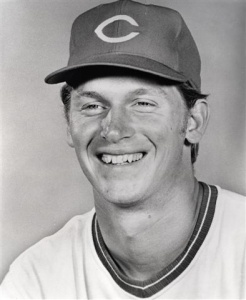

Tom Carroll

Recalled from the minor leagues near midseason by the Cincinnati Reds in both 1974 and 1975, Tom Carroll was a hard-throwing right-handed pitcher who began his career by winning his first four decisions as a starter in 1974. With the Big Red Machine cruising in 1975, Carroll’s four wins helped stabilize the staff when their ace Don Gullett was injured in mid-June. Once hailed as the Reds’ top minor-league pitching prospect, Carroll was beset by arm miseries that prematurely ended his major-league career after those two seasons.

Recalled from the minor leagues near midseason by the Cincinnati Reds in both 1974 and 1975, Tom Carroll was a hard-throwing right-handed pitcher who began his career by winning his first four decisions as a starter in 1974. With the Big Red Machine cruising in 1975, Carroll’s four wins helped stabilize the staff when their ace Don Gullett was injured in mid-June. Once hailed as the Reds’ top minor-league pitching prospect, Carroll was beset by arm miseries that prematurely ended his major-league career after those two seasons.

A native of Oriskany, New York, Thomas Michael Carroll was born on November 5, 1952, the first of seven children (four boys and three girls) born to Daniel and Jeanette Carroll. In the town of 1,200 residents in central New York, Tom grew up in a house with an old, fenced-in tennis court. “I recall my father taking me [on the tennis court] one day,” he said about one of his first memories about baseball, “and tossing me a red rubber ball and how I liked to hit.”1 With his brothers, Tom modified the court, removed the net, and created a miniature baseball diamond with their own set of rules. “We used the tennis court to great advantage,” he recalled. “Hitting the ball over the fence meant a lot of running, so we made a rule that if you hit the fence with a line drive it was a home run and if you hit it over the fence it was an out. We learned early on to hit line drives.”2 Learning to hit, field, and throw on the court, Tom and his brothers were well prepared when they began playing Little League baseball. When his father accepted a job as a personnel executive at Allegheny Ludlum, that necessitated a move to Pittsburgh in 1965, Tom remained with his grandmother in Oriskany so he could finish the season as a pitcher and shortstop on Oriskany’s highly competitive Pony League team, which played in a statewide tournament.

Starring as a pitcher and fielder from 1968 to 1970 on the baseball team at North Allegheny High School in Pittsburgh (where he also played junior-varsity basketball), Carroll had a unique opportunity playing baseball in the summer. “The Little Pirates, a team sponsored by the Pittsburgh Pirates, recruited in the metropolitan area, is where I really got my basic training as a pitcher,” Carroll said. His team was managed by a former minor-league player, George Schmidt. “I actually made the team as an outfielder. I was playing left field one day and someone hit a ball [to me] with a runner on third base. I was able to get a good jump on the ball and threw him out. From that point on I was told that I’d be a pitcher.”3 Playing about 60 games per summer and instructed by Pirates scouts, Carroll attracted attention as a tall, hard-throwing pitcher.

After graduating from high school at the age of 17, Carroll was drafted by the Reds in the sixth round of the 1970 amateur draft. “There was some question about whether I would sign or go to college,” he recalled. “I had a scholarship offer from the University of Iowa and I had signed a letter of intent.” Even after Elmer Gray, the Reds’ scout for the area, visited him at home, Carroll was unsure what to do. “I didn’t make the choice right away. The Reds flew me and my father to Cincinnati and put us up in a hotel. They invited us to Riverfront, which was under construction. Russ Nixon, who’d be my coach the next two years, gave us a tour.” Impressed and excited by the immediacy of major-league baseball, Carroll signed for “few-thousand-dollar bonus” and an allowance for eight semesters of college.4

Carroll reported to Bradenton, Florida, in June 1970 with other Reds draftees and young players to attend a two-week training camp, after which the Reds assigned players to either the GCL Reds in the Rookie Gulf Coast League or the more competitive Class A Sioux Falls (South Dakota) Packers in the short-season Northern League. “It was clear that Sioux Falls was the team players competed for,” Carroll said. The instructional camp introduced the players to the Reds’ core philosophy of mental awareness and fundamentally sound baseball. “Each morning, [minor league instructor] Ron Plaza would walk into the players’ area and start a whiteboard talk with ‘Gentlemen, today we’re going to go over the …’ ” Carroll recalled. “Ron’s depth of knowledge on fundamentals was great and the Reds were noted for having players that were a cut above in that regard and it all came back to those whiteboard sessions and related demonstrations on the field.”5

Along with future Reds Ken Griffey, Will McEnaney, Joel Youngblood, and Pat Zachry, the 17-year-old Carroll was assigned to Sioux Falls. Carroll found himself away from home for the first time, “I had a great roommate, Jim Mavroleon,” he said. “He looked out for me and it made the transition easier.”6 (Mavroleon left Organized Baseball after two seasons in the Reds’ farm system.) Carroll tied for the lead on the short-season team with four wins in nine decisions and had an impressive 2.83 earned-run average in 86 innings.

Owner of a fastball and curveball, Carroll began to experiment with a changeup at Sioux Falls under manager Russ Nixon. Assigned to the Florida Instructional League after the season, Carroll honed the pitch. “Scott Breeden, who was our minor-league pitching instructor, taught me how to throw (the) changeup. I refined it that season in winter-league ball and used it to some effect in Tampa. It became a great pitch for me. I could put it where I wanted, it sank, and [I had my motion] down.”7

With great confidence, Carroll began the 1971 season with the Tampa Tarpons in the Class A Florida State League and achieved immediate success which he credited to his close work with Nixon, who had been moved to Tampa as manager. “Russ had been around … and had caught a lot of pitchers. In my career, the catchers were most influential.”8 While tying for the league lead with 18 victories (and only 5 losses) and a sparkling 2.39 ERA in 192 innings, Carroll was tabbed by Reds’ general manager Bob Howsam as the team’s top young pitching prospect.9

After studying at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh in the offseason, Carroll moved to Florida, where he found a job to support himself. “I worked for a company and we moved wire bales. It probably was not the wisest thing to do in the offseason. And it affected me.”10 Assigned to the talented Trois-Rivieres (Quebec) Aigles in the Double-A Eastern League in 1972, Carroll complained of tight muscles all season and was limited to 18 starts and only one complete game in 104 innings pitched. Struggling with velocity and control, he limped to a 6-10 record and saw his ERA jump almost a full run per game, to 3.38.

Determined not to repeat his year with Trois-Rivieres, Carroll pitched in the Florida Instructional League after the season and was committed to improving his physical fitness and endurance, but he stayed away from any heavy lifting. “I really worked hard in the offseason to get my legs in the best shape they had ever been in. And then over the years I found that it really helped.”11 The Reds were impressed with Carroll’s progress despite his 1972 record and promoted him to Triple-A, the Indianapolis Indians, for the 1973 season.

Beginning his fourth year of minor-league ball, Carroll played for Vern Rapp, a longtime former minor-league catcher who had developed a reputation for producing major-league players since taking the reins of the Reds’ top farm team in 1969. “Vern took a genuine personal interest in the players … developing not only a player, but also a person,” Carroll said. “You sensed that as a young person. That made instruction in pitching more digestible. And he had a catcher’s knowledge of pitching.”12

Described by The Sporting News as “lean,” the 6-foot-3, 190-pound Carroll was in the best shape of his life and his pitching responded.13 “After spring-training workouts,” he said, “I’d play handball to keep my legs in shape and my agility, but also to stretch my arm out.”14 While completing four games in a six-game stretch of starts in late May and June, Carroll tossed a two-hit shutout against the division-leading Iowa Oaks on June 6 and then a one-hit gem over the Wichita Aeros on July 23, prompting manager Rapp to boast, “Early in the year, Tom was a seven-strikeout, seven-walk pitcher. But he has really come around well. I think the teams he’s faced will argue that he’s not just a thrower anymore. I guess hard work, desire, and determination are the reasons why he’s improved.”15 Deflecting attention, Carroll maintained that his success was due to Rapp’s help with his mechanics and delivery. “He worked with me on my motion and it paid off,” Carroll said of his improved control. “I learned a lot from him. His instruction was instrumental in me becoming a major leaguer.”16

Though still inconsistent (a ten-walk outing against the Evansville Triplets on August 18 was followed by a masterful complete-game victory with 13 strikeouts over Iowa on August 24), Carroll was considered the top pitcher in the American Association with Omaha’s Mark Littell, a Kansas City Royals farmhand.17 With 15 wins and a 3.88 ERA in 174 innings pitched, Carroll was added to the Reds’ 40-man roster after the season.18

The 21-year-old Carroll went to his first spring training with the Reds in 1974, and was among the last players cut. He moved to the minor-league camp, and was assigned to Indianapolis, which was stacked with pitching prospects and veterans. Thirteen of the 16 pitchers on the Indians’ roster that season had or would have major-league experience. Carroll was unable to establish the kind of dominance he had the season before, and his ERA hovered around 5.00 in mid-May. “In 1974 I was in a rhythm where I’d have three good starts, a so-so one, and then a bad one,” said Carroll. “I thought that was pretty good for a young guy in Triple-A. Vern said, ‘No, no, if you want to get to the major leagues, you need to string together seven or eight good starts. And on the days when you don’t have your great stuff, you still gotta have a good start.’ That was sobering, but it gave me a target.”19

On May 24 Carroll pitched the best game of his life, a no-hitter over the Omaha Royals. “I remember how easy it was. I didn’t have the smoothest motion or the best control [in my career],” Carroll said with a chuckle about his 104-pitch masterpiece. “It was just one of those days when things just happen naturally.”20 He got stronger as the game progressed and said that he drove toward the plate more forcefully with his left arm in order to keep his fastball down.21

Sporting an 8-4 record in 16 starts, but also with a 4.92 ERA in 97 innings, Carroll was called up by the Reds in July to replace Roger Nelson as the fifth starter on a strong staff that included Don Gullett, Clay Kirby, Jack Billingham, and Fred Norman. “Vern Rapp said he wanted to see me,” Carroll said of his recall. “We were in the Hotel Fort Des Moines in Des Moines Iowa. I really wasn’t thinking I’d be going to the big leagues. Rapp said ‘Son, you’re going to the big leagues.’ That had to be one of the greatest days of my life.”22

With temperatures approaching 100 degrees on the Astroturf at Riverfront Stadium, Carroll made his major-league debut on July 7, 1974, in Cincinnati and earned the victory by pitching two-hit, one-run ball for seven innings against the NL East-leading St. Louis Cardinals. After setting down the side in the first inning, Carroll gave up a home run to Ted Simmons in the second. Striking out six and walking six, Carroll threw 101 pitches and was relieved by former Indianapolis teammate and his Reds roommate, Will McEnaney who had been called up with him.

In his next start, on July 12, Carroll pitched in front of friends and family in Pittsburgh and led the streaking Reds to their eighth win in nine games as he won game two of a doubleheader, 4-3. Pitching into the ninth inning, Carroll was in command the entire game except for the third inning, when the Pirates scored three unearned runs after two were out. “This kid is just like Don Gullett. He’s quiet, never complains, but he’s got [courage],” said Reds manager Sparky Anderson.23 After a no-decision against St. Louis where he singled off his boyhood idol Bob Gibson, Carroll won again by pitching eight innings of four-hit ball against the San Diego Padres, surrendering their only run on an RBI-double to Cito Gaston in the fourth inning. “Carroll has a mind like a sponge,” said Reds pitching coach Larry Shepard, who was impressed with his ability to throw strikes. “He soaks everything up you tell him.”24

The Reds’ bats had been abnormally quiet in the first quarter of the season, causing the reigning pennant winners to fall ten games out of first place by the time Carroll was called up. With the offense of the Big Red Machine hitting full stride in July and August, Carroll pitched six innings on August 11 against the Mets in New York to win his fourth consecutive decision, leaving the Reds 5½ games behind the division-leading Dodgers. “We’re making a man out of Tom in a hurry, throwing him right into the middle of this pennant race,” said Sparky.25 With a fastball made more effective with his changeup, Carroll’s success made for good copy. “Back in Indianapolis, I just reared back and tried to strike out the hitters. Up here, I try to keep the ball down low,” Carroll said.26

But after Carroll made a few ineffective starts and the pennant race tightened, Anderson juggled his rotation during the last month of the season, preferring to pitch his four established starters. After his 4-0 start, Carroll lost three decisions, started just three games and relieved in three in September and early October. “I got off to a nice start,” he said. “My view was that as long I was in the rotation, I’d find my way. Unfortunately, after a bad game or two, I’d be pulled. For someone who pitched every fourth or fifth day for years, it was harder to get into a rhythm when you had lapses between starts.”27 While the Reds finished in second place behind the Dodgers (in the NL West), Carroll finished 4-3 with a 3.68 ERA in 78⅓ innings pitched.

Though the short-hair and no-facial-hair policy of the Reds during those years may be well known, other matters of attention to detail may not be. “The Reds were strict,” Carroll recalled. “Once we were in uniform, we had multiple sets. The general manager [Bob Howsam] noticed that my colors were slightly off – that my pants and shirts were not matching – and he called down and I had to change.” The Reds players got along well with one another and a genuine sense of camaraderie ruled. Carroll said that rookies were treated well. “Pete Rose was especially good to the young players, inviting them to his house, taking them out for dinner on the road,” he said. “Pete doesn’t get a lot of good press. Morgan and Bench also looked out for the younger players. Terry Crowley, Clay Carroll, Merv Rettenmund, Jack Billingham, Fred Norman also come to mind in that way.”28

With Gary Nolan returning to Cincinnati in 1975 after missing almost two years with shoulder problems, the Reds’ staff reckoned to be one of the deepest in the major leagues in 1975. Despite his success the previous season, Carroll found himself the sixth starter in a five-man rotation and was assigned to Indianapolis so that he could pitch every day. Initially refusing to report to the Indians and drawing a short suspension, Carroll returned to Vern Rapp’s team. With a record of six wins and six losses in 16 starts, Carroll earned another call-up to the Reds in mid-June when staff ace Don Gullett fractured his thumb on a line drive by the Braves’ Larvell Blanks. Though his ERA was significantly lower than in 1974 (3.09 from 4.92), so too was his strikeout ratio, causing Carroll deep concern. “In 1974 I’d been pitching better in Indianapolis than in 1975,” he said. “I could feel, despite the fact that I was called up, that my arm was not the same. I was struggling more with velocity.”29

With the Reds in first place, Carroll reeled off 7-3 and 2-0 victories over the Astros and Braves after his promotion. He lasted just 1⅔ innings during his third start in Cincinnati versus Houston on June 30, but started again two days later and, after surviving a very shaky first inning, pitched more effectively, but not enough to keep his spot in the rotation. Through mid-July, he saw intermittent duty as a long reliever and spot starter, but lacked consistency. On August 2 he pitched shutout ball for 6⅓ innings against the Dodgers for his fourth and what proved to be his last major-league win. “I was concerned because my arm was not the same. … I was living on my wits in 1975. I could feel my arm going. It wasn’t so easy to throw hard anymore.”30 When Gullett returned in August, Carroll was sent back to Indianapolis.

Reflective and articulate, Carroll told the author, “I had a realistic assessment why [I was sent down]. I can’t be angry. I can be frustrated, but not angry with the decision. The nice thing about pitching is your performance is captioned clearly.” He was called up again in September, too late to be added to the postseason roster, relieved twice, giving him 12 appearances for the season (seven starts), and finished with four wins in 47 innings and a 4.98 ERA. Though he couldn’t play, he remained in uniform either in the dugout or the bullpen for the NLCS against Pittsburgh and the Reds’ dramatic World Series victory over the Boston Red Sox. For a 22-year-old whose passion was baseball, it was frustrating to watch but not participate, especially having contributed during the regular season. The team voted him a three-quarters World Series share even though he was on the roster for just half a season. One of his few sources of disappointment: “I didn’t hear anything about a World Series ring over the winter. The rings were passed out during spring training. I guess somewhere along the line it was determined I didn’t deserve a ring.”31

Spring training in 1976 was cut to three weeks after the owners locked out the players in 1976. With the trade of Clay Kirby and Clay Carroll in the offseason, and lingering concern over Gullett’s injury the season before, Carroll was considered one of the front-runners for a spot in the rotation. Facing stiff competition from Pat Darcy, a surprise 11-game winner in 1975, and top prospects Santo Alcala and Pat Zachry, the 23-year-old Carroll still suffered from a lack of velocity and was again among the last pitchers cut and assigned once again to Indianapolis.

Playing for manager Jim Snyder, Carroll occasionally displayed his once-promising potential – throwing a one-hit shutout over the Tulsa Oilers on June 26 – but struggled with the Indians, going 9-12 with a bloated 5.38 ERA. With their deep farm system and young starters, the Reds found Carroll expendable and traded him in the offseason to the Pittsburgh Pirates for pitcher Jim Sadowski (who never appeared in a game for the Reds), thus initiating Carroll’s strangest season in baseball.

Carroll remained a Pirate for only a month before he was chosen by the Montreal Expos in the annual Rule 5 draft after the Pirates’ did not add him to their 40-man roster. Expos general manager Charlie Fox was excited about offering Carroll a change of scenery, saying, “We honestly believe he’s a young man with big-league potential.”32 Working with Expos pitching coach Jim Brewer and roving instructor Eddie Lopat in spring training, Carroll had a good shot to make the team, which had lost 107 games in 1976.33 “I had the best spring training I ever had statistics-wise,” he said, “but I wasn’t throwing hard and I think it was pretty obvious. For someone who had been primarily a fastball pitcher, it was not good. I was cut on the last day.”34

Assigned to the Denver Bears in the American Association to start the 1977 season, Carroll struggled to throw his fastball and surrendered 19 earned runs in 9 innings. “My arm was getting so bad that I asked if I could go to West Palm Beach,” he said. “I had had a good year in the hot weather in Florida [in 1971] and I thought I could loosen things up.”35 Playing for first-year manager Felipe Alou in the Class A Florida State League, Carroll continued to struggle and was released after pitching just 18 innings.

Carroll attempted two unsuccessful comebacks in the next three years. Vern Rapp, the most influential coach in his career, was in his second year as skipper of the St. Louis Cardinals and arranged an invitation to the team’s minor-league spring-training camp in 1978. “I just called and told him that I’d like to give it one more chance,” Carroll said, but he was not offered a contract. Out of baseball entirely in 1979, a healthy and physically fit Carroll thought a year’s rest might rejuvenate his sore arm and signed a contract in 1980 with the Alexandria (Virginia) Dukes of the Single-A Carolina League, a team without a major-league affiliation. “I was 27 and wasn’t sure what I wanted to do. Baseball is a great magnet especially when you’ve grown up with it and it’s been your life. It’s hard to break away,” he said. After 17 innings, he realized that it was time to move on and retired from baseball.36

In parts of two seasons with the Cincinnati Reds, Carroll won eight games and lost four while posting a 4.16 ERA in 125⅓ innings. In the minors he was 66-56 with a 3.96 ERA.

Carroll has had a successful career with MITRE, a not-for-profit, federally funded research and development center where he has served as an analyst and department chief engineer. In 2012 he was managing the Financial Integrity Division, leading MITRE work programs for the Treasury Department, the Federal Reserve Board and financial regulators. But the transition to life away from baseball was not easy for him. “It took a while to find my way as far as a post-baseball career, but I did,” he said. “I am fortunate to be in work that is as exciting as baseball.”37 With an M.A. in international affairs from Georgetown University, since 2008 Carroll has also been an adjunct professor in the Georgetown University School of Foreign Service, where he teaches courses on international security.38

Carroll and his wife, Elizabeth, resided with their two sons in Hamilton, Virginia, in 2021. Carroll enjoyed occasionally coaching in youth leagues and speaking to teams. He credited baseball for his success in his post-playing career by teaching him to work in teams, deal with pressure, and come to terms with the everyday grind.

Last revised: January 21, 2021 (ghw)

This biography is included in the book “The Great Eight: The 1975 Cincinnati Reds” (University of Nebraska Press, 2014), edited by Mark Armour. For more information, or to purchase the book from University of Nebraska Press, click here.

Notes

1 Tom Carroll, interview with author, June 1, 2012. The author would like to express his gratitude to Tom, who alsoprovided additional information via email.

2 Carroll, interview.

3 Carroll, interview.

4 Carroll, interview.

5 Carroll, interview.

6 Carroll, interview.

7 Carroll, interview.

8 Carroll, interview.

9 The Sporting News, November 27, 1971, 51.

10 Carroll, interview.

11 Carroll, interview.

12 Carroll, interview.

13 The Sporting News, June 28, 1973, 45.

14 Carroll, interview.

15 The Sporting News, September 1, 1973, 30.

16 Carroll, interview.

17 The Sporting News, October 13, 1973, 28.

18 The Sporting News, November 17, 1973, 39.

19 Carroll, interview.

20 Carroll, interview.

21 The Sporting News, June 8, 1974, 34.

22 Carroll, interview.

23 “Studies Wait for Reds’ Tom Carroll,” Associated Press, in Bangor (Maine) Daily News, August 7, 1974, 26.

24 The Sporting News, August 17, 1974, 29.

25 The Sporting News, August 31, 1974, 24.

26 “Studies Wait for Reds’ Tom Carroll,” Associated Press.

27 Carroll, interview.

28 Carroll, interview.

29 Carroll, interview.

30 Carroll, interview.

31 Carroll, interview.

32 The Sporting News, December 25, 1976, 35.

33 Brodie Snyder, “Expos Take Draft Gamble on Young Pitcher,” Montreal Gazette, December 7, 1976, 4.

34 Carroll, interview.

35 Carroll, interview.

36 Carroll, interview.

37 Carroll, interview.

Full Name

Thomas Michael Carroll

Born

November 5, 1952 at Oriskany, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.