A Pitching Conundrum: Tim Keefe and Old Hoss Radbourne

This article was written by Brian Marshall

This article was published in Spring 2017 Baseball Research Journal

In the 1912 season Rube Marquard, the left-handed pitcher of the National League (NL) New York Giants, won nineteen consecutive games and it was thought at the time to be one game shy of the record. The record was thought to be twenty, set by John Perkins “Pat” Luby, a right-handed pitcher for the NL Chicago Colts in the 1890 season. About the time of Marquard’s feat, it was also reported that Jim McCormick, a right-handed pitcher for the Chicago White Stockings, had actually set the record at twenty-four consecutive wins during the 1886 season.1, 2 Confusion ensued and after some research into the respective seasons for Luby and McCormick it was found that neither of their achievements were as long as previously portrayed.3, 4

Luby’s 1890 season only amounted to seventeen consecutive wins and McCormick’s 1886 sixteen; both fell short of the eighteen consecutive game mark that had been set by Charles “Old Hoss” Radbourne of the Providence Grays in 1884.5 The plot then thickened because, for some unknown reason, by 1912 Tim Keefe’s nineteen consecutive win season of 1888 had apparently fallen through the cracks—yet today nineteen consecutive wins in a single season represents the MLB record. The record is held by both Keefe and Marquard, both Giants, although Marquard’s mark is further distinguished by the fact that it begins with the first game of the 1912 season, April 11.

The 1950 rule defining pitching wins has been used as the criterion to define the number of pitching wins for Radbourne in the 1884 season although a conundrum has become apparent.6, 7 The conundrum results from the fact that, if the 1950 rule defining pitching wins is to be applied to Radbourne’s pitching wins in the 1884 season, then it should also be applied to Keefe’s wins during his consecutive game win streak in 1888.8 The applicable portion of the 1950 ruling, which was new that season, is provided from Division 10—The Rules of Scoring, Determining Winning and Losing Pitcher as follows:

Rule 10.16. Determining the winning and losing pitcher of a game often calls for much careful consideration.

(a) Do not give the starting pitcher credit for a game won, even if the score is in his favor, unless he has pitched at least five innings when replaced.

(b) The five inning rule to determine a winning pitcher shall be in effect for all games of six or more innings. When a game is called after five innings of play the starting pitcher must have pitched at least four innings to be credited with the victory.

(c) If the starting pitcher is replaced (except in a five inning game) before he has pitched five complete innings when his team is ahead, remains ahead to win, and more than one relief pitcher is used by his team, the scorer shall credit the victory (as among all relieving pitchers) to the pitcher whom the scorer considers to have done the most effective pitching. If, in a five inning game, the starting pitcher is replaced before pitching four complete innings when his team is ahead, remains ahead to win, and more than one relief pitcher is used by his team, the scorer shall credit the victory (as among all relieving pitchers) to the pitcher whom the scorer considers to have done the most effective pitching.

(d) Regardless of how many innings the first pitcher has pitched, he shall be charged with the loss of the game if he is replaced when his team is behind in the score, and his team thereafter fails to either tie the score or gain the lead.9

The 1950 rule book not only instituted the new ruling regarding the definition of a winning and losing pitcher, it also exhibited a brand new format of ten “divisions,” as they were called at the time. The 1949 rule book had exhibited the rule format that had been in vogue dating back to the nineteenth century.10 But for the following season, the rule book was revised and amended—or to use the rule book term, the rules were “recodified.”

THE PITCHER PERFORMANCE COMPARISON

In order to discuss the conundrum properly, it is useful to compare the 1888 Keefe streak of nineteen with the 1884 Radbourne streak of eighteen. The biggest baseball story in 1884 wasn’t the number of consecutive wins by the Providence Grays or that Charlie Sweeney or Hugh Daily struck out nineteen in a single game; it was the overall season performance of Charles “Old Hoss” Radbourne.11 His season was nothing short of incredible, leading the National League in virtually every significant pitching category including wins, strikeouts, ERA, innings pitched, games started, and complete games. There is also one category they didn’t have a counting statistic for and that was dogged determination, or “guts,” if you will. The funny thing is that Radbourne’s magical season almost didn’t happen because early on Providence management was leaning toward Charlie Sweeney. Radbourne would have played second fiddle to Sweeney, except Sweeney threw it all away and left the team. Radbourne stepped up and the rest, as they say, is history.

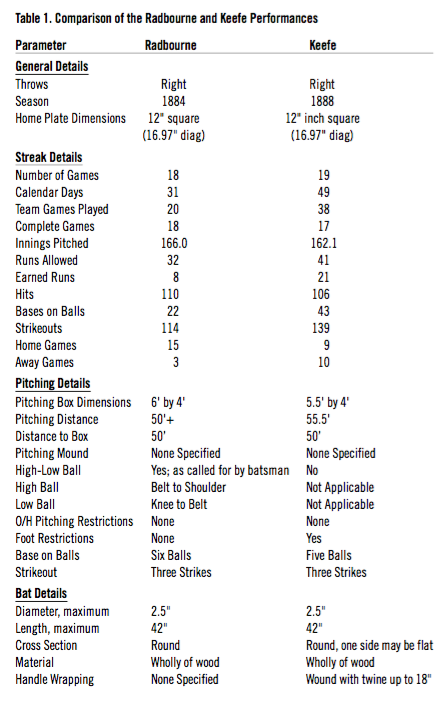

Table 1. Comparison of the Radbourn and Keefe Performances

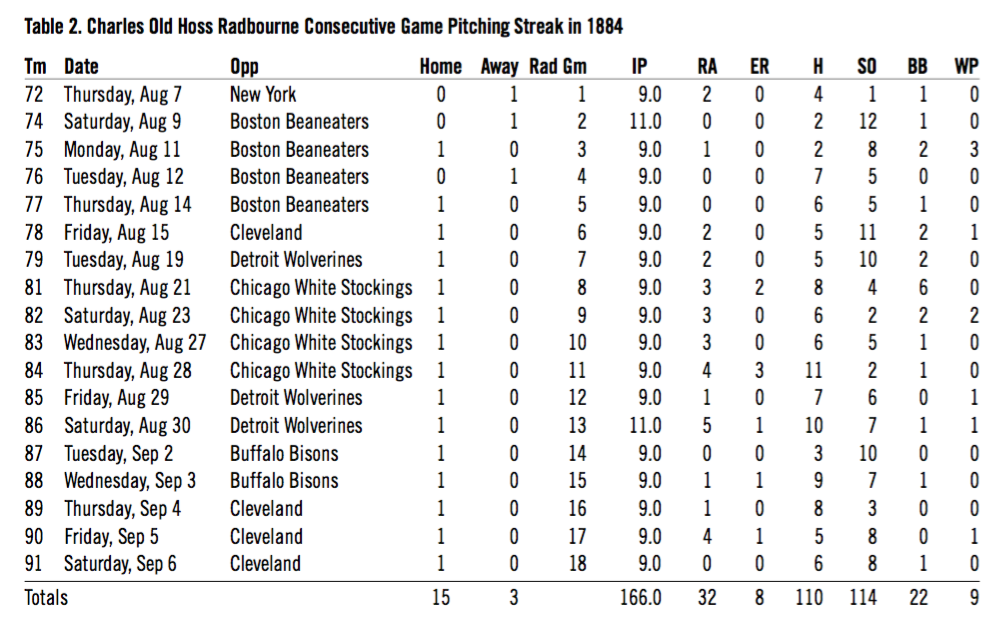

Radbourne pitched in 75 of his team’s 114 games played during the regular season, including 22 consecutive, won 18 consecutive pitching starts (see Table 1) and pitched nine complete games in 11 calendar days, winning all nine. The nine games were part of his eighteen consecutive game win streak, from August 27 through September 6, and one of the nine was an 11-inning game. In an article written by Frank Bancroft, who managed the Providence Grays in 1884, the following quotation made by Radbourne himself in 1884 appears: “I will win or pitch my right arm off.”12

Radbourne pitched in 75 of his team’s 114 games played during the regular season, including 22 consecutive, won 18 consecutive pitching starts (see Table 1) and pitched nine complete games in 11 calendar days, winning all nine. The nine games were part of his eighteen consecutive game win streak, from August 27 through September 6, and one of the nine was an 11-inning game. In an article written by Frank Bancroft, who managed the Providence Grays in 1884, the following quotation made by Radbourne himself in 1884 appears: “I will win or pitch my right arm off.”12

Radbourne effectively did pitch his right arm off in 1884. The same article also included the following quotation regarding Radbourne’s dogged determination:

Morning after morning upon arising he would be unable to raise his arm high enough to use his hair brush. Instead of quitting he stuck all the harder to his task going out to the ball park hours before the rest of the team and beginning to warm up by throwing a few feet and increasing the distance until he could finally throw the ball from the outfield to the home plate.13

The 1884 season was also important in National League history for the fact that it was the first season the rules did not define or restrict the pitching arm’s movement. The pertinent section of the 1883 rule book read as follows, from Class IV, Definitions: “Rule 27. A Fair Ball is a ball delivered by the Pitcher, while wholly within the lines of his position and facing the Batsman, with his hand passing below his shoulder, and the ball passing over the home base at the height called for by the Batsman.”14

The corresponding rule from the 1884 rule book deleted the “with his hand passing below his shoulder” and read as follows:

Rule 27. A Fair Ball is a ball delivered by the Pitcher, while wholly within the lines of his position and facing the Batsman, and the ball passing over the home base at the height called for by the Batsman.15

Lack of restrictions regarding arm movement during the pitching motion opened the door for pitchers to pitch overhand (O/H) in the National League for the first time, introducing a major change to the way the game was played. Strikeouts were becoming a bigger part of the game at that time, increasing in 1884 in the National League, and in recent years in the other two major leagues where underhand pitching remained the norm, the Union Association (UA) and American Association (AA).

The following season another rule change would again impact National League pitching, this time defining how the feet should be positioned and aimed at eliminating the “jumping tactics” of Radbourne himself.16 In 1885, the new rule read as follows, from Class IV, Definitions:

Rule 27. A Fair Ball is a ball delivered by the Pitcher while standing wholly within the lines of his position, and facing the batsman [sic], with both feet touching the ground while any one of the series of motions he is accustomed to make in delivering the ball to the bat, the ball, so delivered, to pass over the home base and at the height called for by the batsman [sic]. A violation of this rule shall be declared a “Foul Balk” by the umpire, and two Foul Balks shall entitle the batsman to take first base.17

Other changes to the rules were made between 1884 and 1888, but this is one key difference that brings attention to the pitching technique of Radbourne.18

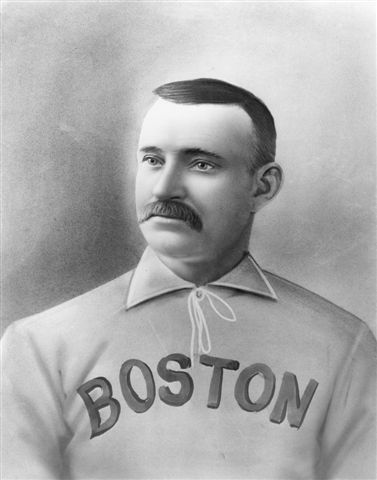

Now to Keefe. The 1888 season began slowly for him when it was reported that as of April 20, he was holding out for an increase of $500 in salary and then signed on April 27, for $1000 more than his salary in 1887, which was listed as $3000.19, 20 As a result of the hold-out Keefe did not participate in any of the first nine games of the season and pitched his first game for New York on May 1, 1888, a 6–1 victory over Boston—the first of a league-leading 35 wins that season. But the nineteen-game win streak was yet to come.

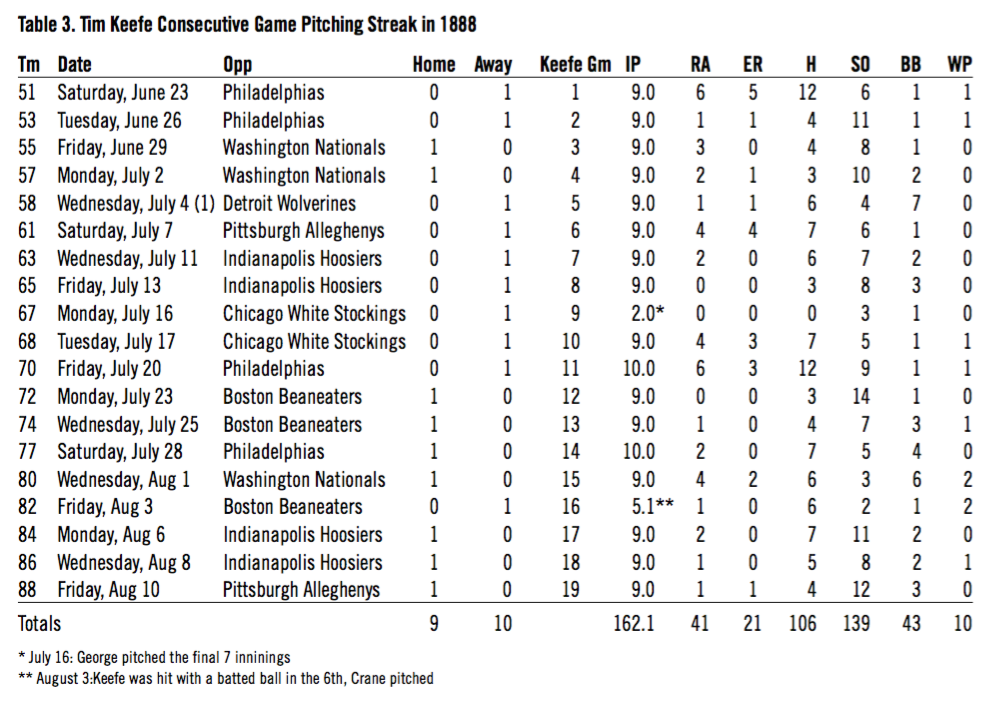

The Keefe streak took place over 49 calendar days, from June 23, to August 10, 1888. The Radbourne streak had spanned 31 calendar days, August 7 through September 6, 1884. Table 1 compares the two streaks. During the Keefe streak the New York Giants played 38 games while the Providence Grays played only 20 during the Radbourne streak. Ed Conley pitched for Providence during the two games that Radbourne didn’t, while four other pitchers—Mickey Welch, Ed Crane, Stump Weidman, and Bill George—pitched for New York in the remaining 19 games that Keefe didn’t pitch.

Radbourne’s eighteen consecutive wins, in as many starts, were complete games, while Keefe pitched seventeen complete games in his nineteen consecutive wins in as many starts. Interestingly, in the two games Conley pitched during Providence’s twenty-game win streak, Radbourne played right field and shortstop respectively. Keefe typically wasn’t in the game unless pitching, although there was one exception during the streak: the July 16 game.

The two games that Keefe did not complete only amounted to a total of 7.1 innings pitched, which is why his total innings for his streak was 162.1 and Radbourne’s was 166. The first of the two games was on July 16, 1888—Game 9 of the nineteen-game streak. Keefe started but pitched only the first two innings before being replaced by Bill George. George pitched the remaining seven innings to finish the game, which the Giants won, 12–4, over the Chicago White Stockings. This game was interesting right from the start in that the designated umpire, Tom Loftus, did not show up and Chicago was forced to accept New York’s pitcher, Mickey Welch, as the umpire for the game.21 George started the game in right field but, in order to save Keefe for the game the following day, was summoned to the pitcher’s box to begin the third inning and Keefe finished the game in right field.22

Keefe did, in fact, pitch the following day, July 17, against the Chicago White Stockings, going nine innings in a 7–4 victory, his tenth consecutive win. It was the only time during the streak that Keefe pitched on back-to-back days. Keefe pitched in consecutive games on July 2 and 4 (the latter in the first game of two played that day) but they were not on back-to-back days.

The second of the two games Keefe did not complete was on August 3, 1888, game 16 of the nineteen-game streak. Keefe only managed to complete 5.1 innings due to being hit with a batted ball after Dick Johnston had flied to George Gore. Keefe was replaced by Ed Crane, who pitched the remaining 3.2 innings to complete the game. A Boston newspaper described the hit: “Wise batted a stinging ball that hit Keefe on the muscles of his pitching arm and the New Yorker was obliged to retire, Crane being called in to take his place.”23

Keefe’s top performance from a strikeout point of view came on July 23, 1888, when he struck out 14 (in nine innings) against the Boston Beaneaters, while Radbourne’s top strikeout performance was 12 in an 11-inning game on August 9, 1884, also against the Beaneaters. During the streak Radbourne gave up 11 hits on August 28, 1884, against the Chicago White Stockings while Keefe gave up 12 hits in two separate games—June 23 and July 20, 1888. The July 20 game, against the Philadelphia Quakers, was a 10-inning affair. A game-by-game breakdown for the Radbourne streak is shown in Table 2, and the Keefe streak in Table 3. One large disparity: 15 of the 18 games during Radbourne’s streak were at home while only nine of the 19 games were at home for Keefe.

Table 2: Old Hoss Radbourn Consecutive Game Pitching Streak in 1884

Table 3: Tim Keefe Consecutive Game Pitching Streak in 1888

The HBP (Hit by Pitch) statistics don’t appear in the tables because in the 1884 National League, a batter was not awarded first base upon being hit. Accurate numbers aren’t readily available for all years, but Keefe had developed a reputation as a beanball artist. Keefe hit five batters in a single game (the National League record at the time) on June 12, 1885, vs Boston Beaneaters.24 The following nugget from the December 1885 issue of Sporting Life provides some insight into Keefe’s practices:

KEEFE has a habit of trying how near he can pitch the ball to a batsman’s head without hitting him, and thus intimidates the man. He hits more men than all the other League pitchers combined. It was for Keefe’s sake that the rule giving a batsman a base when hit by the pitcher was adopted by the American Association when he was with the Mets, and it was for Keefe’s benefit that the New York Club secured its defeat at the recent League meeting.25

During the Keefe streak four other significant baseball-related events took place:

1) The New York Giants sported brand new uniforms well into the season that apparently Keefe selected.26, 27

2) Buck Ewing’s consecutive game streak at the catcher position.

3) The notice to the New York Giants, owned by the Metropolitan Exhibition Company, from the Central Park Board, of New York, that the fences on the Polo Grounds across One Hundred and Eleventh Street had to be removed.28

4) John Ward’s book was published.29

THE PITCHING CONUNDRUM

The thinking on August 16, 1888, was clear: Tim Keefe had won nineteen consecutive games in nineteen consecutive starts and it was stated as such (“.…Keefe had won 19 straight games.…”) in the New York Times.30 To this day Keefe’s record of nineteen straight is still the MLB standard, although it was tied by Rube Marquard in 1912. But in game nine of the nineteen-game streak, on July 16, 1888, Keefe’s pitching in only the first two innings but being awarded a win presents a conflict with the 1950 rules.

Hence, the conundrum. Are the 1950 rules even applicable to nineteenth century games? They come into play because they have been applied to the wins recorded in Radbourne’s 1884 season. The Giants were ahead 9–0 at the time Keefe left the July 16 game, and they went on to win 12–4, but based on the 1950 rules Keefe should not be credited with a win. That represents conundrum issue number one. Why was Keefe credited with a win on July 16? A publication that may shed light on the thinking of the time as it relates to the scoring is another Spalding publication: HOW TO SCORE: A Practical Textbook for Scorers of Base Ball Games, Amateur and Expert. In a section entitled “Crediting or Charging the Pitcher,” the following is stated:

.…The nearest to a set of rules on the subject that can be codified may be formulated as follows: .…If the pitcher who first works has been taken out at any stage of the game with the comparative score in favor of his opponents, should the game be eventually won by his team, credit must be to the second pitcher. Should the game be lost the first pitcher is charged with the loss.31

With regard to the “Crediting or Charging the Pitcher” section, and with particular respect to the game of July 28, 1884, when Old Hoss Radbourne went into the game, at the start of the sixth inning to replace Cyclone Miller, who had pitched five complete innings, the Philadelphia Quakers were leading, 4–3. Not a hit was made off of Radbourne and his team went on to win, 11–4. Based on the “Crediting or Charging the Pitcher” section, Radbourne should be declared the winning pitcher because that was the general school of thought at the time.

Upon further review, on that same basis it may be that Radbourne should also be credited with the win for the July 8, 1884, game with the Buffalo Bisons. The score was tied 5–5 after nine innings pitched by Charlie Sweeney, and Radbourne pitched in the tenth when Providence went ahead 6–5 and won. The July 8 game was mentioned by Sweeney when he spoke in 1897 (from San Quentin prison) and his statement lends credence to the fact that giving the win to the finishing pitcher if the team went ahead to win was the general thinking of the time. Sweeney stated, “In Buffalo I pitched my first game after my arm was hurt. The score was tied in the ninth inning, when Bancroft said to me: ‘Had you not better let Radbourne go in, Charlie; your arm is pretty sore yet?’ I said, ‘alright if he wants to.’ He went in and he won in the tenth inning.”32

The Radbourne games of July 8 and 28, 1884, represent conundrum issue number two because of their impact on Radbourne’s overall win total in the 1884 season.

To advance the “general thinking of the time” theory, consider that both the 1885 Spalding Guide and the Boston Journal newspaper credit Radbourne with 60 wins.33 So does Elwood A. Roff’s Base Ball and Base Ball Players published in 1912.34 Reviewing the 1950 rules in detail exposes the fact that Radbourne should be credited with a minimum of 60 wins for the 1884 season and not 59. The official National League pitching statistics for the 1884 season that were published in 1885 Spalding Guide and the Boston Journal newspaper both indicate the same numbers, except for the average bases on balls statistic: 74 games played (should be 75), 62 games “won” (includes the two tie games), 1.09 average runs earned (81 earned runs), 5.90 average assists on strikes (437 strikeouts), 7.09 average base hits (525 base hits) and 1.28 average bases on balls (95 bases on balls).

The fact that 60 wins—plus two tie games, which weren’t wins—were included in the 62-win number lends credence to the 60 win number for Radbourne. The official 1884 pitching statistics only list 74 games pitched, yet we know Radbourne pitched in 75 games which implies that one game was omitted, leaving room for the July 8 game to be accommodated—presuming that it is credited as a win for Radbourne. If the July 8 game is credited as a win, it would give Radbourne a total of 61 wins, 12 losses and 2 ties in 1884, totaling 75 games pitched.

SUMMARY

On the surface the Radbourne and Keefe consecutive game win streaks appear to be similar. They differ by only a single game. But upon closer examination, the performances are very different. Among the key differences:

a) number of calendar days for each streak

b) number of team games played during each streak

c) number of complete games

d) number of innings pitched

e) pitching in consecutive games on consecutive days

f) number of home games

g) high or low ball pitching requirement

h) number of called balls for a base on balls

i) foot positioning

j) size of pitching box

k) bat cross section and handle wrapping

The comparison isn’t really apples-to-apples because of these differences, and delineation in the record books should reflect this. Radbourne and Keefe pitched from pitching boxes with slightly different dimensions and, though the rules of the time did not define a pitching “mound,” that did not stop the groundskeepers from adjusting the height of the pitching box.35 Another interesting fact—this one related to the bat—was that the rules of the time did not stipulate that the bat had to be one piece as they do today, which is why a 13-piece bat was able to be used by Chicago.36

Regarding the two conundrum issues, either the general thinking of the time must be accepted, or if the 1950 rules are to be applied it should be done consistently for both pitchers’ seasons. Applying the 1950 rules would result in the Keefe nineteen-game streak being scratched. Given that Cummings’ How to Score shows there was an acceptable method for determining the winning pitcher at the time, there is little reason to apply the 1950 rules anachronistically. This researcher is in favor of accepting the general thinking of the time, which would mean Radbourne should be credited with a minimum of 60 wins—maximum of 61—for the 1884 season and Keefe’s nineteen-game record would remain.

BRIAN MARSHALL is an Electrical Engineering Technologist living in Barrie, Ontario, Canada and a longtime researcher in various fields including entomology, power electronic engineering, NFL, Canadian Football and MLB. Brian has written many articles, winning awards for two of them, and has two baseball books on the way: one on the 1927 New York Yankees and the other on the 1897 Baltimore Orioles. Brian has become a frequent contributor to the “Baseball Research Journal” and is a longtime member of the PFRA. Growing up Brian played many sports including football, rugby, hockey, baseball along with participating in power lifting and arm wrestling events, and aspired to be a professional football player but when that didn’t materialize he focused on Rugby Union and played off and on for 17 seasons in the “front row.”

Notes

1 George L. Moreland. Balldom: “The Britannica of Baseball.” New York, NY: Balldom Publishing Company, 1914. 304 pages. Reprinted in 1989 by Horton Publishing Company.

2 Francis C. Richter. Richter’s History and Records of Base Ball: The American Nation’s Chief Sport. Philadelphia, PA: Francis C. Richter, 1914.

3 Elwood A. Roff. Base Ball and Base Ball Players: A History of the National Game of America and the Important Events Connected Therewith From its Origin Down to the Present Time. Chicago, IL: E. A. Roff, 1912, 95–96.

4 An interesting comment related to the number of wins by McCormick comes from Sporting Life, Volume 23, Number 16, July 14, 1894, page 4. “LEAGUE GOSSIP; GENERAL COMMENT−Under present rules no League pitcher will ever duplicate McCormick’s famous record of nineteen [sic] consecutive victories. Nowadays just as soon as a pitcher’s chest begins to swell out over a few victories some team is sure to come along and hit it with an axe.”

5 Charles “Old Hoss” Radbourne’s last name was apparently arbitrarily spelled with and without an “e” on the end by various literature sources, newspapers, et cetera throughout the course of his baseball career. There simply wasn’t any consistency but at the time of his death Sporting Life used the Radbourne spelling. See “RADBOURNE’S RELIEF: Death Ends the Suffering of a Noted Man,” Sporting Life, Volume 28, Number 21, February 13, 1897, page 1. The Radbourne spelling is also on his gravestone, which is why this researcher elected to go with the Radbourne version.

6 Edward Achorn. Fifty-nine in ’84. New York, NY: Harper-Collins Publishers, 2010, 209.

7 Edward Achorn. “Old Hoss Radbourn: 59 or 60 Victories?” in Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the Nineteenth Century, edited by Bill Felber, 2013. Phoenix, AZ: Society for American Baseball Research, 170–71.

8 Regarding the 1950 rule on pitching wins, this discussion is confined to Radbourne and Keefe. This isn’t to say, or imply, there were not other performances that could be discussed in relation to the 1950 rule, including the Marquard streak of 1912 and others. Other performances would be best discussed in an article that deals solely with the topic of the 1950 ruling.

9 J.G. Taylor Spink, compiled by. Baseball Guide and Record Book 1950. St. Louis, MO: Charles C. Spink & Son (The Sporting News), 1950, 570, 571.

10 J.G. Taylor Spink, compiled by. Baseball Guide and Record Book 1949. St. Louis, MO: Charles C. Spink & Son (The Sporting News), 1949.

11 The 1884 season saw the Providence Grays win twenty consecutive games to tie the record set by the Chicago White Stockings set in 1880. The 1880 White Stockings went twenty-two consecutive games undefeated; they had won a game, then tied a game, then won twenty in a row for a total of 22 games undefeated.

12 Frank C. Bancroft. “Old Hoss” Radbourn.” Baseball Magazine, July 1908, 12–14.

13 Bancroft.

14 Spalding’s Base Ball Guide and Official League Book for 1883. Chicago, IL: A. G. Spalding & Bros., 1883, 74–75.

15 Spalding’s Base Ball Guide and Official League Book for 1884. Chicago, IL: A. G. Spalding & Bros., 1884, 86.

16 “BASEBALL RULES CHANGED: Yesterday’s Session Of The Delegates Of The League Clubs,” The New York Times, Friday, November 21, 1884, 2.

17 Spalding’s Base Ball Guide and Official League Book for 1885. Chicago, IL: A. G. Spalding & Bros., 1885, 112.

18 There was also another rule change, although unrelated, concerning the short right field fence of the Chicago grounds that may be of interest to readers. The fence of the Chicago grounds was only 196 feet from home plate and 131 home runs had been hit there by the Chicago players in 1884. The new rule, Rule 65 (1), defined that a ball had to be hit over the fence a minimum of 210 feet from home plate for it be declared a home run, otherwise it was to be scored as a double. See Spalding’s Base Ball Guide and Official League Book for 1885, page 120.

19 “GOSSIP OF THE GAME: Tim Keefe Wants More Salary,” The Chicago Tribune, Saturday, April 21, 1888, 7.

20 “Keefe Signs a New York Contract,” The Chicago Tribune, Saturday, April 28, 1888, 3.

21 “DALY’S THROW TO SECOND: The Ball Hits Pitcher Baldwin On The Head,” The Chicago Tribune, Tuesday, July 17, 1888, 3.

22 “NEW-YORK WINS EASILY: The Giants Defeat The Chicago Club 12 To 4,” The New York Times, Tuesday, July 17, 1888, 2.

23 From a Boston newspaper account of the game on 1888 Boxscore Microfilm at the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, NY.

24 The five batters that Keefe hit on June 12, 1885, were Joe Hornung, John Morrill, Jim Manning, Jack Burdock, and Ezra Sutton.

25 Sporting Life, Volume 6, Number 8, December 2, 1885, page 1.

26 The brand new uniforms were apparently selected by Keefe. The players were measured for the new black jersey suits, as they were called, at Spalding’s on July 14 which the team debuted on July 28, 1888. The new uniforms were described in The New York Times as follows: “As the New-Yorks marched upon the field yesterday they could hardly be recognized. The uniform of white pants and shirts and maroon stockings had been cast aside, and the men came out in a new outfit. It consisted of black shirts, knickerbockers, stockings, and caps of the same color, a white belt, and the words ‘New-York’ in white raised letters across the breast. The uniform is made of jersey cloth, and is tight-fitting.” From “NEW-YORK IN THE LEAD: The Giants Even With Detroit For First Place,” The New York Times, Sunday, July 29, 1888, 3.

27 See also “SHORT STOPS,” The New York Times, Sunday, July 29, 1888,page 3, and “League Notes,” The Chicago Tribune, Wednesday, July 18, 1888, 3.

28 The original Polo Grounds were bounded on the South by 110th Street, the North by 112th Street, the East by Fifth Avenue and on the West by Sixth (aka Lenox) Avenues, just north of Central Park. At the time One Hundred and Eleventh Street had been closed then fenced off to enclose the ball field. See “The Polo Grounds in Danger,” Sporting Life, Volume 11, Number 11, June 20, 1888, page 2 and “THE POLO GROUNDS MUST GO: An Adverse Decision Rendered by Judge Ingraham,” The New York Times, Sunday, July 15, 1888, 3.

29 John Montgomery Ward. Base-Ball: How To Become A Player: With the Origin, History, and Explanation of the Game. Philadelphia, PA: The Athletic Publishing Company, 1888. SABR reissued a reproduction of this book in paperback in 1993 under the title Ward’s Baseball Book, and again in 2014 under the original title Base-Ball: How to Become a Player.

30 “ANSON’S RECORD BREAKERS: New-York “Chicagoed” The First Time This Year,” The New York Times, Thursday, August 16, 1888, page 3.

31 J.M. Cummings. HOW TO SCORE: A Practical Textbook for Scorers of Base Ball Games, Amateur and Expert, part of the Spalding’s Athletic Library, Group 1, No. 350. New York, NY: American Sports Publishing Company, 1919, 52–53.

32 Spalding’s Base Ball Guide and Official League Book for 1885, 28–29; “THE PITCHING: The Work Accomplished by the Twenty-four Pitchers,” Boston Journal, Morning Edition, Thursday, October 16, 1884.

33 “SWEENEY SPEAKS: From His Prison Cell He Scores Frank Bancroft,” Sporting Life, Volume 28, Number 24, March 6, 1897, 11.

34 Elwood A. Roff. Base Ball and Base Ball Players. Chicago: E. A. Roff Printer and Publisher, 1912, 66.

35 “As the pitchers’ box on the Brooklyn grounds is very high….” a statement which appeared in “MURNANE’S MISSIVE,” Sporting Life, Volume 15, Number 6, May 10, 1890, 12.

36 “Secretary Brown sent Capt. Anson a new bat a few days ago, and the first thing the old man did was to take the club and Sullivan, Sunday, and Darling out to the Washington grounds, where he began practicing. The stick is made of thirteen pieces of wood and the long, slender handle is wound with twine.” From “Around the Bases,” Chicago Tribune, Thursday, September 8, 1887, 3.