Babe Ruth and the Boston Braves: Before Opening Day 1935

This article was written by Carolyn Fuchs - Wayne Soini - Herb Crehan

This article was published in The Babe (2019)

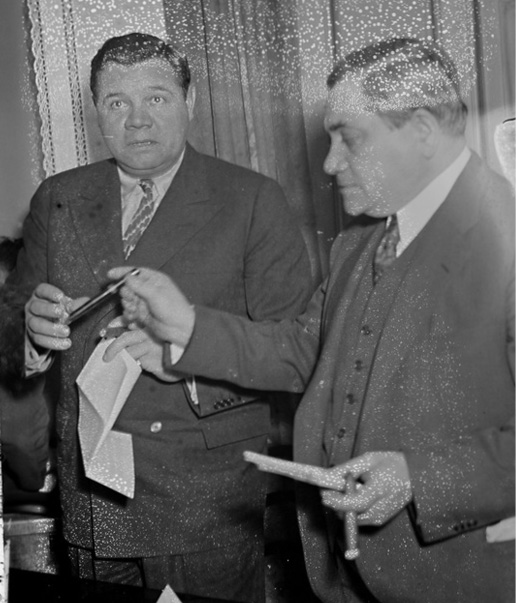

Babe Ruth and Boston Braves executives in a Copley Plaza Hotel room, after signing with the Boston Braves, February 28, 1935. (l to r): Charles F. Adams, Babe Ruth, and Judge Emil Fuchs. (Leslie Jones photo, courtesy of the Boston Public Library.)

When George Herman “Babe” Ruth arrived in St. Petersburg in 1935 for spring training with the Boston Braves, his illustrious career had come full circle. Twenty-one years earlier the Babe had joined the Red Sox in Boston as an impressionable 19-year-old pitcher. During the intervening years Babe had won 89 games as a pitcher for the Red Sox, set a World Series record for consecutive scoreless innings that would stand for 43 years, and slugged over 700 home runs leading major-league baseball from the Deadball Era to the Lively Ball Era. He had gained international acclaim. There was a candy bar named after him and anything that was too large to describe in words was termed “ruthian.” Whatever the opposite of impressionable is, the Babe was it in 1935.

He was also in many ways no longer ruthian. Five years before, at age 35, the Babe had led the American League with 49 home runs. In 1934 his home-run total had fallen to just 22. Babe Ruth’s value had tanked as the proverbial “fat and forty” man. Everyone who owned a team knew this and almost every owner concluded against offering a contract to the Babe – all but one – the Judge: Emil Fuchs, owner of the Boston Braves.

Although hoary baseball mythology casts Babe Ruth’s 1935 availability to the Boston Braves as the beleaguered Braves owner’s last chance to hold onto his team, the opposite is true. The Judge was the Babe’s last chance to play ball – or to gain a toehold in management.

The latter was the big draw for Ruth, who had made it known that he wanted to manage. In his excellent biography of Ruth, The Big Bam, Leigh Montville recounts a meeting between Babe, Yankees owner Colonel Jacob Ruppert, and general manager Ed Barrow right after the end of the 1934 season. Montville claims that Ruth asked the two decision-makers if they intended to return manager Joe McCarthy for the 1935 season. When told that they had already decided to bring back McCarthy, Babe is reported to have said, “That’s all I wanted to hear,” and stormed out of the meeting.1

The Judge had not been first in line for the stormer. As Montville further documented, the Philadelphia Athletics’ owner-manager, Connie Mack, had resolved to sign Ruth as the manager of the A’s for the 1935 season. But Mack made it a point to observe the Babe closely as the 1935 season approached and he quickly realized that Ruth had great difficulty managing himself, let alone a ballclub.2 When the Yankees formally released the Babe, the owners of every team in both leagues had to sign waivers. They all did, including Connie Mack. Ultimately, nobody wanted the Babe but the Judge.

What then led the Judge to take on the Babe? The short answer is the Judge’s unusual personality. He was hot-potato-proof. Unique among owners from the start of his ownership in 1923, he never worried.3

By rights the Judge ought to have worried. When he took them over, the Braves were plainly the weaker of Beantown’s two clubs. While large populations in New York and Chicago could support two teams – Brooklyn even supported a third in New York – the Judge fought for fans in far smaller Boston. Boston was a city really only big enough for one ballclub. (And not only Boston. As if to prove the fact that they were one-team towns, Philadelphia, St. Louis, and Boston all shed one of their two teams in the mid-1950s. The Judge struggled long and hard against odds that would eventually defeat anybody.)

In part, this did not worry the Judge at first because his day job as a busy New York lawyer supported him and his family in style on Riverside Drive. He did not get into baseball for money. The Judge’s initial objective was to enable Christy Mathewson to pursue professional baseball as a team president and owner. He idolized Christy, with whom he’d become close while serving as the lawyer for the New York Giants. He made Christy the president of the Braves. If the team’s fortunes improved, Christy could buy out the Judge and become the owner of the Braves. Things did not play out as planned

Given time, the Judge’s hopeful plans for Mathewson may have worked out but Christy’s health – his lungs had been ruined by exposure to poison gas during World War I – deteriorated too quickly for a fair trial. Mathewson’s death in 1925 simultaneously left the Judge mourning a friend and becoming the sole owner of a major-league ballclub.

Rather than sell, the Judge banked on raising the team’s morale, record, and dismal standings before he sold the Braves. He set no time limit. The Judge did not close his law office and still fully intended to go back to practicing law full-time in New York as the Twenties spilled over into the Thirties. The Braves improved. For example, the team made $150,000 in 1933, even after the Judge paid himself a salary of $30,000. That was the same season the Braves rose into serious contention for the pennant. Huge Braves Field was sold out for some games, with standing room only. The Braves attracted national attention and some bids came in. Auto baron Henry Ford was moved to offer the Judge one of his spare millions for the team. Incredibly, the Judge declined to sell. Ever optimistic, he was becoming a believer. Like many fans, the Judge preferred “Next year!” The decisive year, the Judge determined, would be 1934. After all, wasn’t Henry Ford a good businessman? If so, didn’t it make sense to hold on to a good thing? The Judge poured his 1933 profits and a good deal more into his bouncing Braves.

The effort fizzled spectacularly. For the Judge, 1934 had not been so much scary as sad.

“There is nothing more tragic than to be playing to almost empty seats in a ballpark that holds almost 45,000 people,” the Judge confided when interviewed in his retirement years.4

The Judge had tried everything else to raise revenue. Sunday baseball, Ladies’ Days, the Knot Hole Gang, and live radio broadcasts of Braves games were among the Judge’s innovations or adaptations. Not every experiment worked. “Music at the Ballpark” proved a sour note when, in 1930, the Judge hired musicians to play before and after games. The bonus of classical and popular pieces drew nobody to Braves Field.5 Another deal worked out surprisingly – when it failed. The Judge rented Braves Field to the operators of that grand old sports emporium, the Boston Garden. It was to be used for outdoor boxing matches. He sagely negotiated a five-year deal. At $30,000 a summer, after losing money after two seasons, the Garden’s field of dreams was on the ropes. The Garden bought out its contract. The imperturbable Judge then scouted for another tenant. In 1934, he toyed with the potential of an offseason greyhound track. Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, always death on any link between baseball and gambling, squelched the proposal.

Another thing helped. Having taken out large loans (something over $200,000) with Braves stock and his optimism the only collateral, the redoubtable Judge got the National League to guarantee his team’s annual rent on Braves Field in 1935. It took a marathon special meeting of owners in December 1934, but it was done. Before mention of the Babe, everything was in place for the Braves to play ball on Opening Day in 1935. With luck in 1935, the Judge would make money as he had in both 1932 and 1933.

The Judge was well aware of the Babe’s continuing popularity in Boston. Some 48,000 fans had packed Fenway Park to see, in tears and with cheers, the Babe’s last game in Boston. In New York the following month, as the season ended anticlimactically, a mere 2,000 people watched his last at-bat in a Yankees uniform.6

Tipped off by Colonel Ruppert of the Babe’s availability, the Judge made no effort to sweet-talk the Babe when he called him. He had Colonel Ruppert’s okay to speak frankly. The Judge spoke in a “Dutch uncle” manner concerning any move into management. He said that the job of managing was hard, that the Babe would have to master new skills and that the current Braves manager, Bill McKechnie, was a good man to learn from.

The Babe realized that this was the best deal he was going to get from anybody. The Yankees sent him everything but a telegram. The season before, the Babe had his salary cut by $17,000.7 Nobody else was calling. The Judge represented his only chance at extra innings in the game. The two men agreed and paperwork followed.

The deal solved a big team problem. The Yankees did not have to fire the Babe. He simply left and put on a Braves uniform. Their relief was most clear many years later. The Yankees manager, Joe McCarthy, sat at a dinner in a Boston restaurant in the 1940s, treating Judge Fuchs and his family. McCarthy asked the assembled Fuchs family if any of them knew why he felt so fondly toward the Judge. The Judge’s sister, Helen, took a guess. “Because he took Babe Ruth?” she asked. McCarthy smiled and nodded.8

Listening only partially as the Judge spoke, the Babe seems in retrospect to have heard the word “manage” and then paid little or no attention to warnings or conditions. That is, he was offered a year as assistant manager, much like an intern watching McKechnie. He might learn and prove himself fit for the job or he might not. Showing obliviousness, the Babe had no questions about that proposal. Instead, he asked for an unprecedented cut of the Braves’ exhibition games. Unfazed, the Judge granted him 25 percent.9 The Babe’s appearances would likely bring more fans to those games, perhaps enough to make up for his unheard-of cut.

Babe Ruth and Boston Braves owner Judge Emil Fuchs exchange the newly signed contract for Ruth to play with the Braves. (Leslie Jones photo, courtesy of the Boston Public Library.)

As for the Judge, he neither had a management problem nor did he want to create one. (If the Judge ever really needed a manager, he could fill in himself. He had managed the team in 1929 by assembling a “Brain Trust” to advise him. And he could spot management talent from afar – he gave Casey Stengel his first manager’s job in 1925.) Not unlike most baseball insiders, he did not see Babe Ruth as a manager. But, in Babe’s best interests, the Judge saw farther out. He concluded that the Babe himself would abandon his unrealistic ambition before very long. The Judge created time, a full season, for the Babe to shadow McKechnie, to observe and to take in what it took to manage. What would happen? Realistically, the Judge expected the Babe to make a transition from player to the front office instead. He gave him, unasked, another job as the team vice president.

“I didn’t promise him he would be a manager,” the Judge told a sports reporter with more specificity years later than was possible in 1935. “In fact, I told him Bill McKechnie was my friend and suggested that he didn’t want to become a manager, that he’d be better off an executive. That’s why I made him vice president.”10

As soon as negotiations by phone between Boston and New York concluded, the Judge wrote up a letter in which he memorialized their conversation and the offer that the Judge was making. The letter is preserved. Its terms were published in newspapers at the time. Anybody who could read knew that the “management” term of the three-year deal was only good for the first year, and that slot was as “assistant manager in 1935.”

Thus both acknowledging what the Babe desired as well as preparing him for a potential turn instead to the front office, the Judge gave The Babe a practical contract. He would play, of course, and, if he wished, take a long mental stab at managing. But also, as he carried goodwill with him wherever he went, the gregarious Babe should thrive in a state where he was not only idolized but beloved. As vice president, in a suit rather than a uniform, the Babe would move blocks of ticket by signing baseballs at department stores. He would be the highly visible representative of the team, and a key revenue-producer.

To check out his theory of The Babe’s Boston popularity, the Judge invited the Babe to join him on his next trip up to Boston from New York. This train trip to Boston (on February 28, 1935) became big news. It was a much-anticipated photo opportunity but much more: Fans in droves arrived at Back Bay station to catch a glimpse of their favorite player, the legendary Babe.

At Back Bay, adulation moved notches beyond anything the Babe experienced before, even as a winning World Series pitcher for the Red Sox in 1918. Waves of cheers and a seemingly endless, thunderous applause greeted him.

At a hotel banquet that night, a businessman with multiple sports investments, including the Braves, spoke up prophetically. Charles Adams, owner of the Boston Bruins and some of Suffolk Downs, a partner in the Braves who fronted money when the Judge needed it, was on edge about the deal. He plainly trusted the Judge more than he did the Babe. And he had an investment to protect. By 1934, the Judge owed Adams $200,000. Adams was the most clear-minded of the speakers who rose to toast the Babe that night.

Adams warned, “Babe Ruth will become manager of the Braves only when he proves he is capable of filling the post. Current manager Bill McKechnie will be the absolute boss on the field this season.”11

With a Dutch-uncle phone call, a road map to the front office, and Adams’s very public warning, the Babe’s baseball career resumed in Boston, where it had begun. But the returning hero, the Babe, really only felt at home now in New York. Strutting about as one of New York’s foremost celebrities, he threw himself into a lively social life for obvious reasons: Given physical decline, he lived more for his time off the field.

Curiously, the Judge was hardly less of a New Yorker than the Babe. Although born in Germany, Emil Fuchs grew up to play on the immigrant kids’ Settlement House baseball team before World War I. After he became a lawyer, he was the team attorney for the New York Giants and he regularly cheered from the best seats on the Polo Grounds. It was in New York that the Judge got a partnership together to buy the Braves in order to bring Christy Mathewson back into baseball. New York retained a hold. The Judge commuted between New York and Boston for years until he decided to go all in and buy out his partners. He was not a rich man, but the team had never repeated its 1914 miracle and, in the cellar of the league, was to be had cheaply. The Judge loved baseball enough to justify an expensive hobby, even if it would – and it ultimately did – cost him his house.12

In 1935, after spring training in St. Petersburg, when the Braves arrived in Boston in mid-April, their first game was at Fenway Park against the Boston Red Sox. The kickoff of the then-annual City Series, exhibition games between the traditional crosstown rivals showcased the Babe’s formal return. His first appearance in a Boston Braves uniform, ironically enough at Fenway Park, drew only 11,000 fans. This was an ominous sign just as the regular season neared. What next?

On Opening Day at Braves Field on April 16, 1935, the Boston Braves, now with Babe Ruth, playing against the New York Giants, would start giving the answers.

CAROLYN R. FUCHS, M.Ed, has baseball in her blood. She in the granddaughter of the late Judge Emil Fuchs. Her dad Robert Fuchs wrote a book about the Judge and the Boston Braves. Carolyn heard first-hand from her father Robert about the Judge. She is a member of the Boston Braves Historic Society and continues to write and support articles about the Braves during the Judge Fuchs era. She provides the silver tray annually at the Boston Baseball Writers Association where the last award of the evening is the Judge Emil Fuchs Award for “long and meritorious service to baseball” presented to a recipient selected by the baseball writers.

WAYNE SOINI, a lifelong history buff, holds a master’s degree in History from the University of Massachusetts Boston. Prior to publishing two historical novels, Nixon in Love and Germany Surrenders! in 2015, Soini coauthored a local sports history book with Robert Fuchs, Judge Fuchs and the Boston Braves (McFarland, 1998), Gloucester’s Sea Serpent (History Press, 2010) and Porter’s Secret.

HERB CREHAN is one day younger than Rico Petrocelli and attended his first Red Sox game in 1952—a doubleheader against the St. Louis Browns! He is in his 24th season as a contributing writer for Red Sox Magazine, the team’s official program. He has interviewed over 140 former Red Sox players during his 24 seasons of writing the series, “Native and Adopted Sons of New England’s Team.” He publishes and maintains the website www.bostonbaseballhistory.com and he has been a member of SABR since 1995.

Notes

1 Leigh Montville, The Big Bam: The Life and Times of Babe Ruth, (New York: Doubleday, 2005), 52.

2 Ibid.

3 Judge Fuchs was inclined to be imperturbable. Christy Mathewson noticed that the Judge crossed city streets with uninterrupted steps, even if cars brushed close by him. He wondered aloud how many hours a year the Judge saved by not worrying about being hit. (Anecdote from Robert S. Fuchs, shared orally with Wayne Soini in about 1996.)

4 Cullen Cain, “Giants, Braves Had to Move,” Miami News, July 12, 1958. (Clipping in the scrapbook in possession of Carolyn Fuchs, granddaughter of Judge Fuchs.)

5 Burt Whitman, “Judge Fuchs Hopes Music at Braves Field Will Strike Responsive Chord with Fans,” Boston Herald, January 17, 1930.

6 Figures from Allan Wood, “Babe Ruth,” sabr.org/bioproj/person/9dcdd01c (accessed June 15, 2018).

7 Ibid.

8 Robert S. Fuchs and Wayne Soini, Judge Fuchs and the Boston Braves, 1922-35 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1998), 100.

9 Fuchs and Soini, 106, 110. (The Yankees also allowed Ruth to continue to receive his share of exhibition games in 1935.)

10 Tom Monahan, “Mrs. Ruth Hits Yankees, Fuchs, Hub Writers,” Boston Traveler, March 4, 1959: 28.

11 Fuchs and Soini, 107.

12 The Judge had settled in Jamaica Plain, not far from Boston Mayor Curley’s home. When he could not pay the mortgage, the family rented an apartment in the Back Bay neighborhood.