Philadelphia Athletics batterymates, 1901-1914

This article was written by Phil Williams

Winning six pennants from 1901 to 1914, the Philadelphia Athletics were the first sustained American League dynasty. At the heart of Connie Mack’s teams in this era were set pitcher-catcher batteries. This study examines their statistical accounting and insights into their makeup, and considers their place within the evolution of the sport.

“It is especially a matter of the first importance to a strategic pitcher that he should have a first-rate man behind the bat to second him in all his little points of play,” stated the 1894 Spalding’s Base Ball Guide. “For this reason … pitchers and catchers should always work together in pairs.” Signals, strategies towards baserunners, and means to catch “a batsman ‘out of form,’” were likely to be uniquely employed within the pitching box and behind the plate. Thus, “a first-rate catcher for one pitcher might be almost useless for another.”1

Mack’s own background reflects the 19th-century emphasis on set batteries. Pitchers commonly insisted upon their own catcher, as Washington’s Jim Whitney would in 1887, demanding that Mack catch him. A senior catcher might also be assigned to calm and mentor a young pitcher. As Pittsburgh’s player-manager in 1895, Mack assigned himself to work with the embattled Frank Killen.2 Multiple batteries required positional depth, illustrated by basic metrics. As a rookie with Washington in 1887, Mack had led the National League by appearing in 76 games as a catcher (60% of his team’s 126 games).

Yet, even as the 1894 Spalding Guide went to print, the wisdom of set batteries was being questioned. Rule changes pushed pitchers back to the present-day 60 feet, 6 inches from the plate. The greater impact upon pitchers’ arms required a team’s staff to be expanded. Meanwhile, innovations in a catcher’s equipment made his professional life more durable. Catchers, baseball historian Peter Morris suggests, became increasingly “anonymous and interchangeable,” and the emphasis on set batteries receded.3

Seen through this perspective, it was not unusual that in the Athletics’ inaugural 1901 season, Doc Powers was the starting catcher for 108 of Philadelphia’s 137 games. Yet it was the heaviest workload any Athletics backstop would shoulder in the Deadball Era. Mack’s initial twentieth-century teams would be largely defined by a nineteenth-century concept.

The onset of set Athletics batterymates began in 1902. Needing a competent backstop to supplement Powers and to bolster a struggling staff, Mack obtained first Osee Schrecongost, then Rube Waddell. In Waddell’s first start on June 26, Mack paired him with Powers. Both were unimpressive in a 7-3 loss to Baltimore. Then Mack had Schreck catch Waddell against the same Orioles on July 1. A 2-0 victory, and a lasting union, resulted.

The onset of set Athletics batterymates began in 1902. Needing a competent backstop to supplement Powers and to bolster a struggling staff, Mack obtained first Osee Schrecongost, then Rube Waddell. In Waddell’s first start on June 26, Mack paired him with Powers. Both were unimpressive in a 7-3 loss to Baltimore. Then Mack had Schreck catch Waddell against the same Orioles on July 1. A 2-0 victory, and a lasting union, resulted.

Powers and Schreck split catching duties that season, as the Athletics won their first pennant. Eddie Plank led Mack’s staff with 32 starts. Powers started for 17 of these, Schreck 12, and Farmer Steelman (released when Mack grabbed Schreck) three. Bert Husting and Waddell came next with 27 starts apiece. Powers caught 26 of Hustings’ starts and Schreck caught 26 of Waddell’s. Snake Wiltse started 17 games, with Powers catching 13 of these. Fred Mitchell rounded out the top five in the rotation with 14 starts, Schreck catching all but two.

Over the 1903 and 1904 seasons, Schreck remained Waddell’s regular catcher, handling 80 of the left-hander’s 84 starts over these two seasons. Powers was now solidly aligned with Plank, lining up with this left-hander 73 of 83 times. Right-hander Weldon Henley started 55 games over these two years, with Schreck catching 37 of them. Powers started in 19 of Chief Bender’s 33 assignments in 1903, but Schreck caught 14 of the pitcher’s 20 starts in 1904.

Schreck and Powers remained relatively healthy from 1902 through 1904. Both were right-handed batters. Schreck’s offensive contributions slid from a 108 OPS+ with Philadelphia in 1902 to an 87 OPS+ in 1903, and then a 33 OPS+ in 1904. Powers’s OPS+ numbers fell too: 74 in 1902, then 53 in 1903, and 32 in 1904. There exists little evidence that the alignments between the two backstops and the staff were anything other than set batteries. In fact, when Mack replaced his starting pitcher during a game, he frequently replaced the pitcher’s catcher too, swapping out one battery for another.

Contemporary insights into these pairings were limited, with the colorful Schreck and Waddell grabbing what attention there was. In 1905 Timothy Sharp wrote of the pair: “The undisputed fact that Schreck is freakish or rather peculiar and it being conceded that Rube is mentally zigzaggy, no doubt establishes a bond of sympathy between these erratics.”4 Crude assessments aside, the whole was greater than the sum of its parts. “Schreck,” Mack’s biographer Norman Macht writes, “could prod [Waddell], scold him, cajole him, and get away with it.” Moreover, Schreck was particularly dexterous. “No matter how many times Rube crossed him up, Schreck caught the ball somehow, preventing many a wild pitch or passed ball.”5

Plank tested a catcher’s patience in another manner. One of the more deliberate pitchers of any era, he employed an elaborate windmill windup before cross-firing to the plate, the entire process sometimes beginning only after a maddening stalling pattern.6 Powers possessed the patience to handle Plank. Schreck, Macht notes, was one of the first catchers “to receive every pitch one-handed using a big pillow mitt,” an ability benefitting one catching the unpredictable Waddell.7 But there is no evidence suggesting Powers caught in this manner. Instead, he likely used his throwing hand nearby to his gloved hand. This technique may have permitted Powers to better frame Plank’s efforts, for the pitcher possessed fine control. Modern day studies8 prove the value of a talented pitch-framer, and there is no reason to believe, even absent video breakdowns and statistical models, this concept was lost upon Mack. Or Plank.

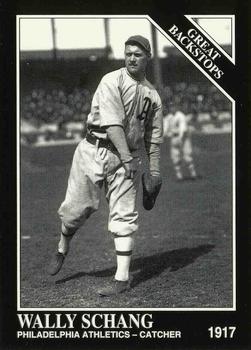

And what of Bender? In his career with Philadelphia, he was strongly aligned (75% or more matching starts) with a backstop in only four seasons: with Schreck in 1906, Ira Thomas in 1911 and 1912, and Wally Schang in 1914. Meaningful contemporary insights into these batteries have not been found.9 Conjecture might suggest the intelligent, resolute Bender was able to find a catcher who was valuable to him, but not overly dependent on any.

As Philadelphia drifted toward a second-division finish in 1904, Mack became increasingly frustrated with the light offensive contributions of Schreck and Powers. By the final month of the campaign, 22-year-old Pete Noonan replaced Powers. But even with Noonan, Mack paired him with a pitcher — 21-year-old Andy Coakley. The “colt battery” was featured in each of the pitcher’s eight starts in 1904.10 But Mack farmed out Noonan when the 1905 season began. Powers started the first ten games, but his offensive woes continued. Schreck was hitting again, eventually posting an OPS+ of 95 for the season, and soon eclipsed his peer. Powers broke his thumb in mid-June and, when he recovered, was expendable enough to be loaned to the Highlanders for a month. Consequently, in 1905, Schreck was the Athletics’ starting catcher in 107 of the team’s 152 games. Powers started for 23 of Plank’s 41 starts. Otherwise, the staff was aligned with Schreck.

Waddell sustained a shoulder injury on September 8, and started only once again, on October 7. He was then shut down for the World Series. In the Athletics’ losing cause against the Giants, Schreck caught Plank, Bender (Philadelphia’s sole victory), and Coakley in the first three games. Powers caught Plank and Bender in the final two games.

In 1906 Powers started each of Plank’s 25 starts, while Schreck started 30 of Waddell’s 34 starts, and 24 of Bender’s 27 starts. One rookie, fastball-curveball pitcher Jack Coombs, was mostly paired with Powers (11 of 18 starts). Another, spitballer Jimmy Dygert, was slightly aligned with Shreck (13 of 25 starts). These alignments held in 1907. But excepting Dygert (Schreck now starting 20 of his 28 assignments), they all weakened. During one midseason stretch, Powers was pulled off Plank’s assignments, and instead was placed in the lineup when Coombs started. The relative loosening of the set batteries likely reflected Mack’s search for success. Both catchers presented challenges. Schreck hit (his OPS+ over 100 in both 1906 and 1907) but drank. Powers was sober but did not hit (an OPS+ of 3 in 1906, 32 in 1907).

This transitional phrase accelerated in 1908. Waddell was sold before the season began. Young Syd Smith made 24 catching starts, the most yet by an alternative to Schreck and Powers, before proving a disciplinary problem and being dealt to the Browns for Bert Blue on August 2. By then, Philadelphia had fallen under .500. Blue, and newcomers Ben Egan and Jack Lapp, received tryouts in the closing weeks. Schreck was waived on September 23. Still, even amidst such change, set batteries characterized the squad. Rube Vickers led the team with 34 starts, with Schreck catching 25 of these games. Both Plank and Dygert made 28 starts, Powers starting 21 of Plank’s, Schreck 18 of Dygert’s.

Mack purchased Ira Thomas in the off-season. Powers helped pilot Plank to victory in the 1909 season opener but fell victim to intussusception and died two weeks later. Paddy Livingston was then purchased and emerged as the backstop of choice for spitballers Dygert and Cy Morgan, starting in 28 of the 39 games those pitchers started. Otherwise, despite missing four weeks mid-season and the final two weeks with injuries, Thomas was the default catcher for the staff. Philadelphia fell just short to Detroit for the pennant.

In 1910, Philadelphia took the flag. Thomas again battled injuries, but still emerged as the catcher-of-choice for Bender, Plank, and Harry Krause, starting 38 of the trio’s 71 starts. Livingston remained with Dygert and Morgan, starting 21 of the duo’s 42 combined starts. To locate his pitches, Coombs focused not upon the batter, but instead his catcher’s left shoulder.11 Because of this, he preferred the target provided by the 5-foot-8 Lapp and worked with that catcher for 26 of his 38 starts. Nonetheless, in the World Series against the Cubs, Thomas was paired with Coombs for the pitcher’s first two starts. Mack valued a veteran presence, and Thomas had performed well in the series opener, catching Bender.12 Two victories resulted, although Coombs was not at his best. With Lapp catching Game Five, he was, and the Athletics captured their first championship.

Finally, in 1911, Thomas avoided significant injury, and a more “natural” picture of the Philadelphia batteries in this era emerges. Lapp started 43 games, 34 of which coincided with Coombs’s 40 starts. Livingston started 18, 12 of which coincided with Morgan’s 30 starts. Thomas started in 23 of Bender’s 24 starts, 17 of Krause’s 19, and 28 of Plank’s 30. In Philadelphia’s World Series triumph over New York, Lapp caught Coombs twice; Thomas handled Bender three times and Plank once.

The Athletics faded to third place in 1912. Thomas again struggled with injuries and would soon be transitioning to a coaching role. Livingston was gone, with Ben Egan returning. Consequently, Lapp emerged as the club’s first-string catcher. But he was only strongly aligned with Coombs, starting 28 of the pitcher’s 32 starts. Bender retained Thomas, with the catcher starting in 15 of his 19 starts. Egan started in 15 (Lapp in 10, Thomas in five) of Plank’s 30 starts. Years later Lapp spoke of Bender being a crafty, unpredictable pitcher to catch, while the sudden drops of Plank’s offerings wreaked harm to his digits.13 Possibly the two veteran hurlers found Lapp less than an ideal partner as well.

Lapp batted left-handed. From 1910 through 1912, 15 (9%) of his 170 starting assignments occurred when the opposition started a left-hander. Philadelphia’s other catchers, over these three seasons, were all right-handed bats, and 73 (25%) of their 290 starts occurred versus opposing southpaws. During these years Mack did, to an extent, platoon his catchers based on the opposition. But he primarily platooned his catchers based on his own staff. Coombs faced left-handers in 19 games over this span, Lapp started in 11 of these matches. Lapp was often a stronger offensive option versus right-handers than the other catchers, but when Bender, Morgan, or Plank started against a righty, he usually remained on the bench.

Coombs was lost to injury early in the 1913 season, accelerating a rebuilding of the pitching staff already underway. Lapp suffered a throat injury in spring training, but played on, his OPS+ falling (from 153 in 1911, and 113 in 1912) to 85. Rookie backstop Wally Schang, who Mack fortunately landed in an off-season draft, benefitted from such opportunities, and contributed a 138 OPS+ in 1913. The two remained the principal backstops in 1914, and again Schang (137 OPS+) outdistanced Lapp (91 OPS+) in offensive production.

Schang was a switch-hitter. Across the 1913 and 1914 seasons Lapp started 137 games as a catcher, only 15 (11%) against southpaws. During this span, Schang started 149 games as a catcher, 79 (53%) against left-handers. Mack had begun to platoon his catchers more towards his opponent’s staff than towards his own. In 1913 and 1914, Schang was paired with Bender (36 of 44), Joe Bush (33 of 39), and Bob Shawkey (27 of 46). Lapp was aligned with Plank (starting in 31 of the pitcher’s 52 starts in these two seasons), Boardwalk Brown (30 of 42), Herb Pennock (11 of 17), and Weldon Wyckoff (16 of 27). These were relatively loose alignments, mostly as Lapp started only nine of the 32 games when one of these four pitchers faced an opposing left-hander.

Schang was a switch-hitter. Across the 1913 and 1914 seasons Lapp started 137 games as a catcher, only 15 (11%) against southpaws. During this span, Schang started 149 games as a catcher, 79 (53%) against left-handers. Mack had begun to platoon his catchers more towards his opponent’s staff than towards his own. In 1913 and 1914, Schang was paired with Bender (36 of 44), Joe Bush (33 of 39), and Bob Shawkey (27 of 46). Lapp was aligned with Plank (starting in 31 of the pitcher’s 52 starts in these two seasons), Boardwalk Brown (30 of 42), Herb Pennock (11 of 17), and Weldon Wyckoff (16 of 27). These were relatively loose alignments, mostly as Lapp started only nine of the 32 games when one of these four pitchers faced an opposing left-hander.

The Athletics reached the World Series both seasons, playing nine postseason games. Schang started each of Bender’s three starts, both of Bush’s two starts, two of Plank’s three starts, and Shawkey’s sole assignment. Lapp caught Plank once, in Game Two of the 1913 battle against the Giants. The Athletics lost the game, 3-0. When Mack went with Plank again in Game Five, Schang had emerged as an October star, and Lapp thereafter did not make any postseason starts.14

One might wonder to what extent other teams emulated the set batteries Mack employed. The 1914 data for the 15 other American and National League squads provides a snapshot. Seven teams had a clear primary catcher, without any other catcher aligned with a staff mainstay: the Browns, Giants, Naps, Pirates, Reds, Tigers, and White Sox. An eighth team, the Cardinals, had two catchers essentially alternate lead duties, but without any clear set batteries present.

Three teams had a single set battery standing out, to varying extents. Roger Bresnahan and Jimmy Archer divided duties for the Cubs, with a slight alignment (14 of 21 starts) between Bresnahan and pitcher Bert Humphries. Hank Gowdy was the Braves’ first-string catcher, but Bert Whaling caught 20 of Lefty Tyler’s 34 starts. In Washington, John Henry was the primary backstop, except in Walter Johnson’s 40 starts, when Eddie Ainsmith started 26 games (a total which would have been considerably higher had Johnson’s preferred batterymate not been out a month injured).

For another two teams, two set batteries were present. In Brooklyn, Lew McCarty was the first-string catcher, but Otto Miller was aligned with two of the three southpaws on the staff, starting in 11 of Frank Allen’s 21 starts, and 12 of Nap Rucker’s 16. With the Yankees, Jeff Sweeney and Les Nunamaker evenly divided duties, except for two strong alignments: Sweeney caught 20 of Ray Keating’s 25 starts, while Nunamaker started in 17 of Jack Warhop’s 23 starts.

Only with the Phillies and Red Sox were multiple set batteries present, as they were with the Athletics. Both teams had catchers as player-managers: Red Dooin in Philadelphia, Bill Carrigan in Boston. With the Phillies, Bill Killefer started 84 games, and was recognized as Pete Alexander’s partner, starting in 34 of the pitcher’s 39 starts. Ed Burns was the starting catcher for 14 of Ben Tincup’s 17 starts. And while Dooin only caught 34 times, 16 of these were when Erskine Mayer started. With the Red Sox, Carrigan handled the two leading left-handers on the staff, starting in 27 of Ray Collins’s 30 starts and 23 of Dutch Leonard’s 25. Hick Cady was the starting catcher for 12 of Rankin Johnson’s 13 starts. Pinch Thomas was the starting catcher for 16 of Rube Foster’s 23 starts. Carrigan had either Cady or Thomas receive Hugh Bedient, Ernie Shore, and Smoky Joe Wood. Of the trio’s 46 starts, the two junior catchers started 43 of these games.

For the Athletics, their dynasty abruptly ended as Plank, Bender, Eddie Collins, and Home Run Baker departed after the 1914 campaign. The franchise sank deep into the American League cellar for the next two seasons with a revolving door of mostly inexperienced pitchers and only slight trends toward set batteries. Such pairings began to re-emerge in 1917 as Billy Meyer caught 25 of Bush’s 31 starts while Schang handled the rest of the staff. Cy Perkins caught all of Scott Perry’s 36 starts in 1918; otherwise Wickey McAvoy was the primary backstop. By 1919, Perkins increasingly supplanted McAvoy, who nonetheless remained paired with Walt Kinney and Tom Rogers.

Mack’s set batteries passed with the Deadball Era.15 Beginning in 1920, Perkins, then Mickey Cochrane, commonly caught 130 games a season. Had the turmoil of the 1915-1919 staffs soured Mack on accommodating pitchers with specific batterymates?16 Did the game’s offensive revolution increase the value of an everyday catcher who could hit?17 Had coaching and training become increasingly standardized, making a catcher’s grooming individual pitchers less necessary?

Future research into such topics may allow baseball historians to better understand the full arc of set batteries over the sport’s history. Eventually, what was a universal concept from the sport’s infancy faded and fans came to recognize a “personal catcher” as an exception, a luxury afforded to a star pitcher.18 With the Philadelphia Athletics of 1901-1914, the concept of set batteries may well have been a very successful outlier on this continuum.

Acknowledgments

An earlier version of this article appeared in the June 2015 edition of The Inside Game, the newsletter of SABR’s Deadball Era Committee. A spreadsheet with data used in this study may be accessed at https://tinyurl.com/yao9lrez

This version was reviewed by Norman Macht and fact-checked by Chris Rainey.

Notes

1 Henry Chadwick, ed., Spalding’s Base Ball Guide and Official League Record for 1893 (New York: American Sports Publishing Company, 1894), 38.

2 Norman Macht, Connie Mack and the Early Years of Baseball (Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2007), 55, 112.

3 Peter Morris, Catcher: How the Man Behind the Plate Became an American Folk Hero (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2009), 208-228, 272, 358.

4 Timothy Sharp, “Exciting Finish,” The Sporting News, October 7, 1905, 2.

5 Macht, Mack and the Early Years, 277.

6 Macht, Mack and the Early Years, 246-248; Bill James and Rob Neyer, The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers (New York: Fireside, 2004), 344.

7 Macht, Mack and the Early Years, 277.

8 For modern-day overviews, see Ben Lindbergh, “The Art of Pitch Framing,” Grantland, https://tinyurl.com/m7zqqfq and Ben Lindbergh, “On the Margins: How Pitch-Framing Became More Important—and More Common—Than Ever,” The Ringer, https://tinyurl.com/y7mezrbo, accessed November 14, 2018.

9 What commentary on Bender’s battery relationships existed seemed to focus upon the peculiarities of the “Indian race.” To this end, see Billy Evans, “Superstition Rules Many Star Pitchers,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, November 13, 1910, 57.

10 Francis C. Richter, “Quakers Quips,” Sporting Life, December 31, 1904, 5.

11 Cincinnati Enquirer, August 31, 1911, 8.

12 The Cubs started two right-handers, Mordecai Brown and Ed Reulbach, against the Athletics in Games Two and Three, when Thomas caught Coombs. If anything, these matchups would have seemingly favored a left-handed bat like Lapp’s.

13 “Jack Coombs Led All in Endurance Powers,” The Sporting News, October 17, 1918, 5.

14 Again, as had been the case in the 1910 World Series, on the two occasions when Lapp did not start with an Athletics pitcher he had usually been matched up with during the regular season, it was not as an opposing left-hander was starting. In Game Five of the 1913 Series, Christy Mathewson went against Plank. In Game Two of the 1914 Series, Bill James went against Plank.

15 From 1920 onwards, to the extent Athletics batteries were distinguishable, they belonged to knuckleballers: Eddie Rommel with catcher Frank Bruggy from 1922 through 1924, and George Caster with Earle Brucker from 1937 through 1940.

16 In addition to the churn of untried arms, some of Mack’s veteran twirlers (notably Kinney and Perry) jumped to independent teams.

17 In the Deadball Era, Mack’s catchers usually batted eighth. Perkins and Cochrane moved well up in the lineup.

18 The term “personal catcher” seems to have first entered the sport’s lexicon in the late-1930s, describing Rollie Hemsley as Bob Feller’s catcher-of-choice. (See, for example, Charles P. McMahon, “Say Pytlak-Hemsley Feud May Provide Spark for Cleveland’s Pennant Drive,” Piqua Daily Call, April 4, 1939, 6.) By the late 1950s, the term began to appear in The Sporting News.