 Merchant.

30 Murray Chass, “To Break a Man’s Heart, Take Center Away,” New York Times, March 1, 2005.

31 75topps.blogspot.com/2010/02/113-elliott-maddox.html.

32 Hirshey.

33 Ephross, 170.

34 Ibid.

35 Ron Kaplan, “A Switch Hitter’s Conversion,” New Jersey Jewish News, August 26, 2004.

36 Ibid.

37 “Jews and Baseball: An American Love Story,” Clear Lake Historical Productions, 2010.

38 “Education Gives Me Free Voice, Ballplayer Says,” Binghamton Press, February 14, 1975.

39 Murray Chass, “Maddox, Martin: No Love Lost,” New York Times, May 24, 1975.

40 Phil Pepe, “Maddox Tired of Ducking, Wants Kuhn to Stop Billy,” New York Daily News, May 25, 1975.

41 Phil Pepe, “Martin Admits Error, Cottons Up to Maddox,” New York Daily News, August 16, 1975.

42 Abady. See also Adam Nagourney, “Ex-Yankee Strikes Out in Lawsuit,” New York Daily News, November 23, 1985.

43 See Abady and Nagourney.

44 Hirshey.

45 “Maddox Pays Up for a Bad Check,” New York Post, June 27, 1989.

46 “Elliott Maddox: Who Knew?,” Blogpost, July 15, 2003 contained article by Paula McMahon, South Florida Sun-Sentinel (Fort Lauderdale), July 15, 2003. Retrieved from forums.nyyfans.com/showthread.php/45792-Elliott-Maddox-who-knew, on March 5, 2015.

47 Nate Bloom, “Interfaith Celebrities” column, August 17, 2010, Retrieved from interfaithfamily.com/arts_and_entertainment/popular_culture/Interfaith_Celebrities_Is_Sedgwick_Closer_to_an_Emmy_or_Will_Margulies_Make_Good.shtml.

48 njsportsheroes.com/elliottmaddoxbb.html.

NOTE 10

This website needs to be fixed.

Also Ibid. On NOTES 44, 45 and 46

Full Name

Elliott Maddox

Born

December 21, 1947 at East Orange, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.