Jim Brosnan’s The Long Season

This article was written by Greg Erion

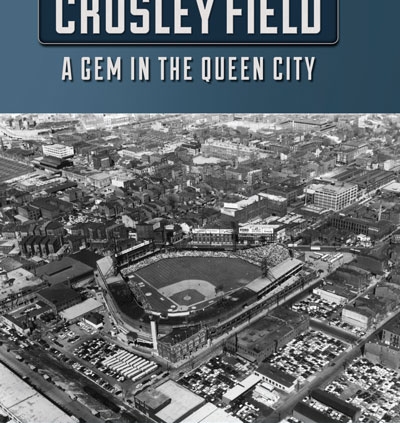

This article was published in Crosley Field essays

In Mark Armour’s SABR biography of Jim Brosnan he observes that Brosnan “wrote the first honest portrayal of the life of a ballplayer,” and that “Fifty years on, Brosnan’s books (The Long Season and The Pennant Race) remain the gold standard for baseball memoirs.” Brosnan allowed fans to gain a degree of understanding about the daily life of major leaguers, leading to even more candid books on their lifestyle such as found in Jim Bouton’s Ball Four. As Armour noted, “Brosnan’s intellect and writing ability were a revelation at a time when readers had been served vanilla depictions of their baseball heroes performing glorious deeds on the fields of battle. Brosnan drew himself and his teammates as complicated humans struggling to make their way.”1

In Mark Armour’s SABR biography of Jim Brosnan he observes that Brosnan “wrote the first honest portrayal of the life of a ballplayer,” and that “Fifty years on, Brosnan’s books (The Long Season and The Pennant Race) remain the gold standard for baseball memoirs.” Brosnan allowed fans to gain a degree of understanding about the daily life of major leaguers, leading to even more candid books on their lifestyle such as found in Jim Bouton’s Ball Four. As Armour noted, “Brosnan’s intellect and writing ability were a revelation at a time when readers had been served vanilla depictions of their baseball heroes performing glorious deeds on the fields of battle. Brosnan drew himself and his teammates as complicated humans struggling to make their way.”1

The impact of what Brosnan accomplished through his writing has been lost over the passage of time. Modern readers accustomed to blogs, Facebook, reality shows, and the like might have difficulty relating to how sporting events and players were presented to the public well into the twentieth century.

For most baseball fans in the mid-1950s the ability to gain an understanding of the inner workings of the game was quite restricted. Box scores recorded events but offered little in the way of underlying player perspectives. Accounts of games or players in the sports sections of newspapers, magazine articles, and occasional player biographies tended toward the bland, superficial, or worshipful. This commonality of theme was reinforced by the fact that frequently writers specializing in one of these mediums frequently wrote for all of them. If a baseball player (or most any sports figure for that matter) shared his life story or offered commentary, it most often came about in a ghost-written effort or reflected the expertise of a professional writer.

A case in point is found in the first serious publication on the life of Stan Musial, appearing in 1964, a year after his playing career ended. Titled Stan Musial: “The Man’s” Own Story, it contained the telling tag line “As told to Bob Broeg.”2 Broeg essentially wrote a book more or less reflecting the same adoring perspective he offered in years of covering Musial’s career while a regular contributor to The Sporting News. It was the traditional narrative of an underprivileged youth struggling to make good, deferential in nature, tracing Musial’s career but from a distance, never approaching a sense of intimacy.

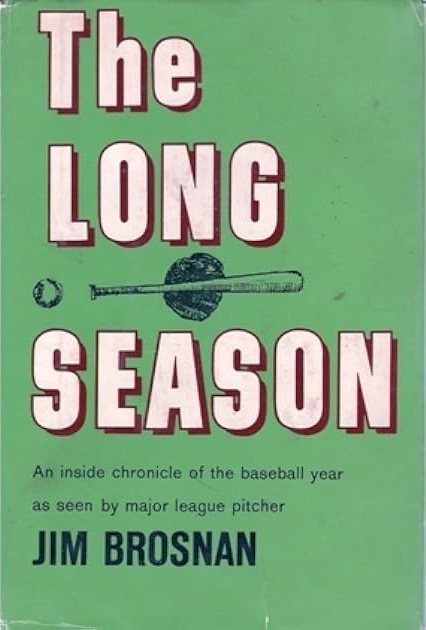

These types of literary efforts revealed little beyond antiseptic numbers or milestone achievements. This sterile approach to chronicling baseball and sports in general began to change in the early 1960s as a tone of realism emerged. One agent of transformation came with publication of The Long Season in 1960, which chronicled the experiences of a journeyman pitcher during a season with a mediocre team. It was not ghost-written or “as told to”; it contained the honest feelings of pitcher Jim Brosnan’s struggle to survive in a fiercely competitive environment.

How Brosnan’s effort, in a diary format contrasted with then-followed sportswriting axioms could be illustrated by comparing his entries with those of newspaper reporting on any given game he described. A case in point can be shown by comparing news coverage of his inaugural pitching effort for the Cincinnati Reds at Crosley Field with how he described the same game in The Long Season. The contest, played on June 24, 1959, was important to Brosnan. He had been traded to the Reds just a few weeks before; he needed to look good before the hometown crowd.

The July 1, 1959, issue of The Sporting News contained a box score for the match, between Cincinnati and the Chicago Cubs. The final score shows a 5-0 win for Cincinnati. Brosnan, did well, throwing a complete-game shutout, allowing the Cubs just four singles and two walks while striking out seven batters. His opponent, Dick Drott, by way of contrast, did not last out the first inning. Drott gave up three hits, a walk, and four runs before being removed from the game.

Frank Robinson got three hits, one a double. Ed Bailey and Gus Bell drove in two runs apiece, Bailey on his fifth home run of the year. The game lasted 2 hours, 14 minutes and was played before 6,510 fans. The Sporting News’s brief explanation of the game and box score recounted these details as well as the fact that Brosnan had completed his first game since September 1, 1956, when he was with the Cubs.3

The Chicago Tribune’s coverage of its home team had a more extended account of the contest, explaining various plays as well as offering a brief aside on Brosnan having formerly pitched for the Cubs and noting his recent trade to the Reds from St. Louis.4 Nothing in either of these articles from the player’s perspective was shared; it was typical of the times. These separate reports of the game pretty much summed up what fans came to expect in the way of information on major-league baseball.

After the season ended, however, with publication of The Long Season, a much different rendering and decidedly untraditional perspective of baseball emerged on the June 24 game. His entry for June 24 was but one of a series of penned by Brosnan spanning spring training through the last day of the season.

Recollections of the contest commenced with off-field concerns for family dynamics:

“How many tickets do you want?” I (Brosnan) said into the phone. … That’s lotta box seats. … I guess I can get ’em. The way we been going I don’t think we’re gonna pack Crosley Field. … Mom coming with you tonight?… She’s never seen me pitch at a major league park, has she? …”5

Even though this was Brosnan’s first appearance as a Red at Crosley Field, the pressure of performing well before his new teammates at home was momentarily supplanted by the need for tickets to the game.

Once out on the field, Brosnan’s challenge of coming up with tickets was overtaken by a new concern; a blister on the third finger of his pitching hand had popped while he warmed up. Reds manager Mayo Smith asked if Brosnan could make it. Offering the customary bravado of an athlete, Brosnan reassured Smith, “I’ll give it a try. It bothers my breaking stuff mostly. I’ll lay off the curve and use my slider.”6

The game commenced inauspiciously for Brosnan. A hit and a walk, just one out, and Brosnan found himself facing Cubs shortstop Ernie Banks who just happened to have 67 RBIs, the most in the majors.7 With the game at a crucial point in the top of the first, what was Brosnan thinking? Not what casual observers of the game might think. A mental soliloquy commenced on the mound.

“Wonder if Mother is here, yet.” Then almost as an afterthought, “I can’t take a chance throwing Banks a breaking ball away and down. That’s a good double-play pitch but if I make a slight mistake I’m behind three runs.”

Brosnan ruminates on catcher Ed Bailey’s call to throw a slider. “Bailey must like my slide ball. (Most of the pitcher’s control on breaking balls lies in his fingers. I had a bad finger. I must have poor breaking stuff. Q.E.D. Well, Bailey probably never heard of Q.E.D., so why not give him what he wants?)”8 Brosnan might have been the only major-league ballplayer to have expressed doubt in Latin when deciding on what pitch to throw.

His mother, pitch selection, the state of his finger, and a Latin phrase. All these pass through his mind while one of the most dangerous hitters in the game waits at the plate.

Brosnan throws a slider, Banks pops out to Bailey, and after the next batter lines to left, Brosnan has survived the first inning. All outs were made on sliders.

Reds manager Mayo Smith greets him in the dugout. “That’s your bad inning, Jimmy. Your fast ball’s alive.” Brosnan says to himself, “I’d only thrown one (fastball).” With that terse four-word passage, Brosnan shared his estimation of Smith’s powers of perception and by extension, his confidence in Smith’s management capabilities.9

All these mental gyrations and it was only the first inning. Brosnan’s commentary on the game, while involving a few key plays, did not focus on pitching strategy or the overall game but on his finger. It was bleeding. The following innings dealt with the challenge to minimize bleeding.

“Doc (Doc Anderson, the team’s trainer), let’s go to work. This finger’s bleeding. You got any collodion we can put on it?”10 Anderson goes in to action. “This’ll do the trick, my boy. Just let old Doc take care of your finger. You take care of the batters.” Anderson kept medicating the finger each inning but it quickly wore off, leaving specks of blood on the ball.

As the game went on, Brosnan developed a rhythm. “But for the most part my arm worked like a well oiled machine. The batter came to the plate. My experience classified him. My mind told my arm what to do. And it did it. It seldom happens precisely that way.”11

So it went the rest of the way until Cubs batter Dale Long came to the plate with two outs in the ninth. Brosnan, the bleeding momentarily under control, was now into the mental game. “Why not experiment a little? Think I’ll throw him a change-of-pace. Defy the book.” Long grounded to first and Brosnan had a shutout. Robinson made the final out at first and stuck the ball into his back pocket. “Oh no, Robby,” I said. “That one’s mine.”12

Brosnan’s shutout involved an almost meaningless contest between two teams going nowhere. Chicago was then in fifth place; Cincinnati in seventh. This rather mundane contest did not concern a turning point in their respective fortunes as the two teams ended the year tied for fifth in the eight-team National League.

It was but one game yet his thoughts, ranging from questioning his pitches to the Q.E.D. reference to being a “well oiled machine,” were in microcosm a reflection on the roller-coaster ride his confidence took all year long.

Brosnan’s experiences during this game were totally foreign to what the larger body of fans had come to expect in understanding the game. At its core, while sharing numerous experiences and touching on many themes, The Long Season resonated with readers because it tapped into something all have felt at one time or another: a crisis of confidence. It went beyond the bravado conventionally shared on sports pages, in baseball books, or in magazines. Players fall into slumps, are sent to the minors or released. The Long Season observes baseball immortal Stan Musial experiencing his first sub-.300 season. Reds teammate Frank Thomas, one of the more prolific hitters in 1958, endures a yearlong slump. Marv Grissom and Sal Maglie, two veteran pitchers with 20 years’ experience between them, find they can no longer perform; their careers end. Uncertainty is always a presence.

For Brosnan particularly, his midyear trade from St. Louis to Cincinnati, jarred belief in himself. It affected his family, a consideration beyond the public’s consciousness. His wife, Anne, hearing he has been traded from the Cardinals, cries, “Oh no! Oh God … not that. I’ll never be able to drive from Chicago to Cincinnati.” She then asks, “Who did they trade you for?” Brosnan replies, “Jeffcoat. Straight swap I guess.” “Jeffcoat!” Anne responds, “Couldn’t they get more for you than that? Oh honey, they just wanted to get rid of you.”13

In clearing up loose ends with the Cardinals, he met with general manager Bing Devine and asked why he was traded to the Reds. Devine responded, “Solly (Hemus, manager of the Cardinals) has said that he just doesn’t seem to be able to get the work out of you.”14 Hemus’s perspective on Brosnan’s ability disturbs him. Over a month later Brosnan in talking with Reds bullpen coach Clyde King speaks of this. “Hemus didn’t like me. I didn’t like him. But I’ve been thinking. With the Cardinals, I was beginning to lose confidence in my pitching ability, and over here (with the Reds) I’ve proved that I can do just as good a job as ever. So my guilt feelings about Hemus must have had a direct effect on my pitching.”15

Part of what helped Brosnan gain confidence came with Fred Hutchinson’s replacement of Mayo Smith as manager. He helped guide Brosnan through the metamorphosis from starter to relief pitcher.

Brosnan’s shutout of the Cubs was an aberration. It was the seventh complete game in what were then 38 career starts. He never pitched a complete game again.

After another start in which he was pulled earlier than he thought proper, Brosnan confronted Hutchinson. Feeling he was somewhat less than a complete pitcher based on a dismal record of finishing games, Brosnan was set right by his manager, who recognized the true value of his talent. “You don’t think you were pitching good ball up till then, do you? I didn’t. You’ve got good stuff and you’re a pretty good pitcher. I may use you in the bullpen now because I know that you can do that job for me. Not every pitcher can. As for you, don’t worry about it. You’ll get plenty of work.”16

Hutchinson was right. Brosnan could do the job coming out of the bullpen, a fact proved over the next few seasons. But those days were in the future.

How Brosnan dealt with the trade, pitching triumphs such as his effort on June 24, or games where his effort made for an early exit, proved the essence of his book. His everyday struggles connected with followers of the game. And made The Long Season one of the most popular pieces of baseball writing.

GREG ERION died in December 2017 after a brief illness. He retired from the railroad industry and taught history part-time at Skyline Community College in San Bruno, California. He wrote several biographies and game articles for SABR. Greg was one of the leaders of SABR’s Baseball Games Project. With his wife, Barbara, he was a resident of South San Francisco, California.

Notes

1 Mark Armour, “Jim Brosnan,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/b15e9d74.

2 Bob Broeg, Stan Musial: “The Man’s” Own Story as Told to Bob Broeg (New York: Doubleday, 1964).

3 “National League,” The Sporting News, July 1, 1959: 26.

4 Edward Prell, “4 Run Salvo Routs Drott in 1st Inning,” Chicago Tribune, June 25, 1959: D1. Brosnan was traded from the St. Louis Cardinals to Cincinnati on June 8, 1959.

5 Jim Brosnan, The Long Season (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1960), 183.

6 Brosnan, The Long Season, 184.

7 Banks would end the season hitting .304 with 45 home runs and 143 RBIs, the most in the majors. His performance won him a second consecutive Most Valuable Player award.

8 Q.E.D. A Latin term, quod erat demonstrandum essentially translates to “which was to be proved.” https://macmillandictionary.com/us/dictionary/american/q-e-d.

9 Less than two weeks later, Smith was fired and replaced by Fred Hutchinson.

10 Collodion is a clear, syrupy liquid compound used to close small wounds and cuts.

11 Brosnan, The Long Season, 186.

12 Brosnan, The Pennant Race (New York: Harper, 1962), 184-187, covers the June 24 game.

13 Brosnan, The Long Season, 160. Hal Jeffcoat’s major-league career lasted just 12 more games.

14 Brosnan, The Long Season, 171.

15 Brosnan, The Long Season, 206-207.

16 Brosnan, The Long Season, 210.