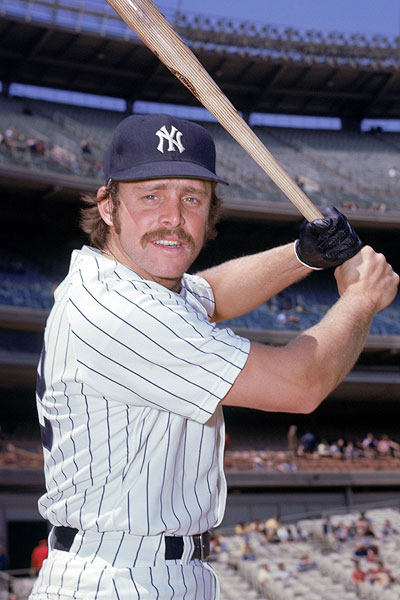

Ron Blomberg

It may have been happenstance that made Ron Blomberg own a piece of history as baseball’s first designated hitter. After he overcame anti-Semitism in his hometown of Atlanta to become the number one overall pick by the New York Yankees in the free agent draft in 1967, his dream of playing in New York City, where there was a large Jewish population, was going to be fulfilled.

It may have been happenstance that made Ron Blomberg own a piece of history as baseball’s first designated hitter. After he overcame anti-Semitism in his hometown of Atlanta to become the number one overall pick by the New York Yankees in the free agent draft in 1967, his dream of playing in New York City, where there was a large Jewish population, was going to be fulfilled.

Unfortunately, his long-range plans were interrupted by constant injuries. Just as Blomberg was coming into his prime, he missed virtually two full seasons. But there is much more to Ron Blomberg than being the first designated hitter. As the saying goes, “Peel an onion and there are lots of layers.” Although his career on the baseball diamond may have come to an abrupt halt, he was still able to be a positive influence as well as enriching others through his works as a motivational speaker and his annual youth baseball camp.

Ronald Mark Blomberg was born on August 23, 1948, in Atlanta, Georgia. He was the second son born to Sol and Goldie Rae (nee Sisselman) Blomberg. The Blombergs operated a jewelry store on Alabama Street in Atlanta. When Ron was 13 years of age, his older brother Alan passed away from an undisclosed illness on April 20, 1961.1 The family met a lot of anti-Semitism in the south. “I grew up hearing anti-Semitic talk a lot,” said Blomberg. “I heard it. I saw it. My parents had always told me you have to have a strong faith, you will always have adversities in life, people will be against the Jews, that I had to watch out for it and had to be a lot stronger. If somebody said something to me along those lines, it made me even stronger. My conviction was strong.”2

Many of Blomberg’s teammates in youth baseball leagues did not know or had never met a Jewish person. But nobody confronted Blomberg because he was often the best player on whatever team he played for. “A synagogue firebombing occurred just three blocks from our house and made national headlines,” said Blomberg, “as depicted in the movie Driving Miss Daisy. There were constant Ku Klux Klan marches, with Klansmen wearing their pointed hats, giving out pamphlets that were anti-Semitic, anti-black and anti-Catholic.”3

Blomberg was a three-sport star at Druid Hills High School in Atlanta. He excelled in basketball and baseball, earning 125 college scholarship offers in basketball. One of those offers came from UCLA, and Blomberg signed a letter of intent to play for coach John Wooden and the Bruins.

The New York Yankees owned the first draft selection in the free agent draft on June 6, 1967. They used that pick to select Blomberg, and as a result he cancelled his plan of attending UCLA. However, he did enroll at DeKalb College in Atlanta to take classes in the off season. The Yankees and Blomberg agreed on a contract reportedly worth $90,000.4 “I feel that Ronnie is the best pro prospect to come along in several years,” said New York general manager Lee MacPhail. “Every club in baseball had him high on their draft list, but since we got first choice, we got him.”5

Signing with the Yankees was a dream come true for Blomberg. “Once I signed with the Yankees, I could not play any type of college sports,” said Blomberg. “So, it was a no-brainer, being a kid who idolized the Yankees and Mickey Mantle, being a Jew coming up from the South, and going to New York City where there are a million Jews. I had an opportunity to fulfill my dream. Luckily, I did, and it was great!”6

Like most young players, Blomberg was leaving home alone for the first time. His first stop on the Yankees’ minor league chain was Johnson City, Tennessee, in the Rookie Appalachian League. A left-handed batter, the 17-year-old was the only player to participate in every game, and led the team in most offensive categories, posting a.297 BA with 10 home runs. . The following season at Kinston of the Class A Carolina League, Blomberg was switched from first base to center field, a position he had never played. Kinston manager Bob Bauer was hoping for a seamless transition. “He’s still green, but he has all the tools,” said Bauer. “Hitting is his best feature and his running is above average. All he has to do is learn how to play center field.”7 Learning a new position at 18, he slipped to .251, but welcomed the change. “I’m glad they switched me to center field. I’ve got a lot to learn, though, especially how to throw overhand from out there. But I am gradually catching on.”8

One story about Blomberg occurred away from the diamond. Known to have a hearty appetite, he was put to the test in a diner outside Kinston. The restaurant offered a deal whereas if the customer ate a 72-ounce steak and all the trimmings within an hour, the meal was free. If not, the bill was $25. Blomberg finished it off within a half hour and asked for seconds. “Ronnie didn’t eat that much,” said his father. “Oh, on the way home from school he might stop in for two or three submarine sandwiches or a half dozen hamburgers, that is all. We had supper quite late, about six, and he needed a snack after school.”9 A snack that would make Fred Flintstone blush.

After batting .284 with 19 home runs at Manchester in the Class AA Eastern League in 1969, Blomberg was rewarded with a September call-up to the Yankees. He made his major league debut on September 10 at RFK Stadium. Called on to pinch hit for pitcher Bill Burbach in the top of the eighth inning, he drew a walk. Blomberg appeared in three more games, starting twice, and went 3-for-6. It was a small sampling of his ability, but a promising one.

While at Manchester, Blomberg met his future wife, Mara Goldsmith, during a series at Elmira. Mara was a senior at Syracuse University, and the next season, Blomberg was promoted to Syracuse in the AAA International League. The couple tied the knot on October 25, 1970, in Elmira.

In 1971, Blomberg began the season at Syracuse. He was batting .326 with six home runs and 20 RBIs when he was called up to the Yankees. An injury to Roy White opened a space on the roster and Blomberg took full advantage of the opportunity. He started in right field in a home game against Washington on June 25 and stroked a two-run homer off the Senators’ Pete Broberg in the bottom of the third inning. On the day, he was 2-for-5 with two hits, two RBIs and two runs scored in the Yankees’ 12-2 victory. Four days later he went 3-for-4 against Cleveland, driving in two more runs as New York pasted the Tribe, 9-2. He clubbed two home runs in a game at Minnesota on August 1 and again at Kansas City on August 28.

In 64 games, Blomberg batted .322, with seven home runs and 31 RBIs. He was in the major leagues to stay, but the Yankee franchise was in a downturn. Their last postseason appearance had been in 1964, when they lost in the World Series to St. Louis. Since then, New York had swiftly descended in the AL standings, finishing in last place in 1966. Expansion caused each league to be split into two divisions of six teams apiece. Now in the AL East, it was Baltimore who ruled the roost, as the Orioles claimed the division title in five of the first six seasons of divisional play.

Blomberg was switched to first base for the 1972 season, where he split time with Felipe Alou, starting 90 games. Right field was a revolving door with Johnny Callison, Rusty Torres, and Ron Swoboda splitting the majority of starts. Despite the new position, Blomberg still had a productive offensive season.

The following season, a new position was created, and it was one that made Ron Blomberg a household name. The designated hitter may have been created partially in response to the “Year of the Pitcher” in 1968 when hurlers dominated baseball. AL owners realized it was a 14-13 slugfest that put fans in the seats, not a 1-0 pitchers’ duel. In 1969, four minor leagues were given permission to experiment with using a substitute hitter. The leagues (Eastern, International, Texas and New York-Penn) called the new role “pinch-hitting specialist” or “wild- card pinch-hitter.”10 Each league used the new player with varying criteria. But it was the International League whose use of the “permanent pinch-hitter” that led to the designated hitter of today. After some initial dawdling and tinkering with the rules of the new position, the AL put the DH in play for the 1973 season.

The New York Yankees opened 1973 against arch-rival Boston at Fenway Park. Blomberg was penciled in as the sixth batter on Yankee manager Ralph Houk’s lineup card. Boston’s DH was Orlando Cepeda. The former NL star had signed with the Red Sox in the off season after playing a year in Oakland in 1972. Bosox skipper Eddie Kasko slated Cepeda to hit in the five-hole. The Yankee-Red Sox tilt was the first game scheduled on the AL docket.

Blomberg, a first baseman–outfielder, was unsure of what the new position entailed. “You get up to bat, you take your four swings, you drive in runs, you come back to the bench, and you keep loose in the runway,” Houk told him. “You’re basically pinch-hitting for the pitcher four times in the same game”11

With two down in the top of the first inning, the Yankees loaded the bases to bring Blomberg to the plate. The DH worked Boston starter Luis Tiant for a walk, driving in the first run of the season. But the visitors were shellacked, 15-5. After the game, His bat and his number 12 jersey were sent to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. Blomberg, who went 1 for 3 on the day, was quite surprised at the gathering of reporters at his locker. “If Ralph thinks I can help most by being the DH, then it’s all right with me,” he said. “I love to play, but I know I’m a better hitter than anything else. I am getting better, but I’m not a natural [as a complete player].”12

Blomberg was not the only DH in the Yankees’ lineup that season, nor was he the most utilized at that spot in the batting order as Jim Ray Hart started most games as the DH. But he had the finest offensive season of his career in 1973 with high marks in hits (99), runs (45), RBIs (57) and batting average (.329). New York (80-82) finished in fourth place in the East, 17 games behind first-place Baltimore.

Houk used a platoon system in some cases, and Blomberg was no exception. Against right-handed pitchers, he tore the cover off the ball. But against southpaws, he had little success. “Eventually, he’ll hit left-handed pitching, but now, he doesn’t have the same swing against them that he does against right-handed pitching,” said Houk. “Against left-handed pitching, he pulls away from the ball, he doesn’t even break his wrists.”13

The statistics support Houk’s statement. In 1973, Blomberg batted .338 (96-for-284) against righties and .176 (3-for-17) versus lefties. Blomberg was not receiving much of an opportunity to face southpaws. “Against the left-handers, I know if I never get a hit, I’m never going to see them again, and all that adds to pressure,” he said. “But some day, I’ll be in the lineup every day. I don’t want to have to look at the lineup every day to see if I’m in it. The pitching didn’t make any difference to me when I was growing up. But if you can hit, you can hit anybody.”14

There would be new faces on the field and off as the Yankees and Blomberg looked towards 1974. Houk resigned to take the managing job in Detroit. He was replaced by Bill Virdon, a center fielder for the Pirates in the 1960s who had managed the Bucs the previous two seasons. Yankee Stadium was shut down for two years as the ballpark underwent extensive renovations. The Yankees played their home slate at the Mets’ Shea Stadium for the 1974 and 1975 seasons.

The Yankees made three personnel moves, and each had a direct bearing on the playing time of Blomberg. On December 7, 1973, they acquired outfielder Lou Piniella and pitcher Ken Wright from Kansas City for pitcher Lindy McDaniel. Piniella, the 1969 AL Rookie of the Year, would be a mainstay in the outfield in New York for the next 11 years. On March 23, New York purchased outfielder Elliott Maddox from Texas. Maddox started in center field for most of the games (108) during the 1974 season. On April 26, 1974, they acquired first baseman Chris Chambliss, and pitchers Dick Tidrow and Cecil Upshaw from Cleveland in exchange for four pitchers: Fritz Peterson, Tom Buskey, Fred Beene and Steve Kline.

Like Blomberg, Chambliss was a left-handed batter, and he would be the starting first sacker for the next several seasons. The short right field porch at Yankee Stadium lent itself to being a cornucopia of home runs for left-handed hitters capable of developing a power stroke.

Virdon also employed a platoon system, using Bill Sudakis, Roy White, and Blomberg in the role of the DH. Eventually, Blomberg had to prove he could hit lefties, and Virdon gave him his chance. “If he goes 0-for-40 or even 0-for-25, I’ll get him out of there,” said Virdon, “I can’t keep him in there if I think he’s hurting the club. It wouldn‘t be fair to the other guys. But I want to find out if he can hit them, and I’m going to give him a good, long shot.”15

Blomberg responded with a .311 batting average, .276 against left-handed pitchers. It was a big improvement, and a giant obstacle overcome by Blomberg. Bolstered by a 38-21 record in August, September and October, the Yankees surged in the AL East standings. On July 31, New York sported a 51-52 record, tied with Milwaukee for fourth place. They finished the year with an 89-73 record in second place, two games behind Baltimore.

On October 22, New York shipped Bobby Murcer to San Francisco for Bobby Bonds. Murcer and Bonds were both outfielders who could hit the long ball and steal some bases, although Bonds was more proficient in each category. The Yankees were figuring that with Bonds, a right-handed batter in the lineup, they would face more right-handed hurlers. Thus, Blomberg would see some more action. “With Bobby Bonds in right field and three first basemen (Chambliss, Otto Velez, and Bob Oliver) I might as well donate my gloves to charity,”16 said Blomberg.

Injuries ended Blomberg’s time in the Bronx. On May 4, 1975, at Milwaukee, he suffered what was at first believed to be a right shoulder strain. The prognosis of missing a week of playing time turned into six weeks. Blomberg returned to the lineup in a month. On July 12 against Minnesota at home, he tore a muscle in his right shoulder in the third inning, and was done for the year. “I felt it tear when I swung and I knew I was in more trouble,” said Blomberg. “It felt as if I had been shot by a shotgun.”17

After some initial testing of the shoulder, doctors determined that the injured biceps muscle may heal on its own. By doctors’ orders, Blomberg wore a harness to immobilize his arm. After the harness was removed, surgery was not deemed necessary, and he spent four hours a day rehabilitating his shoulder. He seemed to make a splendid recovery, but he hurt his shoulder again in the final spring exhibition against the Mets. This time, the injury was in a different location and he traveled to California to have surgery on April 16 to mend the tendinitis in his biceps. It was hopeful he would return soon, but he appeared in only one game in 1976, on September 8. The season was especially bitter for Blomberg as the Yankees won the AL pennant, their first since 1964. But the Bombers were swept by Cincinnati in the World Series. One bit of good news was that Ron and Mara celebrated the birth of their son, Adam.

The following spring, with his shoulder healed, Blomberg was having an outstanding spring training. But on March 30, he was in the outfield when he gave chase to a line drive off the bat of Boston’s Doug Griffin. Blomberg recalled hearing Roy White yelling for him to “stop” before he ran into the concrete outfield wall. “The next thing I know, I’m walking around in circles on the bad leg, and there’s blood running down my nose,” said Blomberg. “Then I just started babbling, I guess. ‘I can play. I’m fine, don’t put me on the disabled list.’” But he was not fine, and needed surgery to repair four broken bones in his kneecap and torn cartilage. As a result of these injuries, Blomberg missed the entire 1977 season. The Yankees won the pennant again, and this time they topped the Los Angeles Dodgers in the World Series, capturing their first world title since 1962. Despite his absence, Blomberg’s teammates did not forget about him. He was given a full share of the winner’s pot, $27,758.04.18

Blomberg hit the free agent market and signed a four-year pact worth a reported $600,000 with the Chicago White Sox.19 Chicago was coming off a tremendous year in 1977. Dubbed “The South Side Hitmen” because of their prowess in hitting the long ball, the Sox finished in third place in the AL West with a 90-72 record.

In the season opener against Boston, Blomberg brought the fans at Comiskey Park to their feet when he connected for a solo home run in the bottom of the ninth inning to tie the score at 5-5. The White Sox tacked on another run in the ninth to win, 6-5. “The home run wasn’t the biggest thrill,” said Blomberg. “Just coming out on the field in a uniform and having the fans yelling at me was. After you’ve been on an operating table and they’ve taken half your body apart, you’re just happy getting your white uniform dirty again.”20

Blomberg’s Opening Day homer was the highlight of his year. Through the end of May, he was batting .203 and, after hitting three homers in April, he went without a home run for 18 games until he hit his fourth on June 15. He experienced some pain in his reconstructed right knee which contributed to diminished playing time.

It was not just Blomberg, as the White Sox as a team were not performing as they had in the past season. A 34-40 record at the end of June landed them in fifth place of the AL West, but just five games behind first-place Texas. On June 30, manager Bob Lemon was fired and replaced by Larry Doby. Blomberg appeared in only 61 games for the White Sox in 1978, batting .231 with five home runs and 22 RBIs. He was the victim of a platoon system once again, facing right-handed pitchers in 140 at bats and only 16 at-bats against lefties. His contract was the cause of much derision and booing from the Comiskey Park fan base.

The White Sox waived Blomberg at the end of spring training the following season. On March 30, 1979, his career came to a screeching halt. The club offered to send him to AAA Iowa, but Blomberg refused. “If Ron would just go spend a month or two at Des Moines, getting his stroke back, who knows?” said new Sox manager Don Kessinger. “He might have eight or nine years in the major leagues. I can’t blame him for wanting to catch on right away in the majors. I hope he does. I’d like to see what happens.”21

Although Blomberg liked the city of Chicago and its people, life was different in the White Sox clubhouse. “I didn’t blend in to the Chicago clubhouse as well as I had hoped. There were four or five guys on the team who never spoke to me and would not associate with me outside of the ballpark. Even though he was Jewish, my relationship was not good with pitcher Steve Stone. He did his own thing. In addition, there were a lot of born-again Christians on the team who held regular prayer meetings. They didn’t accept that I was Jewish and didn’t want me to get involved, even though the meetings were supposed to be non-denominational.”22

Blomberg’s career statistics included a .293 batting average with 52 home runs and 224 RBIs. He was at his best in the clutch, batting .296 with runners in scoring position and .319 as a pinch hitter.

In retirement, Blomberg has stayed close to the game he loved so much. He runs the Ron Blomberg Baseball camp in association with Total Specialty Camps, offering instruction in all facets of the game from the camp’s location in Milford, Pennsylvania.23 He is a yearly participant at the Yankees fantasy camp and one of the more popular instructors. In addition, he does some high school and college scouting for the Yankees from his suburban Atlanta home. In 2007, he was the manager of the Bet Shemesh Blue Sox of the first ever Israel Baseball League. In 2008, he and author Dan Schlossberg wrote his autobiography, Designated Hebrew, which was published by Sports Publishing.

In 2021, Blomberg, along with Dan Epstein, authored The Captain and Me: On and Off the Field with Thurman Munson. The book details the unlikely friendship between two teammates who were direct opposites. One was outgoing and talkative (Blomberg) and the other sullen and grumpy (Munson).

Blomberg is in high demand as a motivational speaker, telling his story of perseverance and his successes. He resides in Roswell, Georgia, with his second wife, Beth. They have one child, daughter Chesley.

Last revised: June 9, 2021

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by James Forr and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Mark Sternman.

Sources

In addition to the sources shown in the Notes, the author used Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Obituaries, Atlanta Constitution, April 22, 2961: 18.

2 Larry Ruttman, American Jews & America’s Game, (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2013), 244-245.

3 Peter Ephross with Martin Abramowitz, Jewish Major Leaguers: In Their Own Words, (Jefferson, NC: McFarland 2012), 156.

4 Jim Ogle, “Yanks Nab Top Pick Blomberg For $90,000,” The Sporting News, July 8, 1967: 13.

5 Ogle; and Ruttman,. American Jews & America’s Game: 242.

6 Ruttman, 242.

7 Able Goldblatt, “Is Blomberg the Next Mantle? Yankees Can Dream, Can’t They?” The Sporting News, May 11, 1968: 42.

8 Goldblatt: 42.

9 Jim Ogle, “Blomberg’s Wife Made Him Leave Slumps on Doorstep,” The Star-Ledger (Newark, New Jersey), July 15, 1971: 48.

10 Jack Lang, “Wild-Card Hitter to Get Trial in Four Minors – Majors Watch Closely,” The Sporting News, February 15, 1969: 45.

11 Ephross, 154.

12 Jim Ogle, “Blomberg’s First DH Bat Earns Cooperstown Niche,” The Sporting News, April 28, 1973: 17.

13 Dave Anderson, “The House that Blomberg Remodeled,” New York Times, June 2, 1973: 23.

14 Anderson.

15 Phil Pepe, “Blomberg Faces Lefties in Desperation Move,” The Sporting News, June 15, 1974: 16.

16 “Insiders Say,” The Sporting News, April 19, 1975: 6.

17 Red Foley, “Yankees Suspended Again; Ron Is Disabled,” New York Daily News, July 14, 1975: 52.

18 “Saga of Series Swag….$1,182 to $27,758,” The Sporting News, December 3, 1977: 57.

19 Jack Lang, “Blomberg to Sign Chi’s 600g Pact,” New York Daily News, November 15, 1977: 82.

20 David Israel, “Ron Blomberg Has a Blast,” Chicago Tribune, April 8, 1978: 2-1.

21 Richard Dozer, “Sox Give up on Ron Blomberg,” Chicago Tribune, March 31, 1979: 2-1.

22 Ephross, 166.

23 https://totalspecialtycamps.org/excel-in-sports/baseball/ Accessed March 21, 2021.

Full Name

Ronald Mark Blomberg

Born

August 23, 1948 at Atlanta, GA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.