May 18, 1901: In first Army vs. Navy baseball game, Cadets get best of Midshipmen in Annapolis

Baseball folklore has it that Abner Doubleday “chased the cows out of Elihu Phinney’s cow pasture on an afternoon in 1839”1 and thus was inspired to invent the game of baseball. While home on leave from the United States Military Academy, as the story goes, Cadet Doubleday (Class of 1842) drew up the rules and designed a playing field, the baseball diamond, “which blazed the trail to the exciting game which has become America’s national pastime.”2

Organized baseball at West Point took shape in 1863, when a group of Cadets “applied for permission to procure the necessary equipment and play a game of baseball.”3 Their request was approved and by 1867, the regulations were published for members of the Corps of Cadets to play baseball. The sport provided exercise for the Cadets and “much amusement for the good citizens of Highland Falls.”4

The game quickly gained many followers and by the 1890s several Cadets were fielding a team to compete against other colleges and universities. The sport gained popularity, opening “a new field for the expenditure of cadet energy.”5

Ten years later, during the winter of 1900-1901, leaders at West Point and Annapolis arranged to play a series of baseball games between the two academies. Navy had fielded its first intercollegiate team in 1894.6 The first Army-Navy baseball game was scheduled for the spring of 1901, with the Army Cadets traveling to Annapolis, Maryland, to play the Navy Midshipmen.7

The Cadets honed their baseball skills with professional assistance. In his annual briefing to the president of the Army Athletic Association, First Lieutenant Leon B. Kromer, the Army’s officer representative for baseball in 1901, recounted the connection.8 He wrote, “Mr. George Davis, Manager and Captain of the New York National League Team, was engaged to come up on Saturdays during February and March to coach the candidates in batting. He came and his work was most successful; upon his advice Mr. Charles Irvine was secured to stay with the team for the month preceding the Navy game.”9

Davis, a future Hall of Fame inductee, had agreed with Lieutenant Kromer to “coach our baseball nine for a consideration of $25.00 and expenses.”10 In 1901 Davis was a star on the National League’s New York Giants and a teammate of Sammy Strang, a future Army baseball coach.11 The motion to hire Davis was moved, seconded, and carried by the Army Athletic Council. Irvine, who handled full-time coaching duties while Davis was with the Giants, proved himself to be a “most capable coach and to him is due in great measure the success of the team.”12 He had played professional baseball in Kansas City (of the Western League) and Providence (of the Eastern League) and had also gained much experience as a coach “of various college teams throughout the states.”13

The game took place on Saturday, May 18, 1901. According to US Military Academy records, “the baseball squad of 21 cadets, the coach, and an attendant left West Point, under the charge of Lieut. Leon B. Kromer, 10th Cavalry, at 1:18 P.M., Friday.”14 Traveling by train, the group spent the night in Baltimore, arriving in Annapolis Saturday morning. At the train station, the Cadets were met by both the coach and captain (Edward Hamner) of the Midshipmen team. Each team had 15 minutes on the field for warm-ups. The game started promptly at 2:30 P.M. and lasted for 90 minutes.

As was tradition in those days, the home team batted first. The Navy squad also scored first, plating a run in the top of the third inning off pitcher Ephraim Graham. Midshipman Adolphus Staton reached on a walk, stole second, and continued to third on Army catcher Horatio Hackett’s wild throw. One out later, Staton scored when David Weaver singled to left field.

Army came right back in the bottom of the third. Sherburne Whipple led off the inning and was hit by a pitch from the Navy hurler, Webb Raudenbush. Graham sacrificed Whipple to second. Edward Zell was hit in the face by Raudenbush, the second hit batsman of the inning. Frank Phipps, a plebe,15 ran for Zell.16

Douglas MacArthur, a second-year Cadet who had attended a military academy in Texas before his West Point appointment, drew a base on balls, which loaded the bases with one out. James Hobson flied out to deep right field, and Whipple tagged up and scored.17 Phipps and MacArthur also moved up on the fly ball; when Staton’s throw from right sailed over catcher Weaver’s head, Phipps scored on the error, with MacArthur moving to third.18

John Herr then singled over second base, driving in MacArthur. Army had scored three runs on one hit, one walk, two hit batters, and a Navy error.

In the bottom of the sixth, Army struck again. With one out, Stephen Abbot and Hackett had back-to-back singles. Vaughn Cooper hit a grounder to short, but Harold Childs fumbled the play and Abbot scored.

The West Pointers led 4-1 going into the ninth inning, with Graham still on the mound. Navy rallied and “amidst great excitement they scored two runs.”19 Staton again started the rally with a base on balls. James Reed forced Staton at second, but Weaver followed with an RBI double.

After Childs flied out, Byron Long singled over second, bringing Weaver around to score with the second run of the inning. “But that was all they could make; and their corps put a fitting climax to the occasion by singing ‘The Army and Navy forever, Three cheers for the Red, White, and Blue.’”20 The Army Nine triumphed by a close score of 4 to 3.

The umpire for the contest came from the National League, Charles “Pop” Snyder. Abbot and Hackett paced the Cadets’ attack, each having a 2-for-4 performance. Two double plays were turned in the game, one by each team. The Army players had five stolen bases, although three of the steals appear to have been credited to the runners who advanced on Hobson’s fly in the third inning.

The “Annual Report of Army Officers Athletic Association” reported that “Graham, the Army pitcher, is especially to be commended for his nerve and coolness under the trying disadvantages of a strange diamond and an adverse audience.”21 Graham yielded 11 hits, walked five Midshipmen, hit another two batters, and threw a wild pitch, but stranded 11 runners on base.22 The Cadets, by contrast, made the most of their seven hits, two walks, and two hit batsmen against Raudenbush.

Once back in New York, Lieutenant Kromer recommended that “silver baseballs appropriately inscribed be given to those Cadets who have represented the Academy in a game of baseball with the Cadets from the Naval Academy.”23

A new rivalry had been begun. Army and Navy agreed to play baseball every spring, alternating as hosts. In his annual report, Lieutenant Kromer wrote, “The Naval officers and cadets were ideal hosts. The cordial and sportsmanlike spirit which was manifested by all during the entire visit could but impress any witness of it that such meetings between the two services are of great mutual benefit.”24 According to the Lucky Bag, a Naval Academy publication, “The defeat by West Point was no criterion of the merits of the two teams, the score itself showing the fierceness of the contest.”25

The 1901 season ended with Army winning six, losing two, and having one tie in its nine-game schedule. Navy ended the season with a record of four wins and three losses. (There were two rainouts.)

Two future national heroes played in this game. Douglas MacArthur (USMA Class of 1903), who later earned the Medal of Honor and reached the rank of general of the Army in World War II, started in left field for Army. For the home team, right fielder Adolphus Staton (USNA Class of 1902) was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions at Vera Cruz in April 1914 and later rose to the rank of rear admiral.26

Acknowledgments

This article was fact-checked by Kevin Larkin and copy-edited by Len Levin. Thanks to Games Project Committee Chair John Fredland for information on courtesy runners and the sacrifice fly rule. (See endnotes 15 and 16.)

Sources

In addition to the sources mentioned in the Notes, the author obtained play-by-play and an official box score from “Annual Report of Army Officers Athletic Association for the Year 1901,” a document from a file labeled “Army Baseball,” located in the Archives of the United States Military Academy Library.

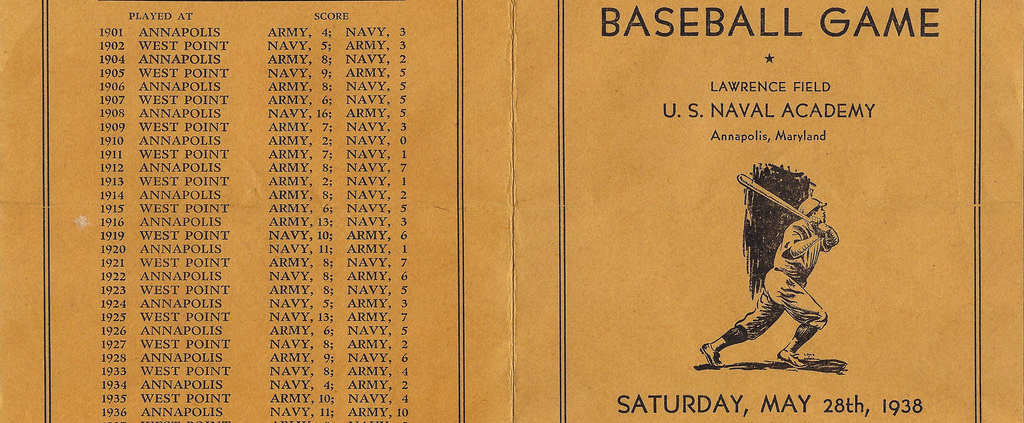

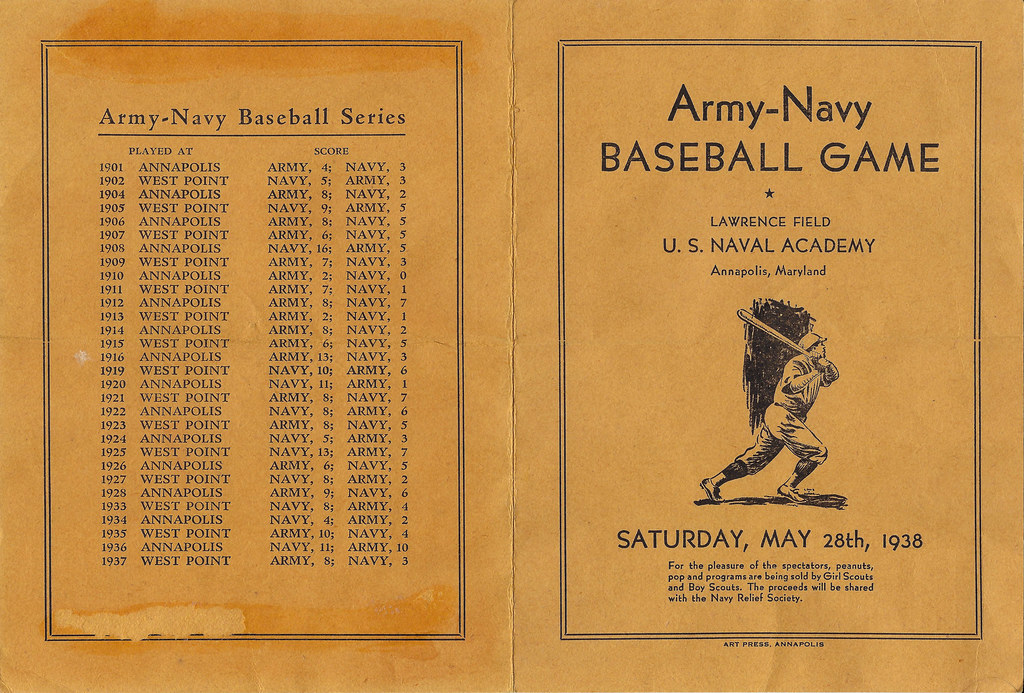

Photo credit

Army-Navy scorecard courtesy of M. Shawn Hennessy / Chevrons and Diamonds Collection.

Notes

1 The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum 1997 Yearbook (Cooperstown, New York: National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Inc., 1997).

2 A Century of Baseball (Cooperstown, New York: The Freeman’s Journal Company, 1940).

3 Lieutenant E.E. Farnsworth Jr., “Fifty Years of West Point Baseball,” from Army Navy Baseball and Track, a publication of The Pointer of the United States Military Academy, May 27, 1939.

4 Farnsworth. Highland Falls is located just outside the gates of West Point.

5 Farnsworth.

6 Navy Baseball 2022 Media Guide, found online at https://navysports.com/documents/2022/2/18/2022_Baseball_Guide_FULL.pdf. Accessed February 2022.

7 Intercollegiate competition between the two service academies dated to 1890 and the first Army-Navy football game.

8 In 1901 Kromer was also the coach of Army’s football team. He later rose to the rank of major general in the Army.

9 “Annual Report of Army Officers Athletic Association for the Year 1901.”

10 “Proceedings of the Army Athletic Council,” January 22, 1901.

11 Davis and Strang were the two switch-hitters on the 1901 New York Giants team.

12 “Annual Report of Army Officers Athletic Association for the Year 1901.”

13 “Baseball,” The News of the Highlands, May 11, 1901: 2.

14 “Annual Report of Army Officers Athletic Association for the Year 1901.”

15 A plebe is a first-year student at the academy.

16 The official box score gives credit to Zell for stealing a base and scoring a run in the third inning, even though the play-by-play account lists Phipps as a pinch-runner for Zell after he was hit in the face. Zell reentered the game in the top of the fourth inning and stayed in for the remainder of the game, making a beautiful catch of a Childs line drive in the fifth and singling to lead off the Army half of the seventh. In fact, Phipps is not even listed in the official box score. For more information on this, see Vince Johnson, “A Courtesy Runner for Lou Boudreau,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 23, 1949: 15, for a background on courtesy runners.

17 See John Schwartz, “The Sacrifice Fly,” 1981 SABR Baseball Research Journal, https://sabr.org/journal/article/the-sacrifice-fly/. Accessed February 2022.

18 The official scorer awarded all three runners stolen bases on the play.

19 “Annual Report of Army Officers Athletic Association for the Year 1901.”

20 “Proceedings of the Army Athletic Council.”

21 “Annual Report of Army Officers Athletic Association for the Year 1901.”

22 The Baltimore Sun dedicated three lines to this game. See “Maryland Contests,” Baltimore Sun, May 20, 1901: 6. Their line score was Army: 4 runs, 6 hits, 4 errors; Navy: 3 runs, 7 hits, 5 errors.

23 “Annual Report of Army Officers Athletic Association for the Year 1901.”

24 “Annual Report of Army Officers Athletic Association for the Year 1901.”

25 From a file in “U.S. Naval Academy Special Collections & Archives.” The quotation was provided to the author in an email by Gary A. LaValley, archivist at USNA, 2003.

26 “U.S. Naval Academy Special Collections & Archives.” Although he did not play in the game, Frederick Vallette McNair Jr. was on the Navy team as a substitute. According to Gary A. LaValley, McNair also won the Medal of Honor at Vera Cruz in April 1914 and later rose to the rank of captain.

Additional Stats

Army 4

Navy 3

Annapolis, MD

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.