The Chicago Cubs in Wartime

This article was written by Thomas Ayers

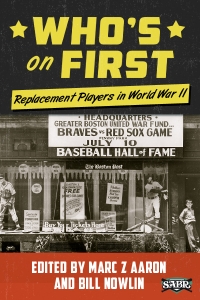

This article was published in Essays from Who’s on First: Replacement Players in World War II (2015)

The Chicago Cubs finished 1941 in sixth place in the National League with a 70-84 record. Their offensive attack was led by Stan Hack, who hit .317 with a .417 on-base percentage; Bill Nicholson, who contributed 26 homers and 98 runs batted in; and Babe Dahlgren, who added 16 homers in 99 games. The staff workhorse was Claude Passeau, who had 20 complete games in 30 starts, while 23-year-old Vern Olsen led the starting rotation with a 3.15 ERA. After spending most of the 1930s with the National League’s best or second-best attendance, in 1941 the Cubs finished fifth in the National League, drawing a crowd of 545,159.

There was limited immediate effect upon the Cubs when the United States declared war on Japan after the attack on Pearl Harbor. The team maintained largely the same lineup in 1942. The few lineup changes, which included Jimmie Foxx replacing Dahlgren at first base, occurred primarily for baseball reasons. The Cubs won two fewer games (68) in 1942 and Passeau, who posted a 19-14 record, was the only regular member of the pitching staff to compile a winning record. Hack and Nicholson again led Chicago’s offensive attack. Three years later, the Cubs were in the World Series.

It appears that the first member of the club to join the military was Russ Meers, who made his major-league debut for the Cubs on the last day of the 1941 season. In June 1942 he quit the Milwaukee Brewers of the American Association and joined the US Navy. Meers was assigned to the Great Lakes Naval Training Center, where he played baseball for manager Mickey Cochrane.

The Cubs began losing more players to military service in the 1942-43 offseason. Chicago had concluded the 1942 season with a doubleheader loss to the St. Louis Cardinals on September 27. The next day outfielder Marv Rickert, who hit .269 in eight games for Chicago that month, was inducted into the US Coast Guard.

A month later, on October 29, 1942, the Cubs lost Lou Stringer, who joined the Army Air Force, which assigned him to Williams Field in Arizona. Stringer was Chicago’s regular second baseman in 1942, hitting .236 in 121 games. The previous season Stringer accumulated the third-most at-bats on the club behind Hack and Nicholson.

Bobby Sturgeon and reliever Emil Kush both enlisted in the US Navy during the offseason. Sturgeon had hit .247 in 63 games as a backup middle infielder in 1942 after being displaced as the starting shortstop by Lennie Merullo.

The Cubs lost at least three more players in early 1943. Catcher Marv Felderman, whose brief major-league career consisted of three games in 1942, entered the Navy and third baseman Cy Block, a September call-up in 1942, joined the Coast Guard in April. First baseman Eddie Waitkus, who spent 1942 with the Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League after appearing in 12 games for the Cubs in 1941, was drafted into the Army shortly after receiving an invitation to spring training with the Cubs. Waitkus would be shot by a fan in 1949, an incident that served as the inspiration for Bernard Malamud’s novel The Natural.

Chicago posted a 6½-game improvement in 1943 with a 74-79 record. Bill Nicholson led the offense once again, as he had the previous two seasons. He had one of the best seasons of his career and finished third in National League MVP voting. Nicholson led the senior circuit in home runs (29) and runs batted in (128). Meanwhile, Passeau and Hiram Bithorn, who was the first Puerto Rican to pitch in the major leagues, anchored the staff with ERAs of 2.91 and 2.60, respectively. The pair combined for a 33-24 record with 37 complete games in 61 starts. The Cubs finished second in the National League in attendance, despite drawing only 508,247 fans, which was a reflection of the impact the war had on attendance across baseball.

As it did with all major-league baseball clubs, the gradual exodus of players to military service created opportunities for replacement players during the wartime years. Several players were given an opportunity to play major-league baseball that they may not otherwise have received. Two such players were Billy Holm and Walter Signer. Holm was a catcher who would play in the minor leagues for 18 years. Starting in 1943, Holm spent two years with the Cubs, appearing in 54 games as the club’s primary backup catcher in 1944, and hitting only .136 in 155 plate appearances. He played for the Boston Red Sox in 1945. Signer, a pitcher, returned to professional baseball in 1943 after having retired from the minor leagues in 1937. He made four appearances for the Cubs in 1943 and six in 1945, posting a 3.00 ERA in 33 innings.

Also among the Cubs who played as a result of the thinning of the ranks was outfielder Ed Sauer, who made his major-league debut in 1943 and hit .253 for the Cubs between 1943 and 1945. Sauer was reassigned to the minors in 1946, but returned to the majors in 1949 with the Boston Braves and St. Louis Cardinals.

Bill Schuster, who had nine major-league at-bats in 1937 and 1939, returned to the majors with the Cubs in 1943 and amassed 277 plate appearances between 1943 and 1945. In 1943 he hit .294 in 13 games. After hitting .191 in 1945, and scoring the winning run in Game Six of the 1945 World Series, Schuster never played in the majors again, although he played in the Pacific Coast League through the 1952 season.

Ed Hanyzewski, who was signed by the Cubs in 1941 after his freshman season at Notre Dame, made his major-league debut in 1942 as a 21-year-old. After six major-league appearances that year, Hanyzewski had his most successful season in 1943, when he posted a 2.56 ERA in 16 starts and 17 relief appearances. Hanyzewski was rejected for military service on medical grounds because of a knee injury he suffered playing high-school football. After missing two months in 1944 because of arm problems, Hanyzewski was rejected by the Army a second time that offseason. Hanyzewski threw just 4⅔ innings for the Cubs in 1945, primarily because of arm soreness following a “pop” he heard in his elbow during an appearance in August 1944. He was left off the Cubs’ World Series roster and threw just six more major-league innings.

Southpaw John Burrows posted a 5.05 ERA for the Cubs in 35⅔ innings in 1943 and 1944. Third baseman Pete Elko was another player who only saw major-league action during the war, as he went a combined 9-for-52 for the Cubs in 1943 and 1944. Neither Burrows nor Elko played in the majors after the 1944 season.

The exodus continued after the 1943 season, robbing the Cubs of one of their rotation anchors. Although he was born in Puerto Rico, Hiram Bithorn was a US citizen and eligible for the draft, pursuant to the 1917 Jones Act. His request for a draft deferral was denied and he was inducted into the Navy on November 26, 1943. Bithorn spent two years serving at San Juan Naval Air Station in Puerto Rico.

In April 1944 the Cubs lost Peanuts Lowrey, who played in 130 games the previous season. Lowrey had hit .292 and finished second in the National League with 13 stolen bases and tied for third with 12 triples. The Army assigned Lowrey to Fort Custer, Michigan, where he was the player-manager of the baseball team at the Military Police Officers Candidate School. Lowrey received a medical discharge on October 13 because of “weak knees.”

Lowrey wasn’t the only Cubs player granted an early medical discharge from the Army. Mickey Livingston, who had played in 36 games for the Cubs in 1943, was drafted into the Army in March 1944. Reportedly, the pressure from his helmet caused him to suffer severe headaches and created a significant vision problem. He was granted a medical discharge that November and, like Lowrey, returned to play for the Cubs in 1945.

The Cubs also lost the services of Charlie Gilbert and Al Glossop, who were both drafted into the Navy. Gilbert was stationed at the Naval Air Technical Training Center in Norman, Oklahoma. Glossop, who was acquired from the Phillies in September 1943 but hadn’t yet played for the Cubs, entered the military on March 17, 1944, and spent that year stationed at the Great Lakes Naval Training Center.

The 1944 season did not start promisingly for the Cubs. Without Bithorn, the rotation didn’t have the depth of the previous season and the club started with only one victory in its first 10 games. Manager Jimmie Wilson was fired and Charlie Grimm succeeded him. The Cubs showed improvement under Grimm, as they posted a winning record under his stewardship and finished 1944 with a 75-79 record overall.

Nicholson led the National League in home runs (33) and runs batted in (122) for the second consecutive year. He also led the NL with 116 runs scored and 317 total bases. He finished second in MVP award voting to Marty Marion, the shortstop for the St. Louis Cardinals. Passeau continued as the staff’s ace with a 15-9 record and 2.89 ERA in 27 starts, but behind him and Hank Wyse, who had an unexpectedly strong year, the back end of the rotation spent most of the year in flux.

Several wartime replacement players also debuted for the 1944 Cubs. Southpaw Hank Miklos made his major-league debut on April 23, 1944, throwing five innings in a blowout loss to the Cardinals. In his second and last major-league appearance, the 33-year-old Miklos threw another two innings in a blowout loss to Brooklyn on May 15. Aside from those two appearances, there is no record of Miklos playing in Organized Baseball after 1939, which he spent pitching for the Winnipeg Maroons of the Class-D Northern League.

Pitching exclusively out of the bullpen, aside from one spot start, Mack Stewart debuted for the Cubs in 1944 and threw 40⅔ innings over the next two seasons. Charlie Gassaway, who was born in Gassaway, Tennessee, made his major-league debut in September 1944. He was hit hard in both of his starts for the Cubs. However, Gassaway wound up throwing more than 150 major-league innings over the next two seasons for the Philadelphia Athletics and Cleveland Indians.

Catcher Mickey Kreitner, who made his major-league debut in 1943 as a 20-year-old and went 3-for-8, received an extended look as a backup catcher in 1944. He spent the entire year in the majors, but hit only.153 with one RBI in 85 at-bats. Kreitner, whose minor-league career began in 1941, last played professional baseball in 1945 with the Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League.

Catcher Roy Easterwood made 34 plate appearances in 17 games in 1944, his only major-league season. He hit .212 with two doubles and a home run. The Texan would have a 15-year minor-league career, but never appeared in the major leagues again. However, he had a longer major-league career than Garth Mann. Mann, a pitcher who never got the chance to pitch in the major leagues, entered a game against the Brooklyn Dodgers on May 18 as a pinch-runner for Lou Novikoff in the eighth inning with the Cubs trailing 7-1. He scored Chicago’s second run and was replaced defensively in the top of the ninth inning. Chicago came back to win the game in the bottom of the ninth inning, 8-7, but Mann never appeared in the majors again.

The Cubs lost several more players during the late stages of the war. On October 2, 1944, Dale Alderson entered military service with the Navy, after previously having being rejected twice because of kidney ailments. He was assigned to the Naval Training Center in San Diego, where he served until he was discharged on October 19, 1945. On January 15, 1945, Bill Fleming, who had made 39 appearances for the Cubs in 1944, entered the Army and was stationed at Fort Lewis, Washington.

In 1945 the Cubs lost the talents of Dom Dallessandro, who had his best season for the Cubs in 1944, when he hit .304 and drove in 74 runs. He entered the Army on March 8, 1945, and was assigned to Fort Lewis. Dallessandro, who along with Bithorn was perhaps the most noticeable loss for the Cubs during the war, was placed in charge of the gymnasium at Fort Lewis. Both Fleming and Dallessandro played for the camp’s baseball team, alongside a number of fellow major leaguers, including Danny Litwhiler of the Cardinals, Cincinnati’s Ray Mueller and Frankie Kelleher, and Ron Northey of the Phillies. With such a talented roster, it was not surprising that the baseball team was extremely successful. The club had a 37-game winning streak and won the Ninth Service Command championship. Dallessandro was discharged on April 2, 1946, and appears to have been the last Cubs player discharged from military service after the war.1

Like Fleming and Dallessandro, many of the Cubs played baseball while they served in the military. Among the many players who stayed involved in baseball was Hi Bithorn, who was the player-manager of the baseball team at the San Juan Naval Air Station. Emil Kush pitched for the Lambert Field Navy Wings during the war and defeated the Cincinnati Reds and the Dodgers in exhibition games. Bobby Sturgeon played while stationed in the Navy and, along with Joe DiMaggio, played for a service all-star team that played in several benefit games around California in 1943. Lou Stringer starred for the Williams Field Flyers, who won the Arizona Servicemen’s League in 1943 and 1945, amassing a 41-9 record during their first championship season.

Eddie Waitkus and Marv Rickert likely had the most demanding and dangerous duties of all Cubs players during the wartime. Waitkus’s military service began with the Army engineer amphibian command at Camp Edwards in Massachusetts. In 1944, he was assigned to the 544th Engineer Boat & Shore Regiment, 4th Engineer Special Brigade. He spent much of his time in the Pacific Theater, where he was stationed at Bougainville, New Guinea. In September 1944 Waitkus participated in amphibious landings at Marotai in the Dutch East Indies and then in another series of amphibious landings in January 1945 at Lingayen in the Philippines.

However, Rickert, who was in the Coast Guard, may have faced more danger than any other Cub. He worked aboard an explosives boat in the Pacific Theater, transporting ammunition from Seattle to American bases in the Aleutian Islands, an area reportedly high on the list of Japanese targets. During his last two years in the Coast Guard he was stationed in Seattle and he coached the Coast Guard’s baseball team, which posted a 98-8 record during that period.

Meanwhile, in the major leagues, the Cubs continued their turnaround under Charlie Grimm in an even more dramatic fashion in 1945. The Cubs (98-56) won the National League pennant with a 98-56 record. The team was particularly impressive in the second half of the season, posting a 54-27 record. Chicago played outstanding baseball in July, compiling a 26-6 record on the strength of an 11-game winning streak that began on July 1. During this streak, the Cubs took first place in the National League from Brooklyn, a lead they would never relinquish. The club nearly doubled its attendance from 1943, drawing 1,036,386 fans to Wrigley Field, which placed them second in the National League.

The Cubs finished the season with a 22-10 record in September and won the pennant by three games over the St. Louis Cardinals. The Cubs finished with at least a .500 record against every National League club but the Cardinals, against whom they won only six of 22 contests. The Cubs went 3-5 against the Cardinals in September, but midseason acquisition Hank Borowy won all three of his starts against St. Louis, which proved to be the difference in the standings. The Cubs also owed much of their pennant title to their play against the Cincinnati Reds, against whom they won 21 of 22 games.

The 1945 Cubs won 23 more games than they did in 1944. Their success in 1945 appears to stem from a combination of roster volatility as a result of World War II service and a number of players having career seasons.

The Cubs weren’t the only club to experience a big jump in the standings between seasons during the war. While the Cubs went from fourth place in 1944 to winning the pennant in 1945, Brooklyn also improved by four places in the standings from seventh place to third. Cincinnati dropped from third place in 1944 to seventh in 1945 and in the American League the Washington Senators improved from eighth place to second place. As a further demonstration of wartime unpredictability, between 1942 and 1943 in the American League, Boston dropped from second place to seventh and Washington rose from seventh to second.

It’s also worth noting that the 1944 Cubs outscored their opponents by 32 runs, which might have made them a little unlikely to finish with a record under .500. In 1945 the Cubs had a much better season and outscored their opponents by over 200 runs. Several players buoyed the offense with career years, which more than compensated for Nicholson having the poorest season of his career to date. Andy Pafko, who had struggled at the plate in 1944, which was his first season as a regular, burst onto the scene in 1945 and finished fourth in MVP voting. The 24-year-old outfielder reached double digits in doubles, triples, and home runs. He had a career-high 110 RBIs and hit 12 triples after hitting two the previous season.

Stan Hack didn’t have his best offensive season in 1945, but he had his best season in several years with a .323 batting average and 29 doubles. He finished 11th in MVP voting and posted an on-base percentage and slugging percentage more than 50 points higher than he had the previous season. Hack retired after the 1947 season at the age of 37.

Don Johnson made an unexpected offensive contribution as the Cubs’ second baseman. The Chicago native was another wartime replacement player who made his debut in 1943 as a 31-year-old rookie. He had his best offensive season in 1945, setting career highs in batting average, on-base percentage, and slugging percentage. Johnson also showed marked improvement in the field, cutting his error total from 47 in 1944 to 19 in 1945. Perhaps a reflection of how unexpected his performance was came when Johnson finished 21st in MVP voting that season.

However, the key to the offense in 1945 was first baseman Phil Cavarretta, who won the National League MVP award with a .355 batting average, 34 doubles, and 97 runs batted in. He posted a .449 on-base percentage after earning 81 walks and he struck out only 34 times. Cavarretta, who was an All-Star in 1944, 1946, and 1947, made his debut in 1934, but hadn’t had more than 350 at-bats in a season between 1937 and 1941 and only became a regular after World War II began. Cavarretta had never hit over .300 or posted a slugging percentage over .425 until the 1944 season, when he came into his own as an offensive force while playing regularly.

While the offense improved from the 1944 season, it was the club’s pitching staff that really stood out. The Cubs allowed only 533 runs, which was the least in the National League by 49 runs. The Cardinals finished with the second-fewest runs allowed with 582 and the Pirates finished with the third-fewest runs allowed in the National League after allowing 681 runs, Chicago led the National League in ERA and complete games and finished with the fewest hits, runs, home runs, and walks allowed. All eight pitchers who pitched over 50 innings for the club posted ERAs of 3.50 or lower.

Claude Passeau had his last good full season in the majors, posting a 2.46 ERA in 27 starts. He went 17-9 with 19 complete games and a National League-leading five shutouts. He allowed only four home runs in 227 innings. Passeau was out of baseball after the 1947 season

In 1945 the staff workhorse was Hank Wyse, who won 22 games and lost 10. He threw 278⅓ innings with a 2.68 ERA and finished with 23 complete games in 34 starts. He posted an identical ERA in 1946, but his record dropped to 14-12. Wyse never had a winning record again. After not pitching in the majors in 1948 and 1949, he resurfaced and spent a full season with the Athletics in 1950. He pitched briefly for the Athletics and Senators in 1951 and then never pitched again in the major leagues.

A pair of 38-year-old Cubs veterans combined for 29 wins. Kentucky native Paul “Duke” Derringer’s went 16-11 in 30 starts and five relief appearances with a 3.45 ERA in his last season in the major leagues. Had the save been an official statistic in 1945, Derringer would have earned a save in four of his five relief appearances. Although he was the only member of the rotation with an ERA over 3.00, Derringer’s ERA was still 0.70 lower than it was in 1944, when he only won seven games.

However, the most unexpected performance on the entire roster probably came from Ray Prim. Prim hadn’t pitched in the majors since 1935, aside from 60 innings in 1943. The southpaw spent 1944 in the Pacific Coast League and was out of the major leagues after 23⅓ innings in 1946. However, he was a major contributor for the Cubs in 1945 with a 13-8 record with a 2.40 ERA in 165⅓ innings. He led the National League in ERA, WHIP, and strikeout-to-walk ratio and allowed the fewest hits and walks per nine innings pitched.

The final piece of the puzzle was the midseason acquisition of Hank Borowy. The Cubs purchased Borowy from the New York Yankees on July 27 for $97,000. At that point in his career Borowy had compiled a 56-30 record and a 2.74 ERA. With the Cubs, Borowy went 11-2 in 14 starts with 11 complete games. He made one relief appearance, in which he would have earned a save. For his accomplishments, Borowy finished sixth in National League MVP Award voting and earned The Sporting News National League Pitcher of the Year award. Borowy went 25-32 over the next three years and the Cubs dealt him to the Phillies after the 1948 season.

Three other pitchers who made spot starts when necessary prior to the acquisition of Borowy also pitched well. Bob Chipman, whom the Cubs had acquired for Eddie Stanky in mid-1944 from Brooklyn, pitched mostly out of the bullpen, but he also made 10 starts and posted a 3.50 ERA in 72 innings. Hy Vandenberg, who was out of the majors from 1941 through 1943, put up a 3.49 ERA in 95⅓ innings as a 39-year-old. He went 7-3 in seven starts and 23 relief appearances and never pitched in the majors again after that season. Illinois native Paul Erickson posted a 3.32 ERA in 108⅓ innings in nine starts and 19 relief appearances. Erickson, who made his debut in 1941, was out of baseball after the 1948 season.

Another player who was given an unexpected chance to play in the major leagues again was 43-year-old outfielder Johnny Moore. Moore, who broke in with the Cubs in 1928, hadn’t made a major-league appearance since 1937, but he returned to the majors in his 21st season in professional baseball. In his limited opportunity, Moore went 1-for-6 with two runs batted in.

Catcher Paul Gillespie hit .283 with a .405 slugging percentage in 89 games for the Cubs during the war years. Most of Gillespie’s playing time came in 1945, when he played in 75 games and hit .288. He had three homers and 25 RBIs and walked 18 times with only nine strikeouts. Outfielder Lloyd Christopher made his major-league debut that season for the Boston Red Sox. He was selected off waivers by the Cubs on May 26. He only played in one game for the club and didn’t record an at-bat. Also, George Hennessey, who pitched briefly in the majors in 1937 and 1942, threw 3⅔ innings for the Cubs in 1945.

The Cubs advanced to the World Series for the first time since 1938 and faced the Detroit Tigers. The first game of the World Series was at Briggs Stadium and the Cubs won 9-0 behind a six-hit shutout by Borowy. After Chicago lost the second game, Passeau threw what was likely the best game of his life in Game Three. He allowed only one hit, a second-inning single by Rudy York, and faced only one batter over the minimum as the Cubs won, 3-0.

The Tigers won the next two games in Chicago to take a 3-games-to-2 lead in the Series. Billy Goat Tavern owner Billy Sianis and his pet goat were asked to leave Wrigley Field during the fourth game, leading to the alleged Curse of the Billy Goat. Facing elimination, the Cubs took a 7-3 lead in Game Six. However, the Tigers clawed back to tie the game in the top of the eighth inning, but the Cubs prevailed in the bottom of the 12th, inning, 8-7, on a double by Stan Hack with two outs, scoring pinch-runner “Broadway Bill” Schuster from first base.

Unfortunately for the Cubs, the Tigers jumped all over Borowy in Game Seven. Borowy had pitched four innings of relief in Game Six two days earlier and, perhaps still tired from that appearance, allowed three of the five runs the Tigers scored in the top of the first. Detroit wound up with a 9-3 victory and a World Series title.

The loss in the World Series didn’t occur because of a lack of contribution from at least two players who had returned from military service. Peanuts Lowrey played in all seven games and hit .310 and scored four runs. Mickey Livingston played even better, hitting .364 over six games with three doubles and four runs batted in.

However, the Cubs’ replacement players didn’t fare so well. Sauer batted twice in the World Series, striking out both times. Gillespie made three appearances and went 0-for-6. Meanwhile, Schuster only played in one game, but he made a key contribution, as previously noted, as he scored the winning run in the 12th inning of Game Six to send the World Series to a seventh game

The Cubs dropped to third place in the National League in 1946 with an 82-71 record. Cavarretta and Hack led the offense again, but didn’t live up to the previous season’s performance. Meanwhile, Nicholson slumped and was no longer a regular by season’s end. Also, the pitching rotation was not as deep behind Wyse and Johnny Schmitz, as Passeau only made 21 starts and struggled, while Borowy posted a winning record, but with a relatively high 3.76 ERA.

A number of the Cubs who had served in the war returned to the team for the 1946 season. Eddie Waitkus played 106 games, almost entirely at first base, Peanuts Lowrey played 144 games, mostly in the outfield, and Marv Rickert made 107 appearances in the outfield. Although they weren’t regulars, Bob Sturgeon and Lou Stringer played in 100 and 80 games, respectively. Mickey Livingston, Bob Scheffing (who missed three seasons while in the Navy), and Dom Dallessandro all played in more than 60 games. Also, Cy Block, Al Glossop, and Charlie Gilbert made brief appearances for the club. The pitching staff benefited less from the returning players. Of the players who served, only Emil Kush threw over 100 innings. Hi Bithorn, Bill Fleming, Russ Meyer and Russ Meers all pitched far fewer innings.

As of the date of publication, this was the last time the Cubs appeared in the World Series.

THOMAS AYERS is a lawyer who practices labour and employment law. He has earned degrees from the University of Toronto, the London School of Economics, and Queen’s University. Born and raised in Toronto, he is a lifelong Blue Jays fan, who has contributed several biographies to the SABR Baseball Biography Project.

Sources

Baseball in Wartime Website:

baseballinwartime.com/those_who_served/those_who_served_nl.htm

SABR Biographies:

- Berger, Ralph, “Russ Meyer”

- Bohn, Terry, “Ed Hanyzewski”

- Griffith, Nancy Snell, “Mickey Livingston”

- Gumbs, Gene, “Marv Rickert”

- Morrison, John, “Bobby Sturgeon”

- Nowlin, Bill, “Dom Dallessandro”

- Nowlin, Bill, “Lou Stringer”

- Quevedo, Jane Allen, “Hi Bithorn

- Rosen, Dick, “Peanuts Lowrey”

Other Sources Consulted:

Baseball Alamanac: baseball-almanac.com

Baseball-Reference: baseball-reference.com

Retrosheet: retrosheet.org

Notes

1 See: baseballinwartime.com/player_biographies/dallessandro_dom.htm.