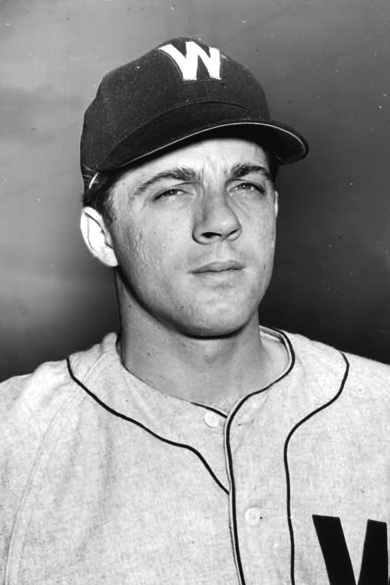

George Genovese

The manager of the Hotel del Comercio in Caracas, Venezuela, summoned George Genovese for a phone call from the San Francisco Giants in November 1963. It sent Genovese’s hopes soaring. “Maybe I’m their new manager,” he said to his wife, June. When the call was completed, Genovese was crestfallen. His career as a manager was over.

The manager of the Hotel del Comercio in Caracas, Venezuela, summoned George Genovese for a phone call from the San Francisco Giants in November 1963. It sent Genovese’s hopes soaring. “Maybe I’m their new manager,” he said to his wife, June. When the call was completed, Genovese was crestfallen. His career as a manager was over.

Instead, he was on a new and unexpected career path. It was one that would thrust him into baseball immortality as “our industry’s titan,” according to longtime scout Mark Snipp.1 Though Genovese played in just three big-league games himself (in 1950), he signed close to 250 players in all, 44 of whom reached the majors. “One of the greatest scouts of that time, of any time,” said Terry Reynolds, former scouting director for the Los Angeles Dodgers, in 2010.2 “The Master,” proclaimed celebrated baseball executive, Roland Hemond.3

George Genovese was christened for George Washington, whose birthday (February 22) he shared. Genovese was born in 1922 on Staten Island, New York City. He was the fifth of eight children of Italian immigrants, Ernst and Anna Genovese. Both of them grew up in Campania, the region of southern Italy that includes Naples and Pompeii. They grew up about 40 miles apart but never knew each other until they met one day on a street car in New York City.

Ernst Genovese was a riveter who worked in Staten Island’s shipyards and on burgeoning high-rise buildings in Manhattan. The Great Depression brought hard times to the Genovese household. During his adolescent and teenaged years, George worked after school to help the family. He shoveled snow in the winter, worked in a pool hall, assisted a produce delivery man, and helped a blacksmith. George had four older brothers: Frank, Tony, Dominic, and Jim. Like them, George Genovese developed a passion for baseball.

Enthusiasm for the game wasn’t limited to the Genovese boys — sisters Josephine and Louise played as well. When Josephine entered high school, however, she told George that it was time for her to be a lady, and she largely quit playing ball. Still, she was later recruited by the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League. She had a well-paying secretarial job that she did not wish to relinquish, so she turned the offer down. Nonetheless, when AAGPBL teams barnstormed in the New York area, they invited her to play, and she got into a few games (it s not known when or with whom). A third sister, Rose, succumbed to injuries suffered in an automobile accident at the age of two.4

The economics of the time made Ernst Genovese concerned about his son’s love of baseball. “Our father used to say, ‘If you have a trade, you have something. If you play baseball, you are only playing,’” Genovese said. Despite their father’s concern, each of the Genovese sons would be offered an opportunity to play the game for pay. In the summer of 1940, George would follow his brothers into the professional game but not without frustration.

As a sophomore at Port Richmond High School, Genovese was approached after a game by the prolific Washington Senators scout, Joe Cambria. The man had been impressed by both the shortstop, Genovese, and a pitcher in the game, Karl Drews. The scout proposed that the boys sign postdated contracts that would go into effect once they had graduated from high school. Both Genovese and Drews were convinced that their parents would never agree to such a scheme and turned the idea down.

For the next two years, Genovese neither saw nor heard from another scout. When he graduated from high school in 1940 and received no offers to sign, the teen became disillusioned with baseball. His brother Frank, who was known as “Chick”, was in the midst of a 13-year minor-league career. Another brother, Tony, had spent a season with a St. Louis Cardinals Class D farm club. Jim had signed with Cleveland and was in spring training with their Class D farm club before he became homesick and quit. Dominic had played with the traveling House of David team and drew interest from scouts but gave up the game when a well-paying job opportunity was presented.

George became convinced that his 5’6” stature was to blame for the scarcity of scout interest. Urged by the president of the local Catholic Youth Organization, Genovese traveled with a high school teammate to Waterbury, Connecticut, to participate in a St. Louis Cardinals tryout camp. Genovese and his teammate slept in the barn of a sympathetic farmer. Almost 800 hopefuls took part in the week-long event. The scout in charge of the camp, Roy Dissinger, quickly identified Genovese as having the best throwing arm and being among the faster runners of the throng of prospects. At the conclusion of the multi-day tryout, Genovese was one of just 12 players whom Dissinger signed. “He told me I had a major-league future,” said Genovese. “He said ‘You’re a good little infielder. You can run and you’ve got a good arm. I think you can be a ballplayer.’”

Genovese spent five seasons working his way through the Cardinals’ farm system. His climb was interrupted for three years by World War II. The United States Army shipped the New Yorker to the Pacific theatre, where he was stationed on the island of Ie Shima. Troops there prepared for the assault on Okinawa. One evening the Japanese launched a bombing raid on the base. Air raid sirens sent Genovese and dozens of soldiers scrambling for cover. In his haste, Genovese fell 15 feet from where he had been working to the deck of the ship. He landed on his right shoulder, and the right side of his face slammed against the deck. The injuries damaged his shoulder. His strong throwing arm was never the same.

When Genovese was released from the base hospital, he became embroiled in a dispute with his superiors. He was entitled to the Purple Heart, the military medal awarded to those wounded at the hands of the enemy during time of war. Genovese refused to accept the medal. “I told them, ‘That’s for those boys on the front line. All I did was have a bad fall,’” he recalled in a 2010 conversation.

At the end of the war, Genovese sailed home. He received his discharge and weeks later resumed his baseball career. He spent the 1946 season playing Class B ball at Lynchburg. He was promoted in 1947 and played for Omaha, a Class A club in the Cardinals organization.

Amid a series of job challenges in the search for “the next Marty Marion,” Genovese grew frustrated in the Cards chain. He asked for a change of scenery, and in the spring of 1948, his contract was sold to the Denver Bears. Advice from his manager in 1948, Mike Gazella, resulted in the shortstop’s best season in pro ball. Gazella urged Genovese to utilize his speed and bunt wherever possible. “Even if you bat .150, if you bunt .150 you’ll have a .300 average,” the manager explained. During the final weeks of that season, Genovese was hitting .312 when his contract was purchased by the Hollywood Stars under a working agreement with Denver.

Playing at the pinnacle of minor-league baseball, Genovese was part of a cast that led Hollywood to the 1949 Pacific Coast League pennant. His play drew attention from big-league clubs. In the November minor-league draft, Genovese was selected by the Washington Senators. Off the field his personal life was on the upswing, too. Genovese had fallen head over heels for a model and aspiring actress, June Montgomery. The couple made plans to marry in the summer of 1950 and make Southern California their home.

Throughout the exhibition schedule, during spring training in 1950, Genovese launched a spirited battle with Sam Dente for the Senators’ shortstop job. “Genovese has been staging a fielding show every time they’ve had him in the lineup,” Shirley Povich wrote in The Sporting News.5 Bucky Harris, the Senators’ manager, had other ideas, however. He saw Genovese as his utility man. One month into the season, Genovese had appeared in just three games. Twice he had pinch-hit, and once he was sent in to pinch-run. Miserable at sitting on the bench while Dente struggled, missing his bride-to-be, and frustrated to be making less money than he did the year before with Hollywood, Genovese approached Harris between games of a May 14 doubleheader in Boston. He asked to be sent back to Hollywood. Harris pleaded with Genovese to reconsider. The player refused. A day later Genovese was on the receiving end of a tongue-lashing from the owner of the Senators, Clark Griffith, who ordered the player to Washington’s Class AA club in Chattanooga. It was in Chattanooga where Genovese and June Montgomery wed in July. They remained together until she died in 2000.

During the offseason, Genovese noticed an article in a Los Angeles newspaper that Hollywood was seeking a shortstop. He phoned Fred Haney, the manager, to express interest, and the club purchased his contract from Washington. Genovese helped the Stars contend for the 1951 Pacific Coast League title. Following the season his contract was purchased by the Pittsburgh Pirates. During the first few days of spring training, however, general manager Branch Rickey summoned Genovese for a chat. “George, you’ve slowed down a step. You’re not going to go back to the big leagues,” Rickey said bluntly. “I think you’ve got a good career ahead of you, though. I’d like to make you a manager.” Thus began a seven-year run in the Pirates chain that would take Genovese from Batavia, New York, to St. Jean, Quebec; Hutchinson, Kansas; Salinas, California; then Mexico City. In this role sprouted ambitions to manage in the big leagues.

During his first spring training with the Pirates organization, Genovese exhibited an eye for talent that gained Rickey’s attention. He lobbied Rickey to sign a 17-year-old tryout candidate, and thus R.C. Stevens, a future major leaguer, was added to his club. By the end of his first season in the organization, Genovese had become a trusted Rickey confidant. He was asked by the Pirates’ general manager to run tryout camps with Pie Traynor in Pittsburgh and Howie Haak and Clyde Sukeforth in Mexico. Genovese was given a stack of contracts and told to sign players who sparked his interest while home in Southern California during the offseason.

During the winter of 1954-55, Rickey wanted more evaluations on a young outfielder whom he sought. Thus, he arranged for Genovese to manage the San Juan Senators in the Puerto Rican Winter League. Genovese filed regular reports about the coveted talent, who played center fielder for San Juan’s rivals, the Santurce Crabbers. It was Roberto Clemente.

While Genovese was managing in Puerto Rico, his family expanded when June gave birth to the couple’s only child, their daughter, Kathleen.

In 1955 Genovese became part of another Branch Rickey project. For several years Rickey had sought to include the Mexican League in the U.S minor-league system. Once the idea came to fruition in 1955, Pittsburgh made the Mexico City Tigers, one of their Class Double-A affiliates. Genovese was hired to manage the club and was the first American to manage in the Mexican League (aside from Rogers Hornsby’s brief stint with Veracruz in 1944). He successfully guided the Tigers to the league title.

Genovese remained with the Tigers through the 1958 season. Going into 1959, the working agreement between Mexico City and Pittsburgh ended, and so Santos Amaro replaced Genovese as manager.6 Genovese then became a coach with the Salt Lake City Bees of the PCL.

Rickey stepped down as Pirates GM in October 1955 but remained a special advisor until becoming president of the Continental League in August 1959. The Pirates soon restructured their farm system. Upon completion of the 1959 season, Genovese was among the managers and coaches who were let go as a result. On learning the news, George’s brother Chick sprang into action. The older Genovese was now a scout for the San Francisco Giants. He urged his employer to give his brother a job. Jack Schwarz, the Giants’ director of scouting and the farm system, hired the younger Genovese to manage a Class D club at Artesia, New Mexico.

In his first spring training with the Giants, Genovese showed a discerning eye for talent. While other managers urged the release of two rookies, Jesús Alou and Minervino Rojas, Genovese argued against it and prevailed. Both players would later become capable big-leaguers. A year later he saved José Cardenal and Bob Chance from being let go, and each went on to achieve success in the major leagues. When the Giants allowed newly-hired Los Angeles Angels’ manager Bill Rigney to peruse their scouting files to prepare for the expansion draft, one report in particular caught his attention. It was a report that George Genovese had written about an opposing shortstop whom he liked. Emboldened by the report, Rigney and the Angels selected the player, Jim Fregosi.7

Genovese managed Class D clubs in Artesia (New Mexico) and El Paso in 1960 and 1961. He was promoted to manage the Giants’ Class AA club in 1962, which was also in El Paso. Genovese guided the Sun Kings to the Texas League pennant. That squad was a prolific offensive force. An almost nightly occurrence after games was a parade of scouts and executives into the manager’s office. Genovese unabashedly praised his players and urged the scouts and executives to consider them for their organizations. “These boys had no future with the Giants,” Genovese explained. “We had Willie] Mays and Willie] McCovey. I was for these boys getting a chance.” The endorsements led to trades and draft selections that brought big-league opportunities to Cardenal, Rojas, Paul Doyle, Vic Roznovsky, Charlie Dees, and Moose Stubing. The manager’s early morning workouts and zealous mentoring changed the career track for Manny Mota, Randy Hundley, and Carl Boles, each of whom had struggled before playing for Genovese.

Swayed by these observations and successes, Jack Schwarz proposed an idea to Horace Stoneham, owner of the San Francisco Giants. Armed with Stoneham’s blessing, on November 19, 1963, Schwarz phoned Genovese, who was managing the Caracas Leones in the Venezuelan Winter League, and told him his contract to manage El Paso had been terminated. He was now the Giants’ Southern California scouting supervisor. Genovese was incensed. He told Schwarz he would quit to manage somewhere else. “George, managers are hired to be fired,” Schwarz said. “If you do the job I think you can do, you’ll be scouting for as long as you can see to drive a car.”

In a letter typed the following morning, Schwarz wrote, “While you do not welcome the change, I can see a big silver lining in it. The richest scouting area in the world for ballplayers right now is Southern California. We have not been getting our share of them.”8

Genovese stewed before he agreed to take the job, but only for one year. “And if I don’t like it, I’m going to look for a managing job,” he told Schwarz.

By the time Genovese returned home from Venezuela, he had developed a plan. He carried several ideas into the new role, such as Branch Rickey’s regard for power and speed. “Mr. Rickey used to say, ‘You can’t take power from anybody, and you can’t take speed. If you’ve got a guy with power, you’ve got to stay with him until he shows you he can’t play,’” Genovese said. His own managing experience evoked an appreciation for versatility. The experience Genovese went through as a teenager to get signed made him place a premium on players who displayed passion for the game. Foremost in Genovese’s plan was the idea to start a semipro team.

Knowing that Southern California was a hotbed of semipro ball, the new scout advertised in local newspapers for ballplayers to form his own team. “It’ll be like holding a tryout camp every weekend,” he told a neighbor. Dozens of top area high school players flocked. An associate scout, Evo Pusich, brought a raw, fleet outfielder from Riverside.

Genovese was almost instantly impressed with the potential of the player, Bobby Bonds. Soon, Bonds was making the 150-mile round trip every weekend to play for the scout’s team. Dave Garcia, a Giants minor-league manager, pointed Genovese to a San Diego prospect, Ken Henderson. Bonds and Henderson became the first two prospects that Genovese funneled into the Giants’ farm system. One year later Bonds was being hailed as the “Next Willie Mays,”9 and Henderson was in the big leagues and praised as, “the finest young player I’ve ever seen,” by former Houston manager, Harry Craft.10

His first season in the profession lit a competitive fire in Genovese. He abandoned managing pursuits, except for two occasions. Prior to the San Diego Padres’ inaugural 1969 season, Genovese was offered a place on Preston Gómez’s coaching staff. After pondering the offer, Genovese turned his friend down. Instead, he seconded the idea to offer the job to Sparky Anderson. Following the 1976 season, the Giants considered Genovese to replace Bill Rigney as their manager. After meetings and much discussion, they hired Joe Altobelli instead.

While rival scouts focused on more polished prospects, Genovese came to view his semipro team as an incubator. The team offered the sort of game experience that could buff raw talent into gleaming gems. Games were free from the pressure of winning or building impressive statistics. The summer of 1967 saw the scout’s idea pay dividends. That spring, one of the scout’s bird-dogs, a former minor-league opponent, Jack French, brought two raw players for evaluation: George Foster and Garry Maddox. Genovese was smitten. He quickly made it a point to regularly pick up Foster after school and work him out. “Most scouts don’t work with individuals. He did,” Foster said. “Every day after school he would pick me up. I’d hit and he’d throw batting practice.”11 Genovese instructed French to do the same with Maddox. Both became regulars on the scout’s weekend team. “Getting the at-bats was critical,” Maddox recalled. “It was an important way to raise your game.”12

After he had spent the summer working with the two, Genovese put Maddox and Foster on his draft list, and the pair was chosen by the Giants in January 1968. The scout directed the outfielders to junior colleges for additional seasoning but Maddox was soon cut. Genovese was not deterred and in the spring of 1968 he signed both Maddox and Foster. Foster played poorly. “I went to see Foster at El Camino College to see if I should put him on my draft list,” longtime scout Bob Harrison recalled. “He didn’t hit a lick. Then I go scout the California League [in 1969], and Foster’s leading the league in hitting. How’d that happen?”13 After the work Genovese did with him to improve his skills, Foster would spend 18 seasons in the big leagues. He earned the Most Valuable Player Award in 1977, finished second in the voting for the honor in 1976, and third in 1981. Maddox spent 15 years in the big leagues and earned the Gold Glove Award for fielding excellence eight times.

In the spring of 1968, Genovese was startled by the dazzling play of an unheralded outfielder during an American Legion game. He soon realized that he and every other scout had seen the player — but as a pitcher who had performed poorly for his high school team. Scouts often left without seeing the young man bat. Two weeks later the scout’s prodding pushed the Giants to select the player, Gary Matthews, in the first round of the draft. In 1973 Matthews was voted National League Rookie of the Year.

Through the 1970s Genovese progressed from profitable evaluator to prolific scout. “Nobody in the history of the game was better at recognizing raw talent,” said longtime scout and Southern California area coach, Artie Harris.14 His work paired polishing the raw, such as Jack Clark, Randy Moffitt, and Chili Davis, with recommending collegiate standouts like Dave Kingman and Jim Barr. Scouts soon scouted the scout. It was not uncommon for rival scouts to turn up and watch Genovese’s semipro team play or follow him to see who he was scouting. Their bosses coveted Genovese as well. The Blue Jays, Dodgers, Mets, Reds, Expos, and Mariners dangled lucrative offers to pry him from the Giants, to no avail.

On September 13, 1973, proof of how prolific Genovese had become was on display in a game between the San Francisco Giants and San Diego Padres. In the seventh inning of the game, a total of seven players in the Giants’ lineup were players whom he had signed. Later that month in games against the Dodgers, the Giants fielded lineups with five and six Genovese signees. These were not just average ballplayers; they were standouts. In the 1979 All-Star Game, four players that Genovese signed — Clark, Foster, Kingman, and Matthews — were selected to play.

From 1965 to 1996, the Giants had at least one player on their ballclub who had been signed by Genovese. In each of the 1971, 1972, and 1975 seasons, 10 players whom Genovese signed played for the San Francisco Giants. From 1968 through 2007, a span of 39 years, a player signed by George Genovese was a starter in the big leagues. “If they put every ballplayer he signed on two clubs, they’d battle for the World Series,” exclaimed former manager Dave Garcia.15

Over time, Genovese no longer had to advertise for players for his team. Publicity about his success made hopefuls and their parents seek him out. He recommended that 14-year-old Mike Lieberthal abandon playing shortstop and become a catcher. Lieberthal would catch for 14 years in the big leagues and was twice an All-Star. After watching 14-year-old Dmitri Young take batting practice, Genovese gushed to the player’s father that he wished he could “sign him right now!” He recommended that Young learn to play as many positions as he could. “He’s the reason I was able to play so long [13 seasons] in the big leagues,” Young later said.16

On August 12, 1994, in a move that was described as cost-cutting, George Genovese was fired after 34 years with the San Francisco Giants’ organization. As soon as he heard the news, Los Angeles Dodgers general manager Fred Claire showed up in the office of his scouting director, Terry Reynolds. “We need to hire this guy,” Claire said. “He’s a great scout. He can help us.”17 In an instant, Reynolds had Genovese on the phone and the scout accepted his job offer. Genovese served as a special assistant to Claire. He made recommendations, such as a switch from catching to first base for Paul Konerko, and he gave advice on prospective trades. Following sales of the franchise, Genovese served as a scouting consultant.

At the inaugural Professional Baseball Scouts Foundation dinner on January 10, 2004, the organization’s first lifetime achievement award was presented to George Genovese. During the presentation, it was announced that from that night forward the award would be known as the George Genovese Award.

On November 15, 2015, George Genovese succumbed to sepsis at St. Joseph’s Medical Center in Burbank, California. He was 93 years old. Genovese left a legacy that will be admired forever and never be duplicated. “For me,” said former Los Angeles Dodgers general manager, Dan Evans, “he’s the greatest scout of all time.”18

- Related link: Check out more biographies of baseball scouts in SABR’s Can He Play? A Look At Baseball Scouts And Their Profession

Acknowledgements

Much of the information for this story comes from interviews with George Genovese conducted for the book, “A Scout’s Report, My 70 Years in Baseball.” McFarland & Co, 2015 as well as many personal conversations between the author and Mr. Genovese from January 10, 2010, to November 3, 2015. Third party quotes, unless otherwise noted, are as recalled by Genovese. The author also extends his deep gratitude to the daughter of Mr. Genovese, Kathleen Haworth, and to his niece, LeeAnne Marino.

This biography was reviewed by Norman Macht and Rory Costello. It was fact-checked by Kevin Larkin and Warren Corbett.

Sources

Statistical information for this story is from The Sporting News and Baseball-Reference.com. Lineup information is from Retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 Personal conversation with Mark Snipp on March 12, 2015.

2 Conversation with Terry Reynolds, August 5, 2010.

3 Conversation with Roland Hemond, January 15, 2010.

4 The bulk of the information for this essay comes from interviews with George Genovese from January 10, 2010, to November 3, 2015.

5 Shirley Povich, “Harris High on His Four Coast Buys,” The Sporting News, April 12, 1950.

6 Roberto Hernandez, “Avila Weighing Business Bid–May Quit Game,” The Sporting News, March 4, 1959, 28.

7 Conversation with Jim Fregosi, August 24, 2012.

8 Letter from Jack Schwarz to George Genovese, November 20, 1963.

9 Gene Warren, “Rookie at Lexington Flashing Promise as Next Willie Mays.” The Sporting News, July 3, 1965.

10 Bob Stevens, “Another Mays in the Making? Take a Look at Ken Henderson.” The Sporting News, September 11, 1965.

11 Conversation with George Foster, October 10, 2010.

12 Interview with Garry Maddox, December 16, 2010.

13 Interview with Bob Harrison, January 9, 2010.

14 Conversation with Artie Harris, January 10, 2010.

15 Dave Garcia, telephone interview with author, February 3, 2010.

16 Conversation with Dmitri Young, December 3, 2011.

17 Conversation with Fred Claire, August 4, 2010.

18 Bill Shaikin, “George Genovese, ‘greatest scout of all time,’ dies at 93.” Los Angeles Times, November 16, 2015.

Full Name

George Michael Genovese

Born

February 22, 1922 at Staten Island, NY (USA)

Died

November 15, 2015 at Burbank, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.