Roy Johnson

Because he was born on an Indian reservation, Roy Johnson was considered a ward of the government. He and his younger brother Bob Johnson, who joined the Red Sox in 1944, were both born in Pryor, Oklahoma (some 35 miles east of Tulsa) – before Oklahoma became a state. Roy was the eldest of the two, born at home on the farm on February 23, 1903.1 They had six siblings, two other boys and four girls. Robert Lee Johnson was their father; he’d moved to the area from Missouri. Anna Blanche Downing was half-French, half-Cherokee. There are different stories suggesting why the family moved to Tacoma, Washington, but by the time of World War I, move there they did.2

Because he was born on an Indian reservation, Roy Johnson was considered a ward of the government. He and his younger brother Bob Johnson, who joined the Red Sox in 1944, were both born in Pryor, Oklahoma (some 35 miles east of Tulsa) – before Oklahoma became a state. Roy was the eldest of the two, born at home on the farm on February 23, 1903.1 They had six siblings, two other boys and four girls. Robert Lee Johnson was their father; he’d moved to the area from Missouri. Anna Blanche Downing was half-French, half-Cherokee. There are different stories suggesting why the family moved to Tacoma, Washington, but by the time of World War I, move there they did.2

Both brothers enrolled in Irving School and playing sandlot ball. It’s said they attended Tacoma High School, but biographers Patrick J. and Terrence K. McGrath report, “Nobody remembers the boys ever attending high school.”3 Roy himself completed a questionnaire for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and reported that he completed eight grades of school, and that’s all.

Roy began playing ball in Tacoma, in the City League around 1922, and eventually came to the attention of scouts. Sonny Bailey, a former classmate of both Roy and Bob, saw them as opposites: “Roy was a hot-headed guy; Bob was real quiet. Roy could run like a rabbit. He was actually a natural right-handed hitter but his coaches always had him bat left-handed to take advantage of that great speed. Years later, when he made the big leagues, they made motion pictures of him running and bunting.”4

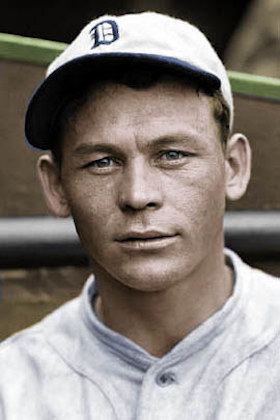

Roy Cleveland Johnson is listed as batting left and throwing right, standing 5-foot-9 and weighing 175 pounds. He was an outfielder throughout his career. There may have been a brief interlude, his first appearance in pro ball, with Tulsa in 1925, for just 10 games and just one hit. For the most part, however, he seems to have played semipro ball in Everett, Washington and in the San Francisco area from 1922-25, initially mostly as a pitcher (pitchers were typically paid better in semipro ball.) When he arrived in California looking for work, he declared he was an outfielder. Johnson was with a Southwestern Washington League team in Ellensburg, Washington in 1923 and 1924. He reportedly spurned an offer from the New York Yankees in 1924, because he preferred to stay in Washington. He signed with Seattle late that year but stayed on the bench and when he went to California to play winter ball, Seattle relinquished their claim.

One the semipro clubs with which he played winter ball in San Francisco was the 23rd Street Skidoos, where he was managed by I. E. “Shouting Shorty” Couch, who helped him get signed by the Pacific Coast League’s San Francisco Seals. In 1926 the Seals assigned his contract to Idaho Falls in the Class-C Idaho-Utah League. There he hit .369 with 19 home runs, and stole 17 bases. He scored more runs than there were games in which he played – 133 runs in 112 games. He was recalled to the Seals in August and got into 25 games, batting 260.

There had actually been some confusion before the 1926 season began, as to just who Johnson had signed with. He’d been playing with Everett, Washington, in 1924, but appeared in only two or three games. He was sent a contract for 1925 to the Tacoma address he had provided. It apparently never reached him, since he had gone south to play semipro ball around San Francisco. In any event, Couch seems to have helped him get signed by Seals scout Nick Williams. The problem was, he’d also signed a contract with Bill Cunningham of the Sacramento team.5 The San Francisco Chronicle called him “the boy who is so anxious to play ball that he signs whenever he gets a chance.”6 This was somehow worked out relatively quietly, after a period of controversy. The Chronicle reported he was playing well in winter ball; his team, the Foresters, won the title.

The Seals didn’t really need Johnson in their outfield in 1927; they had Lefty O’Doul, Earl Averill, and Smead Jolley. The PCL played a very long schedule; the Seals played 196 games that year. (They finished second.) Jolley hit .396. O’Doul had 278 base hits. Roy hit .311 in 78 games. O’Doul was league MVP, and drafted into the major leagues, opening up a spot for Johnson in 1928. And O’Doul had good words to say for him: “This fellow Roy Johnson should be a wonderful ball player. He is as fast as a streak and as strong as a young bull. He has a wonderful throwing arm and has tremendous power. He has natural ability enough to be a major league star.”7

Jolley won the Triple Crown and the Seals won the pennant. Jolley hit .404 and drove in 188 runs, with 45 home runs. Roy Johnson joined Jolley on the league All-Star team, though. Johnson hit .360, tied for the league lead in triples (again reflecting his speed), hit 22 homers, and scored 142 runs. And some seasoned observers, like columnist Bob Ray of the Los Angeles Times, felt that among Jolley and Averill, “Johnson…is the greatest prospect of the three…Johnson has the best arm in the league, is young and fast, and is now hitting above .350. What more could you ask of a young fellow in his first full season as a regular in AA ball?”8 As to his speed, a story that ran in the Boston Sunday Advertiser dubbed him “an accomplished purloiner of the second hassock.”9 He had stolen 25 bases in 1928.

On October 19 Bucky Harris was named the manager of the Detroit Tigers for 1929. His very first act was to announce the signing of Roy Johnson, who had been acquired from San Francisco for a reported $75,000.10 That was one of the highest amounts ever paid for one player at the time, and no doubt led to brother Bob looking to baseball as a way to make money. He’d been working as a fireman in Glendale, California.11 He now started to look around for opportunities in baseball. Roy looked to get a piece of the purchase price and held out a bit in the spring. It appears that he was unsuccessful, and reported.

While Roy was due to break in during 1929, Bob meanwhile signed with Wichita (Western League) in February.

Roy joined the Tigers for spring training in Phoenix, the last Tiger to do so. He had a terrific season with the Tigers. His debut was on April 18 and he pinch hit, without a hit, that day and the next (though he scored his first run on the 19th, after reaching on a fielder’s choice.) On the 20th, he started his first game and doubled in four at-bats, but committed two errors in the game. He made two more errors on the 23rd. He drove in his first two runs on the 26th. He drove in three more runs on the 27th, two of them on his first home run. As leadoff batter, his second homer was an inside-the-park one on May 18. Four of his homers in 1929 were leadoff ones; he hit eight of them in his career. An inside-the-park home run in the bottom of the 11th on August 11 won the game in a walk-off.

The 26-year-old rookie tied with Charlie Gehringer and Heinie Manush for the American League lead in doubles with 45. He hit for a .314 average, with 201 base hits (10 home runs), and scored 128 runs (second in the league). He drove in 69. The Tigers had a .299 team average, and scored 926 runs, but finished in sixth place largely because of a 4.96 earned run average. Roy was named as left fielder on The Sporting News’s All-Rookie team.

On November 9 he married Helen Lucille Fraser of San Francisco. Their first child, Marylyn, was born in 1932. They divorced later in life.

Sophomore slump? His average dropped in 1930, down to .275 in 125 games. He had eight hits in his first 15 at-bats, but then took 70 more at-bats (until May 24) to get his next eight. He had one RBI for the entire month of May. His RBI total dropped by almost 50%, down to 35.

Bucky Harris came close to trading him in 1931, and Johnson had to fight for his place in the outfield, but he came through and bumped things up a bit, leading the league in triples with 19 while hitting .279. Johnson stole 33 bases. Although never a very good fielder (his career fielding percentage was .938), he did have 25 outfield assists, matching his total in 1929.

He hit a “towering home run over the right-field fence” in Washington as the first batter on Opening Day in 1932, but Johnson declined sharply in June and was hitting only .251 when the Tigers traded him and Dale Alexander to the Red Sox for Earl Webb on June 13.12 It was quite a good trade for Boston, but not for the Tigers. Webb had set the still-standing record for doubles in 1931 — 67 — while batting .333. He never approached those figures again, hitting 28 in ’32 and just five in his final year, 1933. Alexander became the American League batting champion in 1932 and Roy Johnson hit .298 the rest of the year for the Red Sox. Even in doubles, Johnson (with 38) topped Webb (28). Interestingly, there was one day when Johnson showed he was indeed “a natural right-handed hitter.” In the first game on August 14, facing the Athletics’ Rube Walberg, Johnson batted right-handed and got three hits.13 He talked about becoming a switch-hitter, but there is no evidence he ever did.

Johnson drove his stats higher with the Red Sox: in 1933; he hit .313 and drove in 95 runs. Several of his hits were game-winners. For instance, his home run beat the Yankees on June 15, 1933 (which brought the Sox out of the A.L. cellar) and his two-run triple with two outs in the 10th beat the Tigers a week later, 9-7, on June 22. On July 13, his 11th-inning single knocked in the only run of the game, bearing the Tigers again, 1-0 at Fenway Park. The Red Sox finished seventh, only the third time they’d not finished last since 1921.

Bucky Harris, Johnson’s manager throughout his time with the Tigers, was hired as Red Sox skipper in 1934. Why did he think Johnson had started to hit again in 1933, showing the potential he’d first displayed in 1929?, Harris said he’d been a sucker for good pitching but “made great progress in the matter of picking good balls at which to hit. He taught himself to look them over.”14

In 1934 he had his best season, batting .320 with 119 RBIs (sixth in the league). The Red Sox finished in fourth place, their best showing since 1918. Run production dropped off sharply in 1935 (for the team, but more so with Johnson, who suffered shingles early in the season); nonetheless, he was consistent with his batting average, hitting .315.

For a team that was the last to field an African American, it’s of interest that the Red Sox in 1933, 1934, and 1935 had Native American Roy Johnson playing left field and Mexican Mel Almada playing center. Johnson played 26 games in left in 1933, but 95 in right field and 10 in center. In 1934, he played left field exclusively (137 in 1934 and 142 in 1935). Almada played sparingly in 1933 (13 games) and 1934 (23 games), but a full 126 games in center field in 1935. It was never a secret that Johnson was part-Cherokee. In reporting his 11th-inning homer that beat the Yankees on July 3, 1934, the Independence Day edition of the Boston Herald led by dubbing him “Cherokee Roy Johnson.”15 Almada was the first major leaguer born in Mexico. This fielding of the two was no commitment to diversity, but reflected an openness in signings that one wishes had been extended to other players of color.

Some of the newspapers, of course, played up the Indian angle. John Drohan of a Boston newspaper wrote about approaching Roy in the Red Sox dugout and holding up his right hand and saying, “How?” Then he asked, “How many base hits you ketchum today?” Roy, playing along (and it was in play), responded, “Injun no know, but him keep swingin’ just the same. He like white man pitcher, but if white man pitcher get ‘um mad, just too bad. Injun know you can’t get ’em hit with tomahawk on shoulder. But if Injun swing ’em, ketchum base hit.” How do we know this was all said in jest? After two more paragraphs of this farcical language, Drohan wrote: “‘Say cut it out,’ said Roy breaking into United States, ‘you’ll have me talking that way permanently.’”16

After four years averaging .313, Roy provided good trade bait and the Yankees were known to be after him. There were rumors during the fall of a three-way trade involving the Senators, Sox, and Yanks. On December 17, 1935, the Sox made a deal with the Senators, sending them Roy and Carl Reynolds for outfielder Heinie Manush. It was, per the Boston Herald, “the first player deal without money the dominating theme in which the Tom Yawkey-owned Red Sox have figured for a long time.”17 There was some thought that new Red Sox manager Joe Cronin wanted Manush, in part because the two had been roommates on the Senators. Of course, that Manush (a future Hall of Famer) had hit over .300 in 10 of his 13 years in the majors was no small consideration.18

It was another good deal for the Red Sox, because it proved out that Roy Johnson’s best days were behind him. Johnson never played for Washington, though; one month to the day he’d been traded, the Senators swapped him to the Yankees as part of a four-player trade on January 17, 1936. He apparently wasn’t pleased about the trades. Dan Daniel said he “was not one bit backward in expressing his chagrin over having been traded by the Red Sox.”19

Johnson hit just .265 for the Yankees in 1936, with only 147 at-bats. That’s the one time he saw postseason play, when the Yankees played against the Giants in the World Series. Johnson was used as a pinch runner in Game Three and reached second base as Frankie Crosetti singled in the go-ahead run in the bottom of the eighth, a 2-1 Yankees win. The inning ended when the next batter grounded out to first base. In Game Five, he pinch-hit but struck out.

He led the team in spring training and got in 12 games for New York at the beginning of 1937, mostly filling in for an ailing Joe DiMaggio, but once DiMaggio was ready, he was seen as surplus. Johnson was placed on waivers and picked up on May 11 by Boston’s National League team, the Bees; he appeared in 85 games (.277) for the Bees, where one of his outfield teammates was Vince DiMaggio.20 The sale provided an opportunity for Yankees prospect Tommy Henrich.

Johnson finished his time in the big leagues with the Bees in early 1938. His final appearance came on April 27. He was sold to the Milwaukee Brewers on May 12, four months before he would have become a free agent. The Globe said he’d come to spring training in excellent shape and torn it up during the exhibition season, but failed to hit as well once the regular season started. He was fortunate that the badminton “bird” which hit him in the eye during spring training with the Bees, only cost him four days in hospital. The Globe reported him as “disconsolate” and said he considered not reporting, but thought better of it.21

Roy’s lifetime average was .296, but the Red Sox had him for his best years. For the Red Sox, these had been interesting times. When Roy came in, it was in the 43-111 season of 1932. Tom Yawkey bought the club in early 1933, renovated Fenway Park before the 1934 season, and by 1935 the team was over .500. Roy Johnson contributed. He hit over .300 the three full seasons he played for Boston, and .298 the year he arrived mid-season. His four- year totals were 611 hits in 1,954 at-bats, for an average of .313. He hit 31 homers and knocked in 327 runs.

Bob versus Roy

Bob Johnson’s first year in the majors was 1933. He had already played against the Red Sox for 11 seasons before he came to Boston, for Philadelphia and Washington. “Indian Bob” was three years younger than Roy, and entered the big leagues four years behind him. His two years with the Red Sox were the war years of 1943 and 1944. Bob was playing for the Athletics, though, for the three full years that Roy was playing for Boston — 1933, ’34 and ’35. Bob hit for more power (288 HR to Roy’s 58, for instance) but, remarkably, both brothers wound up with identical .296 averages. If they really wanted to get down to it, though, Roy could lord it over his brother just a bit in batting average: Roy hit .2963982 and Bob came in second with .2963872.

Bob played 13 seasons compared to Roy’s 10. He also held a very significant edge in another area, being named seven times to the American League All-Star team. Roy was never so honored.

The first time the two brothers faced each other in major league play came on April 23, 1933, when the Athletics visited Fenway Park. Bob played right field for Philadelphia and batted fifth in the order, following Jimmie Foxx. He was 0-for-5 on the day, batting against an unrelated Johnson, Red Sox pitcher Hank. Roy Johnson batted second for the Red Sox, playing center field. He had a 2-for-5 day, with one RBI and one run scored. He committed two errors. The Red Sox won. Both Johnsons had two RBIs the next day, with Roy enjoying another 3-for-5 day, and Bob settling for a double and three runs scored.

Their paths would cross more than a few times in the four seasons they both played American League ball. They never played for the same team at the same time, but after the June 17, 1933, doubleheader in Boston, the two teams shared the same train west — the Red Sox heading to Cleveland and the Athletics to Detroit.

The following year, Bob hit a pinch-hit homer that gave the Athletics the lead in a game they won, 12-11. The four RBIs that Roy drove in kept the Red Sox close, but it was Bob’s hit that made the difference. There are numerous other times both played in the same game, but being on opposing teams didn’t affect their closeness. The two often spent time together in the off-season hunting and fishing.

Roy Johnson winds up his career

In 1938 Roy batted .301 in 128 games for the American Association Brewers. In 1939 he played in 127 games for Milwaukee and hit .296. That December, he was traded to Buffalo, though he wound up with Syracuse. He hit .269, perhaps a sign that at age 37 he was starting to decline. In 1941, Johnson played with Syracuse for seven games and then, after May 15, Baltimore, hitting .300 in a combined 77 games.

There were a number of unfortunate matters that came to pass. His marriage had ended in divorce. His younger brother Cecil died in a motorcycle accident, and Roy’s son took his own life in his early teens. His daughter also died at an early age.22

With World War II on in earnest, Roy Johnson spent 1942 and 1943 working in the San Diego Naval Shipyard. He also played some ball in the Shipyard League.23

His last two years in professional baseball were 1944, with the Seattle Rainiers (.260 in 111 games, an injured leg preventing him from getting started sooner in the season) and 69 more games in 1945, hitting .271. He was let go in June.

“Sadly, Roy Johnson’s later years were not spent in splendor,” write the McGraths. “Family members and acquaintances relate that Roy was not known to work and was not a stranger to alcohol.” Friend Ed Zigsworth said, “He lived reclusively [in Tacoma]…I think Bob was somewhat of a benefactor; very supportive.” Martin Kibler added, “He was living in an old shack when he passed away.”24 Roy Johnson died on September 10, 1973, in Tacoma. His death was reported diplomatically as due to a heart attack in The Sporting News, but the cause of death entered on the State of Washington death certificate was blunt: “Chronic Alcoholism.”

He had enjoyed one important recognition while still living. In 1960, he was inducted in the Tacoma-Pierce County Hall of Fame. Posthumously, he was inducted into the State of Washington Sports Hall of Fame in 1978.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author accessed Johnson’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Roy Johnson reported being “farm born” on his Hall of Fame player questionnaire. Other accounts locate the ranch at Spavinaw, Oklahoma, about 24 miles from Pryor. Spavinaw itself is the birthplace of Mickey Mantle.

2 Most of the information about the Johnson family comes from the exhaustively researched Bright Star in a Shadowy Sky: The Story of Indian Bob Johnson, by Patrick J. and Terrence K. McGrath (Pittsburgh: Dorrance Publishing, 2002).

3 McGrath and McGrath, 3.

4 McGrath and McGrath, 2, 3.

5 The Staff, “Sportitorials,” Seattle Daily Times, January 27, 1926: 23.

6 Ed R. Hughes, “Seals, At Boyes, Have Regular Game,” San Francisco Chronicle, February 23, 1926: 25.

7 Ed R. Hughes, “Gordon Slade Signs to Play with Missions,” San Francisco Chronicle, January 26, 1928: 23, 24.

8 Bob Ray, “Big League Scouts Have Eyes on Seals Gardeners,” Los Angeles Times, September 23, 1928: A4.

9 Al Nickerson, “Al’s Sports Sermonette,” Boston Sunday Advertiser, undated clipping in Roy Johnson’s Hall of Fame player file.

10 Associated Press, “Tigers Sign Harris, Former Washington Leader, As Manager,” New York Times, October 20, 1928: 15.

11 Associated Press, “Brother Detroit Flash Signed By Westerns,” Dallas Morning News, February 21, 1929: Part 2, 16.

12 The description of the home run was from the Associated Press. See San Francisco Chronicle, April 18, 1932: 13.

13 See Gene Mack cartoon, Boston Globe, August 15, 1932: 9, and “Play Against Walberg Makes Switch Batter of Detroit Gardener,” Dallas Morning News, December 25, 1932: Section II, 2.

14 Boston Herald, January 12, 1934: 37.

15 Edwin Rumill of the Christian Science Monitor once called him “the Swedish Indian from Oklahoma.” See Rumill, “Cubs Holding First Place by a Half-Game Margin as Series Opens Here Today,” Christian Science Monitor, July 14, 1937: 16. Dan Daniel also called him a “Swedish Indian” and a “Scandinavian Cherokee,” the latter perhaps being more accurate given his father’s reported Norwegian ancestry. See Daniel, “Both Yanks and Senators Should Benefit by Trade,” New York World-Telegram, date unclear (clipping in Johnson’s Hall of Fame player file.) On his player questionnaire, Johnson reported his ancestry as “Scotch, French, Cherokee Indian quarter breed.”

16 John Drohan, “Cherokee-Swede Smote Ball for .571 Against St. Louis and Chicago Teams,” unattributed, undated newspaper clipping, probably Boston Herald, in Bob Johnson’s Hall of Fame player file.

17 Burt Whitman, “Bucky Harris Predicts Grove Will Win 20 Games for Sox, Pacing Weiland, Ostermueller,” Boston Herald, December 18, 1935: 34.

18 James C. O’Leary, “Manush Gives Red Sox Batting Punch,” Boston Globe, December 18, 1935: 21, provided a good assessment of how the Sox saw the trade.

19 Daniel, “Chapman’s Job in Peril,” New York World-Telegram, March 26, 1938.

20 Yankees manager Joe McCarthy said the price was “a little better than the inter-league waiver price of $7,500.” Daniel, “Henrich Lands Yank Berth,” New York World-Telegram, May 12, 1937.

21 “Roy Johnson Is Sold to Brewers,” Boston Globe, May 13, 1938: 29.

22 McGrath & McGrath, 267.

23 McGrath & McGrath, 268.

24 McGrath & McGrath, 602, 603.

Full Name

Roy Cleveland Johnson

Born

February 23, 1903 at Pryor, OK (USA)

Died

September 10, 1973 at Tacoma, WA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.