Lance Berkman

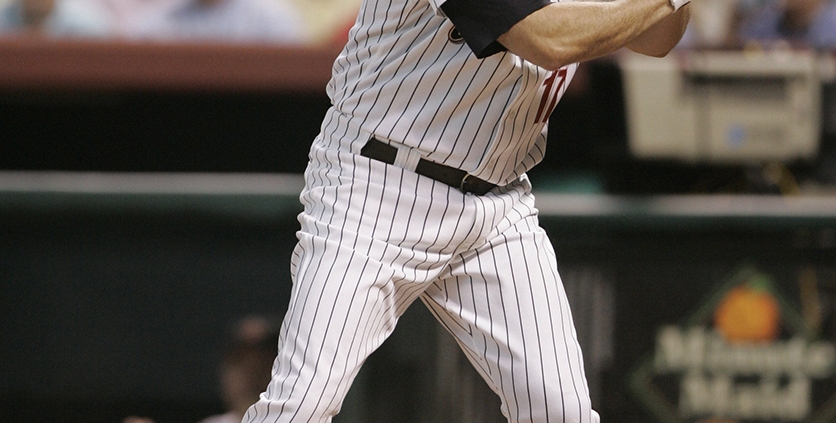

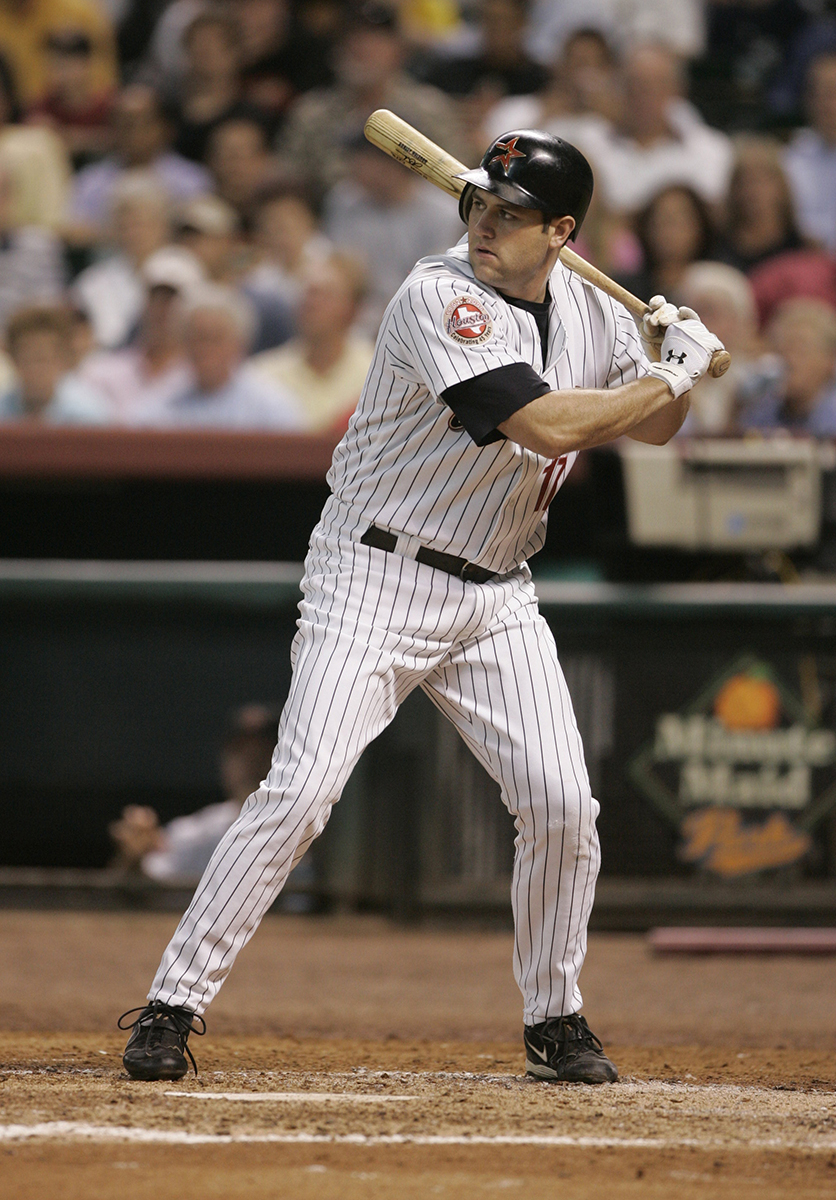

Born February 10, 1976, in Waco, Texas, William Lance Berkman is best known as one of the Houston Astros “Killer B’s.” From 1999 through 2005, Berkman teamed with Hall of Famers Jeff Bagwell and Craig Biggio to form one of the best offensive trios in the National League.

Berkman was one of the greatest switch-hitters of all time, second only to Mickey Mantle in lifetime on-base percentage, slugging percentage, On Base Plus Slugging (OPS),1 and OPS+.2

In the 10 seasons from 2000 through 2009, Berkman hit 309 home runs and produced a slash line of .300/.413/.559/.972.3 His totals during that span placed him in the top 10 in the majors in walks, doubles, home runs, RBIs, on-base percentage, and OPS. Berkman was named to the National League All-Star Team six times and finished in the top 10 in voting for Most Valuable Player six times. His career OPS of .943 ranks 22nd all-time,4 just behind Ty Cobb and just ahead of Willie Mays.

A switch-hitter and left-handed thrower, Berkman spent 15 years in the major leagues, from 1999 through 2013. He played parts of 12 seasons with the Astros before finishing his career with the New York Yankees, St. Louis Cardinals, and Texas Rangers. His primary positions were outfield, where he played all three spots, and first base.

Berkman’s parents are Cynthia, an elementary school teacher, and Larry Berkman, an attorney. Both had athletic backgrounds. Cynthia was a high-school sprinter on the varsity track team and Larry played baseball at the University of Texas.5 The Berkmans also had two daughters, Jennifer and Brooke. He married Cara, the sister of a college teammate. They have four daughters.6

One of Larry’s priorities was teaching Lance to hit. Lance said, “Ever since I could walk, I’ve had a bat in my hand.”7 From the time Lance played in his first youth league, Larry insisted that he switch-hit. (He was a natural right-handed hitter.) Until Lance reached high school, Larry required him to alternate at-bats from each side of the plate, regardless of the pitcher or game situation. “When things were tight and my team needed a run, my teammates used to beg me to hit right-handed,” Lance said. “But my dad wouldn’t allow it. He made sure I learned to switch-hit.”8

Berkman spent most of his youth in Austin, Texas, and attended Austin High in 1991 and 1992.9 When he was a junior, his family moved to New Braunfels, Texas, where Berkman was an honor student and a star for the Canyon High School baseball team.10 As a senior in 1994, Berkman batted .539 with a slugging percentage of .974. He banged eight homers, drove in 30 runs and made the 28-4A All District First Team.11 Canyon High retired his number in 2002.12

When Rice University offered Berkman a scholarship early in his senior year, he agreed based on his father’s advice. “I wanted Lance to be able to relax and enjoy his senior season in high school,” said Larry.13

As a freshman at Rice, Berkman hit .328, set the national record for doubles in a season, and was named Southwest Conference Newcomer of the Year.14 Later that summer, he was voted Most Valuable Player of the 61st National Baseball Congress World Series, in which he tied the tournament record with 25 RBIs in eight games.15

In 1996, his sophomore season, Berkman hit six homers in a doubleheader and nine in one week. Lou Pavailich, editor of Collegiate Baseball magazine, reported that in 26 years of keeping statistics, he had never heard of a player hitting that many home runs in a week.16

That same year Berkman set Rice single-season records for home runs, RBIs, total bases, and slugging percentage. His .398 batting average was the third-highest in school history.17 He also ranked in the top 10 in the conference in runs scored, walks, and on-base percentage.18 He was chosen to the All-SWC First Team.19 Berkman spent his summer in Massachusetts, where he led the Cape Cod League with a batting average of .358.20

In 1996 Rice joined the Western Athletic Conference and in 1997, Berkman’s junior year, the Owls finished 47-14 overall and 20-9 in the WAC. The team again went to the NCAA Division I Tournament and won the Central Regional title.21 Berkman was named the tournament MVP.22 That earned the Owls their first-ever trip to the College World Series,23 where they were eliminated in the first round.

Berkman led the NCAA with 41 home runs and 134 RBIs and batted .431. At the time, the 41 homers were third in NCAA history and the 134 RBIs, second. He averaged 2.13 RBIs per game, breaking an NCAA record that had stood since 1959.24 He also set Rice records for career batting average, doubles, RBIs, home runs, total bases, and slugging percentage.25 He capped his dream season by being named NCAA Player of the Year by the National Collegiate Baseball Writers Association.26

Berkman’s commitment to religion solidified while he was in college. “I had a buddy who was a strong Christian and lived his life in accordance with that,” he said. “This guy was different, and the more that I was around him, I realized that I was a guy who claimed to be a Christian, yet my life didn’t look any different from someone who didn’t. That was my Damascus road experience, where God said either you’re in or you’re out. If you’re going to claim to be a Christian, you’d better demonstrate that. Otherwise, don’t even bother.”27

In 2015 Berkman’s conservative, Christian beliefs stirred controversy in the LGBTQ community when he opposed a Houston proposition that would have made it legal for transgender people to use public restrooms the opposite of their biological sex.28, 29

Berkman had long felt society’s morals were decaying. In 2008, he said, “There’s no absolute truth in our society anymore. Whatever you feel is right, well, do it. Well, that’s no way to live. Some say it’s fine to have premarital sex, it’s fine to get drunk, it’s fine to abuse women, it’s fine to cheat on your wife or on tests, it’s fine to live alternative lifestyles. There’s stuff that comes up with society all the time that’s eroding our moral fiber. And if you don’t take a stand now, you never will.”30

Berkman decided to forgo his senior year at Rice and, on June 3, 1997, the Houston Astros chose him with the 16th pick in the first round of the amateur draft. Soon after, he agreed to a contract that included a signing bonus of $1 million.31 “He is the best hitting prospect we have drafted in some time,” said Astros general manager Gerry Hunsicker. “A switch-hitter with power is a rare commodity you just can’t pass up.”32

The Astros assigned Berkman to the Class A Kissimmee Cobras (Florida State League).33 Although he usually played first base at Rice, the Astros switched Berkman to the outfield because they had future Hall of Famer Jeff Bagwell at first.34

Kissimmee manager John Tamargo said, “(Berkman)’s always at the park early; he works late. To him, it’s a job. They pay him to play, and he is trying to get the most out of it.”35 Berkman batted .293 for Kissimmee in 53 games, cracked 12 home runs, and had an OPS of .961.

In 1998 the Astros promoted Berkman to the Double-A Jackson (Mississippi) Generals for whom he belted 24 home runs, batted .306,36 and made the Texas League All-Star team.37 Late in the season Berkman was called up to the Triple-A New Orleans Zephyrs. He burst into the league, hitting three home runs in his first game.38 When New Orleans won the Triple-A World Series at season’s end, Berkman was named MVP.39

Berkman started the 1999 season in Triple A and on April 12 tore the meniscus in his left knee.40 After recovering from surgery, he was back in the lineup on May 14.41 Hitting .303 with eight home runs in 58 games, Berkman was called up to the major leagues on July 16, to replace the injured Carl Everett.42 Berkman said, “Ever since I was six years old, I wanted to be a professional ballplayer. Now, here I am in the big leagues. We’ll see how long it lasts.”43

Not very. When Everett recovered, Berkman was sent back to New Orleans,44 but he returned to Houston on August 13 and finished the season there. His major-league average was .237 with an OPS of .708 and four home runs in 34 games.

Although Berkman led the Astros with seven home runs in spring training of 2000, again he began the season at Triple A. A hot start, including a game in which he went 4-for-5 with three homers, and an injury to Moises Alou got Berkman promoted to Houston in late April.45 But after hitting only .222 in his first dozen games, he was sent down. Two weeks later, when Roger Cedeño went on the disabled list, he returned to the Astros permanently.46

In 114 games, Berkman hit .297 with 21 homers. Although he was denied rookie status due to a technicality,47 Berkman received one vote for Rookie of the Year, and his .949 OPS led all rookies who had 400 or more plate appearances.

In 2001 Berkman again tore up spring training, hitting .350 with three homers.48 “I don’t ever take anything for granted,” he said. “I wanted to come in this spring and prove that I belonged out there.”49

Belong he did and he showed it with a breakout year. He led the major leagues with 55 doubles; since 1940, only two National Leaguers have hit more.50 Berkman finished in the top 10 in the majors in batting average, on-base percentage, slugging percentage, OPS, total bases, and extra-base hits. He had the highest batting average (.331) and OPS (1.051) of his career, drove in 126 runs, and scored 110. He cracked 34 home runs, becoming the first switch-hitter and 15th player to hit at least 50 doubles and 30 home runs in a major-league season.51 He made the All-Star Team and ranked fifth in voting for the NL MVP Award.

“Maybe five times this year, Lance has had what you’d call a bad at-bat,” said Astros manager

Larry Dierker. “Quite simply, he understands the art of hitting.”52

Even though the Astros lost nine of their final 12 games, they eked out the National League Central Division title with a record of 93-69. But they were swept in the Division Series by the Braves. Berkman’s performance was lackluster: He went 2-for-12, with two singles, and no walks, runs scored, or RBIs.

It was the fourth time in five years that the Astros won the division, but in the playoff series they won only two games. Dierker, the manager of each of those teams, was fired that offseason.53

In January of 2002, the Astros signed Berkman to a three-year contract worth $10.5 million even though he was not yet eligible for arbitration. General manager Hunsicker and owner Drayton McLane made the unusual move not only because of Berkman’s ability, but also because they were impressed by his contributions to the community. He established Berkman’s Bunch, which helped area children attend Astros games, and was a nominee for the Roberto Clemente Award for community service.54

Berkman justified his new contract by leading the NL with 128 RBIs and batting .292 with an on-base percentage of .405 and an OPS of .982. He hit 42 home runs and tied for third in the NL in total bases. He finished third in MVP voting and again was selected to the NL All-Star Team.

Berkman got off to a slow start in 2003. At the end of April he was batting only .208 with two home runs and four RBIs. That presaged a season in which Berkman underperformed by his standards. His OPS was the lowest since 1999, he hit only 25 home runs, and drove in fewer than 100 runs (93).

“This is the biggest struggle I’ve had in terms of driving in runs,” Berkman said. “I’m not hitting as many home runs this year and even though I’m swinging the bat good, especially in the second half, for whatever reason, I just can’t drive in runs.”55

The Astros held a 1½-game division lead on September 19. In Houston’s final nine games, Berkman hit .357 with an OPS of 1.149. Despite his hot streak, the Astros lost six of the nine and finished one game behind the Cubs and four games behind the Marlins for the wild card.

In his first three seasons, Berkman was a much better hitter from the left side than the right. That pattern would continue for his entire career. In 2003 Berkman briefly considered giving up batting right-handed and said that if he were to start his major-league career over, he would not switch-hit.56

In 2004 Berkman started the season 0-for-9, but from that point through the end of May, he batted .370 with an OPS of 1.248, hit 14 home runs, and drove in 42 runs. His torrid spring set the stage for a bounceback year, in which Berkman made his third All-Star Team, finished seventh in voting for the MVP, and had the highest on-base percentage of his career, .450.

That summer, the All-Star Game was played in Houston and Berkman entered the Home Run Derby. Although his home-run rate was much better batting left-handed, Berkman batted right-handed in the Derby. He felt he had more power from the right side and wanted to take advantage of the short left field in Minute Maid Park. He reached the finals, but lost to Miguel Tejada.57

On August 26 the Astros’ record was 64-63, seven games behind the Cubs for the wild card. From that point on, Houston went 28-7. The onslaught began with a 12-game winning streak, during which the Astros scored 109 runs. When they won 9 of their final 10 games, they earned the wild card by one game over the Giants.

In the Division Series, Houston beat Atlanta three games to two. The teams alternated wins before the Astros routed the Braves 12-3 in the deciding game. In the League Championship Series, the Astros led the Cardinals three games to two, but their season ended when they lost Games Six and Seven. In the two series, Berkman batted a combined .348, had an OPS of 1.110, hit four homers and drove in 12 runs.

On October 28, 2004, Berkman tore the anterior cruciate ligament in his right knee while playing flag football. He underwent surgery to repair the torn cartilage and reconstruct his ACL.58 Doctors estimated that Berkman could resume playing baseball in five to six months. He said, “I had no business being out there [playing football]. There’s no doubt about that. At the same time, we play football all the time in the offseason. I use that as part of just staying in shape.”59 Berkman was not under contract when he was injured.

To avoid arbitration, in January of 2005 Berkman signed a one-year contract worth $10.5 million. Less than two months later, he and the Astros agreed on a six-year deal that paid $10.5 million in 2005 and $14.5 million per year for the remaining five years. Berkman pledged $100,000 each season to the Astros in Action Foundation, which supports nonprofits and programs related to literacy, education, health issues, religious organizations, and reviving baseball in the inner city.60

Berkman returned from his knee injury on May 6. After 15 games, he was batting .173, with one home run and three RBIs. Berkman said, “I don’t have the same balance I’m used to having. I’ve hit a certain way for years and years, and now it’s a little weaker, and it’s throwing me off. Hopefully, it’ll improve the more I’m out there.”61

The knee did improve, and Berkman went on a two-month tear in which he batted .337 with an OPS of 1.034 and 40 RBIs and led the Astros to a record of 38-16 (.704). “I feel stronger,” Berkman said. “You always hear the term ‘midseason form.’ I feel like I’m getting into that. You’re not worried about your swing or your timing. You’re only worried about seeing the ball and hitting it.”62

The knee did improve, and Berkman went on a two-month tear in which he batted .337 with an OPS of 1.034 and 40 RBIs and led the Astros to a record of 38-16 (.704). “I feel stronger,” Berkman said. “You always hear the term ‘midseason form.’ I feel like I’m getting into that. You’re not worried about your swing or your timing. You’re only worried about seeing the ball and hitting it.”62

After losing their seventh straight game on May 24, the Astros had a record of 15-30 (.333). They were in last place in the division and had the second-worst record in the league. But Houston evidently experienced an epiphany, winning 74 and losing only 43 (.632) the rest of the season. The streak was highlighted by a 15-2 run from July 18 through August 3. Still, on September 13 the Astros remained behind the Marlins and Phillies for the wild card. Houston finished the season with a 13-5 run and beat the Phillies by one game. During the streak, Berkman batted .310 with an OPS of 1.074, hit five homers and drove in 16 runs.

After Game Three of the LDS, Houston led Atlanta two games to one. In the fourth game, with the Astros behind 6-1 in the bottom of the eighth, Berkman hit a grand slam. The Astros tied the game in the ninth, when Brad Ausmus homered with two outs, and finally won on Chris Burke‘s homer in the 18th inning.

Although the Cardinals beat the Astros for the division title by 11 games, Houston got revenge by eliminating St. Louis four games to two in the League Championship Series. In the Astros’ 44th season, they had reached their first World Series. They were swept by the White Sox. The Series was closer than the outcome indicated: Two games were decided by two runs and two by one run.

On January 23, 2006, Berkman had surgery on his right knee to remove scar tissue that had built up after the operation in November 2004. Though there had been some concern whether he would be ready, he was in the lineup on Opening Day.63

The surgery seemed to help as Berkman had one of his best seasons. He batted .315 with an OPS of 1.041 and reached career highs with 45 home runs (fourth in the NL) and 136 RBIs (third). He was again named to the All-Star Team and finished third in voting for the MVP. Berkman also ranked in the top 10 in the majors in on-base percentage, slugging percentage, OPS, home runs, RBIs, and WAR.

Berkman was often a comedian in the clubhouse, a guy who didn’t seem to take the game too seriously. To some, he didn’t take the game seriously enough. He didn’t have the body of a conditioned athlete; Gerry Hunsicker, by then the former general manager, described him as “lumpy.” Manager Phil Garner said, “Comparing him to some guys, he wasn’t (the hardest worker).”64

“I think (that perception) just comes from the fact that a lot of guys show up at two o’clock for a seven o’clock game,” Berkman said. “I don’t feel the need to do that. I get dressed right before (batting practice). To me, there’s no sense in getting loose before batting practice, then sit around for an hour and then get ready for the game.”65 “It works for him,” Garner said of Berkman’s approach. “You can’t argue with it. He’s totally off the wall. You can’t put a square peg in a round hole.”66

Berkman followed his excellent 2006 season with a 2007 season in which he posted his lowest batting average, on-base percentage, slugging percentage, and OPS since his rookie year of 1999. He did establish one career high, but that was in strikeouts.

“Everybody has a worst year of their career,” Berkman said. “Whether you realize it when you’re going through it or not, you can always look back at anybody’s career and pick out their worst year. I’m not conceding defeat and saying I’m not going to be able to rectify this year and finish up strong. That’s certainly going to be my ambition.”

“I’m frustrated when I come to the ballpark,” he said. “I want to win as badly as anybody, and I want to do well to help this team win and I care about it. I don’t want people to think I don’t care and have an `Oh well, whatever’ attitude. It can drive you crazy if you let it. You have to keep some perspective to stay sane.”67

The bright spot was that he finished the season well. In August and September, Berkman hit .311 with an OPS of 1.028 and 17 homers. “I felt pretty good the last two months of the season,” he said.68

Since 2002, Berkman had hit better in even-numbered years.69 In 2008 he stuck to the script — at least early in the season. He got off to a good start in April, then exploded. In May, he hit .471 with an OPS of 1.409, 9 homers and 22 RBIs. At one point in the streak, Berkman became just the second player in 50 years to get 19 hits in 25 consecutive at-bats.70 In the Astros’ first 81 games, he was batting .366 and on pace for a monster full-season of 54 doubles, 42 home runs, 140 runs scored, 212 hits, and 132 RBIs.

But such dreams, more often than not, wither in the heat of summer and Berkman’s were no different. From July 1 through August 9, he went 33 games and 111 at-bats without a home run. The nightmare continued in September, as Berkman suffered one streak of 0-for-17 and another of 0-for-22.

Still, the torrid start helped him earn him his fifth All-Star selection and finish fifth in voting for MVP. He hung on to lead the NL with 46 doubles, scored 114 runs, and drove in 106. Berkman said, “The name of the game for a guy like me is scoring runs and driving guys in. Those are two stats that are very important for me personally. That’s really my job. That’s what I’m supposed to do to help this team win.”71

Berkman was voted the Astros’ Most Valuable Player Award for 2008 by the Houston chapter of the Baseball Writers Association of America. It was his fifth team MVP award. Only Jeff Bagwell won more.

In February 2009 Alex Rodriguez admitted he had taken steroids, adding his name to the list of players implicated in the drug scandal. Berkman, who adamantly denied ever taking steroids, was frustrated that the cheats made all players look bad. He lamented, “The problem with this whole sordid mess (is) now everybody (is questioned). Even today, all of a sudden my name gets brought up in an article about steroids, and I’ve never even been anywhere close to that. But who’s going to believe me? The point’s well made, because we’re all guilty by association. One side of me is glad that these guys are getting outed.”72

Late in spring training that year, Berkman was diagnosed with tendinitis in his left biceps.73 The injury didn’t keep him from playing any early-season games, but on May 12 his batting average was only .187. He got turned around and, from that point on, he slashed .300/.421/.538/.960. But injuries allowed him to play only 136 games, causing unusually low totals in home runs, runs scored, and RBIs.

In 2010 Berkman entered the final season of his contract. After suffering a contusion in his left knee early in spring training, he needed surgery to remove associated cartilage debris.74 The injury caused him to miss the first 12 games of the season. Upon returning, he collected only 10 hits in his first 57 at-bats and on May 8 was batting only .175 with an OPS of .621.

With the Astros at 9-18 and having not made the playoffs since 2005, Berkman acknowledged that it was tough to play on a losing team, especially at his age. (He was 34.) He said, “This organization has been great to me. I love the Houston Astros. No matter what happens, I’m always going to be an Astro at heart. But as you get older, you definitely start to look at (being on a losing team), and you say, ‘How many sub-.500 seasons do you want to play?’”75

On July 31, the trading deadline, with Berkman having the worst year of his career and the Astros going nowhere, he was dealt to the New York Yankees for Mark Melancon and Jimmy Paredes. Berkman said, “I’m excited for a new challenge. Coming to a first-place team and a team that’s expected to go deep into the postseason is a great opportunity and one that I really felt like I couldn’t pass up.”76

Berkman started slowly with the Yankees, hitting only .200 and slugging .314 in August. In September, his batting average improved to .299, but his power did not return. After failing to hit any homers in August, he hit only one in September.

The Yankees lost the AL East title by one game but with a record of 95-67 easily qualified for the wild card. In the LDS, they swept Minnesota in three games, then lost in the LCS to the Rangers, four games to two. Berkman started five of the nine games, all but one against a right-hander, and batted .313 with a double, triple, homer, and four RBIs.

Berkman hoped to return to the Astros in 2011, but during a phone call, the team said it wasn’t interested. “It wasn’t a long conversation,” said a disappointed Berkman.77

His career with the Astros now over, Berkman ranked first in team history in on-base percentage (.410), slugging percentage (.549) and OPS (.959), second in home runs and OPS+, third in doubles, runs scored, and RBIs, fourth in batting average, and fifth in hits and WAR. The previous winter, Berkman had been inducted into the Astros Hall of Fame.78

On December 4, Berkman agreed to an $8 million, one-year contract with the St. Louis Cardinals.

In 2011 Berkman regained his old form. He rode hot opening and closing months to a batting average of .301 and an OPS of .959 (sixth in the majors) with 31 home runs and 94 RBIs. He earned All-Star honors, finished seventh in MVP voting, and won the NL Comeback Player of the Year Award.

In 2011 Berkman regained his old form. He rode hot opening and closing months to a batting average of .301 and an OPS of .959 (sixth in the majors) with 31 home runs and 94 RBIs. He earned All-Star honors, finished seventh in MVP voting, and won the NL Comeback Player of the Year Award.

Because Berkman played much better in 2011 than he had the previous year and was in better physical shape, fans and people in the Astros organization criticized him. Astros radio announcer Milo Hamilton said, “If he had (dedicated himself to training) the last couple years he was here, he could have finished out a really fine career in Houston.”79 But trainer Danny Arnold, who worked with Berkman for several years, disagreed. Arnold said, “It’s ludicrous to say he didn’t work. He was always conscientious.”80

On September 5 the Cardinals’ record was 74-67. It seemed they were out of playoff contention, 10½ games behind the division-leading Brewers in the NL Central and 8½ behind the Braves for the wild card. But from then until the end of the season, the Cardinals went 16-5 while the Braves went 7-15. During the 21-game streak, Berkman batted .413 and the Cardinals won the wild card by one game. They beat the Phillies in the LDS and the Brewers in the LCS and advanced to the World Series to face the Texas Rangers.

With St. Louis behind three games to two in the Series and losing 7-5 with two outs in the bottom of the ninth inning of Game Six, Berkman scored the tying run when David Freese hit a two-run triple. In the 10th, after the Rangers regained the lead at 9-7, Berkman drove in the tying run with a two-out single. The Cards won in the 11th when Freese led off with a home run. ESPN’s Buster Olney called it the greatest game in baseball history.81 Berkman went 3-for-5, scored four runs, and drove in three.

The next day, the Cardinals won Game Seven and Berkman, who went 1-for-3 and scored two runs, had his first and only World Series championship. In the seven games, Berkman collected 11 hits in 26 at-bats for a batting average of .423 and an OPS of 1.093.

Berkman played two more seasons — 2012 with the Cardinals and 2013 with the Rangers. In both, he was plagued by injuries and played just 32 games the first year and 73 the second. On January 29, 2014, Berkman announced his retirement82 and on April 5 he and good friend Roy Oswalt signed one-day contracts to retire as Astros. To honor the two, the team held a pregame ceremony during which fans showed their appreciation with several standing ovations. Berkman said, “We all kind of felt like we were all part of the Astros family.”83

In 2016 Berkman became head baseball coach at Second Baptist High School in Houston. That year, with former teammate Andy Pettitte as pitching coach, Berkman led the team to a state championship.84

But Berkman really wanted to be the head coach of his alma mater, Rice University. When Berkman’s coach at Rice, Wayne Graham, announced he was retiring after 2018, Berkman told him, “I’d love to follow in your footsteps.”85 However, he was passed over for the Rice job and thereafter resigned from Second Baptist in 2019, saying, “I was really coaching (at Second Baptist) to put myself in position to get the Rice job. When that didn’t work out, it took the wind out of my sails a little bit. I never intended to be a high-school coach for the rest of my life.”86

Looking back at his career, Berkman said, “Whether or not I’m a Hall of Fame-caliber player, I feel like in my decade-plus, from a percentage standpoint I stack up against anybody. I may not retire with what some people think are enough home runs and RBIs to merit induction, but in my mind I can hit with anybody in that building.”87

Berkman was right, if percentage statistics were all that mattered. He would be arguably among the 30 best offensive players of all time. His on-base percentage (.406) and slugging percentage (.537) would place in him the top 25 of Hall of Famers and his OPS (.943) would be number 18 for players in the Hall (as of January 2020).

However, Berkman was also right on his second point. He did not accumulate enough hits, home runs, or RBIs necessary to impress traditional Hall of Fame voters. He finished his career with 1,905 hits and 1,234 RBIs. Outstanding totals, but 1,905 hits are not among the top 300 of all time and 1,234 RBIs not among the top 100. He hit 366 home runs, impressive in 1960, but not in 2020. Also, he had no home-run or batting titles on which to hang his hat. The only high-profile category in which he led the league was RBIs, and then only once. In 2019 Berkman’s first year of eligibility for the Hall of Fame, he got only 1.2 percent of the vote. Since that is less than the 5 percent minimum to remain on the ballot, Berkman will not appear on future ballots.

But if making the Hall were solely based on character, Berkman would be a lock. After he was traded from the Astros, columnist Richard Justice wrote, “He is … smart, funny and thoroughly decent, a voracious reader and a devoted husband to his wife and a doting father to his four daughters. We’ve been blessed.”88

Even though he had been fired by Berkman, sports agent Brian Peters gushed, “He’s the sweetest kid in baseball. He is absolutely the most genuine young man I’ve ever been around and the kindest, most pure human being I’ve ever met. My association with Lance has made me a better person.”89

In 2010 Lance and Cara donated over $2 million to The Lord’s Fund, a foundation they established. It placed them seventh on Forbes magazine’s 2012 list of most generous celebrities.90

Last revised: September 9, 2020

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Paul Doutrich and Len Levin and fact-checked by Chris Rainey.

Sources

Unless otherwise noted, statistics come from baseball-reference.com.

Notes

1 On-base Plus Slugging is a statistic which, as its name suggests, is the sum of a player’s on-base percentage and slugging percentage. It correlates very well with more complex methods that evaluate the runs for which a batter is responsible.

2 http://m.mlb.com/glossary/advanced-stats/on-base-plus-slugging-plus.

3 http://m.mlb.com/glossary/miscellaneous/slash-line. Accessed December 11, 2019. A batter’s slash line consists of batting average, on-base percentage, slugging percentage and on-base percentage plus slugging percentage. These four simple rate statistics combine to rather accurately describe a player’s offensive ability.

4 Unless otherwise stated, all rankings are from the Play Index of baseball-reference.com. Search criteria are retired players who had 5,000 or more plate appearances after 1901. I chose 1901 because that was the first year of the AL, it is the start of a century, and baseball was just too different in the 1800s.

5 Thomas Godley, “Berkman Swings into SWC Spotlight,” New Braunfels (Texas) Herald-Zeitung, April 16, 1995: 10A.

6 https://playerwives.com/mlb/texas-rangers/lance-berkmans-wife-cara-berkman/. Accessed December 18, 2001.

7 Sean Burgess, “Berkman a Big Hit on the Canyon Diamond,” New Braunfels Herald-Zeitung, May 18, 1994: 10A.

8 https://si.com/vault/2001/08/06/308493/the-story-of-his-life-lance-berkman-loves-a-good-yarn-but-the-best-one-yet-is-about-his-stunning-rise-as-an-offensive-force-for-the-astros. Accessed December 18, 2019.

9 Olin Buchanan, “Breakthrough Season Could Make Berkman,” Austin American-Statesman, June 19, 2001: C1.

10 “Canyon High School Lists Academic ‘All-Stars’ on 1st Six Weeks Honor Roll,” New Braunfels Herald-Zeitung, November 7, 1993: 5B.

11 Burgess.

12 Kirk Bohls, “Berkman’s More Than Mr. Nice Guy,” Austin American-Statesman, April 28, 2002: C1.

13 Richard Justice, “A Job Well Done,” Houston Chronicle, September 27, 2002: Sports 1.

14 Thomas Godley, “Former Canyon Baseball Standout Sets SWC Mark,” New Braunfels Herald-Zeitung, March 14, 1996: 5.

15 “Berkman Adds to Stellar 1995 Season,” New Braunfels Herald-Zeitung, August 20, 1995: 6A.

16 Godley, “Former Canyon Baseball Standout Sets SWC Mark.”

17 David Dekunder, “Berkman Makes His Mark,” New Braunfels Herald-Zeitung, March 23, 1997: 1B.

18 “Southwest Conference Baseball Statistics,” Austin American-Statesman, May 9, 1996: D6.

19 “Berkman Keys Rice in SWC Tourney,” New Braunfels Herald-Zeitung, May 17, 1996: 5.

20 David Dekunder, “Berkman Makes His Mark.”

21 en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1997_NCAA_Division_I_Baseball_Tournament#All-Tournament_Team.

22 Rick Cantu, “Rice Slides Into 1st World Series,” Austin American-Statesman, May 26, 1997: C1.

23 Cantu.

24 Associated Press, “Rice Draftees Head Rich Crop of Texans,” Victoria (Texas) Advocate, June 5, 1997: 2B.

25 “Berkman a Finalist for Smith Award,” New Braunfels Herald-Zeitung, June 25, 1997: 1B.

26 “Berkman, Astros Agree on Minor-League Deal,” New Braunfels Herald-Zeitung, June 22, 1997: 1B.

27 David Barron, “Anniversary Day,” Houston Chronicle, July 16, 2009: Sports 1.

28 https://redbirdrants.com/2017/07/31/st-louis-cardinals-christian-day-2/.

29 https://stltoday.com/news/local/lance-berkmans-comments-upset-transgender-supporters/article_64e3cfb3-4f0d-5723-be76-0b6aa5cb0463.html.

30 Jose De Jesus Ortiz, “Stepping Up to the Plate,” Houston Chronicle, January 26, 2007: Sports 1.

31 Tom Erickson, “Batting a Thousand,” New Braunfels Herald-Zeitung, July 14, 1998: 1.

32 Tom Erickson, “Berkman Waits for Deal,” New Braunfels Herald-Zeitung, June 8, 1997: 1B.

33 “The Berkman Line,” New Braunfels Herald-Zeitung, August 15, 1997: 1.

34 Rex Hoggard, “Cobras’ Berkman Makes the Effort,” Orlando Sentinel, August 17, 1997: C-12.

35 Hoggard.

36 “The Berkman Line,” New Braunfels Herald-Zeitung, September 6, 1998: 3B.

37 Tom Erickson, “The View from Left Field,” New Braunfels Herald-Zeitung, July 17, 1998: 1B.

38 Mike Christensen, “Booster Club Gives MVP to Sanchez,” Jackson (Mississippi) Clarion-Ledger, August 24, 1998: 3C.

39 Tom Erickson, “Berkman’s Fan Club meets for First Time,” New Braunfels Herald-Zeitung, November 25, 1998: 9A.

40 Peter Brown, “Berkman Recovering Well from Surgery on Left Knee,” New Braunfels Herald-Zeitung, April 20, 1999: 10.

41 “Lance Is Back,” New Braunfels Herald-Zeitung, May 27, 1999: 10.

42 Neil Hohlfeld, “Berkman’s Back in Town as Big-Leaguer,” Houston Chronicle, July 17, 1999: Sports 1.

43 Peter Brown, “Rising Star,” New Braunfels Herald-Zeitung, July 20, 1999: 8.

44 Joseph Duarte, “Astros Activate Everett,” Houston Chronicle, August 6, 1999: Sports 2.

45 Carlton Thompson, “Astros Summary,” Houston Chronicle, April 17, 2000: Sports 4.

46 Neil Hohlfeld, “Berkman’s Having a Blast,” Houston Chronicle, July 10, 2000: Sports 9.

47 To be considered a rookie, a player cannot have spent 45 or more days on a major-league roster prior to September 1. In 2009 Berkman spent only 41 days available to the Astros because he had been sent to New Orleans for six days from August 7 to 12. But because his stay in the minors was less than 20 days, he continued to accumulate major-league service time, making his total time on the major-league roster 47 days, thus taking away his rookie status.

48 Joseph Duarte, “Bests and Worsts of Camp,” Houston Chronicle, March 29, 2001: Sports 7.

49 John P. Lopez, “Berkman Proving Just Right in Left,” Houston Chronicle, March 3, 2001: Sports 1.

50 Six of the top 10 NL seasons for doubles came in the 1930s. Three others, including Berkman’s, occurred from 1999 through 2001.

51 Jose De Jesus Ortiz, “Coming of Age,” Houston Chronicle, October 9, 2001: Special 4.

52 https://si.com/vault/2001/08/06/308493/the-story-of-his-life-lance-berkman-loves-a-good-yarn-but-the-best-one-yet-is-about-his-stunning-rise-as-an-offensive-force-for-the-astros. Accessed December 18, 2019.

53 Carlton Thompson, “Year in Review 2001,” Houston Chronicle, December 30, 2001: Sports 1.

54 Joseph Duarte, “A Meeting of the Minds,” Houston Chronicle, January 30, 2002: Sports 1.

55 Neil Hohlfield, “Berkman Strives for Production,” Houston Chronicle, August 9, 2003: Sports 3.

56 Dale Robertson, “Berkman Dismisses One-Sided Thinking,” Houston Chronicle, February 26, 2003: Sports 1.

57 “Home Run Derby,” Houston Chronicle, July 13, 2004: Special 7.

58 Jose De Jesus Ortiz, “Surgery Repairs Berkman’s Knee,” Houston Chronicle, November 13, 2004: Sports 13.

59 Jose De Jesus Ortiz, “Astros, Berkman Sacked,” Houston Chronicle, November 6, 2004: Sports 1.

60 Jose De Jesus Ortiz, “Berkman a Long-term Astro,” Houston Chronicle, March 20, 2005: Sports 1.

61 Neil Hohlfeld, “Want to Win? More Power to You,” Houston Chronicle, May 15, 2005: Sports 8.

62 Neil Hohlfeld, “Slugger Revels in Joys of Summer,” Houston Chronicle, July 30, 2005: Sports 14.

63 Brian McTaggart, “Berkman Won’t Miss Much Time,” Houston Chronicle, January 27, 2006: Sports 10.

64 John P. Lopez, “Berkman Definitely Is the Answer,” Houston Chronicle, April 19, 2006: Sports 1.

65 Lopez, “Berkman Definitely Is the Answer.”

66 Jose De Jesus Ortiz, “TV Fanatic Berkman Switches Off Royals,” Houston Chronicle, June 18, 2006: Sports 1.

67 Brian McTaggart, “What’s Eating Big Puma,” Houston Chronicle, June 10, 2007: Sports 1.

68 Joseph Duarte, “Berkman’s Back in Zone,” Houston Chronicle, March 16, 2008: Sports 1.

69 From 2002 through 2009, Berkman’s average OPS+ in even years was 158, while in odd years it was 138.

70 Jose De Jesus Ortiz, “The Big Puma Is on the Prowl,” Houston Chronicle, May 13, 2008: Sports 1.

71 Jose De Jesus Ortiz, “A Happy Landing,” Houston Chronicle, September 10, 2008: Sports 1.

72 Jose De Jesus Ortiz, “Berkman: Presumption of Innocence Gone for All,” Houston Chronicle, February 10, 2009: Sports 1.

73 Brian McTaggart, “Berkman Sidelined by Injury,” Houston Chronicle, March 30, 2009: Sports 1.

74 Zachary Levine, “Slugger’s Surgery Smooth Sailing,” Houston Chronicle, March 14, 2010: Sports 9.

75 Jerome Soloman, “Berkman Open to a Trade if Team Isn’t a Contender,” Houston Chronicle, May 6, 2010: Sports 1.

76 Zachary Levine, “The Berkman Trade in a New York State of Mind,” Houston Chronicle, August 1, 2010: 1.

77 Richard Justice, “Jilted by Astros, Berkman Eagerly Anticipates Offers,” Houston Chronicle, November 28, 2010: Sports 1.

78 Chandler Rome, “Killer B’s Reunited in Team’s Hall of Fame,” Houston Chronicle, January 19, 2010: C7.

79 Zachary Levine, “Fans Envelop Berkman in Group Hug,” Houston Chronicle, April 27, 2011: 7.

80 Richard Justice, “No Apologies, but a Renewed Career and Sense of Responsibility,” Houston Chronicle, April 27, 2011: 1.

81 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2011_World_Series. Accessed December 28, 2019.

82 Associated Press, “Former Astro, Ranger Berkman Retires from Baseball,” Longview (Texas) News-Journal, January 30, 2014: 2B.

83 Associated Press, “Berkman, Oswalt Sign One-Day Deal with Astros,” Brownsville (Texas) Herald, April 6, 2014: B6.

84 Brian T. Smith, “Like Old Times,” Houston Chronicle, May 26, 2016: C1

85 Joseph Duarte, “Rice Baseball,” Houston Chronicle, May 12, 2018: C005

86 https://larrybrownsports.com/baseball/lance-berkman-steps-down-second-baptist-coach/498957. Accessed December 9, 2019.

87 Joe Strauss, “Nearing the End?” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 25, 2012: B1.

88 Richard Justice, “The Berkman Trade,” Houston Chronicle, July 31, 2010: Sports 1.

89 Bohls.

90 forbes.com/sites/andersonantunes/2012/01/11/the-30-most-generous-celebrities/#1478845e4994. Accessed April 12, 2020.

Full Name

William Lance Berkman

Born

February 10, 1976 at Waco, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.