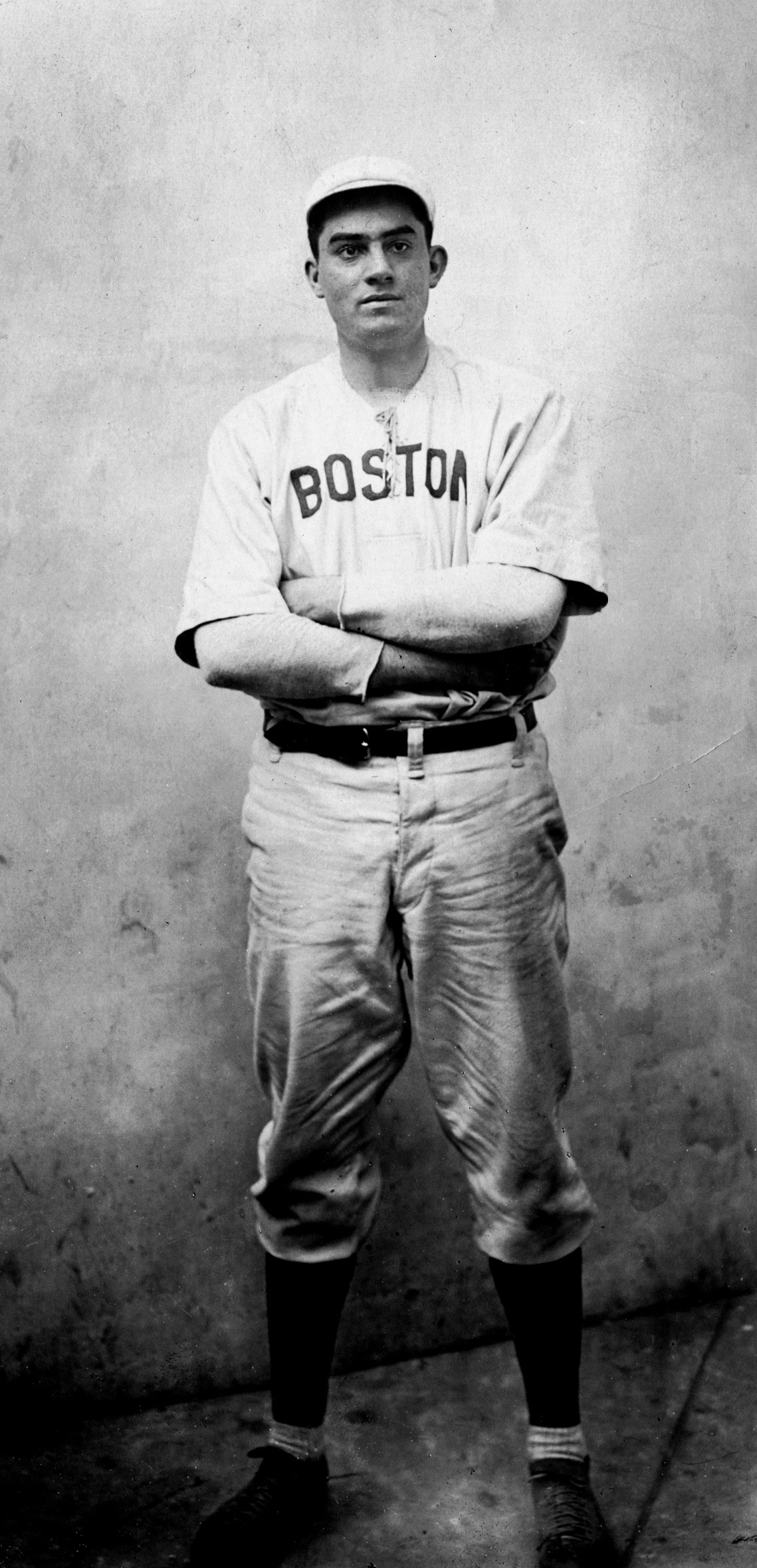

Ray Collins

Ray Collins might have been on his way to the Hall of Fame but for an abrupt and mysterious end to his career after only seven seasons. In 1913-14 he won a combined 39 games for the Red Sox, and his lifetime 2.51 ERA is impressive even for his low-scoring era. Collins was a good hitting pitcher and an outstanding fielder, but the key to his success was his remarkable control. He consistently ranked among the league leaders in fewest walks allowed per nine innings, finishing third in the American League in 1912 (1.90), second in 1913 (1.35), and fourth in 1914 (1.85).

Ray Collins might have been on his way to the Hall of Fame but for an abrupt and mysterious end to his career after only seven seasons. In 1913-14 he won a combined 39 games for the Red Sox, and his lifetime 2.51 ERA is impressive even for his low-scoring era. Collins was a good hitting pitcher and an outstanding fielder, but the key to his success was his remarkable control. He consistently ranked among the league leaders in fewest walks allowed per nine innings, finishing third in the American League in 1912 (1.90), second in 1913 (1.35), and fourth in 1914 (1.85).

Though big for his time (6-feet-1, 185 pounds), the Colchester farmboy did not throw hard. “Ray Collins hasn’t a thing,” said Hall of Fame manager Clark Griffith at the height of the Vermonter’s career, “yet he is one of the best pitchers in the American League – one of the two or three best left-handed pitchers in the business.” Hugh Jennings, another Hall of Fame manager, concurred: “I class him as the best left-hander in the American League, with the possible exception of Eddie Plank.”

When Collins’s major-league career was cut short in 1915, he returned to his native Colchester and struggled to eke out an existence as a dairy farmer for 42 years. Though he never made it to Cooperstown, Ray Collins was an original inductee of the University of Vermont’s Hall of Fame on October 10, 1969, and the Vermont Department of Historic Preservation honored his memory with the erection of a roadside historical marker at the Collins farm on July 19, 1998.

Collins wasn’t kidding when he listed his nationality as “Yankee” on a Baseball Magazine survey he filled out in 1911. A ninth-generation descendant of William Bradford, second governor of Plymouth Colony, Collins was also the great-great-grandson of Captain John Collins, purportedly one of Ethan Allen’s Revolutionary War Green Mountain Boys. One of Burlington’s original settlers, Captain Collins arrived from Salisbury, Connecticut, on August 19, 1783, and built the first frame house in town. Ethan Allen stayed with the Collins family while building his own homestead.

The 375-acre Collins farm on Route 7 in Colchester, originally purchased by Charles Collins in 1835, was where Ray Williston Collins was born on February 11, 1887. His family moved around a lot when he was a youngster, renting farms in other parts of the state, but his father, Frank Collins, still owned the Colchester farm. It was small and wet so he rented it to others. Around 1894 the family returned to the Burlington area and purchased land in the Intervale, an area of rich farmland along the banks of the Winooski River. There, on one of the largest farms in Chittenden County, the Collinses raised a herd of Jersey cows. The brick farmhouse still stood in 2010, just down the embankment from the former site of Burlington’s Athletic Park.

For a while Ray had an idyllic childhood. “Played ball today” is by far the most common entry in the journal he kept during childhood. He also went to University of Vermont baseball games. But when Ray was 10 his father died of scarlet fever. Ray’s mother, Electa, was forced to sell the Intervale property and move into a house in Burlington.

Electa Collins not only survived but prospered, buying and improving lots and selling them at a profit. She rented out the farm in Colchester, where Ray helped with the haying when it didn’t interfere with his studies. Later he worked as a conductor on the trolley that ran from Burlington through Winooski and out to Fort Ethan Allen.

Ray’s best buddy growing up was Dwight Deyette. The pair once jumped off the railroad bridge over the Winooski River together. Both attended Pomeroy School and later Edmunds High School, where Ray was captain of the tennis, basketball, and baseball teams. He didn’t play football in high school because his mother wouldn’t let him, even though he was considerably larger than most boys his age.

Collins often recalled his time at the University of Vermont as the four greatest years of his life. Though he lived at home, Collie joined the Delta Psi fraternity and got involved in campus social life. Among other activities, he served as committee chairman of the Kake Walk, a midwinter minstrel show that was banished from campus in the 1960s when it fell out of step with changing racial values. Ray also put his wide-ranging athletic talents to use, playing center on the varsity basketball team as a freshman and varsity tennis as a sophomore.

Ray’s greatest accomplishments, of course, came on the baseball diamond. In Vermont’s home opener on April 17, 1906, the first baseball game ever played at Centennial Field, freshman Collins batted safely twice and pitched a complete game, allowing only one earned run.

The crowning achievement of Ray’s freshman year came against Williams at Centennial Field on May 19. The Williams squad entered the game with just one loss, having ruined their undefeated record at Dartmouth the day before. Larry Gardner drew a leadoff walk in the first inning and scored what turned out to be the game’s only run. Entering the ninth, Collins was pitching a no-hitter and had not walked a single batter. With two outs, a Williams batter singled cleanly to right field, but when the runner was thrown out stealing moments later, Ray was carried off the field on the shoulders of his schoolmates.

Gardner received many accolades for his role on a team that finished 9-8, but the real hero was Ray Collins. Drawing all of the tough pitching assignments, Collie finished with a 4-3 record and an ERA of 0.70, striking out 36 and giving up only 43 hits and 10 walks in 64 innings. He earned honorable mention on the Springfield (Mass.) Republican’s All Eastern and All New England teams.

During his sophomore year of 1907, the Vermont team improved its record to 11-6 and that year’s class yearbook, The Ariel, praised Ray’s performance as “second to that of no college player in the country.” By that time his prowess had attracted the notice of major-league scouts. The Boston Red Sox followed him throughout the season, and toward the end a New York Highlanders scout offered Collins $3,000 to play from July through October. According to the Burlington Free Press, “on the advice of older men, Collins has declined the tempting offer, believing that he is yet too young to take up base ball in the fastest league in the world.”

The previous summer Ray had played in the Adirondack Hotel League for a team sponsored by Paul Smith’s Hotel on Lower St. Regis Lake. A brochure found among his papers boasted that “[t]he Paul Smith’s Baseball nine have always been champion of the Adirondacks.” During the summer of 1907 he pitched for semipro teams in Massachusetts, then joined his university teammates in playing for Newport, New Hampshire, of the Interstate League. In one game he struck out 21 batters.

That July, through some odd twists and turns, Collins and his teammates played a brief but full-fledged professional baseball stint in the Class D Vermont State League. When several of the original clubs dropped out, the university nine stepped in as replacements. “Many have felt all along that the Vermont team was the one to uphold the Burlington end on any baseball proposition, made up as it is of so many local favorites,” the Free Press wrote. In his first minor-league start, Collins pitched a shutout against first-place Barre-Montpelier, snapping that club’s eight-game winning streak. “Nothing like the pitching of Collins has been seen at Intercity Park since the days of Reulbach,” wrote the Montpelier Evening Argus. The collegians fared well during their short stint in professional baseball, holding the second best record (4-3) when the league disbanded for good on July 27.

With still a month to play that summer, Collins joined the Bangor Cubs of the Maine State League. In his first game, on July 30, he pitched a four-hit shutout against a Portland club called Pine Tree. A Portland sportswriter wrote that Ray’s windup resembled an “explosion in a leg and arm factory,” while a Bangor scribe wrote:

Collins is a tall, slim young feller from Burlington, Vermont, and is first string man on the University of Vermont team. This university is famous for the ball players it turns out, among whom may be mentioned Reulbach of the Chicago Cubs, and Collins seems to ably sustain the reputation of the university. He has all kinds of speed, curves and shoots, change of pace, good control, and a corkscrew delivery which is enough to scare a batsman away from the plate. Added to these important details, he has all kinds of confidence and a snap that keeps a game a’going.

Ray finished out the season with Bangor and led the Cubs to the 1907 Maine State League pennant. In his last appearance of the season, at the Eastern Maine State Fair on August 30, he pitched both ends of a doubleheader, defeating Portland 11-2 and 5-4 in ten innings – a harbinger of his greatest day in the majors seven years later.

Vermont finished with a disappointing 9-7 record in 1908, the last year both Collins and Gardner played for the varsity. Still, the season had its share of highlights, like the time Collins beat Holy Cross 1-0 and drove in the game’s only run with a triple. Students celebrated the victory in traditional fashion by going downtown and staging a mini-riot:

Shortly after the game the chapel bell began to ring, summoning the faithful to gather on the campus. About 200 students responded to the call, most of them provided with the night shirt prescribed for such occasions. Forming in line in front of the mill, they marched to the president’s house, where continued cheering brought President Buckham out to make a short speech. The march was then taken up down Prospect Street and to Brookes avenue to the home of Collins, the successful pitcher. After giving rousing cheers, the students continued down town to the club rooms of the Eagles, where they [were] joined by the band. Pitcher Collins was captured and borne on the shoulders of the advance guard as far as the foot of Church Street. The line then marched down to the Van Ness house where the Holy Cross team was supposed to be. Upon finding that the team was being entertained by the Knights of Columbus, the boys marched up the street and gave lusty cheers in front of their club rooms. On the return march to the college, some little trouble was experienced with the police over possession of various signs that had taken a place in the line of march.

The students in their ardor crippled temporarily the trolley service of Pearl Street. The trolley pole on a car was pulled from the wire at the corner of Pearl and Church streets and in front of the Howard Relief hall an attempt was made to block an Essex car; but the motorman applied the juice and the students, deciding that they would be the worse for wear in the encounter with the moving car, cleared the track. The trolley pole on another Pearl street car coming down the hill from Winooski was pulled from the wire and in the mix-up a window was broken, the splintered glass cutting the conductor, George Rogers, although not seriously injuring him. On the march up Pearl Street, the large bill board at the corner of Prospect Street was taken down and borne in solemn procession by some 60 students to the campus. Here a number of tar barrels were added to the stock of combustibles and an old-fashioned bonfire and war dance took place. After the fire died down the students gradually dispersed.

Following the close of the season, Collins was elected captain for his senior year. Gardner decided to forgo his last season of eligibility, instead signing with the Boston Red Sox, but Ray shunned offers to turn professional. “The president of the Red Sox team of Boston worked hard to land Collins,” the Free Press reported, “but the college boy, who has one more year at Vermont, decided to pitch college ball for the team of which he was recently elected captain.”

Collins received a large increase in pay – reportedly $185 per month – to return to Bangor for a second summer in 1908. This time he brought with him his college catcher, Marcus Burrington of Pownal, Vermont. Combining with Ralph Good, a Colby College star who later pitched two games in the majors with the Boston Nationals in 1910, Ray led Bangor to its second straight Maine League pennant. In appointing him to its 1908 All-Maine team, one Maine newspaper called Collins the “premier twirler of the league this season, as he was the last.”

Despite returning only five veterans, the 1909 Vermont team survived and even improved without Larry Gardner, posting a record of 13-9. Captain Collins pitched well throughout the season, but never better than in his last game for Vermont, on June 18. Going out in a “blaze of glory,” according to the Free Press headline, Ray struck out 19 and beat a tough Penn State team, 4-1. It was a fitting end to an incredible college career in which he won 37 of the 50 games he started, surpassing Bert Abbey, Arlie Pond, and Ed Reulbach as the greatest pitcher in UVM history.

After the season Ray received offers from eight of the 16 major-league teams. He decided to follow in Gardner’s footsteps and, shortly after the Penn State game, went down to Boston and came to terms with Red Sox president John Taylor. “That day I saw my first major-league game,” he remembered years later. “The Red Sox were playing the Tigers and Ty Cobb stole second, third, and home.”

Collins returned to Burlington for Senior Week. He served as marshal at the baccalaureate sermon, then carried the class banner at commencement on June 30, leading a procession of 73 undergraduates (including Larry Gardner) down the aisle of Burlington’s Strand Theatre. After handing out the various degrees (Collins received a B.S. in economics, as did childhood friend Dwight Deyette), President Buckham called on Ray to close the ceremony with a speech on behalf of the graduating class.

As part of his deal with the Red Sox, Collins received permission to remain in Burlington and pitch an exhibition game commemorating the 300th anniversary of Samuel de Champlain’s 1609 discovery of Lake Champlain. The games were part of Tercentenary Week, which included Vermont’s first-ever marathon (104 times around the oval track surrounding Centennial Field), featuring 1908 Olympic champion Johnny Hayes; a wrestling match involving Burlington’s own Fritz Hanson, champion welterweight of the world; Colonel Francis Ferari’s trained wild animal arena and exposition shows; and a re-enactment of the Battle of Lake Champlain on a man-made island in Burlington Harbor, attended by President Taft and the French and English ambassadors to the United States. In the opening game, as 50,000 visitors flooded into Burlington, Collins held an independent team from Pittsfield, Massachusetts, scoreless for nine innings, but the opposing pitcher was equally stingy. Each team scored once in the tenth, but in the 13th Collins’s run-scoring single gave Burlington the 2-1 victory.

Ray Collins left Burlington on July 12, 1909. He first went to Boston, then caught up with the team on a road trip. On July 19, with the Red Sox down 4-0 to Cy Young after three innings at Cleveland, Boston manager Fred Lake figured it was as good a time as any to test out his acclaimed rookie. In five strong innings of relief, Ray yielded two unearned runs and even singled in his first big-league at-bat. This game is best remembered as the one in which Cleveland shortstop Neal Ball made the first unassisted triple play in major-league history. It may also be the only time three Green Mountain Boys of Summer played for the same team in a major-league game: In addition to Collins, both Amby McConnell and Larry Gardner appeared in the Red Sox lineup.

Four days later, on the 23rd, Ray was the starting pitcher against the hard-hitting Detroit Tigers. Though he lost 4-2, he twice struck out the dangerous Ty Cobb. Collins was given a second chance to beat the Tigers on July 25, 1909. Pitching on only one day’s rest, Ray tossed the first of his 19 shutouts in the majors. It was a three-hitter, and all three of the hits were made by Hall of Famer Sam Crawford. Collins pitched only sporadically during the rest of the 1909 season, going 4-3 with an ERA of 2.81, but he had proved that he was capable of competing in the majors without any minor-league apprenticeship. As if to prove the point, after the regular season Ray matched up against the great Christy Mathewson on October 13 and defeated him, 2-0, in an exhibition game against the New York Giants.

Collins became a regular in the Boston rotation in 1910. In his first full season in the majors, the 23-year-old pitched a one-hitter against the Chicago White Sox and compiled a 13-11 record, making him the second-winningest pitcher on the Red Sox. His ERA of 1.62 was sixth best in the American League. He became a fan favorite at the Huntington Avenue Grounds, as demonstrated by the following clipping from the Boston Evening Record’s Baseball Chit-Chat column:

Ray Collins is a star. He is the idol of all the lady fans, those bewitching young women, who coyly gaze from under piles of feathers and ribbons. Is it any wonder that he pitches wonderful ball when those brown and blue and gray and violet orbs are on him? Gee, it’s great to be a big, fine pitcher. If I ever have a son that’s him, a pitcher and of course he will be a dashing fine chap. Fond expectations.

In February 1911 Tim “The Silver King” Murnane, a jovial, white-haired ex-major leaguer of the 1870s who had become baseball editor of the Boston Globe, came to Burlington to visit Ray Collins in his hometown. The following is an excerpt from the column he wrote about that visit:

In looking over the list of Boston Red Sox players still in love with their surroundings, living within a day’s ride of Boston, I selected Mr. Collins as the player on whom to make a friendly call and wired the young man that I was coming up to see him. I had also intended calling on Larry Gardner, who winters at Enosburg Falls, about 50 miles farther north, but our signals became crossed and to my surprise Mr. Gardner was on hand to greet me on my arrival at Burlington, where he has many friends as the result of his student days at the University of Vermont, where he, like Collins, was a valuable member of the baseball team.

I was soon tucked away in a roomy sleigh and started for Mr. Collins’ home, 10 minutes ride from the business section of the city. “I would like to have you see mother” was all the comment that the ball player made as we went slipping over the snow. “This is my home,” he remarked as the team drew up in front of a pretty house on a residential street with a grade just right for fine sledding. Before entering the house the camera man snapped a picture of the player and the writer, and Ray pointed to a field close by, saying: “There is where I learned to play ball as a schoolboy. About all that is left to remind me of the old place now is that elm tree.”

I was introduced to Mr. Collins’ mother as “Mr. Murnane of the Boston Globe” and was informed by the lady that she always has read the Globe baseball news since Ray took up the game as a serious matter.

“Ray always loved to play baseball,” remarked Mrs. Collins. “When at the primary school he was captain of a team, later at the high school, and finally during his four years at college he kept up his enthusiasm for the game, so I was not surprised to find that he was willing to take a position with the Boston Americans. I never tried to influence my boy to give up the game that he seemed to love so much and his success in which made so many friends for him.

“Ray seldom talks baseball, however, but loves to bring home the pictures of young men he has played with.” This was very evident after a glance at his interesting den, where the green and gold colors of his alma mater were the principal decoration, with pictures of baseball parks and Red Sox players strewn around.

We then went for a sleighride around the city, with the ball player handling the ribbons. As we slipped through the main streets it was a continual “Hello, Ray.” Everyone in the place seemed to know the player. Collins simply recognized the salute with a “Hello” in each case.

That evening I sat down to supper with the good Mrs. Collins and the pride of her heart. For the first time Ray mentioned baseball. We chatted about the Red Sox players and about the splendid treatment the boys received on their visit to Vermont last fall. Mrs. Collins said she had enjoyed a call from Tris Speaker and other players of whom she had read and had a great desire to see.

The delightful simplicity of the woman, and the good taste displayed in the home, made it quite easy to understand why Ray Collins is modest at all times and deeply considerate of every man’s feelings.

It is said that in springtime a man’s thoughts turn to love and baseball. So it was that during spring training in 1911, while the Red Sox were working out in Redondo Beach, California, Ray Collins became smitten. Her name was Lillian Marie Lovely, and it is said that her surname suited her well. She was the 18-year-old sister of Jack Lovely, one of Ray’s fraternity brothers who later headed the Jones & Lampson Company, the largest gear factory in Springfield, Vermont. Jack’s family had recently moved from St. Albans to Los Angeles, and Jack insisted that Ray meet them while he was out there.

Ray apparently left his heart and his concentration in California. He was 3-6 at one point in the 1911 season, prompting rumors that he was soon to be released. “Ominous rumblings agitate the atmosphere,” wrote one poetic scribe. “The management holds, apparently, that a player who cannot pitch nine games and win, say, 15 or 20, is useless, dangerous and ought to be abolished.” But before management did anything rash, Ray turned his season around, finishing at 11-12 with a 2.40 ERA.

During the offseason Ray married Lillian in Los Angeles. In a congratulatory note, Red Sox president James McAleer wrote, “May you live long and prosper and have a million little Collinses. . . . I think you are due for a great year and Mrs. Collins will be proud of her big boy when the season is over.” The couple set out as though they were taking McAleer’s blessing of fertility at face value – their first daughter, Marjorie, was born in December 1912. Four more followed: Ray Jr. in 1914; Janet in 1916; Warren in 1919; and Dorothy in 1923.

During their first winter together Lillian may have made life too comfortable for her new husband. Ray was noticeably overweight when he reported for spring training at Hot Springs, Arkansas, and his problems were compounded when a spike wound resulted in an abscess on his knee. Collins missed the first two months of the 1912 season, during which time the Red Sox christened their new stadium, Fenway Park. Ray did not start a game until June 7, nor win one until June 22, but from that point on he was nearly invincible.

A half-century later, Ray’s fondest memory of that season was pitching the first-place Red Sox to two victories in three days over the second-place Athletics at Philadelphia’s Shibe Park. When he defeated the A’s 7-2 on July 3, the headline in the next day’s paper, over Ray’s photograph, read, “SURPRISED ATHLETICS, RED SOX AND PROBABLY HIMSELF.” Then on July 5 he surprised the A’s again, 5-3. Collins finished fifth in the American League in shutouts in 1912, but all four of them came in the second half of the season. By October his record stood at 13-8 and his ERA at 2.53, fifth-best in the American League. The team’s only left-hander, Collins was considered the second best pitcher on the staff behind Smoky Joe Wood (34-5) as the Red Sox walked away with the American League pennant.

Ray started Game Two of the World Series against New York Giants ace Christy Mathewson and led 4-2 after seven innings. Then in the eighth Collins was pulled with only one out after the Giants rallied for three runs. The game was called on account of darkness after 11 innings with the score tied 6-6 (which is why the Series went eight games). The Red Sox led the Series three games to one by the time it was Collins’s turn to pitch again in Game Six, but player-manager Jake Stahl surprised everyone by starting fireballer Buck O’Brien. O’Brien was no slouch, coming off a 20-13 season, but the Giants shelled him for five runs in the first inning. Collins took over in the second and pitched shutout ball for seven innings, but the Red Sox lost 5-2. “Things might have been a little different had Collins been sent in from the first,” Stahl admitted.

Game Six turned out to be Ray’s last appearance in a World Series, and though he ended up with no decisions, he did not walk a single batter in 14⅓ innings – quite possibly a World Series record. When a newspaperman pointed that out to him decades later, Ray responded, “Maybe I made them too good.”

Collins had his best season yet in 1913, finishing at 19-8, his .714 winning percentage the second-highest in the AL. A highlight was his performance on July 9, when he pitched a four-hitter and hit a home run in a 9-0 drubbing of the St. Louis Browns. Another characteristic outing was July 26 against the Chicago White Sox, when Collins pitched a five-hitter and hit a bases-loaded triple to give Boston a 4-1 victory. “This was simply keeping up the remarkable work that he has been doing this season, no one in the business showing better form,” was one Boston reporter’s comment.

On August 29 Collins pitched scoreless ball for 11 innings to defeat Walter Johnson, who entered with a 14-game winning streak. It was one of three times that Ray went head-to-head against the Big Train in 1913; each game was decided by a score of 1-0, with the Vermonter winning two of them.

During the 1913 season Collins became involved in the Base Ball Players’ Fraternity, an organization founded by Dave Fultz, a lawyer who had played seven years in the big leagues, 1898-1905, leading the AL in runs scored in 1903. A presage of his future leadership ability, Collins served as player representative for the Red Sox; later he was chosen as vice president for the American League and admitted to the BBPF’s board of directors and advisory board.

Coming off a fine season in 1913, Ray Collins expected his $3,600 salary to increase substantially for the 1914 season, and was sorely disappointed when the contract the Red Sox sent out on January 16 called for only $4,500. On January 23 he returned it unsigned to new Red Sox owner Joseph Lannin, prompting this response:

We have no intention of considering an increase in your case as the amount named in your contract is a very liberal one…. We have the signed contracts of most of the regular men and there is now only yours and one or two others of any importance that have not been received. We expect them, however, within a day or two. I thought you would like to know this as our prospects are very good for the coming season, with the team intact and with the addition of some promising youngsters.

In a typical year Collins would have had no choice but to accept Lannin’s terms, but 1914 was no typical year. That winter the Federal League was waging its war for baseball supremacy; players had options for the first time in years. Perhaps recognizing this, player-manager Bill Carrigan wrote the following note to Ray on February 14, enclosing another copy of the contract:

You can rest easy that you will stick with me as long as I stay with this club so don’t let anything trouble you and I will see that you get home when your wife needs you. I’ll do anything in my power to make you feel right, Ray, and hope that you will feel alright about this contract.

Ray phoned Carrigan and told him $4,500 was not enough, but that he would sign for $5,000. On February 16 Lannin wrote to Collins: “Enclosed please find contract calling for $5000.00 for the season of 1914, as per your understanding with Bill.”

On February 17, 1914, about the time he received Lannin’s letter, Collins also received a Western Union telegram from Youngstown, Ohio:

I had [Earl] Mosely [a former Red Sox teammate] wire you in regard to Federal League don’t sign or accept terms with Boston can go you more than they will pay you big money in sight three year contract money sure regardless of injury if you come here at my expense will wire you hundred before you leave answer my expense.

– Jack McAleese

McAleese, a former major leaguer, was working as a sort of bounty hunter for the Federal League, and his telegram obviously caught Ray in a receptive mood. The Vermonter sent the $5,000 contract back to Boston and raised his demand to $5,400, causing this response from Lannin:

I want to acknowledge receipt of your letter, and was very much surprised at the contents. Mr. Carrigan stated to Mr. John I. Taylor that you agreed to sign for the amount mentioned in the last contract we sent you, namely, $5000. I just talked with Mr. Carrigan on the phone, and he verified that statement to me.

We have accepted your terms, and we consider that a contract, and binding, and expect you to report at Hot Springs, as per instructions.

Collins did report to Hot Springs, but when he arrived at the Eastman Hotel he found his teammates up in arms. “They seemed to be money mad and claimed that their contracts were no good and that nothing could stop seven or eight from jumping at the Federal League money,” reported a Boston newspaper.

Most anxious to jump were pitcher Dutch Leonard and second baseman Steve Yerkes, but Federal League president James Gilmore sent the following telegram to McAleese, staying at the Arlington Hotel in Hot Springs under an assumed name: “Never mind the others; get Ray Collins by all means.” Newspapers reported that the Federal League had offered Collins a three-year contract at $5,000 per year, with a signing bonus of $7,500, and that he was slated to pitch for the Brooklyn Tip-Tops.

Ray sought advice from his older sister Genevieve’s husband, Dr. Frank Finney, a physician who lived in Burke, New York:

Since wrote letter to you Boston accepted terms of mine they once turned down. I didn’t write them between time. Does that constitute contract? Lannin comes Tuesday. Would you threaten to quit should Lannin refuse to give Federals’ terms? Wire.

Finney wired back on March 10: “You have made no contract, make Lannin meet Federal terms or satisfy you.” The next day he wired again: “No harm to Lillian, Genevieve talked with mother, all favor Feds.”

That same day Lannin arrived at Hot Springs, issuing a proclamation that Collins had 24 hours to sign with Boston or leave the team. “As late as 4 o’clock this afternoon Collins was called to the long-distance telephone and talked with President Gilmore of the Federal League, who is at Shreveport, La.,” one Boston paper reported. But Ray met with Lannin and Carrigan for an hour before dinner, and when they emerged they announced that Ray had signed a two-year contract.

That night, according to the Boston American, Ray walked around the lobby of the Eastman Hotel “as happy as a schoolboy starting a holiday.” He issued the following statement:

I am happy now that I have signed to play for the Red Sox for the next two years. I like Boston and its people and wouldn’t like to play in any other city, although I would probably have joined the Federal League if I had not signed with the Red Sox.

I will receive a much bigger salary with the Red Sox this year than I got in 1913. Just what my salary for the next two years will be I prefer to keep between Mr. Lannin and myself.

Though he refused to disclose exact terms, one Boston paper was probably correct in reporting that the contract called for $5,400 per year.

Ray’s signing was a tough blow for the Federal League. “Collins is nothing if not deliberate and shrewd,” reported one newspaper. “When the Sox saw him turn down a remarkably tempting offer from the Feds, involving the placing in his hand of a big bunch of advance coin, they suddenly lost confidence in the validity of the Feds.”

With the illness of Smoky Joe Wood, the Red Sox expected Ray Collins to step up and become the ace of their pitching staff in 1914, and that is exactly what he did. His six shutouts ranked fourth in the American League that season, and he was one of only three AL pitchers to reach the 20-win plateau. He picked up his 19th and 20th victories on September 22, 1914, by pitching complete games in both ends of a doubleheader at Detroit’s Navin Field. Collins won the first game, 5-3, and the nightcap, 5-0.

It’s no surprise that Ray’s incredible feat came against the Tigers; he seemed to own Ty Cobb, Detroit’s temperamental superstar. He once walked a batter intentionally to pitch to Cobb, and the tactic worked when Ty grounded weakly back to the mound. The Georgia Peach once said that Collins gave him as much trouble as any pitcher he ever faced. He attributed his difficulty to Ray’s peculiar windup, which caused hitters to “swing at his motion.”

Nonetheless, Collins and Cobb were friendly, and during one road trip to Detroit Ray and Larry Gardner were invited to Cobb’s home for dinner. “We went and had a nice time,” Ray remembered. The psychopathic Southerner had a genuine affection for the two educated Vermonters, whom he considered his social equals. In a rambling letter dated September 17, 1958, he wrote the following to Gardner:

Nothing would please me more than to have a few days with you and your friends in your home town amongst those real people up there that I know of and their history so well, you being such a true representative. I should tell you now though you must have for years known it so well that I liked you, also Ray, also your kind no matter where they lived. We were reared properly.

In 1915, because the Boston Red Sox were in the enviable position of having too many good pitchers, Collins was relegated to the bullpen. As early as June, newspapers began speculating that he was soon to retire; one even printed a false rumor that he had purchased a hotel in Rutland. When he pitched a two-hitter to beat Cleveland on July 14, the Red Sox players reportedly were pleased to see Ray return to his old form, but the performance turned out to be an aberration. Starting only nine games, the fewest since his rookie year, Ray finished at 4-7 with an abysmal 4.30 ERA.

What caused the sudden downturn in Ray Collins’s career? The newspapers make no mention of injury. Perhaps it was just a matter of the Red Sox having better (and younger) pitchers: Rube Foster (20-8), Ernie Shore (19-8), Dutch Leonard (14-7), and a 22-year-old lefty named Babe Ruth (18-6) made up the best rotation in baseball. (Incidentally, as an educated man of strong morals, Collins did not care for Ruth’s antics: “Ruth would drink to excess, party all night, get no sleep and arrive late for games,” Ray Jr. remembered his father telling him. Still, Ray Sr. was amazed by how well Ruth could play under those circumstances.)

Collins did not pitch a single inning in the 1915 World Series as Boston defeated the Philadelphia Phillies four games to one. After the season the Red Sox expected him to take a cut in pay to $3,500. Rather than suffer that humiliation, on January 3, 1916, Collins announced his retirement from professional baseball, stating simply that he was “discouraged by his failure to show old-time form.” He was only 29 years old.

After announcing his retirement Ray Collins was offered a position at a New York bank. With his college and baseball contacts, economics degree, and keen intellect, the job appeared to suit him well. Instead he chose to return to his family’s Colchester farm – “the worst move he ever made,” according to son Ray Jr., who was physician.

Located, ironically, just north of Poor Farm Road, the Collins Farm was hilly with marshy meadows better suited to growing rush-like swale grass than hay or corn. Because he didn’t own a tractor at first, Ray farmed in sweat-intensive, 19th-century fashion, walking behind a horse-drawn plow. For a long time the farmhouse lacked indoor plumbing; it had an outhouse and the family used the Sears catalogue as toilet paper. Lillian was not used to that sort of lifestyle, but she endured it without complaint. Nor did she raise a fuss when Ray’s mother moved back to the farm to live with the family for the next 22 years.

For years the Collinses lived without an automobile, and some still remember Ray’s forays into town on a horse-drawn wagon or sleigh: 95-year-old Walter Munson (grandson of Warren Munson, second-in-command of the Colchester Company that helped repel Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg) remembered playing “rounders” in Colchester Village with a sawdust-filled ball when Collins, on his way to the creamery, pulled a brand-new American League baseball from his overalls and tossed it to the boys.

Not every minute was a struggle. On hot summer nights Ray took his children to Nourses Beach to go swimming. On Sundays the family went to Colchester’s United Church, then picnicked in the afternoon in upstate New York or at Lake Willoughby. They participated in community silo fillings, the men from local farms banding together to help one another fill their silos with corn, followed by a common supper in the barn-raising tradition. Sometimes Ray took his sons to University of Vermont basketball games, always arriving late after the evening milking. They stood in the back of the crowded gym until someone invariably recognized Ray and ushered them to courtside seats.

By the early 1920s the knack for pitching that had left Ray in 1915 started to come back. Larry Mayforth, a former Vermont catcher then working as athletic director at the college, used to come out to the farm a couple of nights each week. After supper Ray went out front of the farmhouse and pitched to him until dark. On weekends they drove up to the Montreal suburbs, where they received $100 per game to form a battery. Ray also pitched occasionally for local town teams and in university alumni games. Sometimes the competition was even tougher.

One such occasion was July 4, 1922, when 35-year-old Ray Collins took the mound at Centennial Field against the Brooklyn Royal Giants, a black team considered one of the finest of the era. Locked up in a pitchers’ duel with Jesse Hubbard, Ray held the Giants scoreless for 12 innings and did not walk a single batter, but in the 13th he finally gave up three runs. “Collins showed the fans that he has not lost the pitching arm, and the head to go with it, which made him at one time one of the most famous twirlers in the major leagues,” the Free Press wrote. After the game, several of the Royal Giants were boarding their bus when they saw Collins in the Centennial Field parking lot. Unaware that the man who had just pitched so effectively was a former major leaguer, they approached him and asked, “Man, where did you come from?”

Several local legends developed about the ex-Red Sox star. Colchester resident Harley Monta claimed that Collins would go into his barn on rainy days and pitch baseballs through a small hole in the wall. Eben Wolcott said he heard that Collins could stand at one end of Sunderland Hollow and throw a baseball to the other. Stories like that are flattering but untrue, said Ray Jr. But he did remember one true incident that occurred at the Champlain Valley Fair in 1924. In a cruel forerunner of the dunking stool, a midway booth advertised “Hit the Nigger, Win a Cigar.” An African-American man with his head stuck through a hole in the wall waited for someone to throw a medium-soft ball at his head. The crowd urged the former major leaguer with the famous control to take his shot, but Ray refused. Then a man holding real, hard baseballs prepared to throw at the African-American. Collins became enraged. He grabbed the man’s shirt with both hands, lifted him off the ground, looked him in the eye and said, “You leave him alone!”

After a couple of seasons as a part-time assistant, Collins took over as Vermont’s head baseball coach on January 19, 1925. Following a successful Southern swing, highlighted by a meeting with President Coolidge at the White House, the Green and Gold enjoyed a memorable season. Road victories over Syracuse and Colgate caused a bonfire celebration on campus for the first time in years, and on Decoration Day more than 6,000 people showed up at Centennial Field for a game against Dartmouth. At the age of 38, Collins appeared to have finally found a position that suited him. But the coaching position did not pay enough to make up for his time away from the farm, so after the 1926 season he gave up the job.

The harder Ray threw himself into farming, it seemed, the more his luck turned against him. He used some of the money he had earned in baseball to plant an apple orchard, but the trees failed to take. In 1927 a half-dozen of his cows tested positive for tuberculosis in the state’s mandatory testing program; only after Ray took the cows to St. Albans and had them butchered did he learn that the test results were false positives. Then on October 22, 1929, a spark from a blower blade ignited dry grass and Ray’s barn burned to the ground. The barn had been equipped with state-of-the-art milking machines and its loss was estimated at $15,000. Unfortunately, the fire occurred before Ray had a chance to buy sufficient insurance. He was forced to cash in his life insurance to build its replacement.

Ray Jr. remembered his father lying down on the couch after dinner; with a long career in medicine behind him, he could only guess at the pain his father silently endured. The stress and hard work gradually wore down the man who twice pitched and won both ends of a doubleheader. During the winter of 1929-30 Ray came down with a severe strep infection. His physicians identified the germ under their microscopes but couldn’t kill it because antibiotics hadn’t been invented. They told Ray that either his immune system would kill the germ or it would kill him. Months of weakness and delirium later, Ray won.

For more than two decades the Collins family managed to scrape by. To make ends meet, Ray and Lillian took in travelers in a precursor of today’s bed and breakfasts, serving meals and talking baseball with their guests. They also supplemented their income by operating a sugarbush, wresting sap from a stand of sugar maples a mile north of the farmhouse. Ray lugged the sap buckets, a hired man boiled the sap and Lillian made and sold a variety of maple products. Eventually the Collinses won an award from the Vermont Maple Sugar Industry.

During World War II Ray chaired the town draft board and the War Bond drive. Though he probably could have secured an agricultural exemption for one of his sons, both went into harm’s way, serving with distinction and then returning to successful professional careers. Ray Sr. couldn’t carry a rifle, but he could drive a tractor – barely, due to severe arthritis in his hip from years of strenuous labor, but well enough, especially since all the young men were gone – so he hayed and plowed his neighbors’ fields, often until midnight. What drove him to sit his nearly-crippled body onto a tractor night after night, after the sun had set? Money and neighborliness, to some degree, but one can’t help but imagine that he also felt a sense of obligation to the hundreds of young men his draft board sent into the armed forces. Ray Collins, Home Front Warrior, was quietly doing his bit, and then some.

Ray Jr. remembered his father lamenting bitterly about being “peons” and living like poor people. Almost all the clothing the family wore, like Ray himself, had seen better days. Yet neighbors had no idea that Ray Collins was struggling financially. To them he was a pillar in the community. His leadership credentials were impeccable: college-educated, well-traveled, well-connected in several levels of society, a star athlete, physically imposing. From 1922, when Winooski split off from Colchester, until the 1960s, when the IBM influx to the area occurred, an oligarchy of civic-minded Republican farmers represented Colchester in the state Legislature. Ray took his turn in the Legislature from 1943 to 1946, serving on the agriculture committee and as chairman of the highway traffic committee. Looking for better prices for his milk, he co-founded the Burlington milk cooperative creamery that later became H.P. Hood and served as chairman of the county agricultural stabilization board for many years.

In 1953 Ray was named Colchester’s first zoning administrator, which required lots of measuring property. Ray and Lillian were a team; he would get out of the car and hold up one end of the tape measure, while Lillian did the walking with the other end. He also served on the school and cemetery boards. For many years he was moderator of town meetings, and he was always the foreman during his frequent jury duty. Longtime Burlington attorney Joe Wool told Ray Jr. that he loved seeing Ray Sr. as foreman because he knew everything would be done right.

Finally the arthritis got so bad that Ray could no longer operate the family farm, so around 1960 he sold it to Ray Jr. By the time of Fenway Park’s 50th anniversary in 1962, Ray Collins needed two canes just to walk. But he had missed Fenway’s 1912 opening due to a knee injury, and this time he was intent on attending. “My legs aren’t what they used to be,” he told the Boston Globe weeks before the big day, “so I’ve been out to the airport finding out how I can climb the staircase to get into the plane. I’ve been kind of training for my trip to Boston and getting accustomed to going up the staircase is part of it.” On Saturday, April 21, 1962, Collins was one of nine members of the 1912 team to make it back for the celebration (the others were Larry Gardner, Bill Carrigan, Joe Wood, Harry Hooper, Duffy Lewis, Hugh Bedient, Steve Yerkes, and Olaf Henriksen). They saw Boston’s Don Schwall defeat the Detroit Tigers, 4-3, despite home runs by Norm Cash and Al Kaline.

Collins was an active alumnus of the University of Vermont. During the 1950s he served on UVM’s board of trustees, presiding over the school’s transition from private to public university. Every year during reunions Ray hosted a Sunday brunch for the Class of ’09, and 10 or so classmates made their way out to the farm to feast on fried eggs, ham, pancakes, and Ray’s famous maple syrup. It was during one of those breakfasts in 1969 that he suffered a minor stroke. His condition gradually worsened until he died at Fanny Allen Hospital at 4 p.m. on January 9, 1970. He was buried in the Village Cemetery in Colchester.

Respect for athletic success goes only so far, and many stars squander it. Ray Collins used it as capital to serve his town, county, and alma mater. Maybe returning to Colchester and taking over the family farm wasn’t such a bad move after all.

Sources

A version of this biography originally appeared in Green Mountain Boys of Summer: Vermonters in the Major Leagues 1882-1993, edited by Tom Simon (New England Press, 2000).

In researching this article, the author made use of the subject’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, the Tom Shea Collection, the archives at the University of Vermont, and several local newspapers. In addition, the author wishes to thank Guy Page for his research assistance.

Full Name

Ray Williston Collins

Born

February 11, 1887 at Colchester, VT (USA)

Died

January 9, 1970 at Colchester, VT (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.