The Honor Rolls of Baseball

This article was written by David Fleitz

This article was published in 2005 Baseball Research Journal

Who deserves to be inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame, and who does not? The Hall of Fame electors wrestle with this question every year. The selection process for players causes controversy on an annual basis, but the institution, since its inception, has also grappled with the issue of recognition for non-playing contributors. Some believe that Hall membership should be reserved for players alone, while others contend that executives, umpires, managers, and sportswriters deserve equal acknowledgment. The Hall of Fame has modified its eligibility rules for both playing and non-playing personnel numerous times over the years, and many of those changes have drawn waves of criticism in the press. “It appears,” stated an editorial in The Sporting News after one Hall election, “that the entire Hall of Fame scheme is in need of a complete overhauling.”

The erstwhile “Bible of Baseball” was not referring to the electoral changes of the last few years. Rather, the above statement appeared in the weekly newspaper nearly 60 years ago, after the Hall of Fame made an ill-advised attempt to honor non-playing contributors to the national pastime. On April 23, 1946, the Hall of Fame’s Permanent Committee (which evolved into the now familiar Veterans Committee) announced the selection of 11 old-time players to the Hall of Fame. The committee also revealed the names of 39 others – managers, executives, umpires, and sportswriters – to the new “Honor Rolls of Baseball.”1

In creating the Honor Rolls, the Hall constructed a second level of induction. It allowed the Hall to recognize the accomplishments of a non-playing contributor without according him the same status (that is, a plaque on the wall) as a Babe Ruth or a Ty Cobb. The Honor Rolls also marked the first attempt by the Hall of Fame to create an appropriate recognition for the contributions of sports writers, although the concept was roundly criticized and was ultimately judged a failure. Before long, the Honor Roll award died of neglect, and it is almost completely forgotten today.

Background

When the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum was created in the mid-1930s, Commissioner Kenesaw M. Landis gave the right to select honored players to the Baseball Writers Association of America. Two hundred and twenty-six sportswriters participated in the first election, held in January 1936, and named Ty Cobb, Babe Ruth, Honus Wagner, Christy Mathewson, and Walter Johnson to the Hall. In 1937 the writers elected Tris Speaker, Napoleon Lajoie, and Cy Young; in 1938 only Grover Cleveland Alexander gained enough votes for enshrinement; and in 1939 George Sisler, Willie Keeler, and Eddie Collins joined the others.

At the same time, the Hall of Fame debated the issue of electing early players, executives, and other deserving contributors. A separate election for 19th-century players was held in 1936, but the voting process was not well planned. When no one gained the required number of votes for selection, sports columnists across the country criticized the Hall of Fame electors for ignoring the contributions of early players.

In response, Landis appointed a committee consisting of himself, the two league presidents, a retired league president, and the president and chairman of the minor leagues. This was called the Centennial Commission, and was given the responsibility of electing 19th-century players and builders of the game to the Hall. This committee elected seven men to the Hall in 1937 and 1938, including the first baseball writer, Henry Chadwick. In 1939 a smaller committee consisting of Landis and the two league presidents elected six more men, including old-time players Cap Anson and Buck Ewing, to the Hall of Fame.

Questions about the committee choices arose early in the selection process. In December 1937 the Centennial Commission selected managers Connie Mack and John McGraw, league presidents Ban Johnson and Morgan Bulkeley, and early shortstop George Wright to the Hall. Some sportswriters, led by Richards Vidmer of the New York Herald Tribune, suggested that the members of the committee might have confused George Wright with his brother Harry, the first professional baseball manager, whom they saw as a more deserving candidate.2 In any event, George Wright had died only a few months before, and his selection marked the first instance of a Hall candidate being helped by the “death effect,” a boost in a candidacy caused by a recent demise.

Some observers also criticized the enshrinement of Morgan Bulkeley, who served as National League president for only ten months. Bulkeley was nothing more than a figurehead, but was selected to the Hall of Fame because he was the first National League leader. William Hulbert, the true creator of the league, was not elected until 1995.

After the 1939 selections were made, Commissioner Landis appointed a new four-man board, the Old-Timers Committee, charged with electing players and contributors from the distant past. This board consisted of Philadelphia Athletics manager Connie Mack, executives Ed Barrow and Bob Quinn, and veteran writer Sid Mercer. However, from 1939 to 1944, this committee could never arrange a meeting to elect new members to the Hall of Fame. In the meantime, the BBWAA decided to vote every three years instead of every year. It elected Rogers Hornsby in 1942 and no one else from 1940 to 1947.

In 1944, after the Hall had inducted only one man in the previous five years, Landis made significant changes to the Old-Timers Committee. He added two more members, Boston writer Mel Webb and Hall of Fame president Stephen C. Clark. Landis also empowered the committee members to act as trustees of the institution, allowing them to set policy concerning the selection process for Hall of Fame honorees. The committee, renamed the Permanent Committee, met for the first time in December 1944 and named the recently deceased Landis to the Hall.

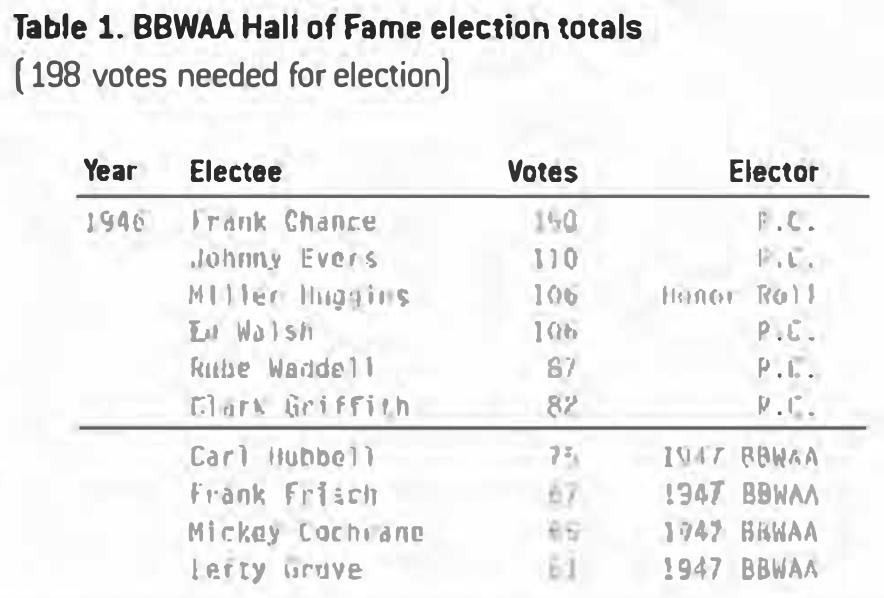

The Permanent Committee exercised its power for the first time in 1945. In January of that year, the BBWAA held its first vote since 1942. Because of the large number of qualified candidates, the voting was widely split among many deserving players, and no one managed to gain the required number of votes for election to the Hall. In response, the Permanent Committee met on April 25, 1945, and unilaterally elected what Bill James called “a bargeload of 19th-century guys” to the Hall of Fame.3 At one stroke, 10 new Hall of Famers entered the doors of Cooperstown. The Committee, much to the dismay of the BBWAA, also gave itself the responsibility for electing players whose careers extended up to 1910.

The Permanent Committee hoped that this move would clear up the voting stalemate, but it did not. In January 1946, after the BBWAA decided to resume its annual voting, it once again failed to elect anyone to the Hall of Fame, even after a runoff vote. On April 23, 1946, the Permanent Committee struck again. In a meeting held on that date in the offices of the New York Yankees, the committee selected 11 more new Hall members. In the words of respected columnist Dan Daniel, the Permanent Committee “announced the baseball beatification of a vast number of worthies” and “decided to load up the Cooperstown pantheon by the wholesale.”4 The BBWAA was not happy that the committee selected Ed Walsh, Joe Tinker, Jack Chesbro, and other stars who played most or all of their careers after 1900.

The Honor Rolls of Baseball

The Permanent Committee made one other decision that has been almost forgotten by history. The committee, which had just elected 11 men to the Hall, also named another 39 individuals to the “Honor Rolls of Baseball.”

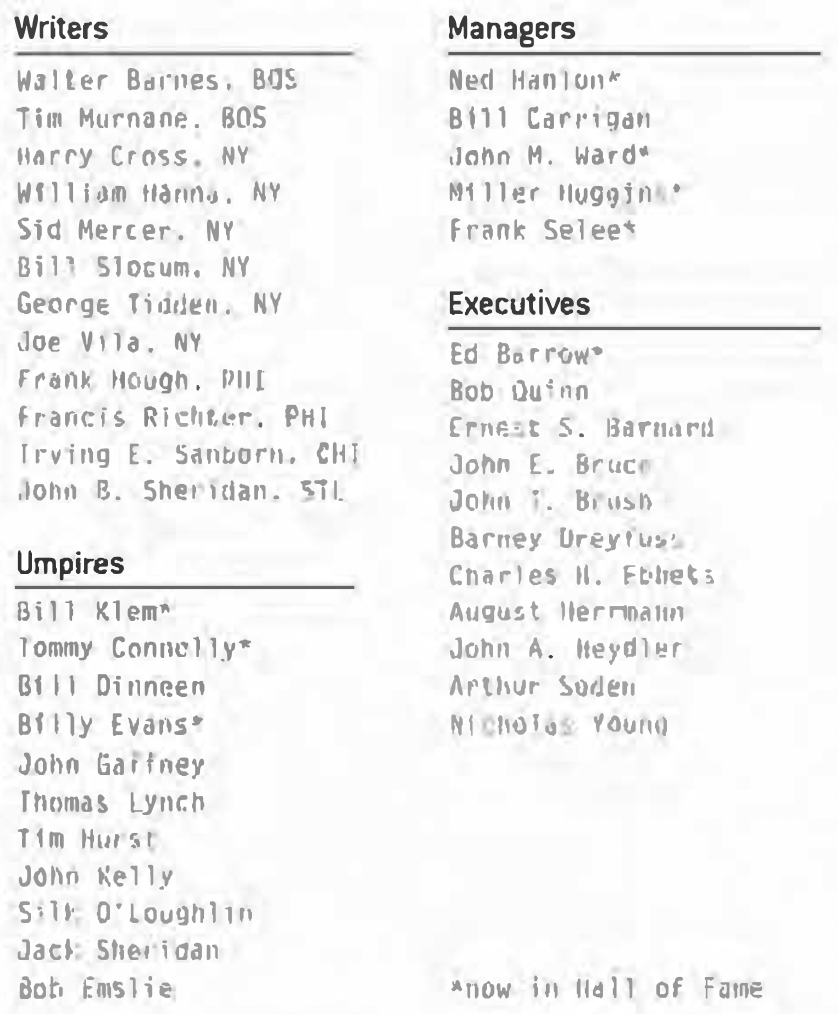

The Honor Rolls consisted of four lists of five managers, 11 umpires, 11 executives, and 12 sportswriters. The Permanent Committee decided, completely on its own, to establish a second level of honor to the Hall of Fame, with the first level – plaques on the wall – being reserved for the outstanding players of the past, along with certain pioneers of the game.

No one had asked the committee to establish this new type of recognition, but since the commissioner had empowered the committee members to act as trustees of the institution, the board acted within the scope of its powers. No one knows who first proposed the idea, but the Honor Rolls of Baseball emerged from the meeting as a fait accompli.

Here is the list of the 39 members of the Honor Rolls:

The Honor Roll recognition was not meant to be a final destination for anyone in these four groups. The committee made it clear that any of the men named to the Honor Rolls would be eligible for full admission to the Hall in the future, “as the pillars of baseball take in their proper alignment in history through the years,” in the words of historian and Hall of Fame director Ken Smith.5

Smith, in the 1974 edition of his book Baseball’s Hall of Fame, offered a possible rationale behind the committee’s selection of 60 men (21 Hall of Fame inductees and 39 Honor Roll members) in 1945 and 1946. The museum itself had recently undergone an expansion, and Smith wrote that the Hall directors “wanted faster action [in creating honorees] for the fine new hall where there was to be room for seventy plaques.”6 Perhaps the committee took it upon itself to create so many new honorees, implied Smith, because before 1945 there were only 27 plaques on the wall and the display room was two-thirds empty.

Reaction to the new designation was swift and almost uniformly negative. The Sporting News devoted an editorial to the Honor Rolls, stating, “Either a man is worthy of the Hall of Fame, or he isn’t. Rigging what might be regarded as an out-and-out expedient to dispose of 39 cases whose claims may have harassed the committee cheapens the entire Cooperstown enterprise.

“There was no demand for a new list of sub-greats. There will never be any cogent reason for that phony type of baseball beatification. If a man was a great umpire or an outstanding writer, he should be elected to the diamond Pantheon, and not placed in an annex of that edifice, so to speak.

“While the failure of the writers to name anybody in their most recent two elections was deplorable,” continued The Sporting News, “it is still more deplorable to load up the Hall of Fame, and to confuse the fan as to who is in the Pantheon and who is in the newly-created Array of Almosts.”7

The Permanent Committee perhaps missed its best chance at gaining support when it failed to select J. G. Taylor Spink of The Sporting News to the Honor Rolls. Spink’s father founded the magazine in 1886 and built it into the “Bible of Baseball,” the most important and widely-read baseball weekly in the nation. Spink became editor and publisher in 1914 and played a major role in uncovering the Black Sox scandal and in popularizing the sport (by distributing the magazine to soldiers in both World Wars). The negative editorial concerning the Honor Rolls, which was published in the magazine on May 2, 1946, suggested that the election process “is in need of a complete overhauling.”8 The editorial did not carry a byline but was likely written by Spink himself.

There was already a certain amount of tension between the Permanent Committee and the BBWAA, stemming from the fact that the committee had unilaterally elected 21 new Hall of Famers due to the failure of the BBWAA to do so in 1945-46. The creation of the Honor Rolls, and the inclusion of sportswriters, merely added to the friction. The committee, in making its selections to the Honor Rolls, did not solicit advice from the BBWAA, preferring instead to decide for itself which writers were most deserving of recognition. The introduction of the Honor Rolls made it appear that no other writers would be joining Henry Chadwick with full Hall membership in the future; instead, deserving writers would be shunted off to the Honor Rolls.

Most of the nation’s sportswriters rejected the Honor Rolls, seeing them as an implied form of second-class membership in the Hall of Fame. ”The baseball writers of America,” said The Sporting News, “insist that there have been shining exemplars of their profession who should be elected to the Hall of Fame, and they insist that the committee has full authority to do so.”9

There were other specific complaints about the Honor Rolls:

- Many people believed that some umpires should have gained election to the Hall as full members, The various committees had not selected any umpires between 1936 and 1946, and many felt that Tommy Connolly and Bill Klem, in particular, deserved full membership. It appears that the Hall of Fame had yet to come to grips with the umpires’ contributions and their relationship to the game.

- The committee honored six writers from New York, but one each from Chicago and St. Louis, and none at all from Detroit, Cleveland, Cincinnati, or other longtime major league cities. Ten of the 12 selected writers came from the eastern seaboard.

- The committee overlooked many deserving writers. One might think that two Chicagoans, Ring Lardner and Hugh Fullerton, would have been among the first selections. None of the Spinks from St. Louis and The Sporting News made it, either, and other ignored writers included Fred Lieb and Grantland Rice.

- Two of the executives on the committee, Ed Barrow and Bob Quinn, named themselves to the Honor Rolls. No matter how deserving they may have been, it always causes controversy when people honor themselves. The committee also named two of its own recently deceased members, Harry Cross and Sid Mercer, while bypassing the eminently qualified Grantland Rice, who replaced Cross on the committee in April 1946.

- Many people questioned why the various committees in the 1930s overlooked Harry Wright, the first baseball manager and the man who, more than anyone else, created professional baseball. Wright managed the undefeated Cincinnati Red Stockings in 1869, won four National Association pennants with Boston from 1872 to 1875, and won two of the first three National League flags in 1877-78. Not only did the committee fail to elect Wright to the Hall of Fame, it also did not put him on the Honor Rolls. Many believed that Harry Wright deserved full Hall of Fame selection as much as John McGraw and Connie Mack, who at the time were the only two Hall of Famers elected mainly as managers.

- Miller Huggins had a fine career as a second baseman from 1904 to 1916, after which he became manager of the New York Yankees. From 1921 to 1928, Huggins led the Yankees to six pennants and three World Series titles. Huggins, who died in 1929, finished third in the 1946 BBWAA balloting, and the men who came in first, second, fourth. fifth. and sixth were all named to the Hall of Fame by the Permanent Committee. Huggins, unexplainably, was relegated to the Honor Rolls. It appears that the Hall had not yet come to grips with the contributions of managers, either.

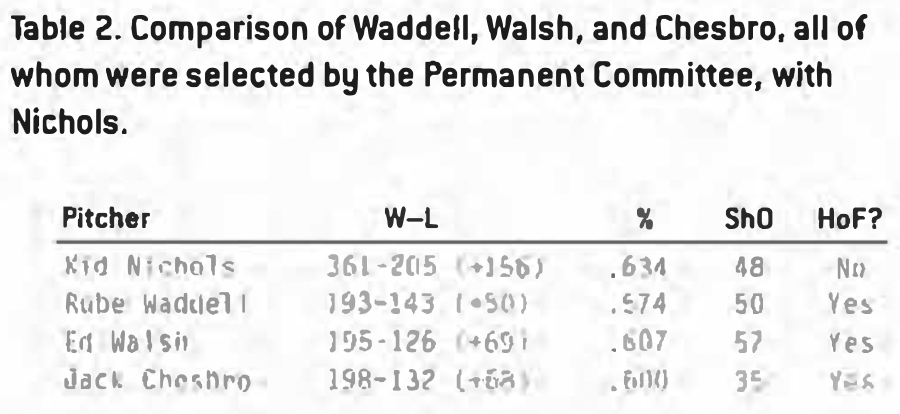

The Permanent Committee, already reeling from the negative reception accorded the Honor Rolls, received a great deal of criticism for its choices of 11 players to full Hall membership at that same 1946 meeting. The committee enshrined three pitchers (Ed Walsh, Jack Chesbro, and Rube Waddell) who did not win 200 major league games, while passing over 300-game winners Tim Keefe, John Clarkson, Pud Galvin, Mickey Welch, and Kid Nichols. The comparison of Nichols to Chesbro, Walsh, and Waddell is especially illuminating.10

Nichols, though he played in the major leagues at an earlier date than the other three, was still living in 1946, This makes the failure of his candidacy unusual, since Hall of Fame voting committees have often shown a preference for candidates who are still alive and able to enjoy the honor.

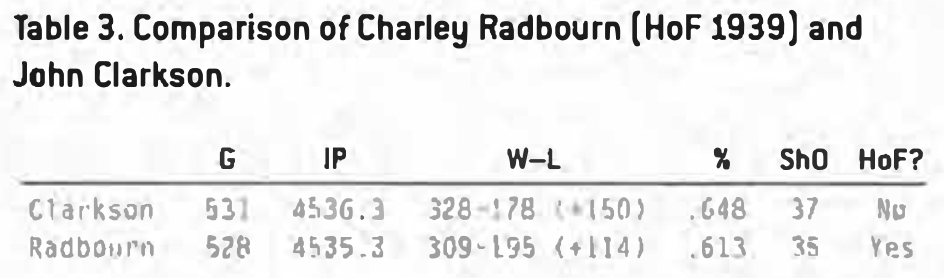

In addition, the previous committee had selected Charley (Old Hoss) Radbourn to the Hall in 1939 but ignored John Clarkson, a pitcher from the same era with almost identical credentials. The Permanent Committee also bypassed Clarkson when it selected 21 other players to the Hall in 1945 and 1946.

Clarkson, who won 19 more games than Radbourn and lost 17 fewer, did not receive a plaque in Cooperstown until 1963.

These and other inconsistencies in the Permanent Committee’s selection process contributed to the lack of acceptance of the Honor Roll concept. Because the committee had made several highly criticized Hall of Fame choices in 1946, columnists and commentators across the nation considered the Honor Rolls to be not much of an honor. The committee had lowered the standards of the Hall of Fame with some of its more questionable selections, which made the Honor Rolls appear even less of an honor than they were intended to be. The Sporting News led the critical charge, calling the Honor Roll selections “mere appendages to the star wagon” and suggesting that the Rolls were a “convenient depository” for borderline Hall candidates.11

The Hall of Fame held an induction ceremony on June 13, 1946, to unveil the plaque of Commissioner Kenesaw M. Landis, who died in November 1944 and was elected to the Hall of Fame one month later. The ceremony for the 11 old-time players elected by the Permanent Committee in April 1946 and the four modern players selected by the BBWAA in 1947 was held in Cooperstown on July 21, 1947. Eight of the 15 men were still living at the time, but only the 66-year-old Ed Walsh appeared at the ceremony and received his plaque.12

As for the Honor Rolls, no transcript of the 1946 ceremony or the 1947 ceremony exists, and Hall of Fame archivists do not know if the 39 honorees were mentioned on either date. The New York Times did not mention the Honor Rolls or the 39 men named to the Rolls, and do not indicate that the Honor Rolls played a part in the proceedings at either ceremony. The archives of the Hall also contain no evidence that any formal Honor Rolls were ever displayed at the Cooperstown museum, and it appears that the Rolls themselves never took physical form.

After the hail of criticism subsided, the Honor Roll concept utterly disappeared from public view. Ken Smith’s book, Baseball’s Hall of Fame, devoted a whole chapter to the Honor Rolls of Baseball in its 1947 edition, but when the book was reissued several times in subsequent years the Honor Rolls were dismissed in one paragraph. Smith, in the 1974 edition of the book, listed the 39 honorees, but wrote, “the committee found itself in a hopelessly large field and there were never any additions to the original thirty-four [sic].”13

The Honor Rolls were quickly forgotten in the following years, and died a lonely death as the Permanent Committee, which had inducted 21 players and 39 Honor Roll recipients in a span of only 13 months, went into hibernation for the next three years. In 1949, the committee met again and inducted two deserving pitchers, Mordecai (Three-Finger) Brown, another beneficiary of the “death effect,” and the previously ignored Kid Nichols, who was fortunately still alive at the time. The committee members added no new names to the Honor Rolls, and no mention of the Rolls can be found in the newspapers or in The Sporting News. When umpire Bill Klem died in September 1951, no mention of the Honor Rolls was made in his obituary in The New York Times, although Klem had won the honor only five years earlier.14

In 1953, the Permanent Committee split into two groups. The trustee function of the committee passed to the Board of Trustees, and the election function became the province of a new 11-man Veterans Committee. This panel met on September 28, 1953, in the offices of Commissioner Ford Frick, and in less than one hour it elected six men to the Hall of Fame. Three of the new inductees – umpires Bill Klem and Tommy Connolly, and executive Ed Barrow – were promoted from the Honor Rolls, though none of the newspaper reports at the time mentioned that fact. A fourth inductee was the long-overlooked Harry Wright. In future years, four of the five managers on the Honor Rolls have been elected to the Hall, as well as an additional umpire (Billy Evans), but news reports of their selections to the Hall of Fame made no mention of their past Honor Roll status.

The Veterans Committee did not address the issue of sportswriters and their place in the Hall of Fame at any time during the 1950s. With the Honor Rolls almost totally forgotten, the writers remained outside of Cooperstown until the early 1960s, with the establishment of a new honor for writers. Significantly, the recognition was (and still is) bestowed not by the Veterans Committee, but by a vote of the BBWAA itself.

The writers finally gained recognition in 1962 with the introduction of the J. G. Taylor Spink Award, given “for meritorious contributions to baseball writing.” This is what is often referred to as the “writers’ wing” of the Hall, although the so-called “wing” is actually a single plaque, listing all the recipients, as part of a display in the museum library. Spink himself was the first recipient, followed by Ring Lardner in 1963 and Hugh Fullerton in 1964. All three of these men had been passed over by the Honor Rolls.15 To date, the only Honor Roll writers to win the Spink Award have been Sid Mercer (1969) and Tim Murnane (1978). However, the Hall of Fame regards the honored writers as a separate entity. The Hall of Fame web site clearly states that the Spink Award winners are “honorees,” not “inductees,” a word they reserve for full members of the Hall. 16

Conclusion

Despite the criticism – much of it deserved – of the Honor Rolls of Baseball, the concept might have been a successful one if it had been implemented differently. The idea of a second level of honor for the Hall of Fame is a worthy one, although it is probably too late to attempt at this time, more than 65 years after the Hall first opened its doors in 1939.

Unfortunately, the idea for the Honor Rolls came too late. From 1937 to 1946 the Permanent Committee and its predecessors made several selections to the Hall of Fame that would have fit much better on an Honor Roll than with a plaque on the wall implying that the individual was the equal of a Babe Ruth. Roger Bresnahan, elected to the Hall by the Permanent Committee in 1945, played an important role in defining the catching position and in developing catching equipment. If the Honor Rolls had been instituted before 1945, perhaps his contributions would have been more appropriately recognized on an Honor Roll of contributors to the game. The same might be said of Candy Cummings, elected in 1939 mostly for inventing the curveball, Tommy McCarthy, selected in 1946 for contributions to strategy, and the previously mentioned Morgan Bulkeley.

By the time the Honor Roll emerged from the 1946 committee meeting, the Hall had already established a lower level of accomplishment as a qualification for enshrinement. In putting plaques on the wall for such lesser lights as Bresnahan, Bulkeley, McCarthy, and others, the Hall had created what Bill James has called “a second tier of Hall of Famers who stretched the definition of greatness so far that any reasonable version of equity could never be achieved without honoring hundreds and hundreds of players.” The Honor Rolls, then, appeared to many as an even more inferior level of honor, lower than the previous Hall selections had established up to that point. It made the Honor Rolls look like an unwanted “Array of Almosts” who didn’t quite measure up to the real Hall inductees, questionable as some of them might be.

The concept might have proved successful if the trustees of the Hall of Fame had created a scheme for the Honor Rolls before the first election in January 1936. Hand-in-hand with a concerted effort to identify the game’s greatest players and contributors, the two-level system of recognition might have worked.

DAVID L. FLEITZ is a from Bowling Green, Ohio. He is the author of Shoeless: The Life and Times of Joe Jackson, Louis Sockalexis: The First Cleveland Indian, and Ghosts in the Gallery at Cooperstown. His latest book, Cap Anson, The Grand Old Man of Baseball, was published by McFarland in 2005.

MEMBERS OF THE HONOR ROLLS

Writers

Tim Murnane was an Irishman who played in the National Association from 1871 to 1875 and in the National League from 1876 to 1878; he stole the first base in NL history in 1876. He also played for and managed the Boston Union Association club in 1884, then became a sportswriter. He wrote for the Boston Globe from 1887 till his death in 1917. He liked to put humor in his writing; he once wrote, “Pitcher [Harley] Payne contorts himself into the Chinese laundry symbol for 33 cents before the delivery of the ball.” Some say that Murnane virtually invented the modern baseball newspaper column.

Francis Richter founded Sporting Life in Philadelphia in 1883, three years before The Sporting News opened for business in St. Louis. Richter was also instrumental in the return of the National League to Philadelphia that same year. Richter criticized the NL monopoly on baseball and supported the Players Association in 1890. He was so independent that during World War I, Major League Baseball gave financial assistance to The Sporting News, but refused to do the same for Sporting Life, which ceased publication shortly afterward.

Bill Slocum was one of the first writers to appear regularly on radio, and Harry Cross, president of the New York chapter of the BBWAA, served on the Permanent Committee before he died three weeks before the 1946 election. William Hanna received credit for bringing a literary quality to baseball writing.

Irving E. Sanborn, of the Chicago Tribune, exposed the story of ballplayers avoiding the military draft and accepting money for easy work in shipyards and defense plants during World War I. Sid Mercer was a longtime writer for the New York Journal and the later Journal-American, involved in many controversies with John McGraw. The Player of the Year award, given annually by the New York chapter of the BBWAA, is still called the Sid Mercer Memorial Award. Joe Vila, of the Brooklyn Eagle and the New York Sun, was the first writer to use a typewriter at ringside of a prizefight. He also created the football play-by-play story in the late 1880s.

George Tidden (New York), Frank Hough (Philadelphia), John B. Sheridan (St. Louis), and Walter Barnes (Boston) were all influential early sportswriters in their respective cities.

Managers

Frank Selee and Ned Hanlon managed all 10 NL pennant winners in the 1891-1900 decade, each winning five. Hanlon built the famous Baltimore Orioles team that won the flag from 1894 to 1896, then moved to Brooklyn and won in 1899 and 1900. Selee built two great teams, managing the Boston Beaneaters from 1890 to 1901 and then moving to the Chicago Cubs. He stepped down as Cubs manager in 1905 due to illness, just before Frank Chance led the club to four pennants in five seasons.

Bill Carrigan caught for the Boston Red Sox and managed the team from 1913 to 1916, winning World Series titles in 1915 and 1916. Carrigan introduced Babe Ruth to the majors, and Ruth said in his autobiography that Carrigan was the greatest manager he ever had. Carrigan then went into the banking business and returned as Red Sox manager from 1927 to 1930.

John Montgomery Ward threw a perfect game as a pitcher, then moved to shortstop when his arm gave out. He captained the New York Giants to pennants in 1888 and 1889, and founded the short-lived Players League in 1890.

Miller Huggins, a former National League infielder, won six pennants and three World Series titles with the New York Yankees in the 1920s.

Executives

Ed Barrow was the president of the Paterson, NJ, minor league club when he discovered Honus Wagner and sold him to the Louisville National League team in 1897. Barrow managed the Detroit Tigers, served as president of the International League, then succeeded Carrigan as Red Sox manager and won the 1918 World Series. He then became business manager of the Yankees and built that team into a dynasty.

Nicholas Young was known to all as “Uncle Nick” during his term as National League president from 1885 to 1903. He did his best to stay out of controversies, preferring instead to make flowery public pronouncements and busy himself with league statistics. Young, who became the league’s first secretary in 1876, sometimes added hits to pad the averages of favorite players like Cap Anson, and for that reason the individual player statistics from the 1870s through the 1890s don’t always add up to the league totals evenly.

Arthur Soden owned the Boston National League club from 1877 to 1906, while Barney Dreyfuss owned the Pittsburgh Pirates from 1900 to 1931 and August Herrmann ran the Cincinnati Reds from 1902 to 1927. John E. Bruce served as secretary of the National Commission when Herrmann chaired that body in the early 1900s. Charles H. Ebbets owned the Brooklyn Dodgers from 1898 to 1925 and built Ebbets Field, while J. A. Robert (Bob) Quinn was president and general manager of the Red Sox, Dodgers, and Braves.

Ernest S. Barnard was the second president of the American League (1927-1931), and John A. Heydler was president of the National (1918-1934).

John T. Brush, as primary owner of the Cincinnati Reds (1890-1902) and New York Giants (1902-1912), played a major role in the war between the leagues of 1901-1903. He refused to let his Giants play a post-season series against the American League champion in 1904, but Brush reversed course in 1905 and helped create the modern World Series.

Umpires

Tim Hurst was one of the most colorful umpires. He used an aggressive style and rough language to keep order on the field, and battled many players, managers, and even fans. His career as an umpire ended in 1909 when he spit on and spiked Philadelphia Athletics second baseman Eddie Collins. Hurst explained, “I don’t like college boys.”

Bill Klem umpired in the National League for 36 seasons, appearing in a record 18 World Series, and Tommy Connolly served for four years in the National League and 31 in the American. Connolly umpired the first game in American League history on April 24, 1901, at Chicago. Both men gained election to the Hall of Fame in 1953.

Bill Dinneen was a fine pitcher, winning 170 major league games and three more in the 1903 World Series, before he turned to umpiring. Honest John Gaffney and Honest John Kelly were the two leading umpires of the 19th century, while Thomas Lynch gave up his umpiring duties to become president of the National League from 1910 to 1913. Billy Evans was a great umpire, baseball’s first general manager (for Cleveland in 1928), and the author of a widely read book on baseball rules called Knotty Problems.

Bob Emslie was an umpire for more than 30 years, best remembered for officiating the 1908 “Merkle’s Boner” game between the Giants and Cubs. Jack Sheridan was an outstanding umpire who worked in four World Series from 1905 to 1910, and Silk O’Loughlin was famous for his bellowing “Strike Tuh” call.

Sources

Carter, Craig, ed., Daguerreotypes, 8th Edition (St. Louis: The Sporting News Publishing Co., 1990).

Ivor-Campbell, Frederick, with Tiemann, Robert L., and Rucker, Mark, eds., Baseball’s First Stars (Cleveland: SABR, 1996).

James, Bill, The Politics of Glory: How Baseball’s Hall of Fame Really Works (New York: Macmillan, 1994).

Smith, Ken, Baseball’s Hall of Fame (New York: Grosset and Dunlap, 1947, 1974).

Spink, J.G. Taylor, ed., The Sporting News Official Baseball Guide and Record Book (St. Louis: The Sporting News Publishing Co., 1955).

Turkin, Hy, and Thompson, S.C., The Official Encyclopedia of Baseball, Revised Edition (New York: A.S. Barnes and Co., 1955).

Vlasich, James A. A Legend for the Legendary: The Origin of the Baseball Hall of Fame (Bowling Green, Ohio: Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1990).

Notes

1. The Honor Rolls were sometimes called the Honor Roll, implying that each of the four classes of honorees existed on the same roll. Ken Smith, in his book Baseball’s Hall of Fame (1947), used the term Honor Rolls or Rolls of Honor. The New York Times (April 24, 1946) employed the term Honor Rolls, but the 1947 Sporting News Official Baseball Guide and Record Book used the singular form, as did the weekly Sporting News itself.

2. Vlasich, James A. A Legend for the Legendary: The Origin of the Baseball Hall of Fame (Bowling Green, Ohio: Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1990): 49-50.

3. Some sources state that the committee selected 10 old-timers at the suggestion of Commissioner Landis, who had foreseen a possible stalemate in the upcoming 1945 BBWAA voting.

4. James, Bill, The Politics of Glory: How Baseball’s Hall of Fame Really Works (New York: Macmillan, 1994): 44.

5. Smith, Ken, Baseball’s Hall of Fame (New York: Grosset and Dunlap, 1947): 213.

6. Smith, Baseball’s Hall of Fame (1974 edition): 64.

7. The Sporting News, May 2, 1946.

8. The Sporting News, May 2, 1946.

9. The Sporting News, May 2, 1946.

10. Statistics in this article come from Baseball-Reference.com.

11. The Sporting News, May 2, 1946.

12. New York Times, July 22, 1947.

13. Smith, Baseball’s Hall of Fame (1974 edition): 71.

14. New York Times, September 17, 1951.

15. The next three Spink Award winners — Charles Dryden (1965), Grantland Rice (1966), and Damon Runyon (1967) — had also been overlooked for Honor Roll recognition in 1946.

16. For a list of Spink Award winners, see the Hall of Fame website at baseballhalloffame.org.

17. James, The Politics of Glory, 157.