Doc Medich

“[He] is what every boy wants to become and every mother dreams their daughter will bring home,” gushed sportswriter Phil Musick. “Tall, blond, handsome. Bright, articulate and personable. … He is Everyman’s vision of himself if he had been a little stronger, taller, handsomer, luckier, whatever.”1 Add to that list big-league pitcher and surgeon, too. His name was George “Doc” Medich, winner of 124 games in an 11-year career (1972-1982), and likely the last major-leaguer to be simultaneously a doctor. Here’s his story.

“[He] is what every boy wants to become and every mother dreams their daughter will bring home,” gushed sportswriter Phil Musick. “Tall, blond, handsome. Bright, articulate and personable. … He is Everyman’s vision of himself if he had been a little stronger, taller, handsomer, luckier, whatever.”1 Add to that list big-league pitcher and surgeon, too. His name was George “Doc” Medich, winner of 124 games in an 11-year career (1972-1982), and likely the last major-leaguer to be simultaneously a doctor. Here’s his story.

George Francis Medich was born on December 9, 1948, in Aliquippa, Pennsylvania. He was the only child of David and Esther (Mason) Medich. Nestled on the Ohio River about 25 miles northwest of Pittsburgh, Aliquippa of the post-World War II years was a booming industrial town, where an estimated 8,000 of the 27,000 residents worked in the steel industry.2 The elder Medich, a native Ohioan, settled in Aliquippa after serving in World War II, and soon found a job as a carpenter at the Jones & Laughlin steel mill, one of the world’s largest. George’s childhood was a microcosm of the baby-boomer idyll. His father’s job afforded the family a sturdy middle-class lifestyle; the Mediches were active members of St. Elijah Serbian Orthodox Church, and they loved sports. By the time George was 8, he was playing Little League baseball while attending Five Points elementary school. At Hopewell High School, George’s size (about 6-feet-4 as a senior) made him a three-sport star in football, basketball, and baseball as the seasons progressed. Upon graduation in 1966, he accepted a football scholarship to attend the University of Pittsburgh, where Aliquippa’s most famous son, Mike Ditka, had starred on the gridiron a few years earlier.

Given his size and speed, Medich played tight end and split end on Pitt’s football team from 1967 to 1969, during some of the leanest years (a combined 6-24 record) of the storied program’s existence. Smoky City sportswriter Russ Franke considered Medich an “excellent pass receiver” who had a good shot to be selected in the 1970 NFL draft.3 However, Medich’s interests had already drifted away from football by that time. He joined the varsity baseball team in 1969, and posted a 4-2 record (1.64 ERA), followed by another strong campaign (5-2, 2.43) in 1970 to earn consecutive berths on the Tri-State College All-Star team.4

Despite his passion for sports, Medich never let athletics define his identity. He was a pre-med student and let it be known that he wanted to attend medical school after graduation. Medich’s insistence on education and his career undoubtedly scared prospective baseball suitors. He was summarily dismissed by the Pirates at a tryout during his college years, but he wasn’t deterred. Instead, he sought advice from baseball’s most famous player-turned-physician, Bobby Brown, the New York Yankees former infielder who retired at the age of 29 in 1954 to pursue medicine full-time. “The scouts all assumed I wouldn’t play, but never bothered to ask me,” recalled Medich. “I wrote to Dr. Bobby Brown prior to the draft about the possibility of combining the two careers and he discouraged me.”5 The Yankees, however, were intrigued. Based on scout Randy Gumpert’s recommendation, they selected Medich in the 30th round, with the 700th overall pick, of the 1970 amateur draft, just weeks after he graduated with a degree in chemistry.6

Medich began his professional baseball career with a clear focus on medical school as his top priority. After making 12 combined starts with Oneonta in the in the Class-A New York-Penn League and Manchester (New Hampshire) in the Double-A Eastern League, Medich cut his season short to begin medical school at the University of Pittsburgh at the end of August. For the next two seasons, he missed spring training completely and reported late to his respective minor-league teams, raising questions about his commitment to baseball. “I knew that missing spring training would slow down my baseball a little,” he said, “but I was willing to make the sacrifice and so were the Yankees. I have no regrets.”7

The Yankees had a good reason to be flexible. Medich posted a 7-4 record and spiffy 2.43 ERA in just about two months of work with Kinston in the Class-A Carolina League in 1971. After the season, Medich organized a meeting between Yankees GM Lee MacPhail and Dr. Alvin Shapiro, associate dean of Pitt’s medical school. With a detailed plan, Medich convinced them that he could pursue both careers at once. “Everybody told me how it couldn’t be done, but they had blinders on,” recalled Medich. “It seemed like I was the only on who knew it could be done.”8

While Medich was finishing his second year of med school, MacPhail worked out a deal with the Pirates GM Joe L. Brown allowing Medich to pitch batting practice to the Pirates in April and May.9 The extra conditioning helped. Medich set the Eastern League on fire in his abbreviated stint with West Haven (Connecticut) in 1972, going 11-3 (1.44 ERA in 119 innings). Many wondered how good he could become if he had a spring training. The Yankees called him up to pitch in the 10th annual Mayor’s Trophy exhibition game against the New York Mets on August 24, at Yankee Stadium. Medich dazzled everyone by tossing a complete-game four-hitter to win, 2-1, and sealed his fate.10 On September 5, Medich made his big-league debut. Starting against the Orioles in Baltimore, he faced only four batters, yielding two walks and two singles, and was charged with two runs without retiring a batter. Any anxiety Medich had was justifiable – he had to report to medical school the next day.

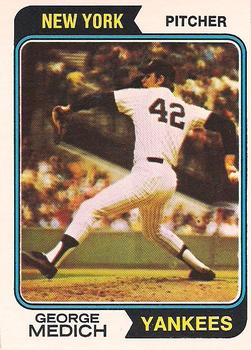

For the first time in his baseball career, Medich participated in spring training, in 1973, at the Yankees facility in Fort Lauderdale. Given the moniker Doc even though he had not yet completed his MD, Medich was a breath of fresh air on a stale club in the last vestiges of the so-called “Horace Clarke Years,” a period from 1965 to 1973 when the team usually floundered in the standings and at the gate searching for an identity after an unprecedented four-decade run of success. “Medicine has helped me to mature faster as a pitcher,” once said Medich. “In pursuing both careers simultaneously I had to be very careful in evaluating myself.”11 Medich never doubted his athletic ability, but also had a trump card few players had. Said Medich, “If I fail to make it as a pitcher, my life won’t be shattered.”12 He shouldn’t have worried. Medich emerged as the most effective rookie hurler and one of the brightest stars in baseball. For a sub-.500 club Medich went 14-9, completed 11 of 32 starts, and posted the fifth best ERA in the AL (2.95) in 235 innings. He finished with a flurry in September, hurling a three-hitter, a five-hit shutout, and an 11-inning no-decision, en route to a 1.51 ERA and 4-1 record in his final six starts. He finished tied with the Kansas City Royals’ Steve Busby for third in the AL Rookie of the Year voting, behind Baltimore’s Al Bumbry and the Milwaukee Brewers’ Pedro Garcia.

The Yankees’ baseball world was in chaos as the 1974 season got underway. Skipper Ralph Houk had resigned on the last day of the previous season, the same day Yankee Stadium saw its final home game for two years during which it underwent massive renovation. Home games were played at the Mets’ Shea Stadium. George Steinbrenner, who had purchased the Yankees in early 1973, was involved in offseason legal battles with the Oakland A’s because of his attempt to hire their former manager, Dick Williams, who was still under contract. Unable to secure Williams from the A’s, Steinbrenner hired no nonsense Bill Virdon, the Pirates’ ex-pilot, instead. Medich took in the drama with the detachment of an outsider aggravating baseball’s old guard who wanted players to fit the mold of a rah-rah jock, which Medich never was. “I have an advantage over most of these fellas because baseball is not the only thing that matters to me,” he said. “But this doesn’t mean I have a cavalier attitude toward the game. I hate to lose as much as anybody. But I can temper losing because I know I have a career in medicine.”13

After a shaky spring, Medich got off to a hot start, winning five of his first six decisions. When the longtime stalwart and last remnant of the Yankees glory years, Mel Stottlemyre, injured his shoulder on June 11, 25-year-old Medich assumed the mantle of staff ace. At 6-foot-5 and 225 pounds, Medich cut an imposing physical presence on the mound, but was not an overpowering pitcher (he fanned 10 or more in a game only once in his career); instead, he depended on ball movement and control for his success, and never shied away from pitching to contact. On July 20, he held the Royals hitless for eight innings before yielding a single on his first pitch of the ninth to Fran Healy, eventually settling for a 6-2 win. It was closest Medich ever came to a no-no in the majors, though he did throw one for Kinston, “where the lights were bad,” he said.14 Snubbed for All-Star Game despite his 12-7 record, Medich continued his torrid July in his first start after the midsummer classic by hurling a five-hit shutout to conclude a five-start stretch with five complete-game victories (1.20 ERA) and was named the AL Pitcher of the Month. His most important victory of the season, described as an “extraordinary effort” by Times sportswriter Gerald Eskenazi, was a five-hit shutout against the Brewers in New York on September 4 to put the Yankees in first place, tied with Boston.15 It was first time since October 1, 1964, that the team had occupied the top position so late in the season. The Yankees finished in second place in the AL East, two games behind the Orioles, but their future looked bright. Matching teammate Pat Dobson’s 19-15 slate, Medich completed 17 of 38 starts with a 3.60 ERA in 279⅔ innings.

The Yankees’ success and the offseason acquisitions of free agent Catfish Hunter, and Bobby Bonds in a trade with the San Francisco Giants for clubhouse leader Bobby Murcer led to elevated expectations in 1975; however, the season was anything smooth sailing. Honored as Opening Day starter, Medich was shelled for five runs in 5⅔ innings in a 5-3 loss to the Indians in Cleveland on April 8. That game marked the debut of the first African-American manager in baseball history, Frank Robinson, who belted a home run in his first at-bat. Medich rebounded with three consecutive complete-game victories, including a two-hit and a three-hit shutout, only to lose six straight starts while his teammates provided seven total runs of support. The Yankees’ offense, featuring Graig Nettles, Chris Chambliss, Thurman Munson and Bonds, was thought to be among the league best, but it underperformed all season, while the Yankees struggled to play .500 ball. On August 1, Steinbrenner, who had been suspended by Commissioner Bowie Kuhn in late November 1974 for two years for illegal contributions to President Richard Nixon’s political campaigns, replaced Virdon with Billy Martin. That move only exacerbated tension in the clubhouse that seemed at times to border on open mutiny. “Everything’s been falling apart,” said Medich, who expressed his sympathy for Virdon. “The attitude is really bad. … We [don’t] have any enthusiasm. … It seems like nobody’s really concentrating and I don’t think everybody’s putting out. We’re just going through the actions.”16 Medich won five times in September to finish the campaign with a 16-16 slate and 3.50 ERA in 272⅓ innings for the third-place club.

On December 11 Medich was shipped to the Pittsburgh Pirates in a blockbuster deal for pitchers Dock Ellis and Ken Brett and highly-touted second-base prospect Willie Randolph. The trade proved to be one of the worst in Pirates history. While Randolph emerged as a perennial All-Star and the disgruntled Ellis won 17 games, Medich failed to live up to expectation as an innings-eater capable of winning 20 games. A day after his no-decision as the Opening Day starter against the Phillies in Philadelphia on April 10, Medich’s other professional instincts took over when he rushed into the stands at Veterans Stadium to administer CPR to an elderly man having a heart attack. [A similar scene occurred two years later when Medich performed life-saving CPR on a heart-attack victim at Municipal Stadium in Baltimore.17] In his debut at Three Rivers Stadium on April 16, Medich tossed a complete game against the Mets for his first Bucs victory. “Pitching in my hometown for the first time meant an awful lot to me,” said Medich. “I felt a lot of pressure to pitch well and did.”18 Perhaps the pressure was too much. Between May 31 and August 15, Medich won only one time. That stretch, however, included one of the best games in his career, 10 innings of scoreless five-hit ball against Tom Seaver and the Mets that ended in a Pirates 1-0 win in 13 innings. Pitching coach Dave Osborn thought Medich nibbled too much, “trying to hit spots,” leading to poor control and inconsistency.19 Medich rejected that diagnosis. “I’m not an overpowering pitcher,” he declared. “I don’t have a fastball like Nolan Ryan or a breaking pitch like Bert Blyleven. I have to pitch to spots.”20 Frustrated with his hurler, manager Danny Murtaugh shunted him to the bullpen in mid-August, and Medich made only one start over a four-week stretch. Medich concluded his lackluster campaign with an 8-11 record and 3.51 ERA in 179⅓ innings for the second-place Bucs.

Just weeks after completing his medical degree at the University of Pittsburgh, Medich was unexpectedly sent along with five other players (notably young slugger Tony Armas and pitcher Rick Langford) to the Oakland A’s in exchange for Phil Garner and two others on March 15. Medich, who had not signed his 1977 contract in order to become a free agent at the end of the season, was livid. “I’m really kind of fed up with the Pirates. I’ve burned my bridges,” he vented. “They demand loyalty from the players, but it’s a two-way street. If they can’t respect you, I can’t respect them. They really screwed up my life.”21 Set to begin his medical residency in Pittsburgh that fall, Medich threatened to quit baseball rather than move across the county, but ultimately reported to the A’s.

Medich desired stability; instead, he found himself in five different baseball uniforms in less than 12 months. As to be expected, the cerebral and ofttimes outspoken Medich clashed with the A’s owner Charlie Finley, who had the hurler on the trading block as soon as the season commenced. Pitching inconsistently for the eventual last-place club, Medich won five straight decisions from August 22 to September 10 to improve his record to 10-6. When it became clear that he would not sign a contact with the A’s, Finley sold him on September 13 to the Seattle Mariners, but Medich barely had time to unpack his bags. He was with the club only two weeks, long enough to win his only two decisions. In his Mariners debut on September 16, he tossed a complete-game seven-hitter to snap the Kansas City Royals’ 16-game winning streak, the majors’ longest in 24 seasons. “After I pitched my last game for Seattle,” said Medich about yet another twist to his weird season, “I headed home to Pittsburgh when a guy from the Mets called and said they had claimed me on waivers (on September 26).”22 As fate would have it, the Mets were playing in Pittsburgh. In his only appearance as a Met, Medich hurled seven innings and yielded three runs, but picked up the loss. “I got $12,000 in moving expenses from (the Mets) and never set foot in New York,” joked Medich.23 His combined 12-7 slate was offset by the ninth-highest ERA among qualified starters (4.53 in 177 innings) in both leagues.

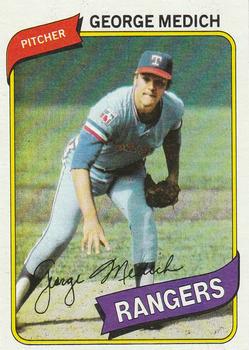

On November 11, free agent Medich signed a lucrative four-year deal worth $1 million with the Texas Rangers. Coming off a second-place finish in the West Division, the Rangers had also added All-Star pitchers John Matlack and Fergie Jenkins in trades and slugger Richie Zisk via free agency and were predicted to compete for divisional crown in 1978. Medich had a “disappointing” spring training, according to beat reporter Randy Galloway, casting doubts on his spot in the rotation.24 After he was clobbered in his first two regular-season starts, he was relegated to the bullpen, making only one start in a seven-week period. He subsequently tossed a few gems, such as a seven-hit shutout against the California Angels on June 25 to increase the Rangers’ divisional lead to one game; and blanked the Boston Red Sox on two hits on July 26, ending the club’s eight-game skid. The Rangers staff finished with the second lowest ERA in the league (3.36), but their offense lacked the firepower to compete with Royals, who captured their third straight crown. Medich posted a 9-8 record and logged 171 innings with a 3.74 ERA, just below the league average of 3.76.

On November 11, free agent Medich signed a lucrative four-year deal worth $1 million with the Texas Rangers. Coming off a second-place finish in the West Division, the Rangers had also added All-Star pitchers John Matlack and Fergie Jenkins in trades and slugger Richie Zisk via free agency and were predicted to compete for divisional crown in 1978. Medich had a “disappointing” spring training, according to beat reporter Randy Galloway, casting doubts on his spot in the rotation.24 After he was clobbered in his first two regular-season starts, he was relegated to the bullpen, making only one start in a seven-week period. He subsequently tossed a few gems, such as a seven-hit shutout against the California Angels on June 25 to increase the Rangers’ divisional lead to one game; and blanked the Boston Red Sox on two hits on July 26, ending the club’s eight-game skid. The Rangers staff finished with the second lowest ERA in the league (3.36), but their offense lacked the firepower to compete with Royals, who captured their third straight crown. Medich posted a 9-8 record and logged 171 innings with a 3.74 ERA, just below the league average of 3.76.

Described as the “perennial forgotten man” by sportswriter Galloway, Medich was relegated by manager Pat Corrales to mop-up duty for the first 2½ months of the 1979 season.25 With an 8.27 ERA in 20⅔ innings, his spot on the team was in jeopardy. Making his first start on June 24, in the second game of a twin bill against the A’s, Medich pitched seven effective innings to pick up his initial victory of the season and moved back into the rotation. He won four of five starts in July, and then kicked off a four-start winning streak on August 30 with a two-hit shutout against the Red Sox. Going against Boston in Fenway Park is “like pitching in a shower stall where you reach out and touch four walls,” he quipped.26 Medich’s turnaround and final line (10-7, 4.17 ERA in 149 innings) offered the Rangers a ray of hope for 1980.

Medich overcame pain in his elbow during spring training in 1980 to have his most productive season since he was a Yankee. After tossing a complete-game six-hitter to beat the Milwaukee Brewers, 8-1, on June 18 for his third straight victory, improving his record to 7-3, Medich was described by Galloway as the “best pitcher” on the club.27 The now 31-year-old reached a personal milestone on September 7 when he collected his 100th victory, securing all but the final out against the Brewers in a 7-2 win at County Stadium. Medich (14-11), reached the 200-inning plateau for the fourth and final time in his career, posting a 3.92 ERA in 204⅓ innings for a sub-.500 team.

On June 12, 1981, major-league baseball experienced its first work stoppage since 1972, following a unanimous vote by the players union, the Major League Baseball Players Association, to strike. While many players enjoyed their time off or worried about their future, Medich returned to Pittsburgh to continue his medical residency. Medich, who had pitched consistently before the strike, showed no signs of rust when the season resumed on August 9, yielding just a single earned run in his first three starts (and 22⅓ innings), including a six-hit shutout against the Toronto Blue Jays in Canada on August 24. On September 24, he flirted with a no-hitter for 7⅔ innings against the Twins in the Texas heat before surrendering a single to Sal Butera. Medich settled for his fourth career-two-hit shutout. It also proved to be his last of 16 whitewashings. He lost a heartbreaker to the Mariners, 2-1, in his next start, yielding an RBI single in the 11th. Medich finished the campaign with a 10-6 record and a robust 3.08 ERA in 143⅓ innings, and tied three other hurlers for the AL lead with four shutouts.

Prior to arriving at spring training, Medich announced that 1982 would be his 11th and final big-league season. At 33, he was ready to turn attention full-time to his medical career. The last chapter of Medich’s baseball life was a difficult one. In late February, he was diagnosed with hepatitis, which cast doubt on his readiness for Opening Day. Defying expectations, he was on the mound three weeks later for an exhibition game, but came down with elbow and then shoulder pain. Laboring through an arduous campaign, Medich lost four straight starts, culminating with a shellacking on August 9 in Milwaukee in which he yielded six runs in five innings, to drop his record to 7-11 with a 5.06 ERA. Two days later Medich went from last place to first place when he was sold in a waiver transaction to those same Brewers. “It’s nice to be with a team that’s in first place for a change rather than chasing somebody,” said Medich. “I’ve been in that situation throughout my career.”28 In his second start for the “Brew Crew,” Medich tossed three-hit ball over seven scoreless innings against the Mariners. His first Brewers victory was also a significant milestone for Rollie Fingers, who hurled two innings, becoming the first reliever to record 300 saves. Medich went 5-4 (5.00 ERA) as the fourth starter for skipper Harvey Kuenn’s explosive club, affectionately known as “Harvey’s Wallbangers,” who captured their first division crown.

Medich was relegated to the bullpen in the playoffs in favor of Moose Haas, whose place in the rotation he had originally taken. Medich did not see action in the Brewers’ exciting ALCS victory in five games against the California Angels, and made just one appearance in the World Series against the St. Louis Cardinals. With the Brew Crew trailing, 7-0, in Game Six, Medich entered in mop-up duty in the sixth inning, which might be the longest inning in World Series history. In what proved to be his last big-league game, Medich unraveled on the biggest stage in baseball. He yielded a double and two singles, walked one, and threw two wild pitches resulting in one run before he retired a batter. After Ozzie Smith grounded out, the game was delayed by rain for 2 hours and 13 minutes. When it resumed, Doc was back on the mound, but it didn’t get any better. By the time the inning was over Medich had been tagged for five hits and six runs (four earned). Medich set down the side in order in the seventh and then stepped off the mound for the last time. The Brewers lost Game Seven, in St. Louis, 6-3.

Medich announced his retirement after the Brewers’ defeat in the fall classic and returned to Pittsburgh and his family. “It was the travel more than anything,” he said. “I had played 10 years and planned on playing five, I wasn’t one of those guys who they had to tear the uniform off of.”29 While an undergraduate at Pitt, he had met Donna Lynn Creekmore, whom he married in June 1970, and together they had two children, Kelly and Mickey.

Medich compiled a 124-109 record and logged 1,996⅔ innings with a 3.78 ERA in parts of 11 seasons. He was especially tough on Amos Otis (8-for-67, .119 batting average), Brooks Robinson (3-for-21, .143), and George Scott (9-for-51, .176); and had trouble with Lyman Bostock (13-for-27, .481), Boog Powell (12-for-27, .444), and Rod Carew (21-for-49, .429).

Medich’s transition to full-time medicine was not as easy as expected. “I had an opportunity to be a team doctor but didn’t want to do it,” explained Medich. “Team doctors kind of get abused. It’s a tough enough job without having divided loyalties.”30

About a year after his retirement from baseball, Medich made national headlines as a resident in orthopedic surgery at Children’s Hospital in Pittsburgh when he was arrested in November 1983 for writing illegal prescriptions. Medich revealed to the media that he had been addicted to painkillers and muscle relaxers stemming from his elbow and shoulder pain and the stress of a pennant race during his last season in baseball.31 “You never really know when you’ve crossed the line, when you’re using it or it’s using you,” said Medich about his addiction, which ultimately led to his admission to a treatment facility. “I think I came to realize that I really had a problem after I quit playing.”32 In March 1984 he plead guilty to charges and was given a two-year suspended sentence and fined but his medical license was not revoked.

Medich went on to a long career as a respected orthopedic surgeon with a private practice in the greater Pittsburgh area. He never fully overcame his demons with dependency. In 2001, he was charged with and convicted on a similar offense, and given nine years’ probation.

As of 2017, Doc Medich still resided near Pittsburgh.

Last revised: September 20, 2017

Acknowledgements

This biography was reviewed by Len Levin and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also accessed Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, SABR.org, The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record, and the player’s file from the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York.

Notes

1 Phil Musick, “Medich Loose, Ready,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, March 9, 1977: 18.

2 Nicole Crowder, “Part I. Life and Slow Death of a Former Pennsylvania Steel Town,” Washington Post, November 4, 2015. washingtonpost.com/news/in-sight/wp/2015/11/04/the-former-steel-town-that-dimmed-its-light-to-help-pittsburg-shine/?utm_term=.19f008572472.

3 Russ Franke, “Panthers’ Senior Pack of 21 Hates to See It All End Now,” Pittsburgh Press, November 20, 1969: 49.

4 Baseball statistics from junior year are from “Panther 9 Will Play 33 games,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, March 11, 1970: 22; statistics from senior year are from “Two Panthers on Star Nine,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 10, 1970: 25.

5 Jim Ogle, “Doc Medich Could Cure Yankee Mound Aches,” The Sporting News, April 14, 1973: 19.

6 Jim O’Brien, “Doc Medich: He’s Good Medicine for the Yankees,” Baseball Digest, February 1975: 72.

7# Murray Chass, “Medich Pitching Way to M.D, Learns as Yankees Are Beaten,” New York Times, March 25, 1973: 237.

8 Steve Wulf, “How I Spent My Summer Vacation,” Sports Illustrated, June 29, 1981.

9 Charley Feeney, “Playing Games,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, September 2, 1972: 8.

10 Deane McGowen, “Yanks Beat Mets, 2-1, on Rookie’s Pitching and a Homer by Ellis,” New York Times, August 25, 1972: 23.

11 Don Anderson, Doc Medich and Pennant Trauma,” New York Times, October 1, 1974: 49.

12 Ogle, “Doc Medich Could Cure Yankee Mound Aches.”

13 Bill Christine, “Medich Chief Surgeon in Cutting Down Brewers Bats,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 12, 1974: 26.

14 Joe Durso, “Medich Misses No-Hitter in 9th As Yanks Vanquish Royals, 6-2,” New York Times, July 21, 1974: 177.

15 Gerald Eskenazi, “Brewers Lose on Medich’s 5-Hitter,” New York Times, September 5, 1974: 47.

16 Murray Chass, “Medich and Lyle Are Critical of Yankee Poor Performance,” New York Times, August 26, 1975: 25.

17 United Press International, “Doc Medic Registers Big ‘Save,’” Pittsburgh Press, July 18, 1978: 35.

18 David Fink,” Doc Takes Bow, Waves to Folks,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 17, 1976: 6.

19 Charley Feeney, “Too Much Nibbling by Doc,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 30, 1976: 11.

20 Charley Feeney, “Bucs Count on Medic to Step Up Win Pace,” The Sporting News, July 24, 1976: 11.

21 Vito Stellino, “Doc Medich Prescribes Loyalty Shot for Pirates,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, March 22, 1977:10.

22 Scott Zucker, “First Hitters, Now Patients Get Medich Treatment,” USA Today Baseball Weekly, August 12, 1997.

23 Ibid.

24 Randy Galloway, “Halt Dealing, Hunter Begs Rangers Boss Corbett,” The Sporting News, April 22, 1978: 26.

25 Randy Galloway, “Doc Gives Puny Texas First Aid,” The Sporting News, July 5 1980: 33.

26 Associated Press, “Royals Take First in West Away from California,” Odessa (Texas) American, August 31, 1979: 10.

27 Galloway, “Doc Gives Puny Texas First Aid.”

28 Tom Flaherty, “Medich Joins Brewers; It’s Last Place to First Place,” The Sporting News, August 23, 1982: 23.

29 Zucker.

30 Ibid.

31 Jim Gallagher, “‘Doc’ Medich to Face RX Charges,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, November 15, 1983: 8.

32 Danny Robbins, “Medich Works on a Comeback,” Los Angeles Times, March 18, 1984.

Full Name

George Francis Medich

Born

December 9, 1948 at Aliquippa, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.