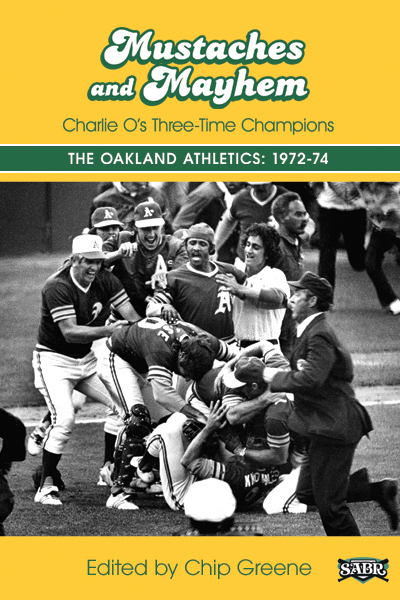

1972 Oakland A’s: Junkyard Dogs

This article was written by Ted Leavengood

This article was published in 1972-74 Oakland Athletics essays

In his autobiography, Reggie Jackson said that the championship Oakland Athletics “were the meanest junkyard dogs who ever played the game.”1 He believed that Charlie Finley’s legendary cheapness, which confronted them at every turn, made them tough and hungry. “We were like a pickup team from the baseball ghetto and nobody wanted to come into our neighborhood and play,” Jackson said. “We were always mad at Charlie because we were the best baseball team in the world and we knew he was paying us slave wages.”2

In his autobiography, Reggie Jackson said that the championship Oakland Athletics “were the meanest junkyard dogs who ever played the game.”1 He believed that Charlie Finley’s legendary cheapness, which confronted them at every turn, made them tough and hungry. “We were like a pickup team from the baseball ghetto and nobody wanted to come into our neighborhood and play,” Jackson said. “We were always mad at Charlie because we were the best baseball team in the world and we knew he was paying us slave wages.”2

Whatever the source of the anger, the Oakland Athletics were a fighting and feuding bunch. The index to Dayn Perry’s biography of Jackson has a listing for “fights (fighting)” with six references that only begin to detail the many memorable confrontations, some of which included Reggie, though he was hardly a lone actor.3 The first reference leads the reader to a confrontation between Jackson and reliever Dick Woodson of the Minnesota Twins in 1969 when Billy Martin – legendary for his own brawling behavior – was the Twins’ rookie manager. As a very successful college football player, Jackson believed he played the game with a higher level of intensity than many, and so when he charged Woodson after the pitcher threw at him, he proudly said he executed a “form tackle that would have made Frank Kush (legendary Arizona State coach) proud.”4

From the perspective of the modern game, it is difficult to recall fully the way the game was once played by rough-and-tumble personalities like Billy Martin. Before free agency opened the financial floodgates and players started getting paid like movie stars, tough guys like Martin and Jackson were less concerned that needless injury from fighting might cut into their seven-figure paydays. Back in the day – pre-1975 – when teams poured onto the field after a beaning, the odds that a punch would be thrown were far greater, and one of the last great teams celebrated for their pugilism almost as much as their baseball talent was the Oakland Athletics. And their anger found a home at least as often in their own clubhouse as it did on the field against the opposing team.

The press gave internal strife within the Oakland clubhouse a prominent role in crafting the competitive edge of the Oakland Athletics, or at least were complicit in airing the private squabbles publicly. Wells Twombly of The Sporting News wrote about the rivalry between Billy North and Angel Mangual under the heading, “Civil Strife Brings Out Best in A’s.” Mangual and North literally fought for playing time in center field during the ’73 midseason, but the more pugnacious of the two, Billy North, won the job by TKO. Sal Bando, captain of the team and chairman of the “morale committee,” told Twombley that total candor in the clubhouse “is a tradition with us. … The owner screams at the players. The manager screams at the players and the players scream right back.”5

Jackson was the most notorious of a wild bunch and his remarks about fights within the clubhouse provide much of the available information on them. However, the other protagonists have invariably clarified key points in the Jackson narrative. Jackson’s reputation took off during the first championship season in May 1972 when he and Mike Epstein had one of the more serious confrontations of any that ensued.

Jackson had been anchored the defensive backfield at Arizona State and Mike Epstein had played fullback for the University of California Golden Bears before turning to baseball. Epstein was a big, burly man whose 230 pounds were stretched over a 6-foot-3 frame and he was used to hitting the line with enough brute force to gain his three yards in a cloud of dust. Charlie Finley gave Jackson authority over distributing the tickets given to players for each game that were then doled out to family and friends. Epstein – whose family lived in the Bay Area – asked for tickets in late May and Jackson asked who the tickets were going to. “It’s none of your business,” Epstein shot back.6 According to Epstein, the fight was a short one as the fullback knocked the defensive back unconscious.7

Besides the two footballers, the A’s boasted two diminutive players with quick tempers. Cuban-born Bert Campaneris stood only 5-feet-10 and was known for having a short fuse.8 In the American League Championship Series against the Detroit Tigers, the A’s were once more up against manager Billy Martin. In Game Two of the series, Campaneris had gone 3-for-3 and Martin ordered his pitcher, Lerrin LaGrow, to throw at Campaneris. When the ensuing pitch hit the feisty Cuban in the ankle, he got up and whipsawed his bat toward the mound where the helicoptering projectile “narrowly missed the top of his head.”9 The benches emptied and though few punches were actually thrown, Martin was physically removed from the field of play screaming at Campaneris to come out and fight him. The Oakland players remained uncharacteristically placid in response, but Campaneris was fined $500 and suspended for the rest of the ALCS.

The other player in the Oakland clubhouse whose small size hid a large fist was Billy North, who led off for Oakland during his six-year tenure with the A’s. He fought numerous times with opposing pitchers. Reggie Jackson described and incident in which North charged the mound after Doug Bird of the Kansas City Royals threw him a strike. The pitch seemed to have no special message attached to it, but according to Jackson, Bird had beaned him three years earlier and North had not forgiven the offense until that very moment when he “walked to the mound and dropped Bird with a right to the jaw and then just started banging away on him.”10

As Jackson put it, “It was always something.”11 Reggie recounted fights between Rollie Fingers and Blue Moon Odom, Bert Campaneris, and Vida Blue. There was the time that “Blue Moon Odom went after reserve outfielder Tommy Reynolds with a coke bottle.”12 But the worst of them all may have been the numerous accounts of the fight between Billy North and Reggie Jackson.

The confrontation is said to have occurred in the shower, where the slippery conditions contributed to the injuries suffered by Jackson. The most objective accounts of the fight lay the blame on Reggie’s failure to come to terms with the clubhouse cliques that had sprung up racially. Billy North was part of a group of African American players who did not mix as easily with the white players as Reggie did. Reggie had grown up in a white neighborhood in Philadelphia and is said by Dayn Perry in his biography of Jackson to have been boasting of dating a “gorgeous white chick,” when North asked if she might have a friend for him.13

With racially loaded language that Mike Epstein claimed was all too common for Reggie Jackson, the slugger told North that the woman did not date African Americans, though he chose his words less carefully. North was quick and got the better of the larger man with surprising force. Jackson was injured in the fight, as was Ray Fosse, who tried to break it up. Fosse ended up in the hospital, Jackson merely missed a few innings, but according to Perry’s accounts, the aftermath of the fight bothered Reggie for weeks and hindered his performance on the field.

Ironically, Charlie Finley was always quick to try to bring the feuding parties together, as he did with North and Jackson. Whether Finley was an underlying irritant who kept the pot boiling or not, he went to considerable lengths to keep his star slugger happy. He held a “Reggie Jackson Day” several weeks after the fight with North and showered Jackson with gifts. However, the effects of the confrontation became cumulative and the expanding reservoir of ill will may have ultimately led to Jackson’s leaving Oakland. For all of the camaraderie that Jackson enjoyed playing in Oakland, the clubhouse animus that built up over the years from the “Junk Yard Dogs” lingered in his final years with the team.

The next fight, between Blue Moon Odom and Rollie Fingers, also took a toll. “Odom walked with a limp and Fingers needed six stiches in his scalp.”14 Jackson saw the fights as building a combative spirit that ultimately helped the team win its final World Series triumph against the Los Angeles Dodgers in 1974. Though they won the Series, the team began to come apart in the offseason that followed.

Reggie Jackson painted a sanguine face on the inner turmoil of the team and said it helped nurture the players’ winning ways. Others saw something darker, and ultimately Charlie Finley may have been moved by more than the money demands of his star-filled lineup to let them go. Mike Epstein believed he was traded at the end of the 1972 season because of the bad blood with Reggie Jackson. That fissure healed easily enough, but Finley’s inability to resolve the endless disputes between himself and his cast of All-Stars, and those between the players themselves may have provided additional motivation when he let the Yankees sign Catfish Hunter in 1975 and then traded Reggie Jackson and Ken Holtzman to the Orioles for the 1976 season. There may have been a precarious chemistry that fueled the fighting Athletics, but the same pugnacious character that marked relationships between so many involved with the team may have ultimately helped undermine their staying power as a team.

TED LEAVENGOOD is a SABR member and the author of three books, including Ted Williams and the 1969 Senators, and Clark Griffith, the Old Fox of Washington Baseball. He is Managing Editor and regular contributor to the historical baseball website, Seamheads.com and has been a frequent contributor elsewhere, including MASN Sports. Before retirement he worked as an urban planner for the U.S. Dept. of Housing and Urban Development, Fairfax County, Virginia, and the City of Atlanta. He lives in Chevy Chase, Maryland, with his wife.

Sources

Telephone interviews with Mike Epstein, June 15, 2007, and September 4, 2013.

Jackson, Reggie, with Kevin Baker, Becoming Mr. October (New York: Doubleday, 2013).

Jackson, Reggie, and Mike Lupica, Reggie: The Autobiography (New York: Villard, 1984).

Perry, Dayn, Reggie Jackson. (New York: Harper Collins, 2010).

The Sporting News, 1966-1974.

Notes

1 Reggie Jackson and Mike Lupica, Reggie, the Autobiography, 78.

2 Jackson and Lupica, 72.

3 Dayn Perry, Reggie Jackson, 317.

4 Perry, 51-52.

5 Wells Twombly, The Sporting News, October 27, 1973, 14.

6 Perry, 84.

7 Epstein interview.

8 Perry 86.

9 Perry, 86-87.

10 Jackson with Baker, 23,

11 Lupica, 83.

12 Ibid.

13 Perry, 122.

14 Jackson with Baker, 23.