Mel Stottlemyre

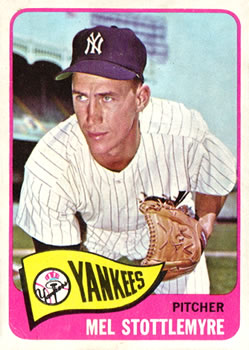

A baseball lifer, Mel Stottlemyre burst on the scene as a midseason call-up for the New York Yankees in 1964, helping the club win its fifth consecutive pennant and starting three games in the World Series. One of the most underrated and overlooked pitchers of his generation, Stottlemyre won 149 games and averaged 272 innings per season over a nine-year stretch (1965-1973) that corresponded with the nadir of Yankees history. Only Bob Gibson (166 victories), Gaylord Perry (161), Mickey Lolich (156), and Juan Marichal (155) won more during that period; only Perry tossed more innings, and only Gibson fired more shutouts (43) than Stottlemyre’s 38. Stottlemyre was the “epitome of Yankee class and dignity,” wrote longtime New York sportswriter Phil Pepe. “[He was] a throwback to a winning tradition in those years of mediocrity.”1 After a torn rotator cuff ended his playing career at the age of 32 in 1974, Stottlemyre embarked on a storied career as a big-league pitching coach, most notably for the New York Mets (1984-1993) and Yankees (1996-2005). Denied a championship as a player he won five as a coach (1986, 1996, 1998-2000).

A baseball lifer, Mel Stottlemyre burst on the scene as a midseason call-up for the New York Yankees in 1964, helping the club win its fifth consecutive pennant and starting three games in the World Series. One of the most underrated and overlooked pitchers of his generation, Stottlemyre won 149 games and averaged 272 innings per season over a nine-year stretch (1965-1973) that corresponded with the nadir of Yankees history. Only Bob Gibson (166 victories), Gaylord Perry (161), Mickey Lolich (156), and Juan Marichal (155) won more during that period; only Perry tossed more innings, and only Gibson fired more shutouts (43) than Stottlemyre’s 38. Stottlemyre was the “epitome of Yankee class and dignity,” wrote longtime New York sportswriter Phil Pepe. “[He was] a throwback to a winning tradition in those years of mediocrity.”1 After a torn rotator cuff ended his playing career at the age of 32 in 1974, Stottlemyre embarked on a storied career as a big-league pitching coach, most notably for the New York Mets (1984-1993) and Yankees (1996-2005). Denied a championship as a player he won five as a coach (1986, 1996, 1998-2000).

Melvin Leon Stottlemyre was born on November 13, 1941, in Hazleton, Missouri, the third of five children born to Vernon and Lorene Ellen (Miles) Stottlemyre. Vernon was a pipefitter and moved the family from south-central Missouri to Oregon and South Carolina before settling in the early 1950s in Mabton, a small farming town in Washington’s Yakima Valley, where he was employed at the Hanford Atomic Energy plant. The elder Stottlemyre, a former sandlot player, introduced Mel and his younger brother, Keith, to baseball and took them to local semipro games. According to his autobiography with John Harper, Pride and Pinstripes, Mel spent countless hours as a teenager in his backyard with his brother replaying the New York Yankees and Brooklyn Dodgers games they read about.2 Growing up in a blue-collar family in a rural area, Mel’s experience with baseball in organized leagues was limited until high school. The tall, bashful right-hander with sandy blond hair pitched and occasionally played shortstop for Mabton High School, which had just 10 players when he graduated in 1959.

On the strength of a 13-0 record as a senior, Mel accepted a scholarship to attend Yakima Valley Junior College, but got off to a rough start both in school and on the diamond. Declared academically ineligible because of poor grades in 1960, he played in a local summer league. He returned to the junior college in 1961 and went 7-2 for legendary coach Chuck “Bobo” Brayton.3 Stottlemyre worked out for the Milwaukee Braves at their minor-league affiliate in Yakima, but was rejected because he didn’t throw hard enough. While toiling on a farm and resigned that his baseball days were probably over, he was surprised by a visit from Yankees scout Eddie Taylor. With no negotiations and no bonus but unequivocal support from his folks, Stottlemyre signed a minor-league contract with his favorite team. “He had the effortless way of throwing the ball,” recalled Taylor.4

Just 19 years old, the unheralded Stottlemyre began his professional baseball career splitting his time with the Class-D Harlan (Kentucky) Smokies in the Appalachian League and the Auburn (New York) Yankees in the New York-Penn League in 1961. A combined 9-4 record and 3.27 ERA in 99 innings earned him a promotion to Class-B Greensboro in 1962. Described by sportswriter Moses Crutchfield as the “hottest prospect” in the Carolina League, Stottlemyre relied on a fastball, slider, and sinker to post a 17-9 record with a stellar 2.50 ERA in a league-leading 241 innings, including a stretch of 28⅔ scoreless frames early in the season.5 “His biggest asset,” wrote Crutchfield, “is his ability to keep the ball low.”6 That quality turned out to be Stottlemyre’s calling card to the big leagues.

The Yankees brass was impressed with Stottlemyre’s unexpectedly quick progress. He was invited to participate in spring training in 1963 as a nonroster player and was subsequently assigned to the Triple-A Richmond Virginians (International League). The youngest player on the club, Stottlemyre struggled against seasoned competition, posting a 7-7 record and splitting his time between starts (16) and relief appearances (23). The Yankees, fresh off a 104-win season that ended in a drubbing by the Los Angeles Dodgers in the World Series, did not invite the 22-year-old to spring training in 1964. Stottlemyre began the season in the bullpen for Richmond, but the lanky righty scuttled those plans by tossing a shutout in a spot start on Memorial Day. He worked his way into the rotation and won 10 consecutive decisions, earning a berth on the league’s All-Star team.

While Stottlemyre was leading the IL in wins (13), ERA (1.42), and shutouts (6), the Yankees were in a tense, three-way battle with the Baltimore Orioles and the Chicago White Sox for the 1964 pennant. When longtime ace Whitey Ford went down with a hip injury in late July, New York called up Stottlemyre, who arrived on August 11.

Stottlemyre’s debut on August 12 was “movie script stuff,” wrote New York sportswriter Til Ferdenzi.7 The rookie tossed a complete-game seven-hitter to defeat Chicago, 7-3. In what developed into a refrain heard over the next decade, hitters pummeled Stottlemyre’s sinker into the ground all afternoon. “He sure knows how to serve up those grounders,” said batterymate John Blanchard as the Yankees recorded 19 groundouts.8 Stottlemyre’s fairy tale continued throughout the regular season. On September 17 he recorded his seventh victory in nine starts to give the Yankees a psychological boost by pushing them into first place, tied with the Orioles and White Sox, for the first time in almost six weeks. Nine days later, he blanked the Washington Senators at D.C. Stadium on two hits (his first of seven career two-hitters) and tied a big-league record for pitchers by collecting five hits (four singles and a double). The Yankees’ most effective hurler, Stottlemyre finished the campaign with a 9-3 record and a team-best 2.06 ERA in 96 innings. Most importantly, Stottlemyre stabilized a shaky staff and helped the club win 34 of its final 52 games and capture its fifth consecutive AL pennant.

After the Yankees’ loss in Game One of the World Series against the St. Louis Cardinals, Stottlemyre tossed a seven-hit complete game, defeating hard-throwing Bob Gibson, 8-3, at Sportsman’s Park. “The kid’s got the best sinker and curve I’ve seen,” said Cardinals third baseman and NL MVP Ken Boyer. “There isn’t a pitcher in the National League with this kind of stuff.”9 Facing Gibson again, in Game Five at Yankee Stadium, Stottlemyre held the Redbirds to six hits and two runs (one earned), but was lifted for a pinch-hitter with New York trailing 2-0 in the bottom of the seventh in an eventual 5-2 defeat in 10 innings.

Then first-year skipper Yogi Berra sent the 22-year-old Stottlemyre on two days’ rest to face “Gibby” for the third time with the championship on the line. In the fourth inning, with two on and no outs, Stottlemyre induced Tim McCarver to ground into what appeared to be an easy double play. While covering first, Stottlemyre hurt his shoulder diving for a poor throw by Phil Linz, filling in for Tony Kubek at shortstop. Boyer scored on the play, and the floodgates were open. Stottlemyre surrendered two more singles and two runs (one on McCarver’s steal of home on the front end of a double steal), and was lifted for a pinch-hitter the next inning. “The fielders sabotaged [him],” wrote Yankees beat reporter Leonard Koppett of Stottlemyre’s performance in Game Five and Seven. “His hitters didn’t make a run while he was in the game. With a little support, Stottlemyre could have been the hero.”10

The Yankees’ 7-5 loss in Game Seven marked the end of an era. After winning 29 AL pennants and 20 World Series from 1921 to 1964, the team embarked on what historian Robert W. Cohen called the “lean years” over the next decade.11 A new era had indeed dawned. The Yankees were an aging club that had failed to sign top African American prospects, unlike other teams around baseball, including their opponents in the 1964 World Series. Although New York led the AL in attendance in 1964, its average of 15,922 per game was the club’s lowest since 1945 and suggested Americans’ general lack of interest in major-league baseball. At the end of the season, CBS purchased 80 percent of the team from owners Dan Topping and Del Webb. Stottlemyre’s emergence as a bona-fide big-league ace corresponded with the Yankees’ plunge to depths not witnessed since before the acquisition of Babe Ruth for the 1920 season. For the remainder of Stottlemyre’s career, a discussion of his accomplishments was often accompanied by the nostalgic remark that he arrived on the team 10 years too late.

In 1965 the Yankees experienced their first losing season since 1925 and fell to the second division for the first time since 1917, but Stottlemyre emerged as one of baseball’s best hurlers. He set the tenor by shutting out the California Angels in his season debut. Remarkably consistent, Stottlemyre paced the AL with 18 complete games in 37 starts, led the league with 291 innings (including consecutive 10-inning affairs), won his 20th game in his final start of the season, and posted an impressive 2.63 ERA. He was named for the first of five times to the AL All-Star squad (he did not pitch) and to The Sporting News All-Star team.

Stottlemyre’s success is often attributed to his sinker, which Yankees coach Jim Hegan compared to that of his former batterymate with the Cleveland Indians, Hall of Famer Bob Lemon. They both threw the sinker overhand, whereas most throw it side-arm or three-quarters because of how difficult a pitch it is to control.12 Said Stottlemyre, “When [the wind] blows in, I may be a bit faster, but my ball straightens out. When the ball blows out, my ball sinks.”13 Cerebral and reflective, Stottlemyre also succeeded because of his ability to adjust over time. Around 1962 he took pitching coach Johnny Sain’s advice and began gripping the ball with the seams instead of across them in order to get a bigger break.14 This change made his fastball as effective as his sinker. “I created some movement with my delivery and the way I held the ball, but mostly it was just natural.”15 Often touted for his good control (2.7 walks per nine innings in his career), Stottlemyre himself admitted, “I couldn’t throw the ball straight if I wanted to.”16

Described as “strangely inconsistent” in 1966, Stottlemyre’s season was a study in contrasts for a team in turmoil.17 The Yankees’ experiment with Johnny Keane, the former Cardinals skipper hired after he beat the Bronx Bombers in the ’64 Series, ended 20 games into the season with the club in last place. He was replaced by Ralph Houk, who could do little to keep the Yankees from finishing in the cellar for the first time since 1912, when the club was known as the Highlanders. One of the team’s few early season standouts, Stottlemyre carved out a sturdy 2.71 ERA through the end of June (despite a 7-8 record) before the bottom the fell out. Excluding a two-inning outing in the All-Star Game in which he yielded one hit and one walk, Stottlemyre’s ERA almost doubled (5.02) for the remainder of the season, and he concluded a frustrating campaign by becoming the first Yankee hurler to lose 20 games (12-20) since Sad Sam Jones in 1925. “I was giving in (to the hitters),” Stottlemyre told Phil Pepe. “Instead of walking them, I came in with a fat pitch and they hit it.”18 His ERA jumped to 3.80 overall and he completed just nine of 35 starts. “I learned a lot through adversity. I got to the point where I almost hated to walk out to the mound,” recalled Stottlemyre later in his career.19

Recognizing that he needed to make adjustments, Stottlemyre dumped his slow curve, which had affected his sinker, in 1967, and honed his rising fastball. The sailing heater “makes batters hesitate about leaning out to hit my slider,” said Stottlemyre.20 The changes paid immediate dividends as Stottlemyre blanked the Washington Senators on two hits on Opening Day and the Boston Red Sox on four hits in his second start. In late April he developed tendinitis in his right shoulder, which required X-ray treatment and caused him to miss two starts. For the rest of his career, Stottlemyre contended with shoulder soreness. In a workmanlike season, the right-hander re-established himself as the Yankees ace, going 15-15 and posting a 2.96 ERA in 255 innings. Even in a pitchers’ era, the Yankees were an especially atrocious offensive team, batting just .225 and scoring an AL-low 522 runs as they finished in ninth place. In 14 of Stottlemyre’s losses, New York scored two runs or fewer (16 total runs).

Stottlemyre reported to camp in 1968 in good spirits following surgery to correct lingering problems with his right foot, which had affected his stamina the previous two seasons, limiting him to just 19 complete games.21 His mood soon turned sour when tendinitis resurfaced in his shoulder and caused him to miss two weeks. Thus, a pattern was established.22 Plagued annually by bouts of shoulder tendinitis, Stottlemyre was eased into spring training for the remainder of his career.

After walking a career-high 3.1 batters per nine innings in 1967, Stottlemyre made yet another adjustment. “I’ve always thrown across my body, but I was throwing more and more across my body and it was affecting my control,” he explained. “I tried to widen my stance at the end of my follow-through and this cut down a lot on my body crossing.”23 Stottlemyre’s walk ratio fell to a career-low 2.1 per nine innings. He fired shutouts in three of his first seven starts, including a three-hitter against the Detroit Tigers at Yankee Stadium on April 26 when Mickey Mantle blasted home run number 521 to tie Ted Williams for fourth place on the all-time list. Named to the All-Star Game for the third time, he faced only one batter, Hank Aaron, whom he struck out in the ninth. The 26-year-old set career career bests in wins (21) and ERA (2.45), finished tied for second in the league in complete games (19) and shutouts (6), and placed third in innings (278⅔) while the Yankees enjoyed their first winning season since 1964. “There is no question that Mel rates with the top five pitchers in baseball,” said skipper Houk.24

People regularly praised Stottlemyre for his character, sportsmanship, and unassuming leadership. “He doesn’t moan when you don’t get him runs,” said Houk, “[or] when they kick ones behind him.”25 Quiet and self-effacing, Stottlemyre rarely sought the spotlight or chewed out his teammates. He was seen as “old school” before the term was common, an embodiment of Yankees style more reflective of the 1940s and 1950s than the mid- to late 1960s and early 1970s. “In the second-division days around the stadium,” wrote beat reporter Jim Ogle, “Stottlemyre is one Yankee who retains the old championship aura and class.”26 Stottlemyre’s outwardly quiet demeanor belied a passion and desire to succeed. Said one-time Yankees backup catcher Bob Schmidt, “He works like a machine, never showing his feelings. Inside he’s thinking and fighting and planning to win.”27

Often described as a country boy, Stottlemyre shunned the media capital and returned to his beloved Washington state to spend the offseasons hunting and fishing, and above all to be with his wife, Jean (Mitchell), whom he married in November 1962. The “big city hasn’t spoiled him,” opined Ogle.28 A consummate teammate, Stottlemyre also had a humorous side and enjoyed joking with his teammates. “I was a quiet prankster,” he once said. “I could get away with a lot of things [because] no one ever suspected.”29

An excellent and agile fielder, the 6-foot-1, 180-pound Stottlemyre might have been considered the best at his position in the AL had Jim Kaat (who won 16 consecutive Gold Gloves from 1962-1977) not been in the league. Stottlemyre led AL pitchers in fielding and assists twice and in putouts three times. Not an automatic out at the plate, Stottlemyre batted .160 (120-for-749), homered seven times, and knocked in 57 runs. Four of those came in a victory over the Red Sox at Yankee Stadium on July 20, 1965, when he became the first hurler since 1910 to hit an inside-the-park grand slam. Said Jim Turner, a baseball lifer and longtime Yankees pitching coach, “[He] would be an outstanding pitcher in any era. He is intelligent, a fine fielder, has three or four big-league pitches, a perfect temperament, and is a great competitor.”30

In 1969 the Yankees had a losing record (80-81) for the fourth time in Stottlemyre’s five full seasons, but the righty was not to blame. In the wake of Mantle’s retirement on March 1, Stottlemyre inherited the Commerce Comet’s mantle of leadership. “There’s no more respected player with the Yankees than Stottlemyre,” wrote Ogle.31 He made a seamless transition to the lowered pitching mound mandated by Major League Baseball to generate more offense following the “Year of the Pitcher.” In his last start of the season, Stottlemyre won his 20th game and finished with 303 innings, the first Yankee to break the 300-inning barrier since Carl Mays in 1921. He set numerous career highs, including starts (39), innings, and complete games (24, to lead the AL). His 2.82 ERA trailed only lefty Fritz Peterson (2.55) among Yankees starters. Tabbed to start the All-Star Game, Stottlemyre was rocked for four hits and three runs (two earned) to get tagged with the loss in one of the few blemishes in an otherwise stellar campaign.

The Yankees made Stottlemyre the highest-paid pitcher in team history in 1970 when they signed the 28-year-old for $70,000.32 He put up typical numbers (37 starts and 271 innings), but was bothered all year by chronic shoulder pain that limited him to a 15-13 record and just 14 complete games. “I was afraid to cut loose because my arm was tight,” he said.33 In his final All-Star appearance, he tossed 1⅔ hitless innings of relief. Led by rookie catcher Thurman Munson and outfielder Bobby Murcer, the Yankees won 93 games but finished well behind the Baltimore Orioles, winners of 108 games.

“We couldn’t sustain our success,” said Stottlemyre in his biography. “CBS owned the ballclub … and the feeling among the players, based on what we knew, was that there was no strong baseball presence in the front office. It was a true corporate ownership.”34 In 1971 the club regressed to 82-80 as offense around the majors plummeted despite the lowered mound. After arguably his worst outing as a big leaguer (seven hits and six runs in one-third of an inning against the Minnesota Twins), Stottlemyre surged, completing six of his final 10 starts of the season. Included were three shutouts (two of them three-hitters), and he forged a stellar 2.05 ERA in 79 innings. “He doesn’t embarrass you,” said teammate Roy White. “He doesn’t overwhelm you. He’s an annoying kind of pitcher. He just gets you out.”35 Stottlemyre led the corps with 16 wins, a 2.87 ERA, 19 complete games, and seven shutouts to anchor a staff that boasted four hurlers (Stottlemyre 269⅔ innings; Peterson 15-13, 274; Stan Bahnsen 14-12, 242; and Steve Kline 12-13, 222⅓) with at least 200 innings, the most since five turned the trick in 1922.36

“The best word to explain the year for me is frustrating,” Stottlemyre told Jim Ogle as the 1972 season, which was marred by the first players’ strike in history, came to a conclusion.37 While the Yankees finished in fourth place in the AL East, Stottlemyre enjoyed stretches when he was either very good or very bad. In May he tossed three shutouts in four starts; fired two more shutouts and tossed 10 scoreless innings for another victory during a two-week period in July; and was on fire in September, posting a 1.67 ERA over 54 innings, but won just twice, both shutouts. However, he struggled in June (4.28 ERA), and in seven starts in August he yielded 33 runs in 40⅔ innings. “That stretch was the worst I ever had,” he said.38 He finished with 14 wins and seven shutouts, but completed only nine games while his ERA (3.22) was higher than the league average. His 18 losses tied for the AL lead in that dubious category, but the Yankees didn’t help him much, scoring two runs or fewer in 16 of those defeats.

In 1973 Stottlemyre split 32 decisions, completed half of his 38 starts and logged 273 innings for the Yankees, who finished in fourth place for the third consecutive year. Newsworthy at the time, Stottlemyre also broke Red Ruffing’s team record by starting his 243rd consecutive game without a relief appearance (and set a then big-league record by starting his 274th game without a start, in 1974) Arguably the season’s most memorable moment came when pitchers Fritz Peterson and Mike Kekich announced during spring training that they were trading lives, including wives, kids, and houses. George Steinbrenner had purchased a majority stake in the Yankees prior to the 1973 season and vowed to make substantial changes to return the team to glory. After a failed and litigious attempt to sign former Oakland A’s manager Dick Williams for the 1974 season, “The Boss” signed Bill Virdon. Under Virdon, the Yankees were one of the surprise teams in baseball in 1974, winning 89 games and occupying first place as late as September 22 in their first pennant race since Stottlemyre’s rookie season, before finishing in second place.

As fate would have it, the stoic pitcher was relegated to a fan for much of the pennant race. After enduring years of regular cortisone shots in his shoulder to numb the pain and make pitching possible, Stottlemyre was diagnosed with a torn rotator cuff after 15 starts in 1974, effectively ending his career at the age of 32. Years before corrective surgery was devised, Stottlemyre rested his shoulder, but continued to pitch on the side, probably damaging his shoulder even more. Not ready to give up, Stottlemyre reported to spring training in 1975, but pain limited him to pitching only batting practice. In late March the Yankees stunned baseball by releasing him. “It seems like a heartless move to cut loose so coldly such a loyal and devoted servant,” decried Phil Pepe.39 “I am not surprised,” said Stottlemyre, “but I am disappointed.”40 In nine full seasons and parts of two others, Stottlemyre compiled a 164-139 record with a 2.97 ERA in 2,661⅓ innings, 40 shutouts, and 152 complete games.

With “bitter memories” about his release, Stottlemyre returned to Washington state and his wife, Jean.41 They had three children — Todd, Mel, and Jason. He operated a sporting-goods store and coached his sons’ youth baseball teams, but recognized that he missed the big leagues. He inaugurated the second phase of his career in baseball when he accepted the expansion Seattle Mariners’ offer to serve as a roving pitching instructor. He resigned in 1981 when his youngest son, Jason, succumbed at the age of 11 to a five-year battle with leukemia. In an ironic twist, Todd was chosen by the Yankees, with whom Stottlemyre had lost all connections, in the 1983 amateur draft. Though he never donned the pinstripes, Todd fashioned a 14-year career, winning 138 games. Mel Jr. was a first-round draft pick by the Houston Astros in 1985, and enjoyed a cup of coffee in the majors with the Kansas City Royals in 1990.

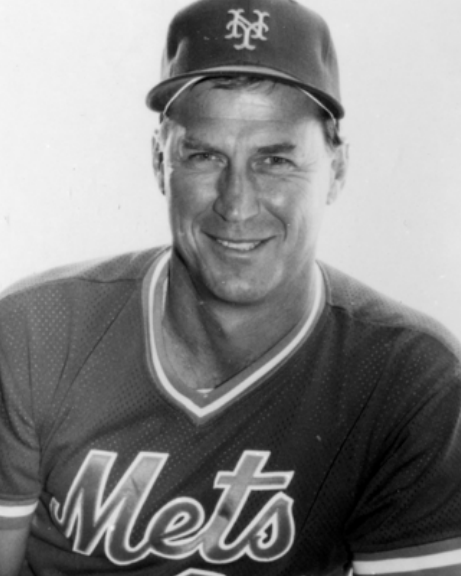

After a three-year hiatus, Stottlemyre returned to the big leagues in 1984 as the pitching coach for the New York Mets. From 1984 to 1990, the Mets averaged more than 95 wins per season, but finished in first place just twice, in 1986 and 1988. These teams were led by catcher Gary Carter, third baseman Howard Johnson, and volatile slugger Darryl Strawberry; however, the face of the franchise was the pitching staff and especially Dwight “Doc” Gooden. Widely considered one of the best teams in baseball history, the 1986 squad won 108 games and defeated the Boston Red Sox in seven games in the World Series. The starting rotation was led by Gooden (17-6, 2.84 ERA), Ron Darling (15-6, 2.81), Bob Ojeda (18-5, 2.57), and Sid Fernandez (16-6, 3.52), and each logged in excess of 200 innings. Those successful years stand in stark contrast to the period from 1991-1996 when injuries, age, free agency, and rumors of widespread drug use among players led to six consecutive losing seasons that reached their nadir in 1993 (103 losses and Stottlemyre’s dismissal).

After a three-year hiatus, Stottlemyre returned to the big leagues in 1984 as the pitching coach for the New York Mets. From 1984 to 1990, the Mets averaged more than 95 wins per season, but finished in first place just twice, in 1986 and 1988. These teams were led by catcher Gary Carter, third baseman Howard Johnson, and volatile slugger Darryl Strawberry; however, the face of the franchise was the pitching staff and especially Dwight “Doc” Gooden. Widely considered one of the best teams in baseball history, the 1986 squad won 108 games and defeated the Boston Red Sox in seven games in the World Series. The starting rotation was led by Gooden (17-6, 2.84 ERA), Ron Darling (15-6, 2.81), Bob Ojeda (18-5, 2.57), and Sid Fernandez (16-6, 3.52), and each logged in excess of 200 innings. Those successful years stand in stark contrast to the period from 1991-1996 when injuries, age, free agency, and rumors of widespread drug use among players led to six consecutive losing seasons that reached their nadir in 1993 (103 losses and Stottlemyre’s dismissal).

After a two-year stint as the pitching coach for the Houston Astros, Stottlemyre reconciled with Steinbrenner and accepted his offer to become the club’s pitching coach for new manager Joe Torre. For the next 10 seasons (1996-2005), Stottlemyre enjoyed the fruits of unimaginable success, including nine first-place finishes, 10 playoff appearances, six pennants, and four World Series championships. In 1999 Stottlemyre was diagnosed with multiple myeloma, a cancer of plasma cells, and ultimately recovered after intensive chemotherapy. In the wake of the Yankees’ collapse in the 2001 World Series, Stottlemyre’s relationship with Steinbrenner became strained as the owner privately and publicly second-guessed his pitching coach. “Baseball was my life,” said Stottlemyre, trying to explain why he didn’t walk away.42 That changed in 2005, when the stress of the situation had finally begun to take a toll on Stottlemyre’s health, and he retired at the end of the season.

Retirement didn’t last long. After a one-year break, he served as a special-assignment instructor for the Arizona Diamondbacks in 2007. The next season he was back in a big-league dugout when he joined the Seattle Mariners’ coaching staff. Approaching his 69th birthday, Stottlemyre retired after the 2008 season. A quiet, unassuming player and a dedicated, well respected coach, Stottlemyre spent almost 50 years in Organized Baseball.

He died on January 13, 2019 at the age of 77.

Sources

In addition to the sources listed in the notes, the author consulted:

Baseball-Reference.com.

Retrosheet.org.

SABR.org.

Mel Stottlemyre’s player file, National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York.

Notes

1 Phil Pepe, “Stottlemyre’s Courage Showed In His Son,” New York Daily News, March 16, 1981.

2 Mel Stottlemyre with John Harper, Pride and Pinstripes (New York: Harper, 2007), 16.

3 A member of the NCAA Hall of Fame, Brayton coached at Yakima State Junior College from 1951 to 1961, compiling a 251-68 record, including 10 championships in 11 seasons; he piloted the Washington State Cougars for 33 years (1962-1994) and compiled a 1162-523-8 record.

4 The Sporting News, October 24, 1964: 9.

5 The Sporting News, May 9, 1962: 41; and August 11, 1962: 42.

6 The Sporting News, August 11, 1962: 42.

7 The Sporting News, October 24, 1964: 9.

8 The Sporting News, August 29, 1964: 21.

9 Sy Berwick, “Stottlemyre Had No Choice, Only the Yanks Offered a Contract.” Dayton (Ohio) Daily News, October 9, 1964: 9.

10 The Sporting News, October 31, 1964: 21.

11 Robert W. Cohen, The Lean Years of the Yankees, 1965-1974 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2004).

12 The Sporting News, August 29, 1964: 21.

13 The Sporting News, July 24, 1965: 9.

14 The Sporting News, May 1, 1965: 10.

15 Stottlemyre, 24.

16 Ibid.

17 The Sporting News, August 6, 1966: 15.

18 The Sporting News, September 18, 1971: 5.

19 Ibid.

20 The Sporting News, April 29, 1967: 19.

21 The Sporting News, June 15, 1968: 18.

22 The Sporting News, April 13, 1968: 37.

23 The Sporting News, April 27, 1968: 20.

24 The Sporting News, August 24, 1968: 17.

25 Larry Fox, “Houk Rates Stottlemyre in Top Five,” Daily News (New York), July 26, 1968.

26 The Sporting News, June 15, 1968: 18.

27 The Sporting News, December 5, 1964: 5.

28 The Sporting News, May 3, 1969: 3.

29 Ross Forman, “Mel Stottlemyre: From pitching star to pitching coach,” Sports Collectors Digest, August 7, 1992: 181.

30 The Sporting News, May 3, 1969: 3.

31 Ibid.

32 The Sporting News, February 21, 1970: 21.

33 The Sporting News, June 19, 1971: 19.

34 Stottlemyre, 48.

35 Neil Offen, “… Then Along Came Stottlemyre,” New York Post, May 13, 1971: 6C.

36 In 1922 five Yankees pitchers hurlers hurled 1,320⅔ of the team’s 1,393⅔ innings: Bob Shawkey (20-12, 299⅔); Waite Hoyt (19-12, 265), Sad Sam Jones (13-13, 260), Bullet Joe Bush (26-7, 255⅓), and Carl Mays (13-14, 240).

37 The Sporting News, October 7, 1972: 8.

38 Ibid.

39 The Sporting News.

40 United Press International, “Stottlemyre Not Surprised,” Beckley (West Virginia) Post-Herald and Register, March 31, 1975: 31.

41 Forman: 190.

42 Stottlemyre, 23.

Full Name

Melvin Leon Stottlemyre

Born

November 13, 1941 at Hazleton, MO (USA)

Died

January 13, 2019 at Seattle, WA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.