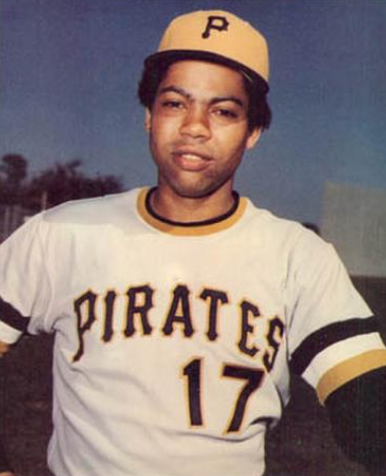

Dock Ellis

One of the best pitchers of the 1970s, Dock Ellis feared success nearly as much as he feared failure. He both angered and amused. His antics cut across racial and cultural lines, as he challenged old prejudices and “normal” ways of doing things. Ellis pitched a no-hitter in 1970 and the next year led the Pirates with 19 victories, started the All-Star Game for the National League, and won the World Series. He served as player representative for the Pirates, Yankees, and Rangers, and even got one vote for the Hall of Fame, yet claims he never pitched a game in the major leagues without the assistance of alcohol or drugs.1

One of the best pitchers of the 1970s, Dock Ellis feared success nearly as much as he feared failure. He both angered and amused. His antics cut across racial and cultural lines, as he challenged old prejudices and “normal” ways of doing things. Ellis pitched a no-hitter in 1970 and the next year led the Pirates with 19 victories, started the All-Star Game for the National League, and won the World Series. He served as player representative for the Pirates, Yankees, and Rangers, and even got one vote for the Hall of Fame, yet claims he never pitched a game in the major leagues without the assistance of alcohol or drugs.1

Known as Peanut, then later simply “The Nut,” Dock Phillip Ellis Jr., was born on March 11, 1945, in Los Angeles. His father, known as Big Dock, worked in a post office and as a longshoreman, then went to school to learn shoe repair. His wife, Naomi, assisted him when they opened a shoe-repair shop and a dry-cleaner business.

Dock attended the predominantly white Gardena (California) High School in hopes of finding a better education but found a good dose of racial prejudice. To avoid suspension when he got caught drinking and smoking marijuana at school, he agreed to go out for baseball. But he found racial resistance there as well. He excelled at basketball, however, as the only black person on the team.

Big Dock died when Dock was 18, and Dock decided to focus solely on baseball. Playing mostly in the infield, he became a pitcher when one day he threw the ball from the outfield fence all the way over the backstop. A tall, lanky right-hander at 6-feet-3 and 195 pounds, he batted both ways and threw so hard his friends would stop playing catch with him.2

Ellis attended Los Angeles Harbor College in Wilmington, California, but spent most of his time playing baseball in Watts for former Negro Leagues pitcher Chet Brewer. Brewer scouted for the Pirates and tutored several future major leaguers, including Bob Watson, Bobby Tolan, and Enos Cabell. Fielding several offers, Ellis always wanted to sign with Pittsburgh, as he finally did in 1964, but saw his signing bonus reduced from $60,000 to $2,500 after his arrest for stealing a car.3

When Ellis started at the Pirates’ Class A team in Batavia, New York, he felt extreme pressure to succeed and became steadily involved in alcohol and drugs. Homesick and lonely, he went to a bar with teammates and ordered a beer, hoping to pass as 21. When the waitress informed him that the drinking age in New York was 19, he said, “Okay, take the beer back, and bring me some vodka stingers.”4

Despite his fears, Ellis excelled, but he soon became addicted to stimulants like Benzedrine (bennies) and Dexamyl (greenies). “I was into the speed … because of the expectations … to hurry up and get to the big leagues,” Ellis recounted. “I had a no-miss tag on me. ‘It’s impossible for this kid not to get to the big leagues.’ That’s a lot of stress.”5

In 1965 Dock married his first wife, Paula Hartsfield, an accomplished athlete and the first black homecoming queen at George Washington High School They were 20 and 17, respectively. They had one daughter, Shangaleza, in 1969.

Ellis had an overall won-lost record of 41-31 during his first four minor-league seasons through 1967. On the brink of making the Pirates in March 1968. he felt emboldened: “I held out this spring because … I never did get a bonus, and I thought I was entitled to more money.”6

He finally accepted his contract and joined the Columbus Jets, the Pirates’ Triple-A affiliate. He made his major-league debut on June 18 at Pittsburgh in relief against the Los Angeles Dodgers, and got his first win, pitching the 10th inning and allowing one hit. Ellis made and won his first start on July 31 in the second game of a twi-night doubleheader at Cincinnati’s Crosley Field, and finished the year in the starting rotation. In 1969 Ellis continued as a starting pitcher. Although he lost 17 games, he completed over 200 innings with a 3.58 earned-run average.

On Wednesday, June 10, 1970, Pittsburgh lost a day game in San Francisco and flew to San Diego for four games. Ellis obtained permission to drive home Thursday, an offday, and planned to return Friday to pitch the first game of a doubleheader. He said he took LSD on the way and timed it to kick in about the time he reached Los Angeles. He stayed with friends and continued with vodka and more acid, then lost track of the days.

A friend’s girlfriend woke him up at 2:00 P.M., saying “Dock, you have to pitch today in San Diego!”

“I don’t pitch until Friday,” he replied.

“It is Friday!” she said.

“O wow. What happened to yesterday?” said the confused pitcher.7

Ellis caught a flight at 3:00 P.M. and arrived at the misty, drizzly, half-empty ballpark at 4:30 for the 6:05 game. He remembered having a sense of euphoria, with the ball feeling sometimes big like a balloon, sometimes small like a golf ball. He saw a comet tail on his pitches and Richard Nixon umpiring behind the plate. He could not see the hitters well enough except to tell whether they were on the right or left side of the plate. Catcher Jerry May had his fingers wrapped with reflective tape to help.8

Rookie Dave Cash sat next to Ellis in the dugout and from the fifth inning kept reminding him that he had a “no-no” going. Nine innings, eight walks, and one hit batsman later, the weak-hitting Padres lost, 2-0, without producing a hit. Pirates second baseman Bill Mazeroski saved the no-hitter for the first out in the bottom of the seventh inning with a “fantastic backhanded grab” of a line drive from pinch-hitter Ramon Webster. “I didn’t think I had a chance for it,” said Mazeroski after the game. Ellis knew otherwise: “When Maz dove, I knew he’d grab it.”9

Ellis insisted that he did not intend to take LSD before pitching. He lost track of time. Yet he did admit that he worried about how he would be able to pitch. He knew the effects of LSD would not wear off before the game, so he took some speed, “because it was a habit. It was natural to take stuff, forgetting that I had taken the acid.”10

Ellis went on to pitch three more shutouts in 1970, then developed a sore arm in mid-August and missed over a month. He still led Pirates starting pitchers with 13 wins, as the team won its division but was swept in three games of the best-of-five NLCS by the Cincinnati Reds.

Still complaining about arm trouble in 1971, Ellis started the season strong. His record of 14 wins against only three losses with a 2.11 ERA by July 6 earned him his first and only All-Star Game selection. When he learned that pitcher Vida Blue would start the game for the American League, he challenged the racial preferences in baseball: “They’ll never start one ‘brother’ against another ‘brother.’” The manager of the National League All-Stars, Sparky Anderson, said he picked Ellis to start because of his excellent numbers and the fact that he had six days’ rest.11 Ellis claimed that he had intentionally used a form of reverse psychology to ensure the outcome. “I said they wouldn’t do it, so they had to.”12

Ellis fared well through the first two innings of the game, allowing just a single. Then Luis Aparicio led off the third inning with a single, and Reggie Jackson, pinch-hitting for Blue, blasted Ellis’s pitch off the light tower in right-center field at Tiger Stadium. With two outs, Frank Robinson added another two-run homer. Norm Cash struck out to end Ellis’s All-Star career. The AL went on to win, 6-4, hanging the loss on Ellis.

Later that season the Pirates made history on September 1 against the Philadelphia Phillies by starting an all-black lineup, using a combination of American and Latin players, with Ellis as the starting pitcher.

Although Ellis finished the rest of the season with a mediocre five wins and six losses and a 4.50 ERA, the Bucs went on to beat the San Francisco Giants three games to one in the NLCS. They won the World Series, defeating the Baltimore Orioles in seven games.

While in San Francisco for the first two games of the League Championship Series, Ellis complained about his bed being too short in the team hotel, the Jack Tar. He insisted on a suite, volunteering to pay the extra, but there were none available. Ellis checked out and moved to the Hilton. He also complained during the World Series in Baltimore about the Lord Baltimore Hotel. He got a different room, then finally moved to another spot with two rooms adjoining. He called the Pittsburgh “Establishment” cheap and bush league.13 In Ellis’s only appearance in the World Series, the Baltimore fans booed him loudly and waved handkerchiefs at him when he left the field during the third inning of the first game.14 Many thought the Pirates would surely trade him, with his sore arm and loud mouth, but he stayed with Pittsburgh the next four seasons.

Ellis started on Opening Day for the Pirates in 1972, but still felt some arm soreness and even threatened to retire by age 30. He almost found himself sitting out more time than expected after an encounter with a security officer at Riverfront Stadium in Cincinnati. When Ellis arrived at the stadium together with Willie Stargell and Rennie Stennett on May 5, the guard, David Hatter, asked them all for identification. When Ellis flashed his world championship ring, Hatter interpreted his raising his fist, along with his “vile language,” as a confrontation, and sprayed the hurler with Mace, arrested him, and charged him with disorderly conduct.15

Ellis sued the Reds, and the Cincinnati team dropped all charges before the trial. Ellis and the Reds wrote Reds apologies to each other.

Pittsburgh general manager Joe Brown admitted that Ellis had no identification card at the time because the team had never issued any. Within three days of the incident, the Pirates issued pink identification cards to all the players, with their pictures on the back.16

In 1972 Ellis pitched in only 25 games, all starting assignments. With all the controversy and arm concerns, he nonetheless had a very good year, with 15 wins, 7 losses, and a 2.70 ERA. He posted his best WHIP (1.157) since his rookie season in 1968.

The Pirates won the NL Eastern Division for a third consecutive season, but lost the NLCS to the Reds in five games via dramatic walk-off fashion on a ninth-inning wild pitch. Ellis started the fourth game with the Pirates up two games to one and looking to clinch another pennant, but he was touched for three unearned runs on three Pittsburgh errors in five innings, and took the loss.

Ellis formed a very close relationship with Roberto Clemente. They roomed together when Ellis first got to the Pirates, and Roberto helped the kid from “the Neighborhood” make some adjustments to life in the big-time baseball arena. Clemente’s tragic death in late 1972 shocked and traumatized Ellis. He went on a violent rampage in his house, displacing his anger and grief on his wife, Paula. They soon divorced.

Ellis started the 1973 pretty smoothly, until a picture circulated through the newspapers showing him in the bullpen before a game in August wearing hair curlers under an oversized cap. He wore them only during pregame warm-ups, but Pirates manager Bill Virdon passed word to him to stop wearing them.17 Ellis accused Commissioner Bowie Kuhn of sending the edict, hiding behind Virdon. “There are many black men who wear curlers to help their hair,” he said. “Baseball is getting behind the times again.”18 Ellis admitted later to biographer Donald Hall that he never wore curlers around the house, only before games. “That’s when I was throwing spitballs. When I had the curlers, my hair would be straight. Down the back. On the ends would be nothing but balls of sweat.”19

Again, Ellis developed arm trouble toward the end of the season. He missed the first three weeks of September and feared missing a pay raise the next year, saying, “This is going to cost me money now.”20 He had knee surgery in October to repair injuries from a fall when he was 11 years old. His doctors hoped that the surgery could actually help some of his arm problems. Despite the health holdups, Ellis had been one of the sturdiest pitchers on the Pirates staff, both winning and losing more games (59-40) than any other Pittsburgh hurler from 1970 through 1973.21

One day in 1974, the intimidation that Ellis felt building up from Cincinnati’s dominance drove him to seek his own form of revenge against them. His anger dated back to losing the 1972 playoffs to the Reds. “All I heard was their players talking about how the Pirates were dumb players, and that’s why they beat us.”22 On May 1 Ellis took the mound at Three Rivers Stadium in Pittsburgh to face Pete Rose, the first player to bat. He hit Rose, then Joe Morgan, then Dan Driessen, loading the bases. He tried to hit the fourth batter, Tony Perez, but Perez dodged the pitches and took a walk, forcing Rose home from third. Pittsburgh manager Danny Murtaugh had seen enough and pulled Ellis out. No other pitcher had hit three consecutive batters since a hundred years before, when Emerson “Pink” Hawley of the 1894 St. Louis Browns hit three in the first inning.23

Ellis had a reasonably good year in 1974, with 12 victories and a 3.16 ERA, yet again did not finish September because of arm trouble. The Pirates finished first in the NL East Division, but Ellis did not pitch in their three-games-to-one NLCS loss to the Los Angeles Dodgers.

Ellis enjoyed doing imitations in the clubhouse. He would do other players and umpires, but especially loved doing Muhammad Ali. One day in 1975 the Champ himself wandered into the Pirates clubhouse. Ellis showed off his quick feet and his quick mouth. Then Ali thumped him with a strong left jab to Dock’s chest, throwing him back almost off his feet. Nevertheless, Ellis still fashioned himself “the Muhammad Ali of baseball.”24

Late in the 1975 season Ellis refused an assignment to the bullpen. When he announced that he would speak to the team, everyone expected an apology. Instead, they got a rant against manager Danny Murtaugh, for which Ellis earned a 30-day suspension. Some players said Ellis tried to speak constructively, but others heard his words very differently. With the help of lawyer/agent Tom Reich, who had helped him during the Macing incident, Ellis was reinstated retroactively after 14 days. He did not lose any pay but still suffered a hefty fine. Ellis reluctantly accepted the bullpen assignment, but the ever-present trade rumors began to sound a lot more realistic during the offseason.25

The trade finally came — on December 11, 1975, to the New York Yankees. The very unbalanced transaction sent pitcher Ken Brett and second baseman Willie Randolph to the Yankees for pitcher Doc Medich, with Ellis’s name added as a “throw-in.”

As he left Pittsburgh, Ellis professed his love for the Pirates. “When the Pirates first signed me in 1964, I was wild. I was called a militant, although I don’t think it was so. Joe Brown tried to understand me, and he did. So did the people who own the Pirates — the Galbreaths.” Ellis said he really wanted to play for Billy Martin and the Yankees, and promised to focus totally on baseball in 1976, but he added, “I’ll always be a Pittsburgher. I like the people there. I like the Pirates, too.”26

Ellis started very strong in New York in 1976. By mid-July he had an 11-4 record, with five complete games and a 3.14 ERA. He pitched well throughout the season and posted 17 victories, the second-highest in his career, while topping 200 innings for the first time since 1971.

A beanball battle raged between the Yankees and the Orioles that season. On July 27 Ellis hit Baltimore’s Reggie Jackson on the side of the face, forcing the slugger to go to the hospital for x-rays and miss a few games until the swelling went down. Jackson had hit six home runs in six games. Later in the game, Orioles pitcher Jim Palmer obviously retaliated by hitting Mickey Rivers.27

Many remembered Jackson’s towering home run off Ellis in the 1971 All-Star Game, but Ellis insisted that the July 27 incident arose from Jackson’s taunting from the dugout and in the on-deck circle immediately before his at-bat.

Ellis started and won Game Three of the ALCS against the Kansas City Royals, then lost his start in Game Three at Yankee Stadium in the World Series against the Reds, who took four straight from the Yankees. Ellis received recognition for his standout season, as The Sporting News named him and Tommy John of the Dodgers the Comeback Players of the Year for 1976.

Peaceful times did not last long in New York for Ellis as he expected better compensation for his work. Reminiscing about the trade that brought him to the Yankees, he said, “The Yankees got me at a fire sale, and now they don’t want to give me any money.”28 He also had words of advice for Yankees owner George Steinbrenner. “I think he should stay up in his office, push his buttons, count his money, and stay out of the locker room.”29

The Yankees now saw Ellis as expendable. In a move labeled as a trade of “headaches,” they sent him to the Oakland Athletics on April 27, 1977, along with outfielder Larry Murray and infielder Marty Perez, for pitcher Mike Torrez. “It’s not the idea that I’m happy to be leaving the Yankee organization. I wasn’t being paid, so I have to leave,” reflected Ellis. He said joining the A’s team full of rookies “makes me feel young again. Hopefully, I will pitch like I’m younger.”30

Ellis had a very rough beginning with Oakland, with no wins and three losses in his first four starts, and a 23.48 ERA. His next three went much better, with an ERA of 3.93, but he won only one against two losses. Three days before his turnaround he shaved his head, a major shift from his usual style and a marked contrast from his curlers days.31

While in Oakland Ellis pulled what he later called the craziest thing he ever did. “They wanted me to keep charts. I said, ‘Bleep the charts,’ and set ’em on fire. They thought the clubhouse in Cleveland was on fire. The alarm went off. The automatic sprinklers started.”32

Ellis’s Oakland days lasted only until June 15, when the Texas Rangers purchased his contract for $275,000. But before he left Oakland, he had played for his third manager of the season. Charlie Finley, owner of the Athletics, changed skippers on June 10 when he surprisingly replaced Jack McKeon with Bobby Winkles.33

Rangers owner Brad Corbett received a lot of criticism, from fans and media alike, for signing Ellis. “All I can tell you that he’s done a magnificent job for us,” reported Corbett. “Dock Ellis got a bad rap. I love him. He’s fair. He calls it the way he sees it.”34

In July 1977 Dock married Austine Washington. They had one son, Dock Phillip Ellis III, or Trey.

The Rangers also went through a series of managerial shifts in 1977, resulting in Ellis playing for seven skippers during the season, including Frank Lucchesi, Eddie Stanky (one game), Connie Ryan (six games), and Billy Hunter in Texas. His season turned out mildly successful, as he pitched over 200 innings again. He bounced back from the poor showings in Oakland to finish with 10 wins and 6 losses for the Rangers, and a 2.90 ERA.

Once again, as in Pittsburgh and New York, Ellis served as player representative with the Rangers. His outspokenness came out again during the 1978 season. Manager Billy Hunter prohibited players from drinking at the hotel bar and banned mixed drinks on all flights. During a confrontation about the liquor rules with Ellis on the team bus, Hunter told him to sit down and shut up. Then Hunter decided to drop all alcohol from the flights. Enraged, Ellis resigned as player representative, complaining not only about the unreasonable rules, but also about feeling belittled in front of the team. “My father as the last man who told me to [sit down and shut up]. And as far as I’m concerned, nobody else can.”35

Fans and media again called for a trade, but owner Corbett sided with his player over his manager. Hunter turned down a five-year contract extension in midseason, and Corbett fired him with one day left in the season.

Ellis started 1979 with the Rangers, but did not pitch well. On June 15 Corbett relented and traded him to the New York Mets for pitchers Mike Bruhert and Bob Myrick. In 27 games for the Rangers and Mets, Ellis had a 4-12 record and an ERA over 6.00. On September 21 Pittsburgh purchased his contract, and Ellis got his wish to “come back and die as a Pirate.”36 He started one game and pitched two in relief during the last week of the season.

Pittsburgh released Ellis to free agency on November 1. Once again he flew into a rage at home, devastated that the Pirates had let him go. He had focused his whole life, since his teen years, on pitching a baseball. He traumatized his wife, Austine, so much one day at home that when she could get out of the house, she went to a hospital and never got back with Ellis again.

Corbett had promised Ellis a job after baseball, and Ellis traveled the world doing “soft PR” at $50,000 a year promoting his former owner’s plastic-pipe company.37

In the fall of 1980, realizing he had a problem, Ellis called former major leaguer Don Newcombe, who he knew worked with other addicts. Dock called his sister Sandra from the airport and asked her to bring a bottle of vodka. “It’s going to be my very last,” he said.38 Newcombe helped Dock get into The Meadows, a substance-abuse clinic in Wickenburg, Arizona, where he stayed 45 days — two weeks longer than insurance allowed, too terrified to leave until he felt ready to cope.

Ellis dedicated much of the rest of his life to helping fellow addicts find a path to recovery. He actually started this work during his playing days when he visited inmates in Pittsburgh area prisons. His own conversion experience drove his passion to work with others.39 He wanted to “go to where they’re at,” to meet them in the clubhouses and in the bars. “By the time they come for help, they’re already locked up and in trouble with their families.”40

Dock married a third time, to Jacquelyn, in 1985, then soon divorced, and shortly thereafter he married Hjordis, who was with him until he died in 2008.

Dock’s son Trey remembered the sense of calling that his father felt, “that feeling he got knowing he was changing somebody’s life.”41 Ellis never forgot his own struggles. “Continuous recovery! I’ll be recovering until I die!”42

Ellis was diagnosed with cirrhosis of the liver in 2007, and hoped for a liver transplant. With no insurance, his family relied heavily on friends from his baseball career to help pay bills. Heart damage precluded any transplant, and he died on December 19, 2008, at the age of 63.

Around the time of the 1971 All-Star Game, Ellis received what he regarded as perhaps his most prized possession: a handwritten letter from Jackie Robinson. In it Jackie wrote: “Try to get more players to understand your view, and you will find great support. You have made a real contribution.”43

Possibly the most underrated, unpopular, and misunderstood player ever, Dock Ellis redefined “success” as something other than putting up impressive numbers in the major leagues. He pioneered a path across racial and cultural divides, and found a way not only to live beyond his fears but also to walk alongside others who struggled as he did.

Last Revised: April 12, 2023 (zp)

Notes

1 Jeff Radice, director and producer, No No: A Dockumentary. 2014.

2 Ibid.

3 Keven McAlester, “High Times,” Houston Press, June 23, 2005.

4 Jerry Crowe, “Dock Ellis: The Man Who Pitched a No-Hitter While Under the Influence of LSD Has Found a New Delivery: He Coordinates a Substance-Abuse Rehabilitation Program: Ellis: ‘I Couldn’t Pitch Without Pills,’” Los Angeles Times, June 30, 1985.

5 Ibid.

6 Les Biederman, “Blass Blossoms; Ellis Could Be Next to Thrive,” The Sporting News, September 11, 1968.

7 Radice.

8 ESPN.com, “OTL: The Long, Strange Trip of Dock Ellis,” ESPN.go.com.

9 Charley Feeney, “Maz’ Dive Buoys Dock in No-No Against Padres,” The Sporting News, June 27, 1970.

10 Crowe.

11 “Pipeline Full of Chit-Chat,” The Sporting News, July 31, 1971.

12 Donald Hall with Dock Ellis, In the Country of Baseball (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1989), 175.

13 Charley Feeney, “Bucs ‘Stuck’ with Ellis, Big Winner, Big Yelper,” The Sporting News, October 23, 1971.

14 Lowell Reidenbaugh, “Orioles Find Way Back With McNally,” The Sporting News, October 23, 1971.

15 Charley Feeney, “Drydock Beckons Bucs’ Storm-Tossed Ellis,” The Sporting News, May 20, 1972.

16 “Dock Gets Identity Card,” The Sporting News, May 27, 1972.

17 Hall, 215.

18 Charley Feeney, “Even Hair Curlers Rear Ugly Head in Bucs’ Domestic Life,” The Sporting News, September 1, 1973.

19 Hall, 217.

20 “Pirate Ellis in Dry Dock Again,” The Sporting News, September 22, 1973.

21 Charley Feeney, “Bucs’ Moody Ellis Happy — Knee Sound after Surgery,” The Sporting News, March 15, 1974.

22 Crowe.

23 “N.L. Flashes — Dock Makes History,” The Sporting News, May 18, 1974.

24 Radice.

25 Charley Feeney, “Apologetic Dock Earns Return to Bucs,” The Sporting News, September 13, 1975.

26 Charley Feeney, “Dock Dons Walking Shoes for Pirate Exodus,” The Sporting News, December 20, 1975.

27 Jim Henneman, “Oriole Feathers Fly in Duster Fight,” The Sporting News, August 14, 1976.

28 Dick Young, “Young Ideas,” The Sporting News, April 16, 1977.

29 “Insiders Say,” The Sporting News, April 30, 1977.

30 Tom Weir, “Trader Finley Swaps Headaches, Torrez for Ellis,” The Sporting News, May 14, 1977.

31 Tom Weir, “Page Injury Dims One of A’s Few Bright Spots,” The Sporting News, June 18, 1977.

32 Crowe.

33 “Winkles Take Over as A’s Skipper; McKeon Gets Axe,” Gadsden (Alabama) Times, June 11, 1977.

34 Randy Galloway, “Betrayed Corbett Ready to Cash Ranger Chips,” The Sporting News, July 23, 1977.

35 Randy Galloway, “Dock Protesting Dry Runs, Leaps Overboard,” The Sporting News, June 17, 1978.

36 Radice.

37 Hall, 328.

38 Radice.

39 Hall, 336.

40 Radice.

41 “OTL: The Long, Strange Trip of Dock Ellis,” ESPN.com, August 24, 2012.

42 Hall, 336

43 Radice.

Full Name

Dock Phillip Ellis

Born

March 11, 1945 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

Died

December 19, 2008 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.