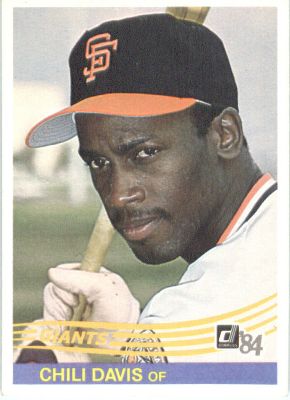

Chili Davis

Baseball has yet to take firm hold in the island of Jamaica, even though it is surrounded by other nations with a strong tradition in the sport. As the 2018 season ended, four men of Jamaican birth have made it to the majors, all of whom learned the game in the United States. The first and most successful of these players was Charles “Chili” Davis, who hit 350 home runs for five teams from 1981 to 1999. That is still the seventh-highest career total for switch-hitters, behind Mickey Mantle, Eddie Murray, Chipper Jones, Carlos Beltrán, Mark Teixeira, and Lance Berkman.

Baseball has yet to take firm hold in the island of Jamaica, even though it is surrounded by other nations with a strong tradition in the sport. As the 2018 season ended, four men of Jamaican birth have made it to the majors, all of whom learned the game in the United States. The first and most successful of these players was Charles “Chili” Davis, who hit 350 home runs for five teams from 1981 to 1999. That is still the seventh-highest career total for switch-hitters, behind Mickey Mantle, Eddie Murray, Chipper Jones, Carlos Beltrán, Mark Teixeira, and Lance Berkman.

Over his 19 seasons, Chili also earned a reputation as “smart, affable, and candid.”[1] He developed into a leader with a calming influence and a philosophical bent. A line of his has been quoted widely: “Growing old is mandatory; growing up is optional.” In addition, Davis has become a well-regarded hitting coach.

Charles Theodore Davis was born on January 17, 1960, in Jamaica’s capital city, Kingston. His parents were William and Jenny (Baux) Davis.[2] There were four other children in the family, three boys and one girl.[3]

The second and third Jamaican-born big-leaguers – Devon White and Rolando Roomes – both played cricket as young boys. (The fourth, pitcher Justin Masterson, moved when he was two years old and did not have Jamaican roots.[4]) Although it remains unconfirmed whether Davis also played cricket in his youth, it seems likely. At least one report showed him playing baseball’s relative in the Cayman Islands after his retirement.[5]

Yet while cricket was well entrenched in Jamaica, a British possession until 1962, baseball was visible — if only on the fringes. The first baseball game played on Jamaican soil took place in November 1905, between teams from the United States cruisers Denver and Yankee. The New York Times reported that “a large and enthusiastic crowd” watched the game.[6] The early 1930s saw baseball in vogue. Kingston’s newspaper, the Daily Gleaner, carried quite a few stories about club teams. In addition, the Jamaica Baseball Association was founded at this time; it remained sporadically visible thereafter. In the 1960s, future big-leaguer Wenty Ford came from his native Bahamas at least three times to play against Jamaican teams, as the Gleaner reported.[7]

When Bahamian cricket player André Rodgers came to the U.S. in the 1950s and made the majors, his success spurred baseball’s popularity in his homeland. The Bahamas sent five homegrown players to the majors between 1957 and 1983, plus quite a few more minor-leaguers. Yet despite the enduring success of Davis and Devon White, it didn’t turn out that way in Jamaica.

White, who was born almost three years after Davis, moved from Kingston to New York City at the age of nine. That was the first time he picked up a baseball bat and glove. Baseball was his fourth sport; growing up, Devon played cricket and soccer.[8] Rolando Roomes was also born in 1962. He too played cricket as a small boy with his brothers on the Army base in Kingston – but his family moved to Brooklyn in 1969, whereupon Roomes started to play stickball and baseball.[9]

The Davis family moved in 1970, after the dentist for whom mother Jenny worked transferred his practice.[10] They went not to New York but to Los Angeles. A 1991 story said, “His memories of the time are hazy, or at least that is the way Davis prefers to describe them. He says he recalls being lost briefly in the Miami airport, being teased because of his accent by the children in his new neighborhood and spending most of his first Little League season on the bench.”[11] Meanwhile, his parents supported the family as “factory workers pretty much.”[12]

“I played baseball when I came to the United States because I absolutely fell in love with that game,” Chili told Yankees Magazine in its November 2008 issue. “I’ve never fallen in love with anything else, I mean, besides my kids. It was so fascinating to me – a kid that grew up in Jamaica, that never played baseball, didn’t even hear of baseball, didn’t know who Babe Ruth, Hank Aaron, Willie Mays [were], none of those guys when I came to the States. And the first time I saw that game played, I went, ‘Wow, I want to do that.’” [13]

Chili got his nickname at the age of 12. As he told the story himself in 1982, “My dad gave me a haircut…and it wasn’t a very good one. When I went out of the house, my friends got on my case and said it looked like someone put a chili bowl over my head and cut around it.”[14] One friend in particular coined it, Shawn Shephard – a cousin of Shane Mack, Chili’s future teammate with the Minnesota Twins.[15] Although the “Bowl” part dropped away over time, “Chili” stuck for good. Davis himself wound up becoming a barber on the side. In 1985 he said, “I like playing with hair…it’s a hobby, I guess.”[16]

“I was pretty rebellious when I was younger,” Chili said in 1982. “I could’ve turned out to be a gangster or a drug addict if my family didn’t get on me. I got a lot of whippings. I guess they were worthwhile but I hated them at the time. I thought my parents were trying to kill me. I got whipped with belts, shoes, whatever. My uncle once beat me with a fan belt from a car.”[17]

Baseball helped keep him out of trouble. Davis played catcher, first at Fremont High School and then at Dorsey High, from which he graduated in 1977. At least ten other men have gone from Dorsey to the majors, including Sparky Anderson and the brothers René and Marcel Lachemann. Two other good African-American big-leaguers, Don Buford and Derrel Thomas, went there too.

In Chili’s youth, Los Angeles was still a mine of black baseball talent. High-school opponents included Darryl Strawberry (Crenshaw High) and Eric Davis (two years behind Chili at Fremont). George Genovese of the San Francisco Giants, whose brother Frank “Chick” Genovese was also a notable scout, was watching. The Giants drafted Davis in the 11th round of the June 1977 amateur draft. As Genovese recalled, though, he had a hard time convincing the Jamaican parents that their son could make money in baseball. They were skeptical about why a team would pay a bonus.[18]

With encouragement from Genovese, and the agreement of hitting coach Hank Sauer, the natural righty turned to switch-hitting for the first time in Instructional League that fall. He had wanted to try it at Dorsey, but his coach there did not want him experimenting while the team was doing well.[19] A 1997 feature added, “[Davis] quickly tired of seeing inside sliders from right-handed hitters. ‘So one day I went out and told Hank Sauer that I was going to switch hit. If I can’t hit it out from the left side, I’m not going to do it because I’m not going to be a singles hitter from one side and a power hitter from the other…I hit .343 that year in instructional ball. The first home run I hit left-handed was unbelievable. Boom!”[20]

Davis made it to the majors after two seasons in Class A ball and a third in Double A. He still caught a fair amount early on but made the transition to the outfield. Thanks to his torrid hitting in spring training 1981, he jumped from Shreveport to the San Francisco roster. Manager Frank Robinson said in 1983, “I liked Chili from the start because you could see he was a natural. I liked everything about him. He had all the tools and carried himself well. Before he played a major league game, I knew he was the best center fielder we had in camp. His arm was strong and accurate, and he did things instinctively. I had no doubts about him as a hitter, either, because being a switch-hitter is a tremendous advantage.”[21]

The rookie’s big-league debut came in the Giants’ second game of the ’81 season. It’s worth noting that men of Jamaican descent had probably appeared in the majors before – though they were born in other nations. In the 19th century, many Jamaicans went to Panama to work on the Canal, railroads, and banana plantations. Several Panamanian big-leaguers have had English surnames, though the families of some of these men may also have come from other British West Indian possessions such as Barbados.[22] Other players with one or more Jamaican grandparents followed Davis, such as David Green from Nicaragua and Aroldis Chapman from Cuba. Others may have preceded Chapman — for example, Tony Taylor‘s father was apparently Jamaican — since Cuba received nearly 100,000 immigrants from Jamaica between 1902 and 1925 alone.[23] One saying goes that for every Jamaican on the island, there’s another in a different country.

Chili appeared in eight games for San Francisco in April and early May before he was sent down. He spent the remainder of the 1981 season with Triple-A Phoenix (.350-19-75, with 40 stolen bases). Except for 10 more games with Phoenix in 1983 and injury rehab in 1998, he would never play in the minors again.

In the winter of 1981-82, Davis played winter ball in Puerto Rico, helping the Ponce Leones win the league championship. He returned for the 1983-84 season. Chili later told author Tom Van Hyning, chronicler of the Puerto Rican Winter League, “I had a lot of fun playing in Puerto Rico. I’ve been back during the holiday season to visit friends I made in Ponce.”[24] After that second season, though, it appears that he preferred to rest and relax during his off-seasons.

Davis came in fourth in the voting for National League Rookie of the Year in 1982. He said that year, “I was a star in high school and the minors. We played merely on talent.” He added that he had improved and matured with the help of the Giants’ patient coaches. “I’ve learned to play team baseball instead of individual baseball.”[25] Another prime influence was veteran second baseman Joe Morgan. In 1998, Morgan said, “Of all the guys in baseball I’ve quote, unquote ‘raised,’ the one I’m most proud of is Chili Davis.”[26]

Since San Francisco then had Jack Clark in right field, Chili played center field; as a result, he was saddled with comparisons to Willie Mays. He became a corner outfielder after the arrival of Dan Gladden. Ankle injuries (including one that needed surgery after his rookie year) also diminished what was originally good speed. In his early years, Davis batted leadoff frequently, but his stolen-base percentage was rather low. He struck out a fair amount, though not excessively by today’s standards, yet also developed a good eye for walks.

Although he had four homers in his first four games of 1983, the sophomore jinx bit Davis (.233-11-59). He was still hitting over .300 in mid-May but then went into a severe drought. Frank Robinson temporarily demoted him to Phoenix to try to snap him out of the slump.[27] The second half wasn’t much better, but Chili returned to form in 1984, becoming a National League All-Star. He was named to the NL squad again in 1986.

Chili credited hitting coach Tom McCraw, who was with the Giants from 1983 through 1985, for his approach at the plate. “Davis said that McCraw told him, ‘Never leave a fastball. You always look for the fastball. And if there are two strikes, go right back to the fastball and adjust to something else, because you can’t hit a fastball looking for a curveball, but you can hit a curveball looking for a fastball.’”[28]

Chili never liked playing the outfield in Candlestick Park, with all its unpredictable vortices of wind.[29] He also was not happy with the Giants’ general lack of success. The only time they got to the playoffs in his time there was 1987. In addition, that year he faced a major distraction: a palimony suit from the mother of his son, Charles T. Davis II. He later said that he felt like he’d overstayed his welcome.[30] As a result, Davis signed as a free agent with the California Angels following that season.

With the Angels, Davis remained a full-time outfielder in 1988 and 1989. He flanked his fellow Jamaican, center fielder Devon White, and stood godfather to White’s daughter. However, 1990 was the last time he got any significant time in the field. For the remainder of his career, he was almost exclusively a designated hitter.

The Angels didn’t make it to the playoffs in any of those three seasons, and so Chili joined the Minnesota Twins as a free agent in 1991. He won his first World Series ring that year. Star center fielder Kirby Puckett is remembered for saying ahead of Game Six, “Jump on board, boys! I’m going to carry us tonight.” Even so, looking at the whole season, “some Twins observers [said] Chili Davis was more valuable, and Puckett perpetuated that talk by saying Davis sometimes carried the club.”[31] In the Series, Chili hit .222 but connected for homers off Tom Glavine in Game Two and Alejandro Peña in Game Three.

Although he liked Minneapolis, the Midwestern cold didn’t agree with his Caribbean blood. After 1992, Davis tested the free-agent waters again. He returned to the Angels on a one-year deal but wound up there for four seasons altogether. He set a career high in RBIs with 112 in 1993 — but the strike year, 1994, was shaping up to be his best. When the season came to its premature end, Chili had 26 homers and 84 RBIs in 108 games. He followed up with a career-high .318 batting average in 1995, though that season also featured an unfortunate incident that cost him a $5,000 fine. The normally pleasant and even-tempered player went over to the stands and poked a fan in the face. The man said that he wasn’t even the one whose heckling had riled Davis. He filed suit in 1996, though lack of further stories suggests an out-of-court settlement.

Following the 1996 season, Anaheim (as the team was then known) traded Davis to Kansas City for Mike Bovee and Mark Gubicza. In his only season with the Royals, the 37-year-old vet set his career high with 30 home runs. He also drove in 90 runs for the sixth time, while setting a positive example for other players. Although Jay Bell had already been in the majors since 1986, and he too spent only 1997 in Kansas City, he later called Davis the player he had learned most from. The previous year, Angels teammate Tim Salmon said the same thing, noting of Chili, “He’s a true professional.”[32]

Yet again, though, Davis became a free agent. In December 1997, he signed with the New York Yankees. Owner George Steinbrenner admired Chili and wanted him on the team, calling him “a tremendous hitter and a tremendous influence in the clubhouse.”[33] In fact, as Derek Jeter observed, The Boss later put up a sign outside the clubhouse at the team’s spring training site, Legends Field. “[It] read, ‘Unless you’re the lead dog, the view never changes,’ which is a saying that Chili Davis used to have on his T-shirt.”[34] This was just one of many slogan-bearing T-shirts that “Chili Dawg” made up; the popular items had been a sideline of his since Minnesota.

“When I became a Yankee in ’98,” Davis recalled a decade later, “the mentoring was done. Here I am in a professional organization, with a history of winning, with a tradition of winning and with quality players that, even though they were young, were establishing themselves as prime players. I wish that the Yankees years as a player had been a lot longer than just two years. I wish that it had been a five-, six-, seven-, 10-year period to really experience that.” [35]

The Yankees had won the World Series in 1996, and with Davis aboard, they won the next two of their three consecutive World Championships. In the second game of the 1998 season, he injured his ankle while sliding into second at Anaheim. Surgery to repair a tendon was required, keeping him out of the New York lineup until mid-August. Yet Chili was optimistic, saying, “I’ve got one of those Jamaican bodies. Things usually heal right for us!”[36]

Indeed, when colon cancer sidelined Darryl Strawberry just ahead of the playoffs, Chili provided key hits and leadership.[37] That October, after a big game against Cleveland in the ALCS, he remarked, “There are certain things I can’t do, certain pitches I can’t hit. You stay away from them. You try to wait for pitches you can hit. The bat speed isn’t what it used to be. You make up for it by using your head, working counts, getting ahead in counts and getting pitches to hit and hitting them hard.”[38]

Davis enjoyed a solid last season with New York in 1999. He had spoken openly about retirement and wanted to be in top physical condition for his last run.[39] In addition to his production with the bat, Chili was still great at keeping the team loose. Ten years later, David Cone told a story about his perfect game of July 18, 1999.

“[In the fifth inning], Nobody was there to warm me up, so Chili grabbed a glove and squatted, with that big body of Chili’s. I was just lobbing it in there until [Joe] Girardi got out there. In between innings, Chili came to me and said: ‘You know, I used to catch in the minor leagues. I could catch your [stuff].’ Just something like that really made me laugh, and that’s all I needed. Chili was my guy.”[40]

Upon Davis’ retirement in December 1999, Yankees general manager Brian Cashman said, “Chili exemplifies character and class. He was a veteran leader who, along with his offensive skills, brought professionalism and competitiveness to the ballpark every day.”[41]

“I got to put on the pinstripes, I got to sit in the Yankee clubhouse, and I got to play as a Yankee,” Davis said. “And the thing that never left was the urgency to perform. You don’t get to wear this uniform and be a part of this here and not perform.”[42]

Five years later, Chili was on the Hall of Fame ballot. His career has received due consideration of whether it merited induction at Cooperstown, and though he was “one and done” after getting just three votes in 2005, his achievements were substantial. Perhaps his most interesting career stat is that he homered from each side of the plate in the same game 11 times. At the time he retired Davis was tied with Eddie Murray – the hitter he admired most[43] –at the top of this list.

Chili received consideration for a minor-league managing job with the Yankees in 2002 and was a rumored candidate to become hitting coach with the big club after the 2003 season. Instead, from 2003 through 2005, he was hitting coach with the Major League Baseball Australian Academy, tutoring students from France, Korea, Japan, China, New Zealand, and other nations along with fellow Yankee alumni Graeme Lloyd and Pat Kelly. He had first gone Down Under years before, since he always enjoyed traveling in the off-season. Along with Australia, another favorite spot was Bali.[44]

Chili then established Chili Davis Premier Baseball Club, a training facility in Peoria, Arizona (not far from his home). The desire to get involved with pro ball resurfaced, though, and he interviewed for several coaching positions. In October 2010, he became a hitting instructor for the Dodgers in the Arizona Instructional League. There was talk that he might become L.A.’s hitting coach.[45] He also received consideration as manager of the Pawtucket Red Sox, Boston’s top farm club; in January 2011, he became hitting coach for the PawSox.[46]

“My belief is that when you’re a good instructor, first and foremost, you have to get your students to believe that they can do the right things,” Davis said of his coaching work. “If they don’t believe they can be a good hitter, they’re not going to be. Eliminate the fear factor with them, the fear of striking out, the fear of making a mistake, and try to get them to go more toward trying to succeed.”[47]

Past the age of 50, Davis was still a single man. Back in 1996, he talked about this with Orange Coast magazine. “Years ago, Chili Davis made a wager with his teammate, Bill Laskey, on who would marry first. ‘Needless to say, I lost.’” He added, “I’m very leery because there are some women who just want to be Mrs. Chili Davis…Women express their feelings to me much faster than I do toward them.”[48] Another relationship in the early 2000s had unhappy repercussions. Following lurid allegations in civil court, the jury ruled in April 2006 that Davis had to pay $350,000 for various claims.[49] Counter-actions related to the woman’s dealings with the house they had shared dragged on for years.

Chili continued to feel a connection to his native land and other Jamaican-born players. One was Andrew “Dee” Dixon, who played in the minors from 1986 to 1990, as well as Mexico and Venezuela. Dixon moved to Poughkeepsie, New York at age ten and learned baseball a couple of years later after the neighborhood kids teased him. The Giants made the speedy outfielder their 17th-round draft choice in 1986, and he became good friends with Davis. Another was Goefrey (pronounced GOFF-ree) Tomlinson, who moved to Texas at age 11 and went to the University of Houston. Goef became the fourth-round pick of the Royals in 1997; “Davis helped bring Tomlinson into the Royals’ fold.”[50] The outfielder reached Triple A in 2000 and remained in indie-league ball as late as 2011.

Efforts to plant baseball more deeply in Jamaica itself have continued. One such movement started in 1991, when two men from the Toronto area started the Jamaican Youth Baseball Camp. They received backing from the International Baseball Association, and the New York Mets also donated equipment.[51] It’s notable that Devon White was then the starting center fielder for the Toronto Blue Jays. One of the camp’s founders, Leon Taylor, came from Kingston. In 2007 he was an associate scout for the Pittsburgh Pirates.[52] He later became an international consultant for the Los Angeles Dodgers and continued to develop baseball in Jamaica, as well as other places including Bermuda.[53] As of 2013 he was the hitting coach for the Oakland A’s.

On another front, Andrew Dixon helped achieve a milestone. In March 2010, Major League Baseball’s manager of international baseball operations for Latin America, Renaldo Peralta, joined Sport Minister Olivia Grange in announcing MLB’s offer to assist in building a baseball field at the Trelawny Multi-Purpose Stadium on the island’s north shore, east of Montego Bay. Peralta said, “We’re most certain that it won’t be our last time here. The support from the Jamaican Government brings excitement. We want to totally help develop the game and present the youths of Jamaica with new opportunities.”[54]

Dixon said in April 2010, “Baseball is not part of Jamaican culture but it’s similar to cricket. All I say is as a Jamaican we can learn any sport. There is no stopping us once we put our minds to it.” Andrew hasn’t spoken with his friend Chili Davis in some time, but given Chili’s international mindset, conceivably he may yet lend his prominent name and professional skills. He takes pride in Jamaica, and vice versa. It would surely mean a great deal to him and the nation to see a Jamaican-raised player make it to the top.

Davis served as hitting coach for the Oakland A’s for three seasons from 2012 through 2014. He then occupied that same role for the Boston Red Sox from 2015 through 2017 and for the Chicago Cubs in 2018. In November 2018, the New York Mets named him their hitting coach. He remained in that position until being relieved on May 3, 2021. To date, Davis has not returned to hte majors.

First published in January 2011. Last updated on August 6, 2023.

Thanks to Andrew Dixon.

Sources

www.baseball-reference.com

www.retrosheet.org

www.thebaseballcube.com

www.newspaperarchive.com

www.jamaicanbaseball.com

www.andrewdixonfoundation.org

Yankees Magazine, Volume 29, No. 8, November 2008

[1] Curry, Jack. “Designated, Dominant, Delightful: It’s Davis.” New York Times, April 27, 1999.

[2] Evers, John L. “Chili Davis.” Entry in Latino and African American Athletes Today (David L. Porter, editor). Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2004: 71.

[3] “Words flow easily – but infrequently – from Chili Davis.” Minneapolis Star-Tribune, October 6, 1991.

[4] Miguel, Tim. “Long Journey Brings Masterson To San Diego State.” CBS College Sports website, February 23, 2006 (http://www.cstv.com/sports/m-basebl/stories/022306act.html). Justin’s father was serving for three years as Dean of Students at Jamaica Theological Seminary, where he had once been a foreign exchange student. “My Interview With Justin Masterson, Part I.” Sox1fan.com website, February 16, 2009.

[5] Brush, Daniel J., David Horne and Marc CB Maxwell. Major League Baseball: An Interactive Guide to the World of Sports. New York, NY: Savas Beatie LLC, 2009: 175.

[6] “First Baseball Game in Jamaica.” New York Times, November 3, 1905.

[7] For detail, see Wenty Ford’s biography on the SABR BioProject.

[8] Penner, Mike. “The Project.” Los Angeles Times, March 16, 1987: Sports-6. DiManno, Rosie. “Everyone else remembers The Catch. Devon White remembers The Miss.” Toronto Star, October 16, 1993: D3.

[9] “Cricket groomed Roomes for Reds.” Spokane Chronicle, May 29, 1989.

[10] “He’s no Angel.” Minneapolis Star-Tribune, April 14, 1991.

[11] “Words flow easily – but infrequently – from Chili Davis”

[12] Kernan, Kevin. “Bombers Are a Father-Son Team.” New York Post, October 30, 1999.

[13] Lindbergh, Ben. “Southwestern Chili Entrée,” Yankees Magazine, Volume 29, No. 8, November 2008.

[14] “Rookies.” The Sporting News, July 5, 1982: 14.

[15] Botte, Peter. “Chili Hot for Boss.” New York Daily News, December 12, 1997.

[16] “Chili’s a Cut Above — Davis Also Makes Good Moves with Scissors.” Sacramento Bee, June 23, 1985: C8.

[17] Wilstein, Steve. Associated Press, May 18, 1982. This story received various titles across different newspapers.

[18] Atlanta Journal, December 4, 1988: D4. Keown, Tim. “Major League Baseball Scouts Still Have a Place in the Sun.” Los Angeles Times, April 1, 1990.

[19] Peters, Nick. “Switch-Hitter Chili Giants’ Latest Slugger.” The Sporting News, May 16, 1983: 57.

[20] Kaegel, Dick. “Chili Davis Keeps Climbing on Switch-Hitter Charts.” Baseball Digest, June 1997: 65. “Professional hit man: New Royals DH Davis remains one dangerous batter.” Kansas City Star, February 24, 1997: C1.

[21] Peters, op. cit.

[22] Pat Scantlebury is one confirmed example of Barbadian descent. This area bears further investigation.

[23] Moya Pons, Frank. History of the Caribbean. Princeton, New Jersey: Markus Wiener Publishers, 2007: 302.

[24] Van Hyning, Thomas E. Puerto Rico’s Winter League. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 1995: 160.

[25] Wilstein, op. cit.

[26] Lupica, Mike. “Chili Starting to Get Hot.” New York Daily News, October 14, 1998.

[27] Peters, Nick. “A 10-Day Demotion For Slumping Chili.” The Sporting News, July 11, 1983: 17-18.

[28] Draper, Rich. “Chili spices up Hall ballot.” Mlb.com website, December 30, 2004 (http://minnesota.twins.mlb.com/news/article.jsp?ymd=20041230&content_id=926395&vkey=news_min&fext=.jsp&c_id=min)

[29] Wilstein, op. cit.

[30] “Fresnan Sues Chili for Palimony.” Fresno Bee, May 1, 1987. Peters, Nick. “Chili grudgingly grants interview.” McClatchy News Service, March 10, 1988.

[31] Heyman, Jon. “Kirby Puckett: A Star Who Doesn’t Act Like One.” Baseball Digest, February 1992: 25.

[32] Sorci, Rick. “Baseball Profile: Outfielder Tim Salmon.” Baseball Digest, October 1996: 67. Sorci, Rick. “Baseball Profile: Jay Bell.” Baseball Digest, October 2000: 35.

[33] Curry, Jack. “Yankees Get Their D.H. By Signing Chili Davis.” New York Times, December 11, 1997.

[34] Jeter, Derek and Jack Curry. The Life You Imagine. New York, NY: Three Rivers Press, 2000: 173.

[35] Lindbergh, op. cit.

[36] Lennon, David. “Chili’s 2nd Thoughts.” Newsday, April 25, 1998: A44.

[37] Lupica, op. cit.

[38] Chass, Murray. “On Baseball: Davis Produces as Designated Hitter.” New York Times, October 12, 1998.

[39] Curry, op. cit.

[40] Kepner, Tyler. “Cone’s Magic Moment, 10 Years Later.” New York Times, July 18, 2009.

[41] Associated Press, December 2, 1999.

[42] Lindbergh, op. cit.

[43] Kaegel, op. cit.

[44] Tetrault, Sharon. “The Independents.” Orange Coast, June 1996: 78.

[45] Gurnick, Ken. “Davis joins Dodgers as an instructor.” Mlb.com website, October 14, 2010 (http://mlb.mlb.com/news/article.jsp?ymd=20101014&content_id=15634814&vkey=news_la&c_id=la&partnerId=rss_la)

[46] Mullen, Maureen. “Sox may hire Gedman, Davis.” Necn.com website, December 22, 2010 (http://www.necn.com/12/22/10/Sources-Gedman-Davis-leading-candidates-/landing_sports.html?blockID=378585&feedID=3352)

[47] Lindbergh, op. cit.

[48] Tetrault, op. cit.

[49] Kiefer, Michael. “Chili Davis to Pay $350K for Assault Claims in Civil Case.” Arizona Republic, April 7, 2006: C15.

[50] Boyce, David. “Davis helped KC sign Tomlinson.” Kansas City Star, August 24, 1998.

[51] “Scouting for baseball talent in Jamaica.” Toronto Star, February 7, 1991. Reid, Jim. “Metro men bring baseball to children in Jamaica.” Toronto Star, March 26, 1992.

[52] Braziller, Zachary. “International pastime?” Queens (New York) Courier, August 23, 2007.

[53] “Dodgers make a pitch for Bermuda’s players.” Royal Gazette (Hamilton, Bermuda), March 5, 2010.

[54] “MLB to assist with field at Trelawny Stadium.” Jamaica Observer, March 5, 2010.

Full Name

Charles Theodore Davis

Born

January 17, 1960 at Kingston, Kingston (Jamaica)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.