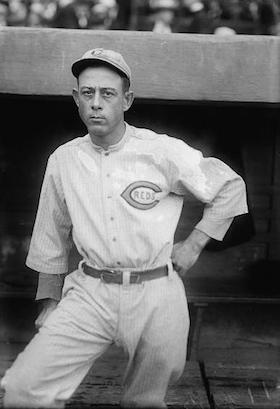

Bill Rariden

A traveler traversing U.S. 50 across Southern Indiana might not notice anything special about the town of Bedford. But to one of its native sons, the town must have been very special indeed. His affinity for his home town earned Bill Rariden the nickname “Bedford Bill.” In his 12 years in the major leagues, Rariden participated in one of the most exciting plays in World Series history and in the Series that might have destroyed the game, but for the actions of Kenesaw Mountain Landis and the heroics of Babe Ruth. But his heart was never far from Bedford.

A traveler traversing U.S. 50 across Southern Indiana might not notice anything special about the town of Bedford. But to one of its native sons, the town must have been very special indeed. His affinity for his home town earned Bill Rariden the nickname “Bedford Bill.” In his 12 years in the major leagues, Rariden participated in one of the most exciting plays in World Series history and in the Series that might have destroyed the game, but for the actions of Kenesaw Mountain Landis and the heroics of Babe Ruth. But his heart was never far from Bedford.

William Angle Rariden was born on February 5, 1888, in south-central Indiana in the small Lawrence County community of Bedford, a rural area surrounded by beautiful wooded hills and valleys. Rariden was born and raised, lived and died, and was buried in Bedford. Even when he was playing baseball in far-away places he maintained a home in Bedford. It is easy to see why he was called Bedford Bill.

Bill Rariden was a Hoosier to his very core. His parents, Sarah Elizabeth Ferguson and Dr. Charles E. Rariden were both born in Indiana, as were Bill’s three siblings, his wife Ruby Jean Sellers, and their two daughters Elizabeth Jeanette and Wilma. Charles Rariden was a physician. Although country doctors in rural Indiana in the late nineteenth century seldom became wealthy, most were able to provide for their families, and young Bill did not face the hardscrabble childhood that many contemporary baseball players endured.

The youngster learned the game of baseball on the playgrounds of his home town. Not long after graduating from Bedford High School, he started his professional career with the Canton (Ohio) Chinamen in the Class B Central League in 1907. One of his Canton teammates, Rube Marquard, was the best pitcher in the league and made it to the majors the very next year. It took Rariden a little longer to reach The Show. In 1908 the Canton club now called the Watchmakers migrated to the Class C Ohio-Pennsylvania League, and Rariden played for them for most of the next two seasons. On August 8, 1909, he was purchased by the Boston Doves of the National League. Four days later, he made his major-league debut.

The right-handed catcher was 21 years old, stood 5-foot-10, and weighed 168 pounds. He played for the Doves (or the Braves as they were later called) for almost five years, the longest stretch he ever played for one club in professional baseball. Rariden had difficulty hitting major-league pitching, but he was an excellent defensive catcher and had a knack for handling pitchers. These skills were sufficient to keep him in the majors, even though he never hit more than .236 in Boston.

In 1914 the new Federal League challenged the National and American circuits for major-league status, raiding the two established circuits. Bill Rariden was among the players who defied the reserve clause in their contracts and jumped to the new loop on February 3, 1914. Back home in Indiana with the Indianapolis Hoosiers, he immediately became one of the best catchers among the Feds. In his two seasons in the league, he led the loop in both putouts and assists each year. In 1915 he also led in errors by a catcher. The word must have gotten around that Rariden was easy to run on. In both of his Federal League seasons, he led the loop in stolen bases allowed and in baserunners thrown out. In 1915 he cut down 138 would-be base stealers, while allowing 136 successful attempts. Throwing out more than half of attempted steals is a notable accomplishment for any catcher.

Despite winning the pennant in 1914, the Hoosiers were unable to make it financially in Indianapolis, and the club was transferred to Newark in 1915. So during his entire professional career Rariden got to play in his beloved home state only one season. For several reasons (mostly economic) the Federal League was unable to survive. The league closed shop after the 1915 season, and players were dispersed to the two established leagues. On December 23, 1915, the New York Giants purchased Rariden.

Rariden had two good years in New York, playing in more than 100 games in both 1916 and 1917. He led the National League in putouts by a catcher in 1916. In 1917 he hit .271, his highest major-league average.

The Giants won the National League pennant in 1917 and faced the Chicago White Sox in the World Series. Rariden started the Series on the bench, as manager John McGraw elected to start Lew McCarty in the catcher’s position. However, McCarty was injured in Game Two, when Nemo Leibold crashed into him in a play at the plate. Rariden replaced McCarty

and appeared in five of the six games, hitting a robust .385, more than 100 points higher than he had ever hit in a regular season. He is mainly remembered, though, for his minor role in one of the most memorable plays in World Series history. It was in Game Six, with the White Sox leading, three games to two. Pitchers Red Faber of the Sox and Rube Benton of the Giants both pitched shutout ball for the first three innings. In the fourth frame Eddie Collins hit a grounder to third. Heinie Zimmerman fielded the ball, but threw it past first baseman Walter Holke for a two-base error. Shoeless Joe Jackson then hit a fly ball to right field, which was dropped by Dave Robertson. Jackson was safe at first while Collins advanced to third. Happy Felsch hit one back to the box, and Collins strayed off third. Benton threw to Zimmerman, and Collins was trapped between third and home. He danced back and forth, trying to keep the rundown alive, so Jackson and Felsch could advance as far as possible before he was tagged out. Zimmerman threw the ball to Rariden, but when the catcher tossed the ball back to third base, Collins slipped past Rariden and sprinted for home. Both Benton and Holke had neglected to back up home plate, so the dish was uncovered. Zimmerman had no one to throw to. His only choice was to try to catch the speedy Collins, so he chased him home. Big, lumbering Zim had no chance of catching the much faster Collins, who slid across home plate for the first run in what turned out to be the deciding game of the Series, as Faber protected the lead.

The play was not Zimmerman’s fault, but that didn’t matter to the press and the fans who mercilessly ridiculed him. As The Sporting News put it, “The Great Zim became the Great Goat.”1Zimmerman’s goat horns followed him to the grave. When he died more than a half-century later, newspaper headlines read “GIANTS’ HEINIE ZIMMERMAN DIES; COMMITTED 1917 SERIES BONER.”2 Zimmerman quite naturally was furious at the unfair opprobrium heaped upon him. Home plate was unprotected. “Who the hell was I going to throw the ball to? Klem?”3 (Bill Klem was the home plate umpire.) Either Benton or Holke would have been a more suitable object of scorn than the hapless Zim.

Years later one article in The Sporting News said Rariden was the actual goat,4 but that definitely was a minority opinion. Rariden’s role in the famous play was seldom discussed. The quick, clever, agile Collins simply outmaneuvered him. He didn’t recover in time to join Zimmerman in the fruitless dash down the third base path.

Collins himself exonerated both Rariden and Zimmerman, attributing the play to his own talent. “It worked out exactly as I had planned,” he said. “Benton saw me off third and presumably breaking for home. He threw to the Giants’ catcher, Bill Rariden. I started back to third, with Zimmerman behind me and Rariden coming up the line. Rariden had held the ball as I danced along the baseline. When he tossed to Zimmerman behind me he had stepped a foot or so out of the baseline. I, fortunately, whirled around fast, saw he was practically beside me and home plate was uncovered. No one had backed up Rariden on the play. I breezed by Rariden and set sail for the plate. There was no one to hinder me, and Zimmerman had only one recourse. He had no one to throw the ball to, since Rariden was then out of the play. He had to chase me.” (Collins’s memory was not perfect. Benton threw to Zimmerman, not Rariden.)

Rariden’s playing time was diminished in 1918, as he split backstop duties with McCarty. On February 19, 1919, Rariden was traded along with first baseman Walter Holke to the Cincinnati Reds for the infamous Hal Chase, who was soon to be blacklisted by Organized Baseball for fixing games. Holke was traded almost immediately to the Boston Braves for a backup third baseman named Jimmy Smith and cash.

In 1919 Rariden split catching duties with the veteran Ivey Wingo, appearing in 74 games compared to 76 for Wingo. Neither was much of a hitter, but both were excellent defensive catchers and adept at handling pitchers. The Reds won the National League pennant in 1919, so for the second time in three years Rariden was in the World Series, and for the second time in three years he was facing the Chicago White Sox. This was the most controversial World Series ever played. Although the Reds won their first-ever National League pennant and their first-ever World Series title, the championship crown was tarnished by evidence that some members of the Chicago White Sox had conspired with gamblers to throw the Series. But as far as the Reds were concerned, they won the title, fair and square. To a man, they believed they would have won, fix or no fix.5

A great deal has been written about the 1919 World Series, much of it inaccurate. Some have said Chicago had been a heavy favorite.6 Some have called the Reds win an “upset.”7 Others have recognized the reality that the White Sox were not favored, but assert they should have been. Sportswriter Lee Allen wrote, “By any logical analysis the White Sox should have been the favorites.”8 Tom Meany agreed, “The odds favored the Reds when they should have favored Chicago.”9 These assertions were based on American League clubs having won the World Series four times in a row, including the 1917 triumph of the Chicago White Sox over the New York Giants.

Overlooked in this analysis were two important facts: the 1919 Reds, with a .686 winning percentage in the regular season, were a much stronger team than the Giants, whose winning percentage in 1917 was .636; and the 1919 White Sox were not at full strength. Red Faber, who had won three games for the Sox in the 1917 Fall Classic was ill and unavailable for the 1919 Series. Hall of Fame catcher Ray Schalk said that if Faber had been able to pitch there would have been no Black Sox scandal.10 Author James Farrell wrote that it has often been said that if Faber had been in good health he might have won the Series for the Sox.11

A year later eight members of the White Sox were banned from baseball for life by Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis for allegedly throwing the Series. Landis’s actions restored confidence in the integrity of the game. Babe Ruth’s prodigious home run clouting drew fans to the ballparks in record numbers. Baseball survived.

Rariden appeared in five of the eight games of the 1919 World Series, hitting an unimpressive .211 and making no headlines.

In 1920 Rariden’s playing time was reduced to 39 games. He played his final major-league game at Forbes Field on October 2, 1920, as the Reds lost the third game of Major League Baseball’s last tripleheader to the Pittsburgh Pirates, 6-0. Not surprisingly, Rariden was hitless in his final big-league game.

Out of the majors at the age of 32, Rariden was not yet ready to hang up his cleats. In 1921 and 1922 he played for the Atlanta Crackers in the Class A Southern Association. In 1922 he tried his hand at being a player-manager and came up short. His Crackers went 55-97, finishing in last place. At 34 Rariden was finished with professional baseball.

For a time in the 1920s Rariden lived on a farm in Shawswick Township, just outside the Bedford city limits. He soon returned to his home town and bought and operated a filling station there for many years.

William Angle Rariden died of a heart attack at the age of 54 in Bedford, Indiana, on August 28, 1942. He was buried in the Green Hill Cemetery in Bedford, near the grave of his father and several other relatives. Bedford Bill was home to rest.

Sources

The principal sources not referenced in the Notes are ancestry.com. and sabr.org.

Notes

1 The Sporting News, November 2, 1944.

2 Tom Simon, ed. Deadball Stars of the National League. Washington: Brassey’s, 2004, 127.

3 Tom Meany, Baseball’s Greatest Teams, New York: A. S. Barnes, 1949, 88.

4 The Sporting News, August 16, 1950.

5 Meany, op. cit., 162

6 John Thorn, et. al., eds. Total Baseball, 8th ed, Wilmington, DE: Sport Media, 2004, 96.

7 Mike Shatzkin, ed., The Ballplayers, New York: Arbor House, 1990, 186.

8 Lee Allen, The Cincinnati Reds, New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1948, 141.

9 Meany, op. cit., 158.

10 Washington Post, February 5, 1964.

11 James T. Farrell, My Baseball Diary: A Famed American Author Recalls the Wonderful World of Baseball, Yesterday and Today. New York; Barnes, 1957, 201.

Full Name

William Angle Rariden

Born

February 5, 1888 at Bedford, IN (USA)

Died

August 28, 1942 at Bedford, IN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.