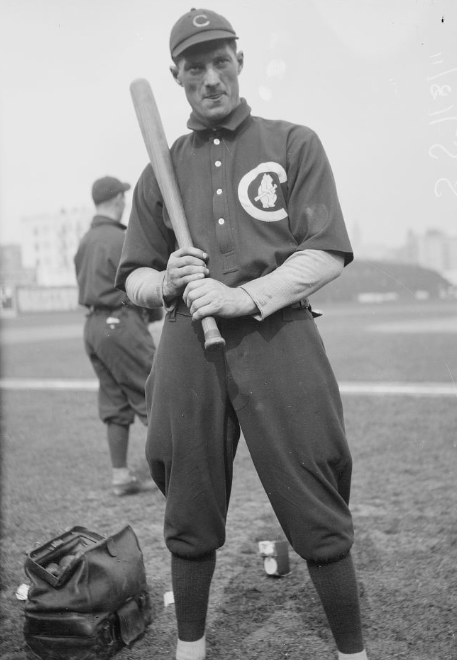

Heinie Zimmerman

A versatile fielder who could play second, third, or short, Heinie Zimmerman rose to prominence with the Chicago Cubs during the early teens as a lovable eccentric whose aggressive batting style won the loyalty of fans and the respect of opposing pitchers. But despite winning the National League’s Triple Crown in 1912, the lifetime .295 hitter never fulfilled his immense potential, instead becoming one of the Deadball Era’s best examples of wasted talent. “Zimmerman’s disposition has not always been fortunate and his all round record hasn’t been quite what it should have been,” wrote F.C. Lane in 1917. “But there is no possible doubt that he is one of the greatest natural ball players who ever wore a uniform.” By the end of the decade, the man who had once come within an eyelash of the Triple Crown found himself driven from the game in disgrace.

A versatile fielder who could play second, third, or short, Heinie Zimmerman rose to prominence with the Chicago Cubs during the early teens as a lovable eccentric whose aggressive batting style won the loyalty of fans and the respect of opposing pitchers. But despite winning the National League’s Triple Crown in 1912, the lifetime .295 hitter never fulfilled his immense potential, instead becoming one of the Deadball Era’s best examples of wasted talent. “Zimmerman’s disposition has not always been fortunate and his all round record hasn’t been quite what it should have been,” wrote F.C. Lane in 1917. “But there is no possible doubt that he is one of the greatest natural ball players who ever wore a uniform.” By the end of the decade, the man who had once come within an eyelash of the Triple Crown found himself driven from the game in disgrace.

Henry Zimmerman was born February 9, 1887, in the Bronx, New York, the ninth of 12 children. His father, Rudolph, a German immigrant who had arrived in the United States in 1860, struggled to support his large family as a traveling salesman of imported furs. Several of his children sacrificed their education to earn more money for the family, including Henry. “When I saw what a hard time the old man was having, I decided to get a job that was a money maker,” he recalled. At age 14, Henry put away his schoolbooks and took up work as a plumber’s apprentice. Though he later claimed to have received all the schooling he needed, others would have disagreed. Sportswriter Warren Brown described Henry as a man who “played his baseball by ear mostly” and “was no mental giant.” Stories of Zimmerman’s stupidity abound, and over time he developed a reputation for dim-wittedness that was unsurpassed, even among ballplayers.

Zimmerman first honed his baseball skills on the ultra-competitive sandlots of New York City. First at a park on the corner of 163rd Street and Southern Boulevard, and later across the Hudson River in Red Bank, New Jersey, Henry established himself as one of the finest semipro players in the metro area. By 1905 he was earning $20 catching and pitching for semipro teams on weekends, which must have seemed like a king’s ransom compared to the $2 per day he took home for fixing leaky faucets in the Bronx. In 1906 Zimmerman signed on as a second baseman for Wilkes-Barre of the New York State League. The Chicago Cubs purchased him for $2,000 in the midst of his second season in Wilkes-Barre.

Only 20 years old when he arrived in the major leagues in August 1907, Zimmerman stood 5′ 11″ and weighed 176 lbs., about average for his day. With an awkward, loping gait and a perpetual sneer plastered across his face, “even Franklin P. Adams would have had trouble reducing him to poetry in motion,” Brown remarked. But the boy could hit. Blessed with exceptionally strong hands and forearms, the right-handed Zimmerman was one of the most aggressive hitters of the Deadball Era, known for swinging at pitches well out of the strike zone and lining them for base hits.

Initially Zimmerman saw little playing time, as the Cubs already featured one of the strongest infields in baseball with Frank Chance, Johnny Evers, Joe Tinker, and Harry Steinfeldt. It wasn’t until Evers went down with an ankle injury late in the 1910 season that Zimmerman had his first real opportunity in Chicago, starting every game of that year’s World’s Series.

Injuries kept Evers on the sidelines for most of 1911, as well, and Zimmerman responded with his first standout season. His .307 batting average and .462 slugging percentage both ranked among the top ten in the National League, but his shaky defense infuriated Manager Chance. When Zimmerman muffed two chances in the early innings of an August 7 game against Boston, Chance pulled him from the field and briefly suspended him for “indifferent fielding.” Zimmerman was quickly becoming one of the most potent offensive weapons in the game, a rare middle infielder who could hit for both power and average, yet going into the 1912 season his status as an everyday player in Chance’s lineup was anything but secure.

All that changed on February 1, 1912, when the Cubs regular third baseman, Jimmy Doyle, died suddenly from appendicitis. As a result of the tragedy, Zimmerman moved from Chance’s doghouse to the hot corner, where he put together one of the best seasons by any player of the Deadball Era. That year he led the NL in the Triple Crown stats of batting average (.372), home runs (14), and RBIs (104), along with slugging percentage (.571), hits (207), doubles (41), and total bases (318).

Following Zimmerman’s death in 1969, his RBI total in 1912 became a matter of dispute after The Baseball Encyclopedia (frequently referred to as “Big Mac”) credited him with just 99 RBIs, in third place behind Honus Wagner‘s 102 RBIs and Bill Sweeney‘s 100. For decades afterward, Zimmerman was not listed among the major-league Triple Crown winners in most reference sources. However, exhaustive research published in 2015 by SABR member Herm Krabbenhoft concluded that Zimmerman’s RBI total did lead the National League and he should correctly be awarded the Triple Crown. Many reference sources like Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet have updated their league leader totals as a result. (Click here to read Krabbenhoft’s article at SABR.org.)

Some thought Zimmerman was just the beneficiary of good luck. Teammate Cy Williams later told F.C. Lane that “he was as good a hitter that year as I ever saw. And what was he doing? He was swinging at balls a foot over his head and driving them safe. You can get away with murder when the luck is with you.” But Tinker took the opposite view, insisting that Zimmerman was actually unlucky in his finest season. “Why, do you know, that fellow loses more hits through hard luck catches than I make,” Tinker said. “He has the strongest pair of hands and arms that I have ever seen on a human being.”

Zimmerman became the toast of Chicago. The year 1912 was the pinnacle of magician Harry “The Great” Houdini’s popularity, and the city’s sportswriters took to calling their third baseman “The Great Zim.” Never one for modesty, Zimmerman started referring to himself in the third person under his new nickname. Chicago loved him for that, too.

Soon Zimmerman pulled a disappearing act of his own.

He enjoyed another fine offensive season in 1913, batting .313 and driving in 95 runs, but his swelled head led to confrontations with management and acrimonious contract negotiations became an annual event. More than once Zimmerman “retired” from the game, only to un-retire once spring training rolled around. What money he did receive, he spent quickly—and often unwisely. “Zim never knew how much money he had because he made the team’s secretary his banker and ‘touched’ the secretary for five and ten-spots until his salary was gone, then economized until the roll was replenished,” wrote one observer, who noted Zimmerman’s fetish for lavish neckties.

The indiscriminate spending might have been amusing had it not come at the expense of his new family. In 1912 Henry married the 17-year-old Helene Chasar, who one year later gave birth to a daughter, Margaret. The marriage soon deteriorated, however, and in January 1915 Chasar sued Zimmerman for alimony. “Although the wife alleges Zimmerman is paid $7,200 a year by the Chicago Club for his services,” one Chicago newspaper reported, “she alleges he has not sent any money to support her in some time, excepting a five-dollar gold piece which was sent her as a Christmas present for their daughter.” The couple divorced in March 1916.

Before long the discord began to take its toll, and his performance on the field started falling short of expectations. In 1915 he suffered through his worst season, batting just .265 with a paltry .379 slugging percentage. For the first time, but not the last, pernicious rumors of Zimmerman’s dishonesty began to surface. That year The Sporting News described him as “one of the most interesting problems of baseball,” a player whose “energy [is] being misdirected and talents largely wasted.” Zimmerman developed a reputation throughout the league as a “bad actor,” prone to sudden, inexplicable mood swings that dictated the amount of effort he put forth on any given day. The Cubs finally tired of him and dealt him to the New York Giants for Larry Doyle in August 1916. At the time of the trade, Zimmerman was under a ten-day suspension for “laying down on the job.” Most managers wanted nothing to do with the erratic Zimmerman, but manager John McGraw prided himself on his ability to rehabilitate players deemed hopeless by other baseball men.

Cellar-dwellars in 1915, the Giants were slumping toward another losing season in 1916 until the Zimmerman trade, when they suddenly caught fire and reeled off a record 26 consecutive victories. Between Chicago and New York, Zimmerman collected a league-leading 83 RBIs, but his reputation preceded his accomplishments in the eyes of many observers. “Zimmerman might have been the greatest player, but he wasn’t,” dryly noted F. C. Lane of Baseball Magazine. “Zimmerman has not, of late years, played his best game. Any time he wishes to exert himself he has the natural ability, but his temperament has been a big handicap.”

In 1917 Zimmerman responded to his critics with his best hitting performance in four years. His .297 batting average was his best mark since 1913 and his 102 RBIs paced the circuit by a comfortable margin, helping the retooled Giants run away with the pennant. Zimmerman’s improved performance also had Lane singing a different tune: “We know nothing of Zimmerman’s qualifications for alderman or a seat on the school committee, but he certainly can play third base.” His triumphant season concluded in the worst manner imaginable, however, when he batted just .120 and committed three errors in the Giants’ loss to the Chicago White Sox in the 1917 World’s Series.

It was Zimmerman’s role in a botched rundown in the sixth and final game that forever sealed his fate as the goat of that Series. With the game scoreless in the top of the fourth inning, Heinie made a bad throw on an Eddie Collins grounder, allowing Collins to advance to second. Dave Robertson then dropped Joe Jackson‘s fly ball, putting runners at second and third with no outs. At that point Happy Felsch grounded back to the pitcher, Rube Benton, who threw to Zimmerman at third, catching Collins in a rundown. Zimmerman threw the ball to catcher Bill Rariden, but when Rariden tossed the ball back to Zimmerman, the clever Collins slipped past the catcher and sprinted for home. Both Benton and Giants first baseman Walter Holke neglected to back up the play, leaving home plate unattended. With a foot pursuit his only option, the lumbering Zimmerman tried unsuccessfully to chase down the speedy Collins, who slid across home plate with what proved to be the Series-winning run.

The play was not Zimmerman’s fault, but that didn’t matter—the press mercilessly ridiculed him. The New York Times called the play “Zimmerman’s deathless outburst of stupidity.” “The great crowd shook with laughter and filled the air with cries of derision at one of the stupidest plays that has ever been seen in a world’s series,” reported the Times. “Zim thought it was a track meet instead of a ball game and wanted to match his lumber wagon gait against the fleetest player in the game.” Heinie emphatically defended his actions, and Collins himself exonerated the rival third baseman of all blame, but to no avail. More than a half-century later, newspaper reports of Zimmerman’s death carried this headline: “Giants’ Heinie Zimmerman Dies; Committed 1917 Series ‘Boner.’”

Unfairly branded as a buffoon in the papers, Zimmerman emerged from his final World’s Series bitter and disillusioned. In 1918 he suffered through one of his poorest seasons, his batting average falling to .272 and his RBIs plummeting to 56. Lane noted a change in the former star. “He seemed to suffer from the all-round slough of discouragement which engulfed the Giants’ hopes,” remarked Baseball Magazine‘s star reporter after the season. Partly because of Zimmerman, the Giants failed to duplicate their 1917 success, and as the season progressed Zimmerman’s effort started to flag. In July McGraw bawled him out in public and then benched him for failing to run out a pop fly.

For years Zimmerman’s inconsistency had fueled suspicion among some members of the press that he was a dishonest player, but prior to 1919 the accusations never rose above the level of vague insinuation. Words like “erratic,” “episodic,” and “problematic” left unspoken the fear shared by many that Zimmerman might have been selling ballgames. The events of 1919, however, removed all doubt. Before the season the Giants acquired the most notorious game-thrower of them all, Hal Chase, from the Cincinnati Reds. McGraw believed that he could reform the corrupt Chase, but instead of turning over a new leaf, Prince Hal repaid McGraw’s kindness by shifting his game-fixing operations to a new city, recruiting Zimmerman as his new sidekick.

For the second consecutive year Zimmerman performed below expectations, but this time the root cause may have been something other than frustration or distraction. As the Giants limped through another disappointing campaign, Zimmerman and Chase became inseparable friends, often hanging out with gamblers in bars and restaurants. In such an environment, what happened next was probably inevitable. On September 11, Zimmerman approached pitcher Fred Toney after the first inning of a game in Chicago and informed him that “it would be worth his while” not to bear down on the Cubs. One inning later, Toney asked to be removed from the game, but Zimmerman didn’t stop there. That same evening, Chase and Cubs infielder Buck Herzog informed Benton that he could “make some easy money” by letting Chicago win. When Benton beat the Cubs anyway the following afternoon, Zimmerman approached him in the hotel lobby after the game and said, “You poor fish, don’t you know there was $400 waiting for you to lose that game today?”

There was more. A few days later in St. Louis, Chase and Zimmerman offered outfielder Benny Kauff $125 per game to help them throw games. By that time, word of the pair’s activities had reached McGraw, who promptly suspended Zimmerman from the team. (Chase remained with the team for two more weeks.) At the time, McGraw’s public explanation for Zimmerman’s suspension was that he had broken curfew, but shortly thereafter McGraw and Giants owner Charles Stoneham got Zimmerman to confess to his real offenses. It was the end of his major league career.

In an earlier era Zimmerman might have been able to continue in the profession with some other club, but any such hope was forever lost with the public revelation of the Black Sox scandal. In September 1920, a grand jury was convened to investigate gambling in baseball, and it was at those hearings that Zimmerman’s misdeeds were brought to light. McGraw and Toney both testified to Zimmerman’s actions at the end of the 1919 season. In an affidavit, Zimmerman admitted to offering bribes to Toney, Benton, and Kauff, but insisted he did so only at the request of an unnamed Chicago gambler. “He made me no personal offer, but asked me to deliver this message to these three men,” Zimmerman claimed. “Although I was not to benefit by it, I went to Kauff, Toney and Benton and delivered the message.” He insisted that he had played to win the suspect games.

No one believed Zimmerman, but what he had confessed to was damning enough. Though never officially banned, he became persona non grata throughout Organized Baseball. Once, when Zimmerman tried to play a semipro game at a park in Harrison, New Jersey, owned by someone who was connected with Organized Baseball, he was asked to leave the grounds before the game even started. “This was a fine deal,” Zimmerman glumly told reporters.

In the absence of any other livelihood, Zimmerman remarried and went back to working as a plumber in the Bronx, though before long he supplemented that work through less reputable sources of income. In 1929-30 Zimmerman operated a speakeasy with the famous racketeer Dutch Schultz, becoming closely connected with New York’s most ruthless mobster. In 1928 Zimmerman’s brother-in-law, a top Schultz lieutenant, was fatally shot outside a West 54th Street nightclub. In 1935 Zimmerman was named as an unindicted co-conspirator in the government’s tax evasion and conspiracy case against Schultz. The government lost the case, but a few months later Schultz was gunned down in a Newark restaurant.

Ignored and forgotten, Zimmerman reassumed the blue-collar lifestyle that was the inheritance of his childhood. In his last job he worked as a steamfitter for a construction company. Heinie Zimmerman died in New York City on March 14, 1969, after a brief battle with cancer. He is buried in Woodlawn Cemetery, a short drive south from his boyhood home.

Note: A slightly different version of this biography appeared in Tom Simon, ed., Deadball Stars of the National League (Washington, D.C.: Brassey’s, Inc., 2004).

Sources

For this biography, the author used a number of contemporary sources, especially those found in the subject’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Full Name

Henry Zimmerman

Born

February 9, 1887 at New York, NY (USA)

Died

March 14, 1969 at New York, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.