1908’s Forgotten Team: The Pittsburgh Pirates

This article was written by Steve Steinberg

This article was published in Fall 2018 Baseball Research Journal

The 1908 National League race is best remembered for the “Merkle game” between the New York Giants and the Chicago Cubs, who were in a dead heat for first place at the end of the season. The clubs met to replay that tie game. The Cubs won and went on to beat the Detroit Tigers in the World Series for the second year in a row. But there was a third team in that season-long struggle, a team that, like the Giants after the replayed game, finished just a game out of first place, the Pittsburgh Pirates. Here are the final 1908 National League standings:

| Team | Wins | Losses | Pct. | GB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cubs | 99 | 55 | .643 | — |

| Giants | 98 | 56 | .636 | 1 |

| Pirates | 98 | 56 | .636 | 1 |

The Pirates’ season and place in the race has largely been forgotten — partly because New York and Chicago were larger media centers, partly because managers John McGraw of the Giants and Frank Chance of the Cubs were such dominant personalities, and partly because the fierce Giants-Cubs rivalry came together in the Merkle controversy. In her book Crazy ’08, Cait Murphy wrote, “In this triangular pennant race, Pittsburgh is clearly the short side in terms of attention. New York and Chicago, the nation’s two biggest cities, have a rivalry that goes deeper than baseball, and their fans are more passionate. Looked at strictly in baseball terms, though, Pittsburgh is no also-ran. . . . This is a good team having a very good year.”1

The Pirates’ season and place in the race has largely been forgotten — partly because New York and Chicago were larger media centers, partly because managers John McGraw of the Giants and Frank Chance of the Cubs were such dominant personalities, and partly because the fierce Giants-Cubs rivalry came together in the Merkle controversy. In her book Crazy ’08, Cait Murphy wrote, “In this triangular pennant race, Pittsburgh is clearly the short side in terms of attention. New York and Chicago, the nation’s two biggest cities, have a rivalry that goes deeper than baseball, and their fans are more passionate. Looked at strictly in baseball terms, though, Pittsburgh is no also-ran. . . . This is a good team having a very good year.”1

Both McGraw and Chance saw each other’s team as their key competitor in 1908; they were not concerned about the Pirates. Early in the season, McGraw said, “The Giants have just one team to beat, the Chicago Cubs.”2 In early August, Christy Mathewson explained why his focus and concern was on the Cubs: “Chicago, in my mind, is the one team we have to beat. I figure the Cubs stronger than the Pirates because of the experience of Frank Chance’s men and the confidence that the successes of two consecutive years have engendered.”3 While McGraw seemed to ignore the Pirates, Chance put them down. In May he said, “They [the Pirates] are pretty sure to blow before the season is half over.”4

Each of these three teams had a pitching great; all three men would be elected to the Hall of Fame. Mathewson would have perhaps his greatest season in ’08, going 37–11 with a 1.43 ERA, and the highest WAR of his career, 11.7. Mordecai Brown of the Cubs would post a 29–9 mark with a 1.47 ERA; his WAR of 9.5 was second only to his 1909 mark of 9.6. Vic Willis of the Pirates, far less known than the other two, would have a 23–11 record with a 2.07 ERA. His WAR of 4.7 lagged behind that of the other two aces and was considerably below that of his best seasons (he had four with a WAR of more than 8.0).

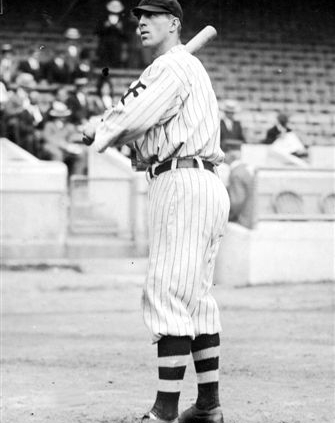

If the Pirates had the league’s third-best pitching ace, they had by far the league’s best everyday player, shortstop Honus Wagner. The 34-year-old star had an arthritic shoulder and was talking of retiring before the season began. But when Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss doubled his annual salary to $10,000, he reported to the team. He would bat .354 in 1908, with a career second-best OPS of .957. His WAR of 11.5 was his best ever, and he also had 20 more extra-base hits than his nearest competitor. Giants pitcher Hooks Wiltse, who would win 23 games in 1908, felt the Pirates were more dangerous than the Cubs. “The Pirates. Ah, there’s the dig. Pittsburgh may be a one-man team, but that one man is a ‘dilly.’”5

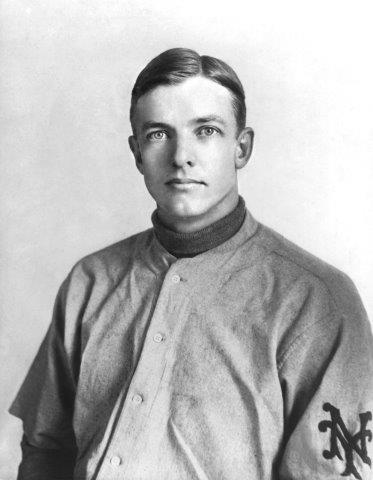

While the Cubs did not have a big hitting star in 1908, the Giants had one in outfielder Mike Donlin. While it seems surprising today, more than 100 years later, Donlin was considered not far behind Wagner in hitting ability at the time. Donlin hit .351 in 1903, only to be edged for the batting title by Wagner’s .355. Two years later, he hit .356, yet Wagner edged him again with a .363 mark (while Cy Seymour led with .377). Donlin missed most of the 1906 season with a broken leg and did not play at all in 1907, when he joined his famous wife, Mabel Hite, on the vaudeville circuit.6

His battle with Wagner in ’08 would be one of the season’s leading stories.

| June 30 | July 31 | August 31 | Final | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wagner | .314 | .331 | .340 | .354 |

| Donlin | .351 | .339 | .330 | .354 |

Donlin’s enormous popularity among New York fans in 1908, exceeding that of the beloved Mathewson, seems surprising today. A New York Evening Mail reporter wrote on August 1, “Mike Donlin, one of the best ball players who ever graced a New York uniform, and without a doubt the most popular player the city has ever had, will make his debut as an actor. . . . He wants to quit at the height of his popularity and will go out of the National League in a blaze of glory.”7 Just a few days later a New York World sportswriter wrote, “Mike Donlin’s admirers — and no man that ever wore the uniform of the Giants was more popular in this city than Turkey Donlin — claim he is handicapped by his position in right field. Otherwise no one would dispute that he is Wagner’s equal.”8

The home-road splits of the three teams in 1908 were significant:

| Home W-L | Pct | Road W-L | Pct | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cubs | 47-30 | .610 | 52-25 | .675 |

| Giants | 52-25 | .675 | 46-31 | .597 |

| Pirates | 42-35 | .545 | 56-21 | .727 |

The Giants’ home record could be explained at least in part by their intimidation of umpires, accordingly to sportswriter James Crusinberry: “On the Polo Grounds in New York, where policemen dare not tread and visiting players and umpires are in danger of their lives, victories have been comparatively easy for the Giants.”9

The Pirates had the worst home record of the three clubs, and as the season drew to a close, their player-manager, Fred Clarke, suggested the club’s support could have been better. “The fans of Pittsburg have not supported us as they might have done,” he said. “Any glory that might accrue to the city from the way we finish the season belongs to the players and not to the people. . . . The boys did not depend on the plaudits of the multitude, and they paid no attention to the smears and criticisms that were hurled at them.”10

The Pirates had the worst home record of the three clubs, and as the season drew to a close, their player-manager, Fred Clarke, suggested the club’s support could have been better. “The fans of Pittsburg have not supported us as they might have done,” he said. “Any glory that might accrue to the city from the way we finish the season belongs to the players and not to the people. . . . The boys did not depend on the plaudits of the multitude, and they paid no attention to the smears and criticisms that were hurled at them.”10

Clarke’s approach was quite different from that of McGraw in dealing with umpires. He said, “There’s nothing to be gained by paying attention to the umpires, but it may mean a big loss when men get put out of the game.”11

Wagner was a thorn against the Giants all season long. He almost singlehandedly beat them on both May 11 and June 11, by identical scores of 5–2. In the first game, the opener of a three-game series in Pittsburgh, his triple was the key blow, but not the only one. The Pittsburg Leader reporter wrote, “The performance and achievements of the big German in the opening contest against the Giants truly beggar description. He was in the main responsible for each of the five runs the locals secured and played perfectly in the field.”12 On June 11 in New York, his home run off Mathewson helped them win, 5–2. Wagner was also a force in the field. “The wonderful Teuton was everywhere, choking off sure hits and encouraging his comrades,” wrote William Kirk. “His large paws, the fingers of which seemed like tentacles of a devil fish, raked in everything that came within a mile of them. Oh, Honus, how could you do it?”13

At the end of June, the three clubs were within three games of each other:

| Team | Wins | Losses | Pct. | GB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pirates | 40 | 24 | .625 | — |

| Cubs | 37 | 23 | .617 | 1 |

| Pirates | 37 | 27 | .578 | 3 |

The most significant run that month was made by the Pirates, who had been just 15–15 on May 29.

Mordecai Brown shut out the Pirates on July 2 and again on July 4, on one day’s rest. His record that season against the other two teams was impressive: 6–3 vs. New York and 6–1 vs. Pittsburgh. Mathewson, on the other hand, had a .500 record against both clubs, and Willis went 4–3 against Chicago and 3–2 against New York. The scrappy Pirates bounced back with a dramatic 7–6 win over the Giants on July 10 on Tommy Leach’s inside-the-park home run.

“Though Mike Donlin pursued the ball with the speed of a greyhound,” wrote a New York reporter, “he could not get it to [catcher Roger] Bresnahan in time to head off the wee whaler.”14

On July 25, Wagner went 5-for-5 with four hits off Mathewson in a 7–2 Pittsburgh win at the Polo Grounds, and the New York papers saluted the mighty slugger. “Wagner’s ability to do almost anything at any time gives the Pittsburg infield a wonderful lot of confidence,” was a typical comment.15 After the game, Polo Grounds fans tried to carry the Pirate shortstop on their shoulders, but he “escaped” with the help of his teammates.

Perhaps because of his greatness and perhaps because of his modesty, Wagner had enormous fan support in New York. The New York Tribune noted, “Such mighty swatting against a pitcher of Mathewson’s caliber is seldom seen and was worth the price of admission alone.”16 Ralph Davis, who covered the Pirates for The Sporting News, noted how unusual such recognition for a visiting player was. “It is seldom, indeed, that New Yorkers can see any good in anything that does not bear the Gotham trademark, but Wagner’s play was so great as to demand recognition anywhere.”17

One feature of the pennant race was the huge crowds all three teams drew, none more so than in New York. “The largest crowd ever” was reported more than once after Polo Grounds games in 1908. Fans on the field were not uncommon when the Giants hosted both the Pirates and the Cubs, as well as in Pittsburgh’s Exposition Park and Chicago’s West Side Grounds. And especially in New York, these fans were not simply behind ropes in the outfield.

They were everywhere. Here was one description of that July 25 crowd, reported to be 30,000. “Swung around the field on the grass and in double phalanx were spectators who filled all but about thirty of the 360 degrees of the far-flung circle.” In the ninth inning, the crowd “edged forward and penned the Pittsburg outfield to a pretty small playing space. . . . The Pittsburg outfielders couldn’t have gone back a yard for a fly ball without bumping into somebody.” Circus seats strung around the field “were intended to sit on but were used to stand on. It was a case of the survival of the tallest.”18 The New York Times described McGraw taking a bat to the fans who kept surging onto the field.19 The Times writer used more words to describe the crowd than the game itself that day. “What may have been aisles on Friday were people on Saturday, and if you weren’t there with a [boxer Jim] Jeffries punch, you looked like a long shot,” he wrote.20

After the Pirates won two games in that series and the Giants won only one (a fourth game was a 16-inning tie), Joe Vila wrote in The Sporting News, “There is no doubt that of the 70,000 persons who saw the four Pittsburg games, a large majority came to the conclusion the Giants were outclassed.”21 The month of July, in which all three teams did not play much over .500 ball, ended with the Pirates holding onto first place:

| Team | Wins | Losses | Pct. | GB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pirates | 56 | 36 | .609 | — |

| Cubs | 55 | 36 | .604 | 0.5 |

| Giants | 53 | 37 | .589 | 2 |

On August 24, the Giants arrived in Pittsburgh for a four-game series. While the Pirates were still in first, the Giants had gone on a 15-5 run to draw close:

| Team | Wins | Losses | Pct. | GB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pirates | 66 | 42 | .611 | — |

| Giants | 65 | 42 | .607 | 0.5 |

| Cubs | 64 | 47 | .577 | 3.5 |

The Giants continued their hot streak as they stunned the Pirates by sweeping the series. After New York won a doubleheader before a capacity crowd of 16,440, only 4,429 fans turned out for the third game.

Mathewson allowed one run for his 26th win in the second game. Veteran sportswriter and former ballplayer Sam Crane wrote, “Mathewson’s pitching was simply up to his class, which is the top notch of them all. He lighted up when forced to do so and showed how he is the peer of any twirler in the business. You can’t beat him — that’s all, and the game never saw his equal.”22 At a dramatic point in the game, Donlin’s celebrity wife rose and shouted, “Mike, dear, if you don’t make a hit, I will never speak to you again, and you can take back your old bracelet.”23

Mathewson allowed one run for his 26th win in the second game. Veteran sportswriter and former ballplayer Sam Crane wrote, “Mathewson’s pitching was simply up to his class, which is the top notch of them all. He lighted up when forced to do so and showed how he is the peer of any twirler in the business. You can’t beat him — that’s all, and the game never saw his equal.”22 At a dramatic point in the game, Donlin’s celebrity wife rose and shouted, “Mike, dear, if you don’t make a hit, I will never speak to you again, and you can take back your old bracelet.”23

In the ninth inning of the final game, Donlin turned to acknowledge Mabel’s words of encouragement, smiled, and singled in the tying run in a game Mathewson won in relief.24

With the sweep, it appeared that the Giants had taken control of the pennant race, and the Pirates, if not the Cubs, were done. After the doubleheader win, the reporter for the Times wrote, “Consensus of opinion is that if the NY team plays as good ball as they did today from now to the end of the League race, they will have no trouble winning the pennant.”25 C.B. Power of the Pittsburg Dispatch wrote of “the dejection that pulsated through and oozed out of the pores of Pittsburg fandom.”26

But the Pirates were not finished. On September 4, they edged the Cubs in 10 innings, 1–0. Chief Wilson got the game-winning hit, but when Pirate Warren Gill, who was on first base, did not touch second, Chicago second baseman Jack Evers insisted to umpire Hank O’Day that the run therefore did not count. O’Day did not agree. The Cubs protested. Chicago sportswriter I.E. Sanborn wrote that the protest had grown “out of Jack Evers’ ability to think faster than one bush league player and one veteran major league umpire, to wit: Pirate Gill and Hank O’Day.”27 The protest was not upheld; Vic Willis had his 18th win and Mordecai Brown was denied his 21st. The Pirates remained one-half game behind the Giants, with the Cubs now two games back

On September 16, in a win over the St. Louis Cardinals, O’Day ejected Donlin for arguing that he was safe at first base. One New York sportswriter suggested that the club’s captain was willing to be tossed because “Donlin is sore because he wants to fatten his batting average.”28 It was his sixth ejection of the season, and ex-ballplayer Crane called him out in the New York Evening Journal: “Hank O’Day is one of the very real umpires, and as such he should be appreciated by Mike Donlin. . . . Umpire O’Day should be nursed, not trampled upon. . . . I have played ball with him and against him, and I can say that no squarer man lived.”29

Mathewson saw O’Day’s stubbornness more than his fairness. In his book, Pitching in a Pinch, he wrote of the umpire, “It is dangerous to argue with him as it is to try and ascertain how much gasoline is in the tank of an automobile by sticking down the lighted end of a cigar or cigarette.”30

The Pirates came to New York for a four-game series starting on September 18. The standings that morning revealed the torrid pace of all three teams since late August.

| Team | Wins | Losses | Pct. | GB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Giants | 85 | 46 | .649 | — |

| Cubs | 85 | 52 | .620 | 3 |

| Pirates | 85 | 52 | .620 | 3 |

Since August 26, the Giants were 16-4 (.800), the Cubs were 18-5 (.783), and the Pirates were 19-6 (.760).

The series was played under an eerie and premature twilight, as smoke from upstate forest fires in the Catskills and Adirondacks had drifted down to the city.31

Once again, the series began with a doubleheader, and once again, the Giants swept. Mathewson won his 33rd game with a 7–0 shutout, and Hooks Wiltse won his 22nd. The New York Tribune saluted “the greatest pitcher in the world.” Mathewson “was master of the situation at every moment of the first game. He pitched with that beautiful precision and judgment . . . and it was absolutely impossible to rattle him.”32

The Pirates fell five games back, and the pennant seemed to be slipping away. New York newspapers celebrated the expected title. The New York Press gloated, “The Galloping Giants made secure their grasp on the National League pennant and put out of the running the Pesky Pittsburg Pirates,” who “now may be considered out of the race.”33

The Pirates fell five games back, and the pennant seemed to be slipping away. New York newspapers celebrated the expected title. The New York Press gloated, “The Galloping Giants made secure their grasp on the National League pennant and put out of the running the Pesky Pittsburg Pirates,” who “now may be considered out of the race.”33

When Donlin’s three-run home run settled matters in the first game, “the greatest crowd that ever saw a baseball game,” in the words of the Tribune, made the winning of the pennant “a foregone conclusion.”34 Even the Pittsburgh papers felt the chance had slipped away from their city’s team. “The Giants are joyous tonight because they realize it will be next to impossible for any club to snatch the pennant from their grasp,” declared one.35

There was an ugly scene during the afternoon when Donlin went into the New York crowd and brutally beat up a fan who was razzing him. It took more than one policeman to pull him off the fan, which probably saved the fan from damage.36 To the credit of the Giants’ fans, many booed and hissed at Donlin the rest of the game. Yet one New York sportswriter almost justified Donlin’s attack. He wrote that while “it was denied Donlin had attacked a fan,” he “had reason to retaliate because some chap insulted him villainously.”37

O’Day, who seems to show up in Forrest Gump-like fashion at many key games during this season, did not eject Donlin. Ralph Davis of The Sporting News saw this inaction as another example of the Giants’ intimidation of foes and arbiters alike at the Polo Grounds: “The New York Players appear to have the umpires bluffed to a standstill and are getting away with all sorts of tricks that would never be tolerated for a moment by any other aggregation. Last Friday Mike Donlin attacked one of the spectators with his fists, and it required three policemen to separate the belligerents, yet Hank O’Day lacked the nerve to even put Mike out of the game.”38 Davis went still further. “The conduct of McGraw recently has been most reprehensible. . . . The opinion is general among the base ball writers that the sooner the National League decides it can get along without McGraw and his hoodlumism, the sooner will the ideal state of affairs be realized.”39

After the doubleheader, the league’s standings confirmed the Pirates’ predicament. After play on Friday, September 18, with the Giants having completed a 26–4 run, the standings looked like this:

| Team | Wins | Losses | Pct. | GB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Giants | 87 | 46 | .654 | — |

| Cubs | 85 | 53 | .616 | 4.5 |

| Pirates | 85 | 54 | .612 | 5 |

But the Pirates steadied and took the next two games in New York. They snapped the Giants’ 11-game win streak on Saturday with a 10-inning victory, 6–2. After an off day on Sunday, Mathewson again started for New York, but lost to Willis, 2–1. The New York Sun wrote of the pitchers’ duel in which both men “made the ball talk and in a language that was Greek to most of the batters.”40

Pittsburgh scored both of its runs in the third inning, a rally started by a close call at first base, when O’Day called the Pirates’ Chief Wilson safe. McGraw argued strenuously and earned his eighth ejection of the season.41 While the New York American described O’Day’s call as “one of the worst ever seen on the grounds,” the Times again defended the umpire.42 It called O’Day “the best umpire in the game” and bemoaned “the clamor of those who are always ready to condemn the umpire should a decision go against the home team.” The writer concluded, “Perhaps he [O’Day] was right; perhaps he was wrong. Anyway, he was right on top of the play, and had a closer and better view of it than the crowd.”43

As the Pirates left New York, they had stayed relevant, if not close, for a while longer. The standings after play on September 21:

| Team | Wins | Losses | Pct. | GB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Giants | 87 | 48 | .644 | — |

| Cubs | 88 | 53 | .624 | 2 |

| Pirates | 87 | 54 | .617 | 3 |

The next day, the Giants dropped a doubleheader to the Cubs, and the day after that they played the famous Merkle game, ruled a tie. After they split four games against the Reds, the Giants had eight games with the Phillies. Rookie Phils pitcher Harry Coveleski beat them three times in the space of just five days.44 After he beat Mathewson 3–2 on October 3, the New York Press wrote, “The agonizing defeat . . . will go down in baseball history as one of the most nerve-racking games in the most desperate struggle in years for a National League pennant. Coveleski, a raw-boned coal miner . . . has done more to put the Giants out of the race than any of the veteran league stars.”45 A Pittsburgh paper hailed the pitcher who had risen “from the depths of oblivion” and added, “The name of Covaleskie will go down in history, and right here in Pittsburg the lad will be as revered as he is despised in New York.”46 After sweeping the Pirates on September 18, the Giants had gone 8–9 down the stretch, with three rainout makeup games remaining against Boston, known at the time as the Doves.

After leaving New York, the Pirates went on an 11–1 run, including a six-game home-and-away sweep of the Cardinals. As they headed to Chicago for the final game of the season, the Pirates were very much back in the race. On the morning of Sunday, October 4, here were the standings:

| Team | Wins | Losses | Pct. | GB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pirates | 98 | 55 | .641 | — |

| Cubs | 97 | 55 | .638 | 0.5 |

| Giants | 95 | 55 | .633 | 1.5 |

Since August 26, the Pirates were 32-9 (.780), the Cubs were 30-8 (.789), and the Giants were 26-13 (.667).

If the Pirates could beat the Cubs that day, the 1908 pennant would seem to be theirs. National League President Harry Pulliam had upheld the umpires’ ruling that the Merkle game was a tie, and the National League Board of Directors, due to review that ruling later in the week, was unlikely to overrule its own president. The Pirates seemed to be under the impression — widely shared among sportswriters as well — that the board would not order the Merkle game replayed, in which case the Giants would not have been able to match Pittsburgh’s 99 wins.

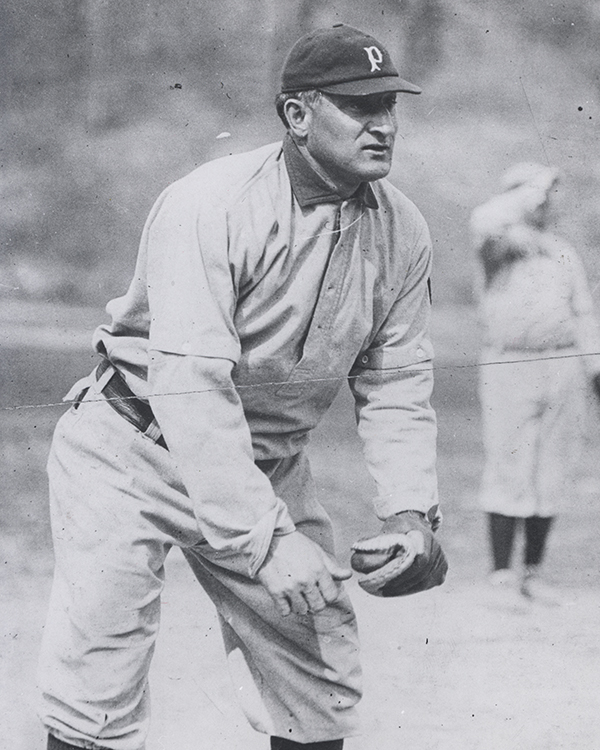

With their excellent road record and a well-rested Vic Willis (he had last pitched on September 30, throwing only three innings), the Pirates felt confident. But so were the Cubs, especially with Mordecai Brown pitching. “The composite mental attitude of the vast assemblage was quiet confidence, so great was the faith in Brown,” wrote one New York reporter.47 Sportswriter Hugh Fullerton wrote that the strain of the pennant race did not seem to show on the Chicago players. “They feel that tomorrow’s game already is won, and with Brown pitching, Pittsburgh cannot win except by accident.”48 This, despite the fact that Brown had pitched twice in the previous five days.

With their excellent road record and a well-rested Vic Willis (he had last pitched on September 30, throwing only three innings), the Pirates felt confident. But so were the Cubs, especially with Mordecai Brown pitching. “The composite mental attitude of the vast assemblage was quiet confidence, so great was the faith in Brown,” wrote one New York reporter.47 Sportswriter Hugh Fullerton wrote that the strain of the pennant race did not seem to show on the Chicago players. “They feel that tomorrow’s game already is won, and with Brown pitching, Pittsburgh cannot win except by accident.”48 This, despite the fact that Brown had pitched twice in the previous five days.

New York sports fans were in the strange position of rooting for the Cubs, to keep their pennant hopes alive. Huge crowds gathered in front of electronic scoreboards that some midtown Manhattan New York newspapers had set up, which followed every pitch. The Polo Grounds also had large boards, what the New York Times called “monster imitation baseball diamonds.”49 The Giants opened the ballpark, and thousands of people paid the 25-cent entrance fee. Among the attendees were members of both the Giants and the Doves. Fifty-thousand Pirates fans followed the game outside two Pittsburgh newspaper offices.

The enormous crowd, reported as 30,247, was declared a new baseball record, but it was destined to be a record for only 96 hours.50 “This fringe of humanity was ten or fifteen deep in the outfield,” in the words of the Chicago Daily News, “while on foul ground, running in one thick compact mass from third to first base and behind the catcher was another jam ten or fifteen deep.”51 Fullerton wrote of “two of the gamest clubs in the league locked in the death combat.”52

Even the great ones have bad days. Wagner’s throwing error in the fifth inning led to the Cubs’ second run and a 2–0 Chicago lead. The Pirates star helped tie the score in the next inning, as his double knocked in a run and he later scored. But Chicago took the lead back in the bottom of the sixth when Brown hit a two-out single after the Pirates had walked the dangerous Johnny Kling intentionally. The Cubs scored again in the seventh, with a rally that began when Wagner fumbled a routine ground ball and let it get between his legs.

With the Cubs up 5–2 going into the ninth, Pittsburgh generated drama and controversy. After a leadoff single by Wagner, Ed Abbaticchio hit a drive down the right-field line. O’Day was the umpire behind home plate, and he called the ball foul. “At first, umpire O’Day seemed to wave the runners on to their bases,” wrote the Chicago American.53 The Pirates thought it was a fair ball and quickly rushed to encircle O’Day, who held his ground. They then appealed to the other umpire, Cy Rigler. The Pittsburg Post writer said that Rigler first told “Abby” that the ball was fair.54

Rigler was almost certainly standing near second base, the proper position of the second man in a two-umpire team, and would have had a poor angle on the ball. But the reality was even more problematic. With fans on the field, the foul line was likely obscured. “The ball went into the crowd on the line,” said the account in the Examiner.55 Rigler eventually upheld O’Day’s call, Abby struck out, and the Pirates went quietly.

For the same reasons the Pirates and others thought a win would guarantee them the pennant, it was widely accepted that the loss had eliminated them. Without a makeup of the Merkle game, they would finish a half-game behind the Cubs. The standings at the end of the day:

| Team | Wins | Losses | Pct. | GB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cubs | 98 | 55 | .641 | — |

| Pirates | 98 | 56 | .636 | 0.5 |

| Giants | 95 | 55 | .633 | 1.5 |

Wagner was disconsolate; he said he would have traded his personal achievements for a pennant. The New York Times headline read, “Hans Wagner Heartbroken; Will Kill 10,000 Birds This Winter Trying to Forget Pirates Defeat.” The team dispersed, their season, they believed, at an end. Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss went into the Chicago clubhouse, congratulated the Cubs, and added that somebody had to lose. “You are a better loser than I am . . . You are the best loser in the league,” Chicago owner Charles Murphy sarcastically replied.56 Pittsburgh player-manager Clarke said to Chance, “I want to congratulate you, Frank. It was a great game. . . . We’ll be back at you next year.”57 The Cubs would improve to 104 wins in 1909, but the race would not be close, as Clarke’s Pirates would win 110.

The Giants had three games remaining with the Doves, starting Monday, October 5. The league’s directors still had to rule on the Merkle game, which their president had ruled a tie. Chance expressed confidence the pennant would belong to his club, but so did John McGraw. If his Giants would not be awarded the tie game, they would beat Chicago “in the playoff, whether it be one game or three,” he said.58

Most fans of baseball history know that the Giants did go on to sweep Boston, only to lose a replay of the Merkle game — and the pennant — to the Cubs. But overlooked in the story is the strange and confounding situation that could have developed.

First, had the National League Board of Directors overruled President Pulliam and awarded the Merkle game to the Giants, and had the Giants won two of three against the Doves, the final league standings would have looked like this:

| Team | Wins | Losses | Pct. | GB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cubs | 98 | 56 | .636 | — |

| Pirates | 98 | 56 | .636 | — |

| Pirates | 98 | 56 | .636 | — |

On Tuesday afternoon, October 6, the Board of Directors of the National League upheld Pulliam’s ruling (which upheld the umpires) that the Merkle game was indeed a tie and announced that the game would be replayed at the end of the season — even if the Giants lost a game to the Doves and finished the season a game behind Chicago.

The ruling declared, “We realize the great importance that the game in question may be in determining the winner of the championship in the National League.”59 It also stated, “We hold that the New York club should, in all justice and fairness, under these conditions be given the opportunity to play off the game in question.”60 The National League’s owners had ruled that the Giants deserved a chance to replay the Merkle game.

While the Giants would sweep the Doves (the author delivered a paper at the 2012 SABR national convention that raised questions about the legitimacy of that series), the chronology is significant. While New York won the first game on Monday, they were leading by only a 1–0 score in Tuesday’s game. With a 3:30 start time for games at the Polo Grounds, the afternoon ruling was handed down when the game was very much in doubt, if not before it had begun. And Wednesday’s game saw the Giants fall behind 2–0 early.

Only some observers and reporters realized that the ruling could cause “an awful muddle,” in the words of one Pittsburgh paper.61 The possibility of a three-way tie for the pennant was a distinct possibility. One New York paper grasped the implications of the ruling and explained it well:

By making it mandatory to play the game tomorrow, the Giants have a better chance than if the contest had been decided a tie, and the controversy closed. . . . A defeat by Boston now will not affect the New York-Chicago game, which must be replayed.

New York now has two chances to win the pennant, where formerly they had only one. If the Giants beat Boston today, they will tie Chicago. . . . The winner of tomorrow’s game will then be champions of the National League. Should, however, New York lose the remaining game with Boston, the Chicago contest will follow. If the Giants should prove successful against the Cubs after losing to Boston, a three-cornered tie would result.62

Had the Giants dropped a game against the Doves, the standings at the end of play on Wednesday, October 7, would have looked like this:

| Team | Wins | Losses | Pct. | GB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cubs | 98 | 55 | .641 | — |

| Pirates | 98 | 56 | .636 | 0.5 |

| Giants | 97 | 56 | .634 | 1 |

The Merkle game would still have been replayed, and had the Giants beaten the Cubs in that game on Thursday, the standings would have been the three way tie at 98-56 referenced above.

The headline in Monday’s Pittsburg Leader, reflecting this possibility, read, “One Faint Last Hope.” Wednesday’s Pittsburg Dispatch noted the possibility of that tie and declared, “Well, the Pittsburg Club has disbanded, and it is hard to tell what we would be able to do.”63 Even if they could regroup, league rules required three best two-of-three playoffs. In a round-robin, each of the three teams could have won three games and lost three.

After the fact, The Sporting News railed against the ruling, arguing in an October 15 editorial that the board had “exceeded its authority in ordering a championship game to be played off after the close of the regular race to settle a tie for first place. The [National League] constitution imposes on the directors the duty of arranging a special series of three games between the tied teams.”64

The following spring, the 1909 Spalding Baseball Guide stated, “There was still another embarrassing feature to the order to play one game to settle the New York and Chicago tie. That was, that if the Giants should have happened to have lost one game in Boston, and then should have beaten Chicago, there would have been a three-cornered tie for the championship between New York, Pittsburg, and Chicago. That was feared in some quarters but did not materialize.”65 Sportswriter Fred Lieb confirmed this possibility in his history of the Pirates.66

The ruling had given the Pirates a lifeline, but Dreyfuss did not seize it. The Pirates owner was not allowed to vote in the Board of Directors meeting (just as John Brush of the Giants and Charles Murphy of the Cubs were excluded) because he had a direct interest in the outcome. Yet he said that had he been able to vote, he would have voted that the Merkle game be awarded to the Cubs, which would have given them the pennant. Dreyfuss had an intense dislike of McGraw and called the board’s ruling “a sickening case of ‘straddling’ and trying to avoid the issue.”67 He even said the Cubs should refuse to play the replay of the Merkle game.

Fortunately for the National League, the Giants swept the Doves, the possibility of a three-way tie was averted, and the Pirates were eliminated — again. So why did the league risk such chaos and give the Giants two opportunities to win the pennant? Neither Pulliam nor the team owners explained the ruling, and Pulliam took his own life less than 10 months later, at least in part over the stress of the Merkle game controversy. “No one can tell precisely how much all these vicissitudes had to do with Pulliam’s suicide the following July,” wrote Harold Seymour and Dorothy Seymour Mills, “although undoubtedly they played their part.”68 Perhaps Pulliam tilted toward the Giants to avert or at least minimize the explosive reaction of McGraw and Brush, should their Giants fall short of the pennant.

STEVE STEINBERG is a baseball historian of the early twentieth century. He has co-authored two award-winning books with Lyle Spatz, “1921” and “The Colonel and Hug.” His Urban Shocker biography was awarded the 2018 SABR Baseball Research Award. His latest book, “The World Series in the Deadball Era,” is a joint effort of SABR’s Deadball Era Committee. Steve has also published more than 20 articles, many in SABR journals.

Notes

1 Cait N. Murphy. Crazy ’08: How a Cast of Cranks, Rogues, Boneheads, and Magnates Created the Greatest Year in Baseball (New York: HarperCollins, 2009), 245.

2 New York Sun, April 12, 1908, as quoted in G. H. Fleming, The Unforgettable Season (New York: Penguin Books, 1982).

3 Christy Mathewson, New York American, August 9, 1908, as quoted in Fleming, 161-62.

4 David W. Anderson. More than Merkle: A History of the Best and Most Exciting Baseball Season in Human History (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2000), 120.

5 Craig R. Wright and Tom House. The Diamond Appraised (New York: Fireside, 1989), 389.

6 Michael Betzold and Rob Edelman, “Mike Donlin,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/3b51e847. See also Charles C. Alexander, John McGraw (New York: Viking, 1988), 124-25.

7 New York Evening Mail, August 1, 1908, as quoted in Fleming, 147.

8 New York World, August 9, 1908, as quoted in Fleming, 161.

9 James Crusinberry, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 17, 1908, as quoted in Fleming, 172.

10 Ralph S. Davis, “Fought to Finish,” The Sporting News, October 8, 1908. At the time, the official spelling of Pittsburgh omitted the final h.

11 Sporting Life, July 18, 1908.

12 “Wagner’s Wonderful Work Won Game for Pittsburg,” Pittsburg Leader, May 12, 1908.

13 William F. Kirk, New York American, June 12, 1908, as quoted in Dennis and Jeanne DeValeria. Honus Wagner, A Biography (New York: Henry Holt, 1998), 180.

14 “Leach’s Home Run wins for Pirates,” New York Press, July 11, 1908.

15 “Mathewson is Knocked Out of Box,” New York Evening Telegram, July 26, 1908. Wagner hit three singles and two doubles.

16 “Great Crowd Sees New York Lose,” New York Tribune, July 26, 1908.

17 Davis, “Two Series Over,” The Sporting News, August 6, 1908.

18 “Pirates Drub the New Yorks,” New York Sun, July 26, 1908.

19 W.W. Aulick, “Record Crowd Sees Giants Routed,” New York Times, July 26, 1908.

20 Aulick.

21 Joe Vila, “Beat Weak Teams,” The Sporting News, August 6, 1908.

22 Sam Crane, New York Evening Journal, August 25, 1908, as quoted in Fleming, 183.

23 Crane.

24 “Brilliant Finish Wins for Giants,” New York Times, August 27, 1908.

25 “Giants Now Lead for the Pennant,” New York Times, August 25, 1908.

26 C.B. Power, “Giants Make It Four Straight, Winning in the Ninth Inning,” Pittsburg Dispatch, August 27, 1908.

27 I.E. Sanborn, “Cubs Will File Protest,” Chicago Tribune, September 5, 1908. Gill played only 27 games in his major-league career.

28 “Giants Drive New Pitcher to Bench,” New York Times, September 17, 1908. O’Day ejected 13 men that season.

29 Crane, New York Evening Journal, September 17, as quoted in Fleming, 222-23.

30 Christy Mathewson. Pitching in a Pinch: Baseball from the Inside (Lincoln: Bison Books, 1994), 175.

31 “Pirates Turn Tables on the Giants,” New York Tribune, September 20, 1908.

32 “Giants Pennant Bound,” New York Tribune, September 19, 1908.

33 “29,000 Persons See Giants Rout Pittsburg Twice,” New York Press, September 19, 1908.

34 “Giants Pennant Bound.”

35 “Crowd Numbering 32,000 Sees Pittsburg Team Practically Lose the Pennant,” Pittsburg Post, September 19, 1908.

36 “Giants’ Bats Crush Pittsburg Team,” New York Times, September 19, 1908. The Times has a vivid description of Donlin’s attack.

37 New York Evening Telegram, September 19, 1908.

38 Davis, “Played Poor Ball,” The Sporting News, September 24, 1908.

39 Davis, “Hard Trip Ahead,” The Sporting News, September 17, 1908.

40 “Willis Trips New York,” New York Sun, September 22, 1908.

41 Retrosheet currently has McGraw with 118 ejections as a manager. This number may grow as more box scores are added to the database.

42 William F. Kirk, New York American, September 22, 1908, as quoted in Fleming, 237. It is odd that McGraw was ejected by home-plate umpire Bill Klem, and not by O’Day. But the writer for the Pittsburg Dispatch, C.B. Power, explained that after McGraw made “some awfully hateful remark” about O’Day to Klem, the latter stood up for his fellow umpire and ejected McGraw.

43 “Pirates Beat Giants,” New York Times, September 22, 1908.

44 Coveleski appeared in four games in 1907 and six in 1908. Besides his three victories over the Giants, he won only one other game that year. His only decision in 1907 had come against the Giants.

45 “Giants Lose Grip on Pennant when Mathewson Fails to Check Phillies,” New York Press, October 4, 1908.

46 Ernest E. Mooar, “Pirates are Favorites in Remarkable Fight for National Pennant,” Pittsburg Leader, October 4, 1908.

47 “Cubs, by Beating Pirates, Now Lead National League,” New York Press, October 5, 1908.

48 Hugh Fullerton, “The Pirates in Battle for Pennant Today,” Chicago Examiner, October 4, 1908.

49 “Fans at the Polo Grounds,” New York Times, October 5, 1908.

50 The replay of the Merkle game drew around 40,000 fans. The attendance for the October 4 game broke the West Side Grounds record by around 6,000. The first game of the 1907 World Series drew 24,377 fans.

51 Chicago Daily News, October 5, 1908.

52 Fullerton, “Brown Leads Champions in Thrilling Climax of Season,” Chicago Examiner, October 5, 1908.

53 Chicago American, October 5, 1908.

54 “Buccaneers are Welcomed Home,” Pittsburg Post, October 6, 1908.

55 “Story of Cub Triumph over Pittsburg Told Play by Play,” Pittsburg Examiner, October 5, 1908. The Chicago American stated that Rigler was “working on the foul line right back of first base.”

56 DeValeria, Honus Wagner, 196.

57 Harvey T. Woodruff, “Cubs Jump to Top, Beating Pirates,” Chicago Tribune, October 6, 1908. The Giants would finish 18 1/2 games back. Perhaps because they were not in the race, John McGraw argued less with umpires than in previous seasons, with only three ejections.

58 “Doves Out to Help the Cubs Win Pennant,” Chicago American, October 5, 1908.

59 “Must Play Off Tie,” Chicago Tribune, October 7, 1908.

60 “Pulliam’s Tie Game Decision Upheld,” New York Times, October 7, 1908.

61 “Monster Baseball Muddle Confronts National League,” Pittsburg Leader, October 7, 1908. See also “Race Undecided at Season’s End,” Pittsburg Chronicle-Telegram, October 7, 1908.

62 “Pulliam’s Tie Game Decision Upheld,” New York Times, October 7, 1908.

63 “Giants and Cubs Ordered to Play Off Tie Game,” Pittsburg Dispatch, October 7, 1908.

64 Editorial, The Sporting News, October 15, 1908.

65 John B. Foster, editor, Spalding Baseball Guide 1909, 111.

66 Frederick G. Lieb. The Pittsburgh Pirates (Carbondale: University of Southern Illinois Press, 2003), 128.

67 Power, “Giants and Cubs Ordered to Play Off Tie Game,” Pittsburg Dispatch, October 7, 1908.

68 Harold Seymour and Dorothy Seymour Mills, Baseball: The Golden Age (New York: Oxford University Press, 1971), 27.