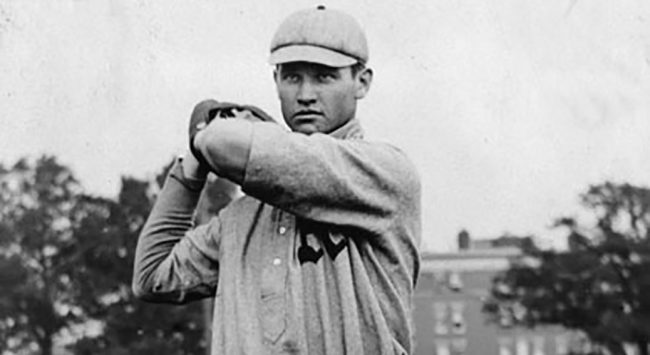

Weldon Henley

In the first decade of the 1900s, most major-league baseball players still originated from the northern United States and were not educated past high school. It was not especially common to find Southern college men on big-league rosters. Weldon Henley was one of the earlier such players to appear in the majors when he debuted for the Philadelphia Athletics in 1903. Though he was once praised as “the most promising youngster ever developed in a Southern college,”1 his career is not remembered much today – he was out of the majors after 1907. However, Weldon Henley’s name can still be found in baseball almanacs and history books by virtue of several firsts that he accomplished, including throwing the first no-hitter in the history of the Athletics franchise.

Weldon Henley was born October 25, 1880, in Jasper, Georgia, a town located about 50 miles north of Atlanta. He was the first of ten children for John W. and Catherine (née Netherton) Henley. John W. Henley was an educator but also practiced law, and he later reached the position of Assistant U.S. Attorney for the Northern district of Georgia. The Henley name is still familiar to some in the area because it is tied to the regional map he helped to create, the J.W. Henley Map of Pickens County, Georgia. A brother, John R., was a decorated veteran of the US Marines and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Weldon Henley grew up playing ball around Jasper before enrolling at the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta in 1898.2 Georgia Tech had been established only 13 years earlier, and Weldon almost instantly became the first star for their fledgling baseball program.

At 6-feet-2, the young right-handed pitcher towered over his Tech teammates, but his frame was gangly – he barely made it to 180 pounds in his playing days. He used a peculiar grip, holding the ball with his index and middle fingers but keeping his thumb tucked against his palm on every pitch, no matter the type.3 From time to time he would sneak in an underhanded delivery to keep batters guessing. He also threw a curveball that one enthusiastic Atlanta reporter claimed “geometricians have never discovered and put in the textbooks.”4 He almost singlehandedly raised the Tech club to a level of respectability, and he was named the team captain for both the 1900 and 1901 seasons. In 1900, he set a school record when he did not allow a single earned run the entire year, though he pitched just 30 innings that season at a time when college teams played only a handful of official games.

During the summer months after the school year ended, Henley played for various amateur teams across Georgia. Since he was a college student, he could not play for teams that were considered professional. But Henley was a known commodity in the region, and it would not be unreasonable to assume that teams occasionally paid him under the table when the pride of their town was at stake. In May 1901, accusations of professionalism from the Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Association were aimed at Henley for receiving pay for railroad fare to play in Elberton, Georgia, the previous summer.5 In response to the charges, the Elberton coach provided affidavits saying no money was exchanged. Henley pitched a final season for Georgia Tech, but the school’s athletic program was still temporarily blacklisted from the conference.6 (It was reinstated the following December.)

After Henley left Georgia Tech, the baseball program sank to mediocrity. After just a couple of years, however, the new football coach, John Heisman (of Heisman Trophy fame), pulled triple duty at the school and also took over the baseball and basketball programs.

With his college career nearing completion,7 Henley considered offers to play baseball professionally. A team in Selma, Alabama, headed by Ed Peters had joined the new Southern Association for its first season and tried to sign him.8 Peters thought he had a deal in place with Henley and planned to add him to the Selma roster in June after classes were over, but the pitcher backed out. Various accounts during the summer suggest that Henley’s family opposed him playing baseball professionally and instead wanted him to go to work as a civil engineer.

He continued to play amateur ball through the summer, though, suiting up for one of the top amateur teams in the South, the Memphis Chickasaws (not to be confused with Memphis in the Southern Association). In July, Jim Ballantyne, a catcher/first baseman for Nashville in the Southern Association, found that Henley was playing in the state. Ballantyne also happened to have been a coach with Georgia Tech the previous spring, and he convinced Nashville manager Newt Fisher to make an offer to the pitcher.9 Fisher eventually persuaded Henley to go professional and join the Volunteers. Though he had been recruited to finish the summer pitching for Nashville, he was traded in September and finished the season back in Memphis, this time playing for the city’s Southern Association team.

The 1901 season was supposed to be the only year of professional baseball for Henley, or at least that was the plan he conveyed to teams looking to sign him in 1902. He already had a more profitable job lined up to work as an engineer with a railroad company. But Ed Peters, who had relocated his Selma club to Atlanta over the offseason, took another shot at signing Henley. This time Peters offered an amount that convinced Henley to stick with baseball; he signed with Atlanta.

It was suggested by columnists later that Henley’s intentions to work could have been a ploy to get Peters to “convince” him to play baseball, noting how he similarly had to be convinced to play for Nashville the previous year. Even as a young rookie, Henley soon developed a reputation as a man “who looks after his business affairs.”10. According to one tale that came from Henley’s time in Atlanta, the young pitcher was not up to pitching one day and threatened to leave the team. Teammate Frank Wilson started in Henley’s place, willing to take on the extra work rather than risk having Henley walk away and thus losing $25 that he was owed from a card game.11

The Atlanta club did not have an official name, but newspaper writers often dubbed them as the Pretzels.12 This was common for teams featuring German names on the roster, but the moniker was especially appropriate for the Atlanta club. The lineup sounded like a beer list at a local tavern, including manager Ed Pabst and infielder Henry Busch. Teammate Jesse Hoffmeister unfortunately missed the founding of the Hofmeister Brewery by several decades. Frank Delahanty, one of the five professional baseball-playing brothers of Ed Delahanty, was also a teammate in Atlanta.

On April 26, Henley started the inaugural game for the team that would become the Atlanta Crackers, the long-standing minor league franchise that resided in the city before the Braves came along in 1966. The highlight of the season for Henley came on June 7, when he threw a no-hitter against Arkansas (who featured yet another Delahanty brother, Jim Delahanty).

As the year progressed, the major-league teams were hearing reports of a promising pitcher from the South. Nashville outfielder Hugh Hill was overwhelmingly considered the top performer in the Class B Southern Association during the season, but Henley was the top prospect in the league and received several offers to join major-league teams during the year. He finished out the season with Atlanta, ultimately winning 20 games there. Newspaper reports the following fall stated that Henley had come to agreement on a deal with John McGraw and the National League’s New York Giants. However, when November rolled around, it was also announced that he had signed a contract to join Connie Mack with the Philadelphia Athletics in the American League. With both teams staking a claim to the pitcher, Henley found himself in the middle of the baseball war between the two circuits.

The “war” was settled in January 1903, and as a result Henley was assigned to Philadelphia. This would have closed the matter, except he reportedly had also previously signed a contract to return to Atlanta, and new manager Abner Powell claimed to have already forwarded $300 to Henley for the upcoming season.13 Tim Murnane, a member of the Board of Arbiters for the minor leagues, was asked to intervene in the decision. Murnane had been a 19th-century major-leaguer, and, in addition to his arbitration role, he was a baseball writer for the Boston Globe, He also held the position of president of the New England League.14 He deemed that Henley was property of the A’s, and Henley achieved another first: the first Southern Association player to jump a contract.15

Henley went to spring training with the Athletics in Jacksonville, Florida, looking to compete with Charles “Chief” Bender and other rookies for a spot on the roster. A writer covering Philadelphia’s spring training reported back that Henley had been dealing with a lame arm early in camp, but that the young pitcher had “a great future before him if he uses his arm carefully.”16 Henley and Bender not only made the team, but they joined Rube Waddell and Eddie Plank to form the A’s starting rotation.

On April 23, he made his debut in Philadelphia’s fourth game of the season and became the first in what would become a long line of former Georgia Tech students to play in the major leagues. He topped the eventual AL champion Boston Americans, 7-4, striking out seven batters along the way. In addition to his curveball, he made use of a deceptive windup where he “swings the ball slowly and after it has passed over his head gives the impression that his arm will go further before the ball is delivered.”17

It was a solid introduction for the pitcher, but he had an up and down season from there. His delivery and curve ball had given Boston fits in that first game, but as the New York Sun stated after his third start at New York, his delivery “was awesome to look upon, but the bark … was worse than the bite.”18 Henley’s ERA sat at 5.19 after four starts.19 It was helped, however, by a 10-inning shutout against the Yankees on May 30. Henley battled wildness all season. He led AL rookies with 67 walks and finished fifth overall in the league by hitting 12 batters. He was effective against better ballclubs, posting a .545 winning percentage against teams with winning records, and he ended his season with 12 wins and 10 losses. He helped the Athletics to a second-place finish in his first season, but Charley Bender, with his 17-14 record, ended up being the prize rookie for the team.

The Athletics placed Henley on their reserve list for 1904 and he got a head start on training that winter in preparation for the upcoming season. In January, he joined a couple of fellow Georgia athletes, jockey George Odom and world-class bicyclist Robert Walthour, in an early training session in Atlanta. He took some time off from training at the end of the month to wed the former Blanche Simmons, also of Jasper. The Henleys had barely finished their honeymoon before Weldon joined John McGraw and several major league players in Hot Springs, Arkansas, for an early training camp. Next, he returned to Atlanta to help coach the Georgia Tech baseball squad for their season, before finally heading to Spartanburg, South Carolina, to join the Athletics for official spring training.

Despite all the effort he put into training for the season, or possibly because of it, Henley still had reports of arm soreness before the season.20 An exhibition loss to Princeton was not a great start, and 1904 would be an up and down season. Game reports throughout the year were sprinkled with mentions of wildness, but when he put it all together, he could pull off masterful games. He threw five shutouts during the year (finishing tenth in the league) and, in all but one of those, he allowed four hits or less. Henley did make some efforts to increase his effectiveness during the season. He experimented with the spitball that was gaining popularity and tried an early version of a rosin bag that contained powder from the pine trees of his home region of North Georgia. He finished the season with a losing 15-17 record in 36 games for the fifth-place A’s, but he also had a respectable 1.08 WHIP.

The Athletics wrapped up spring training in 1905 by making a stop in Atlanta for an exhibition game. Several friends and family, including coach Heisman, came out to cheer on their native son. Henley defeated Nap Rucker and the Crackers 9-4 in that game, but then in the regular season he lost five of his first six decisions. Henley pitched only twice during the month of June. Little was reported in newspapers on his status at the time, so he could have been dealing with injuries during this period. There was one mention of him getting only to first on a long hit to the rightfield fence “owing to lameness.”21 Or the layover could have instead arisen from his ineffectiveness over the previous month. In any case, he was back in the starting rotation in July.

Henley’s record stood at 2-7 on July 22, when he took the mound in the first game of a doubleheader in St. Louis against the Browns. He hadn’t pitched in nine days but on that day, Henley seemed “to have been born anew, his repertoire comprising all of the mysterious and occult features that made him one of the blazing comets of the baseball firmament” the previous season.22 Only three batters made it to first base, all by bases on balls, and no runner made it to second base. The fans in St. Louis rose to their feet cheering for the opposing pitcher Henley as the last out of the game was made, for they had just witnessed only the fifth no-hit game in the short history of the American League, the first ever for the Philadelphia Athletics.

The no-hitter was one of the top pitching feats of 1905 and sealed Henley’s place in baseball history. Overall, though. his season was a disappointment. He otherwise continued battling wildness and won only four games for the pennant-winning Athletics. The team’s regular starters may have been overworked heading into the World Series, but Mack didn’t risk using Henley. Instead he chose to have starters Plank, Bender, and Andy Coakley each pitch complete games in the five contests against the Giants (Waddell was famously unavailable for the series).

Henley did have one additional win that year, but it would not appear in his stats for the Athletics. The Pennsylvania towns of Berwyn and Ardmore are situated about 10 miles apart on the outskirts of Philadelphia. The teams for each town were set to renew a heated rivalry on August 5, 1905, with a spot at the top of the Main Line League standings on the line, not to mention the wagers of fans throughout both communities. When the Berwyn team sent their new pitcher to the mound, the Ardmore club immediately recognized him to be a ringer. Weldon Henley had just pitched the day before for the Athletics and was not scheduled to pitch again for a few days, so he had a day open to take the mound for the Berwyn team. The Ardmore contingent was up in arms over the ploy, but then surprisingly they got to the hired gun for three runs in the first inning. Henley settled in, though; he struck out 14 Ardmore batters and ultimately won 7-4.

Appearances such as Henley’s were not unheard of at the time. The idea could conceivably have come from teammates Rube Waddell and Osee Schrecongost, who helped Rollins College beat rival Stetson two years previously. Ardmore would even repeat the tactic later that year. Looking to gain revenge in their next game with Berwyn, they trotted in a ringer of their own, Washington pitcher Babe Adams (Adams tossed a complete-game shutout).

Inability to find the strike zone continued to trouble Henley at spring training for the 1906 season. He was wild in exhibition games, including an outing on April 8 against Newark of the Eastern League, in which he gave up 10 walks, hit two batters, had a wild pitch, and added some wild throws on defense, all within six innings. Henley made the Athletics’ roster when camp broke in April, but before appearing in a regular-season game Mack tried him in one more off-day exhibition game against the Yankees. The game, played on April 29, was set up to raise funds for victims of the San Francisco earthquake. Henley was shelled for nine runs in three innings off eight hits, including a home run and three triples. Five days later Mack released Henley to Rochester of the Eastern League. Until recent research uncovered a no-hitter pitched by Pete Dowling in 1901, Henley had long been credited as the first major-league player to throw a no-hitter then not win a game at the top level the next season.

The demotion to the Class A Eastern League helped get Henley back on track. He had an 11-9 record for the Bronchos, and his performance got him back to the majors. In September, the Brooklyn Superbas selected him in the minor-league player draft (which later became the Rule 5 draft). Among Brooklyn’s other draft selections was another pitcher from Georgia with whom Henley was already familiar: former opponent Nap Rucker. Henley and Rucker were to be teammates in the spring, but before that, they faced off for a second time in an exhibition game, this one in Atlanta on December 1. The winter game was put together to experiment with a new pneumatic baseball manufactured by the Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. Instead of a typical rubber core, it had a core of compressed air. The new baseball never caught on, but the game may have provided a chance for a young player from Augusta, Georgia, to display his talents before going into his first full season: Ty Cobb was listed in the lineup for one of the teams.23

A salary holdout delayed the start of Henley’s 1907 season until May. He then made only seven appearances for Brooklyn, losing five of his six decisions, and was released back to Rochester in July. His only victory with Brooklyn was a 14-inning complete game effort against Boston on May 30.

Henley did have occasional bright spots with Rochester. He had an Eastern League season-high 12 strikeouts in a July 4 game against Toronto in 1907 and a one-hit shutout against Newark in August 1908, but he was starting to devote more time to interests outside baseball. In the offseason he ran a lumber mill in Marianna, Florida, where he and Blanche had relocated. In 1905, Weldon and Blanche had daughter Frances Katherine. Their son, Weldon Jr., followed in 1911 (Weldon Jr. later played in some amateur circuits and part of a season in the minor leagues).

Before the 1910 season, Henley notified Rochester that he would be late for camp due to pneumonia. It was likely, though, that he had no intention of returning to the team. Letters from Henley to the team suggested that he might be too weak to join Rochester at all during the year.24 In June, he was spotted pitching for amateur teams in Georgia and in Florida.

Several factors possibly contributed to Henley’s career stalling out before he even turned 30. Nearly 40 years after Henley retired, a former minor-league opponent from Georgia named Dick McIntosh recollected that Henley “was a great pitcher, but he wore himself out too early getting a little lax with the training rules.”25 But in the end, it may have been that Henley just had better opportunities in business.

After 1910, Henley seemingly quit as an active player.26 He moved into sales in industrial refrigeration, which was a burgeoning business in the South. The decision was a profitable one. The Henleys became a somewhat prominent family in the 1920s in Palatka, Florida, where they had come to reside. They were often mentioned in the social section of the local newspaper.

In 1932, however, Henley found himself in Florida newspapers for another reason. He was accused of trying to obtain money under false pretenses during a business deal to provide equipment for an ice factory. The charges were later dropped, and apparently the incident did not have any adverse effects on his reputation – he was later elected to the Palatka City Commission.

Though he had hung up his spikes in the 1910s, Henley remained active in baseball for years after. For a time in the 1950s he was the director and part owner of the Palatka Azaleas, a minor-league team in the Florida State League, and he helped bring minor-league teams to the city for spring training. He also occasionally made appearances at events in Florida with other former major league baseball players living in the state.

On November 16, 1960, five years after the death of Blanche, Weldon Henley Sr. passed away at the age of 80 after dealing with a long illness. He was laid to rest at West View Cemetery in Palatka.

Acknowledgments

Amanda Pellerin with the Georgia Tech library provided access to the school’s digital database and assisted with information on the Georgia Tech classes of 1898 to 1901.

Dan Pool at the Pickens County Historical Society provided information on the J.W. Henley Map of Pickens County, Georgia.

This biography was reviewed by Bill Lamb and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Terry Bohn.

Sources

In addition to the sources shown in the notes, the author used Baseball-Reference.com, Newspapers.com, Ancestry.com, ChroniclingAmerica.loc.gov, and the LA84 Digital Library Collections.

He also used:

Bevis, Charlie. “Tim Murnane,” SABR BioProject.

Darnell, Tim. The Crackers: Early Days of Atlanta Baseball (Athens, Georgia: Hill Street Press, LLC, 2005).

Gomes, Gene. “Abner Powell,” SABR BioProject.

Hanft, J.D., The Early Days of Baseball in Berwyn and Vicinity. Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society Digital Archives. https://tehistory.org/hqda/html/v11/v11n2p031.html

O’Neal, Bill, The Southern League: Baseball in Dixie, 1885-1994 (Austin, Texas: Eakin Press, 1994).

Sugar, Bert and Kent Samelson, The Baseball Maniac (New York: Sports Publishing, 5th ed., 2019).

Pickens County Georgia Genealogy Trails. http://genealogytrails.com/geo/pickens/schools.html

SABR Minor League No-Hitters Database

Notes

1 “No Tail-Enders Are Winners,” Chattanooga News, March 19, 1902: 2.

2 Georgia Tech is incidentally the alma mater of the author.

3 “Notes of the Diamond,” Nashville American, June 24, 1902: 6.

4 “Techs Lose Game Through Errors,” Atlanta Constitution, May 11, 1901: 12.

5 “Charges Against Players,” Atlanta Constitution, May 9, 1901: 7.

6 “Colleges Under Ban Are All Reinstated,” Nashville Banner, December 23, 1901: 2.

7 Henley may have been eligible to play another season at Georgia Tech, the school could not find records showing that he officially graduated.

8 “Sporting Notes,” Nashville American, July 24, 1901: 6.

9 “Nashville’s New Pitcher,” Nashville American, July 28, 1901: 6.

10 “Short Baseball Stories,” Joliet (Illinois) Evening Herald, February 12, 1907: 5.

11 “Short Baseball Stories”

12 Baseball-Reference.com and some other sources show that the team was also called the Firemen. This name may actually reference a charity game played by local firemen in August of that year. There was also a popular Hand Ball team in Atlanta known as the Firemen.

13 “Sporting Notes,” (Fall River, Massachusetts) Globe, February 2, 1903: 6.

14 E. C. Bruffey, “Henley Dispute to Be Settled,” Atlanta Constitution, March 24, 1903: 7.

15 “Henley Hard Hit,” Sporting Life, May 23, 1903: 5.

16 “Mack’s Twirlers Show Form and Make Things Hum,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 17, 1903: 10.

17 “Mackites Now Enjoy Weather of Right Kind,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 6, 1903: 10.

18 “In the Baseball World,” (New York) Sun, May 6, 1903: 7.

19 The ERA listed is approximate. The stat was not officially tracked until 1912.

20 “Athletics Pack Up for Trip North,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 30, 1904: 10.

21 “Murphy Made Rare One-Hand Catch; Athletics Won,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 20, 1905: 10.

22 “Browns and Athletics Break Even, Henley Pitching No-Hit Game,” St. Louis Post Dispatch, July 23, 1905: 19.

23 “Baseball Game in December,” Atlanta Constitution, December 2, 1906: 1.

24 “Ragon to Join Squad After Northward Trip is Begun,” (Rochester, New York) Democrat and Chronicle, March 31,1910: 19.

25 Henry Vance, “The Coal Bin,” Birmingham (Alabama) News, October 9, 1946: 13.

26 Through the years Weldon Henley was sometimes misremembered in news accounts as being Clarence “Cack” Henley, who pitched until 1915 and won over 200 games in the Pacific Coast League.

Full Name

Weldon Henley

Born

October 25, 1880 at Jasper, GA (USA)

Died

November 16, 1960 at Palatka, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.